One of the goals of the policy of the Duke of Florence (and from 1569 Grand Duke of Tuscany) Cosimo I de’ Medici, was to reassert the primacy of Florence at the cultural level as well. Cosimo I restarted from the Renaissance idea of art as a means of enhancing the prestige of a state: the numerous commissions given to artists are explained according to these intentions. These assignments included the decoration of city squares and palaces with the creation of sculptures. All the great Mannerist sculptors who worked in Florence in the sixteenth century and among whom, inevitably, great rivalries arose, were engaged in this regard.

The most heated rivalry was between Bartolomeo Brandini known as Baccio Bandinelli (Florence, 1488 - 1560) and Benvenuto Cellini (Florence, 1500 - 1571). The former artist lived almost his entire existence in an attempt to imitate Michelangelo, but met with numerous and bitter failures as his gigantism was excessively charged and exaggerated and lacked the philosophical foundations underlying Michelangelo’s art. His best-known work,Hercules and Cacus, which he finished in 1534 after a full nine years of work (he had been commissioned by the Medici to flank the David in Piazza della Signoria), received nothing but insults and mockery at its inauguration: famous is that of Benvenuto Cellini himself, who in his Vita calls the work “un saccaccio di poponi” (i.e., of melons) precisely because of the exaggerated accentuation of the muscles. What is more, the work also attracted the ridicule of the republicans: in fact, the David had been sculpted by Michelangelo, a staunch republican, andHercules and Cacus by Baccio Bandinelli (a work that still stands today in Piazza della Signoria), pro-Medicean and among the Medici’s greatest protégés, so the republicans could say that their party’s superiority in the field of art was guaranteed.

Although throughout his career he received commissions for large-scale works, paradoxically Baccio Bandinelli was better at small-scale sculptures, so much so that patrons often turned to him for colossal works, in view of the fact that his sketches were of the highest quality. However, his art remains limited by the vain and enduring attempt to imitate and try to surpass the achievements of Michelangelo’s art.

Benvenuto Cellini, too, started from Michelangelo’s schemes, to which, however, he was able to give, in comparison with his rival, a very notable elegance (as also appears to us in his most famous work, the Perseus that is in Florence in the Loggia dei Lanzi), which came to him from his training as a goldsmith and which many of the other Mannerist sculptors lacked, as they were too stuck in their attempt to refer to Michelangelo’s sculpture (a constraint that Cellini, on the other hand, showed he was able to overcome without problems). A craft, that of the goldsmith, which, alongside that of the sculptor, Benvenuto Cellini never abandoned throughout his career. Certainly the most passionate and �?heroic�? of the Mannerist sculptors, not least because he had a particularly violent and confrontational temperament (one recalls his famous quarrel with Baccio Bandinelli before Cosimo I), Benvenuto Cellini proposed a refined and free art that stood somewhere between Renaissance classicism and the extreme virtuosity of other Mannerist artists.

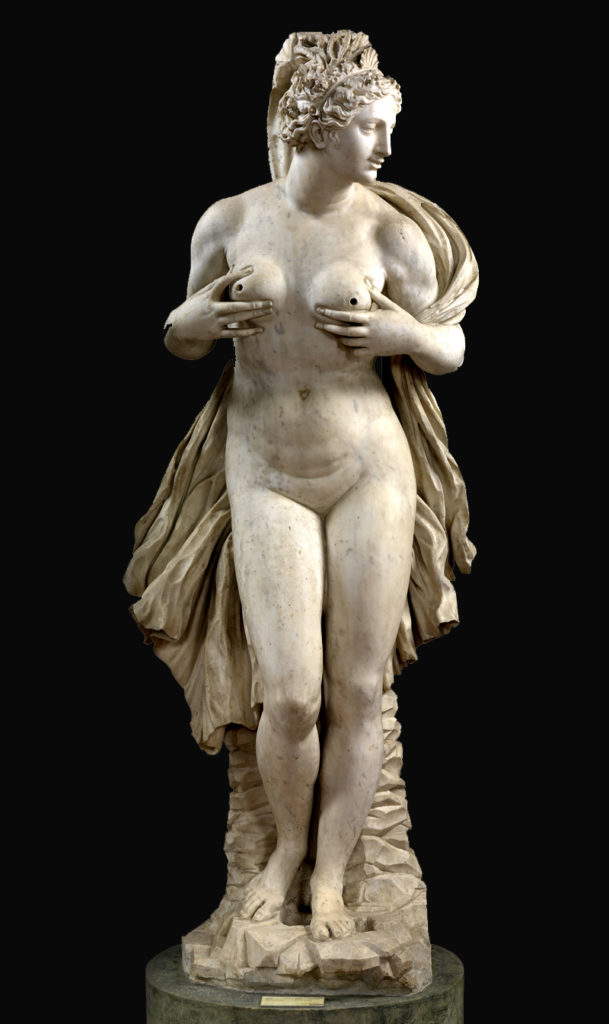

Another artist who replicated Michelangelo’s plasticism, but reworking it from an original point of view, was Bartolomeo Ammannati (Settignano, 1511 - Florence, 1592), who was a pupil of Baccio Bandinelli. In Bartolomeo Ammannati one begins to see a marked freedom of invention that finds fulfillment in the poses, original, of certain of his achievements, as well as a subtle sensuality that pervades many of the works with female subjects (particularly goddesses of classical antiquity, such as Ceres, 1556-1561, Florence, Bargello Museum). However, even Bartolomeo Ammannati did not fail to draw criticism for some of his works, such as the Fountain of Neptune, which, in return for attempting to imitate Michelangelo (though not as reckless and exaggerated as Baccio Bandinelli’s), only garnered mocking verses. Thus, Bartolomeo Ammannati’s greatness is to be found above all in the originality of certain of his inventions as well as in his ability to create compositions to spectacular effect (such as the Fountain of Sala Grande, which was reassembled for a few months in 2011 on the occasion of an exhibition on the sculptor at the Bargello Museum).

Of the same generation as Bartolomeo Ammannati was Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (Florence, 1507 - 1563), a collaborator of Michelangelo whose plastic vigor, like all Mannerist sculptors, he took up, which he was able to interpret often in heroic forms and above all connoted by a very high dramatic charge(Fountain of Orion, 1547-1551, Messina, Piazza Duomo).

The artist in whom thebizarre and virtuoso flair of Mannerism in sculpture found its zenith was probably Giambologna, the Italianized name of the Flemish sculptor Jean de Boulogne (Douai, 1529 - Florence, 1608). Following a sojourn in Rome around 1550, he became an adopted Italian and settled in Florence beginning in 1562, also becoming a protégé of the Medici family. An artist of a later generation than his predecessors, he was the sculptor who probably ended the Mannerist experience by anticipating the trends of Baroque sculpture.

Giambologna, too, started from Michelangelo’s gigantism, but reinterpreted it in exceptionally free forms characterized by virtuosity and irregularity, thus going beyond what Benvenuto Cellini had succeeded in doing despite not having the same degree of refinement as he did. Certain of his works, however, would not have existed without Cellini’s precedents, one example above all being the celebrated Mercury, 1580, Florence, Bargello Museum. It is Giambologna who is credited with creating the serpentine figure (i.e., the figure assuming an S-shaped movement) through a looser dynamism than that of his contemporaries-a way of proceeding that also achieved notable echoes in the Baroque period.

Another artist belonging to the same generation as Giambologna, namely Vincenzo Danti (Perugia, 1530 - 1576), was also active in Florence. An artist capable of making figures as tortuous as those of Giambologna, but also capable of solemnly celebratory monuments with a classicist taste, he was one of the few Mannerist sculptors to reflect on the Roman Michelangelo and thus on the most emotionally powerful works of the Caprese artist. An example of this passionate study is one of Vincenzo Danti’s masterpieces, the Beheading of the Baptist (1571, Florence, Museo del Duomo) executed in the last years of his career for the Florence Baptistery.

Among the most ingenious sculptors of Mannerism can also be counted Niccolò Pericoli known as Il Tribolo (Florence, c. 1500 - 1550): an author distinguished by a high sense of decorativism. In his sculptures he diluted Michelangelo’s gigantism in milder forms, but he is remembered above all as a garden architect. Indeed, he oversaw the arrangement of numerous gardens in the Medici villas (he is credited with the rearrangement of the Boboli gardens), decorating them with fountains that also revealed his skill in hydraulic works(Fountain of Hercules, after 1536, Florence, Medici Villa of Castello).

|

| Mannerist sculpture in Florence. Origins, developments, artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.