Kinetic and programmed art. History, style, artists

Beginning in the 1950s in Europe, people began to talk about “Kinetic Art,” an artistic current that put a series of more or less complex technological apparatuses at its service. Also known as "Programmed Art," this trend aimed to convey to the public a perception of movement, whether real or illusory. The moment this expressive language began to play with optical effects, spreading across the United States, it began to be called Optical Art. Specifically, kinetics is the science that studies the motion of bodies in relation to their structure.The art that spread in Europe at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s applied the study of kinetics, expressing a strong interest in the many scientific innovations that were accumulating around the middle of the twentieth century.

Artists worked to move beyond the static nature of the work of art, and works were produced that presented dynamic mechanisms, aiming to create movement, discovering in the phenomenal world an ever-changing reality. As the noted art critic Lea Vergine had to say in 1973, kinetic art represented “the renewal of contemporary aesthetic making,” and tended “toward the identification of new values through the analysis of perceptual phenomena.” A central point among the goals pursued was theactive interaction between art and viewer: again Lea Vergine wrote that “the authors design models that intend to perform a social function - demythicization - and a cognitive one - placing the public in a perceptive situation and, therefore, of awareness.” Kinetic art was consecrated with the Le Mouvement exhibition in Paris in 1955, at the Denise René Gallery; its downward parabola began in the late 1960s, overshadowed by the colors of Pop Art and the forms of Arte Povera.

Origins and Development of Kinetic Art.

Mid-twentieth-century Europe experienced a technological revolution that profoundly changed the way of human life.Nuclear power led to the idea that inexhaustible reserves of energy could be had; increasingly efficient and faster aircraft and means of transportation were being designed. Thespace age was racking up more and more successes, beginning with the launch of the first Sputnik into orbit in 1957. Overwhelmed by this technological frenzy, the arts world responded to the stimuli by opening up to science, embracing technology and industrial production processes. When enough mechanical energy was introduced into the work of art to induce movement, whether real or virtual, it was called kineticism. The cultural context that enabled the initiation of this type of artistic research can be traced to a specific moment in twentieth-century art history.

Kinetic Art defined its form in a rather fluid circumstance, developing within the Neoavantgarde investigations of the 1960s and 1970s, the same ones in which Arte Povera and Minimalism also moved. They were artistic investigations that were particularly attentive to modes of operation, because of the introduction of the use of new artistic techniques and also because of an active interaction between the most diverse disciplines. These expressions were also characterized by a generalized rejection of the commercial system, by the direction toward a direct relationship between artistic behavior and everyday existence. The forerunner of this way of understanding art making was Marcel Duchamp (Blainville-Crevon, 1887 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1968), an artist who enacted a revolution in the cultural field, giving impetus to the birth of Dadaism and Surrealism, but above all to Conceptual Art, which was decisive in the development of later art, in that it forged a new behavior in art, putting it at the service of the idea.

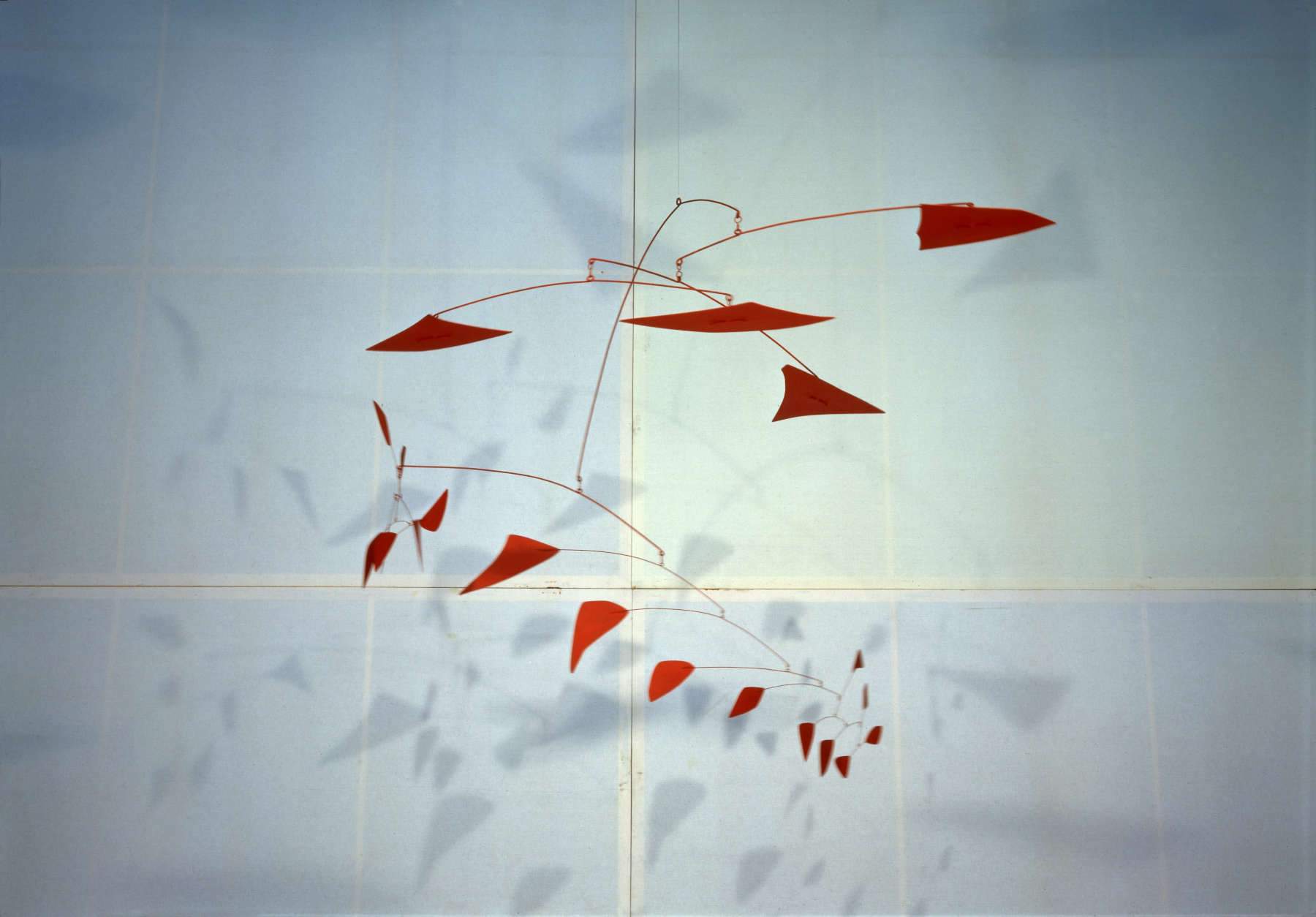

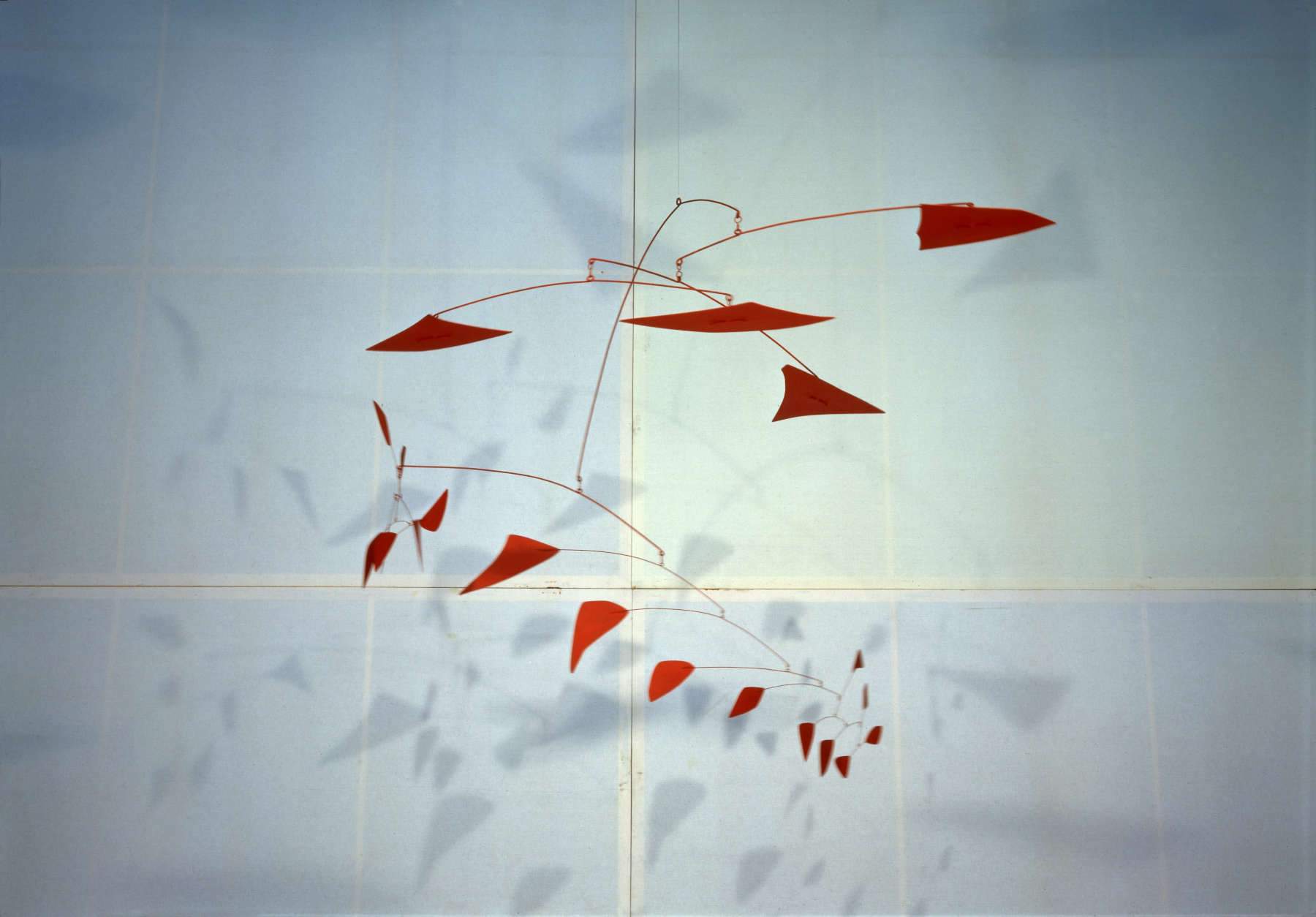

In Kinetic Art, the fundamental principle was to place movement as its own ontological condition. The search for and perception of movement was what most fascinated the artists of Kineticism. The results of this early research were presented in 1955 at the Denise René Gallery in Paris: the exhibition Le Mouvement definitively opened the season of Kinetic Art, presenting the works of already established artists such as Duchamp and Alexander Calder (Lawnton, 1898 - New York, 1976), along with those of more younger artists such as Yaacov Agam (Rishon LeZion, 1928), Pol Bury (La Louvière, 1922 - Paris, 2005), Jesús Raphael Soto (Ciudad Bolívar, 1923 - Paris, 2005), and Jean Tinguely (Freiburg, 1925 - Bern, 1991).

Dynamism was the theme addressed in relation to its links with technology and scientific and industrial progress. Technological devices such as photography and the movie camera were used in this regard; the photographic lens allowed for the analysis of captured movement as it unfolded. The philosopher Walter Benjamin, in his The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility, spoke of movement and how the new means, the movie camera and its auxiliaries, allowed for a better understanding of it: “With the close-up you dilate space, with the slow-motion the movement. And just as in magnification it is not so much a matter of a mere clarification of what is nevertheless seen indistinctly, but, rather, entirely new structural formations of matter come to light, so the slow motion brings to light not only known motifs of movement, but in these motifs it discovers entirely unknown ones” (1935). Other disciplines that gave value to movement in its most artistic sense was certainly theater and, undoubtedly, ballet.

In this new way of looking at art, based on perception, thought and idea, the figure of the artist also came to be endowed witha philosophical aura, the one proper to directors and composers, since what mattered at that time was the ability to design, to conduct an aesthetic reflection that was original. For this reason, at that time in the art world a very active role was attributed to critics and curators, who became mediators between artists and users, such as the French Pierre Restany and the Italian Germano Celant, who coined the definition of “Arte Povera” in 1952.

In Italy, Bruno Munari (Milan, 1907 - Milan, 1998) was one of the great protagonists of Kinetic Art. In 1952 he wrote Il manifesto del macchinismo, a text in which he denounced man’s dependence on the machine, to which he was essentially a slave. He therefore suggested that artists break out of that sterile position and give a new function to the machine, transposing it into the artistic context. Again according to Munari, artists “are the only ones who can save humanity from this danger.” These were the ideas circulating in the Peninsula in the middle of the century.

In 1959, artists Giovanni Anceschi (Milan, 1939), Davide Boriani (Milan, 1936), Gianni Colombo (Milan, 1937 - Melzo, 1993), Gabriele de Vecchi (Milan, 1938 - Milan, 2011) and - at a later stage - Grazia Varisco (Milan, 1937) formed Gruppo T in Milan. Although they presented themselves as a collective, a certain emphasis on personal production was never denied. The group carried out perceptual experiments, investigated the concept of habitability of the work by understanding it as an environment; the spaces were always open to the emotional involvement of the viewers. The group adopted the term Miriorama (from the Greek for “infinite visions”) to define its artistic agenda and to give a title to its fourteen exhibitions, the first of which was held at the Pater Gallery in Milan from January 15 to 18, 1960: this was an event in which four experiments were presented: Painting in Smoke, Decorative Oxidations, Burning Surface, Large Pneumatic Object. Group T focused on the idea of the changing image, on the temporal sequence: the poetic statement of the event read that “every aspect of reality, color, form, light geometric spaces and astronomical time, is the different aspect of the giving of space-time or rather: different ways of perceiving the relationship between space and time. We therefore consider reality as a continuous becoming of phenomena that we perceive in variation.”

Padua, too, was the scene of a fundamental junction in the path of Kinetic Art: in 1960 Gruppo N was born : Alberto Biasi (Padua, 1937), Ennio Chiggio (Naples, 1938 - Padua, 2020), Edoardo Landi (San Felice sul Panaro, 1937) and Manfredo Massironi (Padua, 1937 - Padua, 2011). Compared to the Milanese group, Group N operated in the full spirit of the collective, signing individual works with the group’s name, totally sacrificing individuality (unlike Group T, where some of the Miriorama exhibitions were personal): in the poetic statement presented in 1961 it was explicitly said that “the wording enne distinguishes a group of ’experimental draftsmen’ united by the need to research collectively.” Together, the two groups were precursors and premises for the birth of Programmed Art: in 1962, Bruno Munari organized an exhibition at the Olivetti store together with philosopher Umberto Eco, who coined the term " ProgrammedArt." It referred to the possibility of technical or electronic programming of the work by the artist. Such programming was necessarily tied to the receptive presence of the visitor, who was not limited to the mere position of observer of images, but became co-author of the work itself, taking part in it. This was what happened in 1967 in a work such as Spazio Elastico by Gianni Colombo (Gruppo T) where the viewer became part of the artistic environment, completely enveloped and a fundamental part of the space.

The exhibition Arte programmata had the merit of launching the kinetic artists into the international art scene, leading them to the various editions of the Venice Biennale (1964 and 1968) and to the IV San Marino Biennale “Oltre l’Informale” (1963), where the jury led by Giulio Carlo Argan awarded equal prizes to the collectives Gruppo N of Padua and Gruppo Zero of Düsseldorf. The peak of Kinetism’s success also corresponded to its descent, accompanied by doubts and questions about what the boundaries of making and being art were. In the catalog of the exhibition Programmed Art, Umberto Eco wrote, “It is not painting, it is not sculpture, but is it at least art? Mind you, the question here is not whether it is ’great art,’ but whether such an operation falls roughly into the category of art. [...] I don’t really know how he did it, but it was always art, first, that changed our way of thinking, of seeing, of feeling, even before, sometimes a hundred years before, we could understand what the need was.” In 2012, the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome celebrated Kinetic and Programmed Art by dedicating the space of an exhibition to it, reflecting a rediscovery and a recent, renewed interest.

The major exponents of Kinetic Art: styles and trends

Artists directed their research on the movement by implementing a new collaboration, a synthesis of art and science that defeated the anachronistic figure of the romantic artist averse to progress. What was emerging was a new figure, that of a creator who could use the novelties introduced by science, rereading them in a creative sense and using them to expand his or her own expressive capabilities.

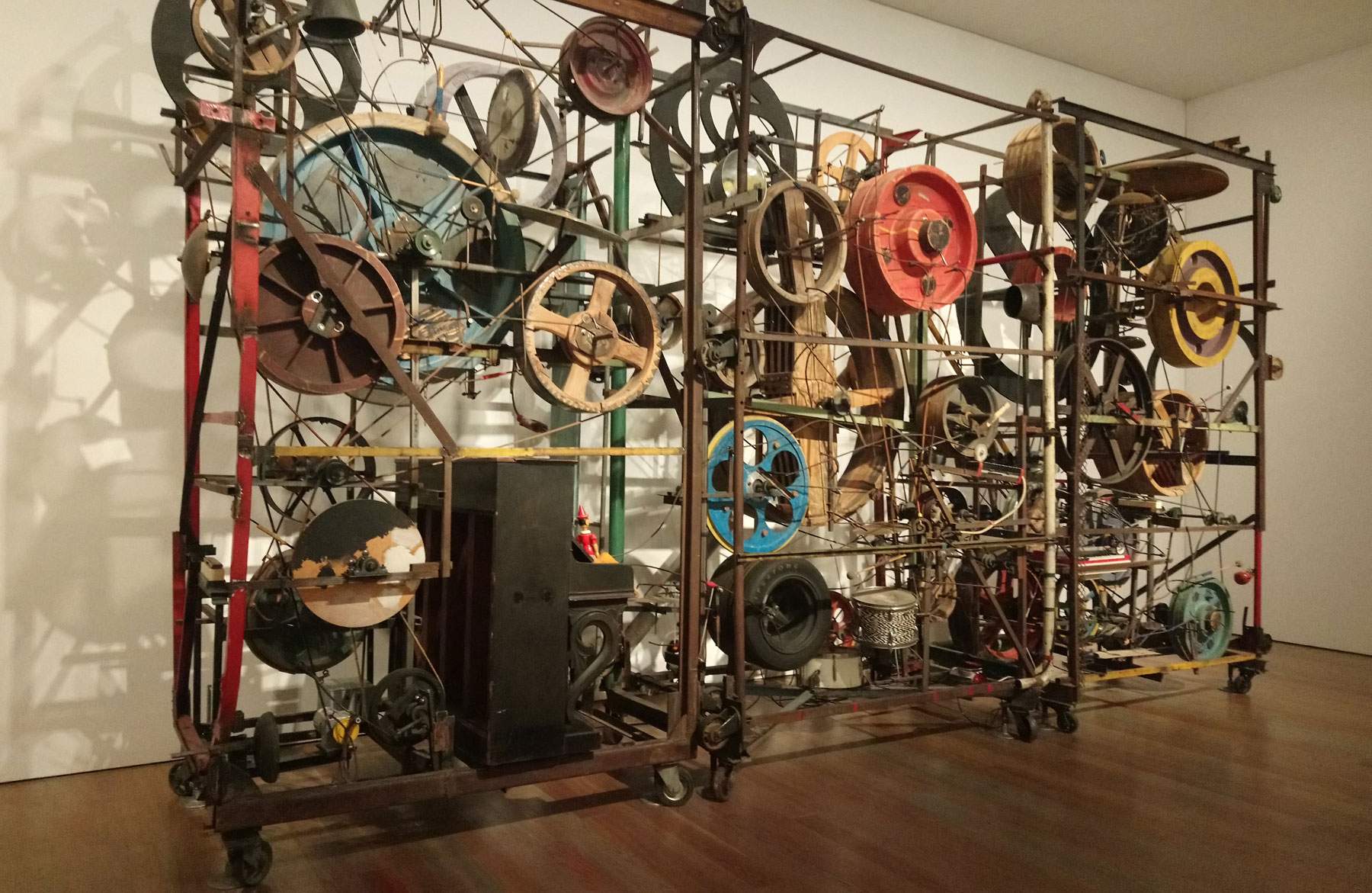

The research of kinetic art was anticipated by two important artists, Alexander Calder and Jean Tinguely. Calder is famous for inventing "mobiles," suspended mobile sculptures that move gently with the air. Calder transformed static art into a dynamic dance of shapes and colors, using metal wires, pieces of wood and painted metal sheets. His works not only explore physical movement but also the relationship between space and form, creating compositions that continually change appearance with movement. In contrast, the Swiss artist Tinguely grounded his art in a more mechanical and conceptual pursuit and created complex machines that move, make sounds and often self-destruct, built from salvaged materials and integrated with mechanisms that explored the chaos and unpredictability of movement. Tinguely challenged the traditional idea of sculpture as a static object by introducing elements of impermanence and instability. Both Calder and Tinguely, the former with his elegance and the latter with his playful and provocative approach, had a lasting impact on kinetic art, opening up new avenues in understanding movement and the interaction of artworks with their environment.

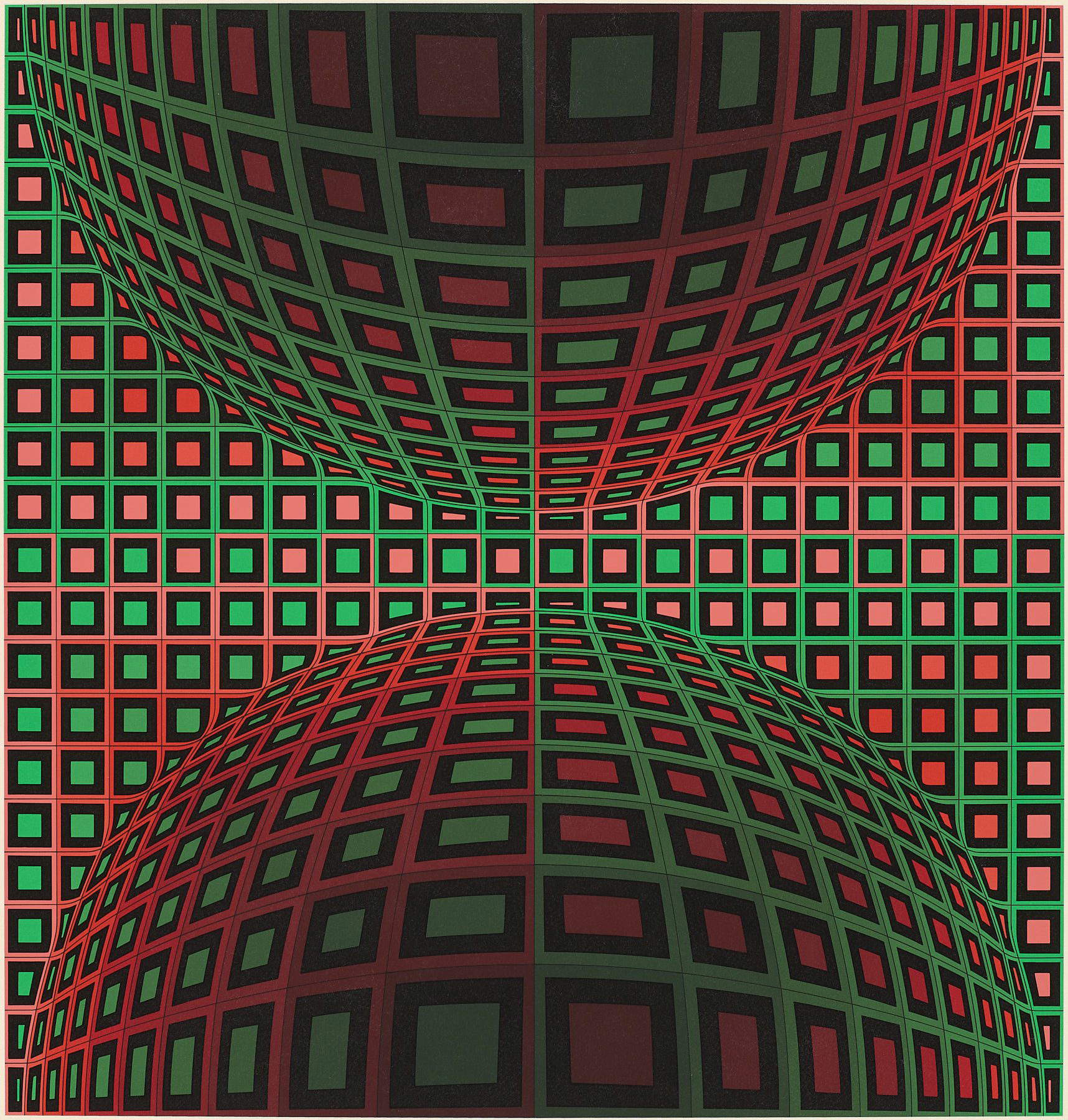

Victor Vasarely (Pécs, 1906 - Paris, 1997), a Hungarian-born artist, exhibited at the 1955 Paris exhibition: in the catalog, Yellow Manifesto, he stated that “it is not a matter of making paintings or objects move at any cost. We express a generous concept of plastic that has movement as its vehicle.” In particular, Vasarely posed himself as an exponent of that part of Kinetic Art that understood the plastic value of the work in the most illusionistic sense of forms. With him, Kineticism became Optical art, where movement is introduced into the work through optical-perceptual tools. The definition originated in the United States, when it was coined by critic William Seitz on the occasion of The Responsive Eye exhibition at MoMa in New York in 1965. Vasarely’s works are mainly “optical deceptions,” such as Homok, which was made between 1969 and 1973. The work is two-dimensional, with an abstract orthogonal form that simulates the third dimension through the study of theories of form, color and mental perception.

Pol Bury also exhibited in Le Mouvement, along with Duchamp and Calder: he made works that had a built-in motor. In Rods on Round background (1963), thin wisps of metal sprout from a round wooden surface, as if they were blades of grass, an allusion that easily hints at the artist’s early Surrealist training.

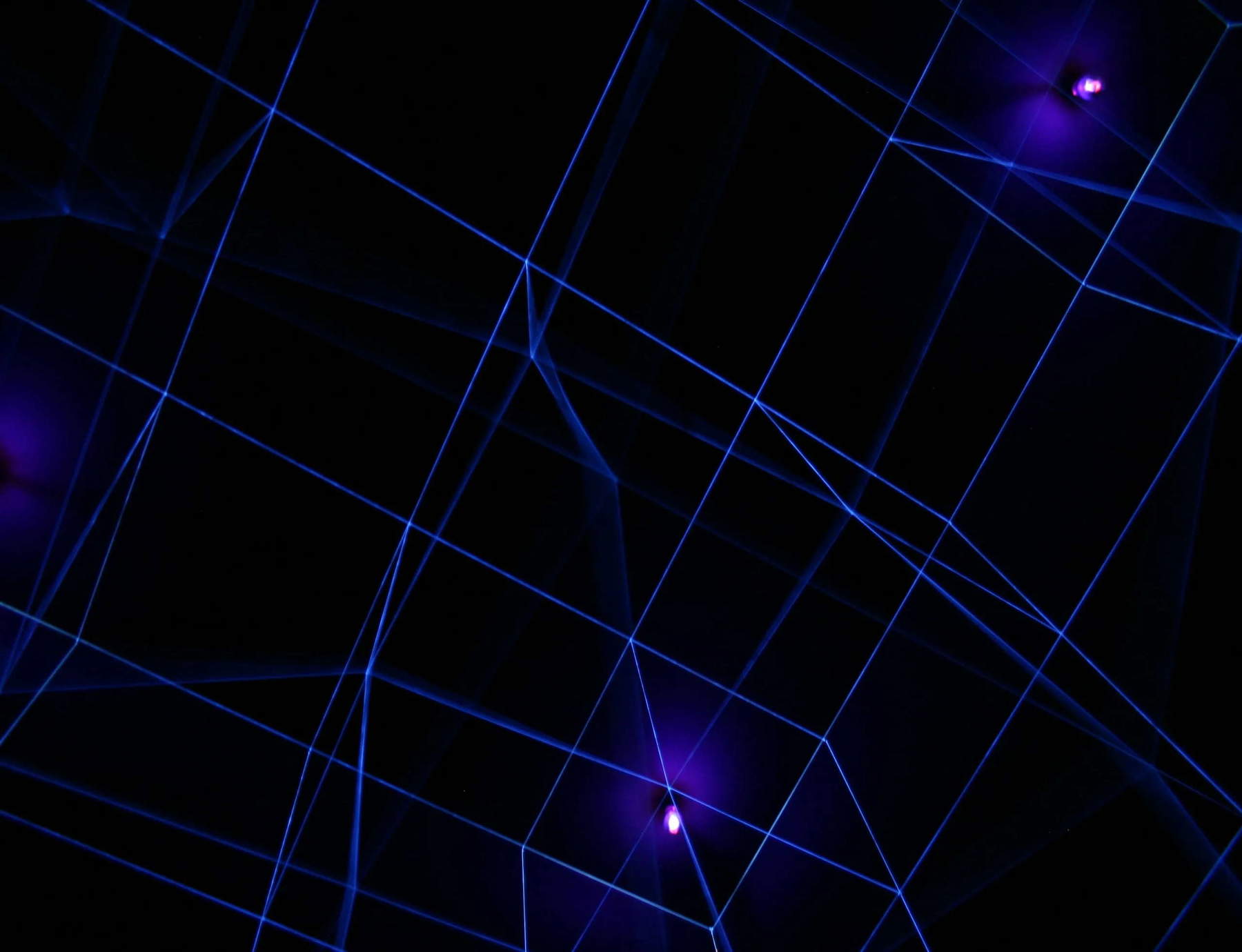

In contrast, the Venezuelan Jesús Raphael Soto pursued a quest where it was the viewer’s movement that caused a substantial change in the perception of the work. His sculptures were large in scale and quite striking, as in Gran muro panoramico vibrante, 1966, a fourteen-meter-long wall exhibited in Rome, in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna. The surface is crisscrossed by a dense interplay of lines and stripes; the visitor’s movement leads the wall to change and generate ever new impacts. Soto’s style approaches the more illusory sense of Kinetic Art but very actively involves the visitor, whose visual apparatus is continually challenged to discover the different effects of the work.

Nicolas Schöffer (Kalocsa, 1912 - Paris, 1992), a Hungarian living in Paris, explored movement in its most architectural dimension. He was also the first artist who thought of combining sound and sculpture, as he did with the Cybernetic Spatiodynamic Tower, in 1961, built in Liège, Belgium. A mechanical body more than fifty meters tall, it consists of revolving axes that rotate at different speeds, activated by built-in motors. The axes in turn move mirrors and plates that reflect light. The work is equipped with a number of sensors that record environmental data (wind, light, humidity) and forward them to computers, which in turn create an ever-changing and changing sound and light ensemble, depending on the weather situation. It is an interactive work that combines aesthetics, mechanics, and music.Schöffer deepened these ideas in 1961 with the publication of his essay entitled The Cybernetic City.

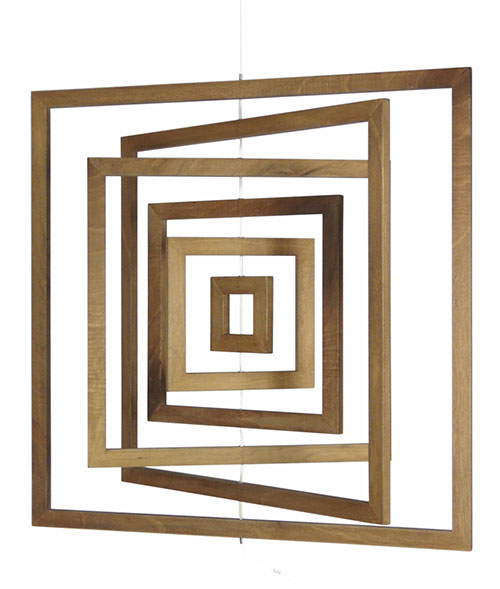

Despite the ideal aura reserved for the authors and the prominence gained by critics and essayists, there also developed a broad tendency for artists to come together in groups, in collectives where ideas were developed and activities presented as a whole that nullified the individuality of the bohemian. The preference for anonymity led to the emergence of several groups: European groupings included the Zero Group, founded in 1957 in Düsseldorf; the GRAV (Group de Recherche d’Art Visuel), founded in Paris in 1960. GRAV included François Morellet (Cholet, 1926 - 2016), famous for his geometric structures made of wire. The lattice forms produced unpredictable chromatic perceptual effects in the viewer’s eye. One of these creations is Three Superimpositions (1975).

In Italy, the artists who formed Gruppo T worked on the production of various structures. Giovanni Anceschi, founder of the group, executed several series of works, called “effects,” that explored the various formal possibilities of matter. The Fluid Paths series (helical or rotating, spiral and cubic), dating from 1962, is composed of different materials, including wood, structures made of enameled iron, polyethylene tubes and colored viscous liquids contained between two sheets of transparent plastic. The structures are attached to the wall, rotated by means of a device that allows the viewer to witness the perpetual mutation of the work.

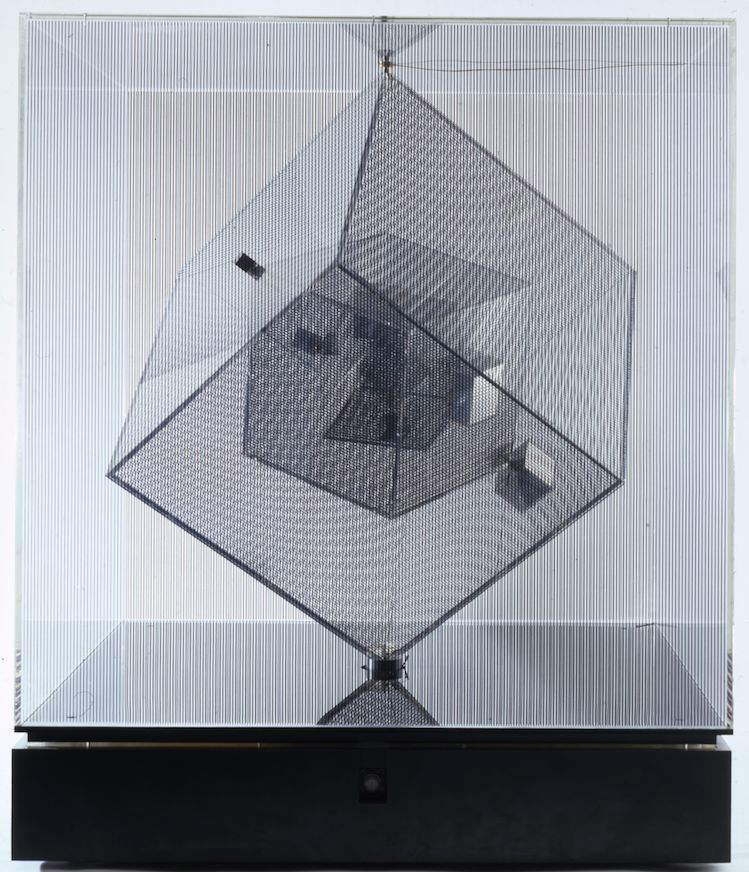

Fellow artist Davide Boriani made Ipercube between 1961and 1963. He employed micromotors and screen-printed methacrylate to make it, creating a moving cubic structure containing four additional smaller cubic forms within it. The movement of the cubes always makes the perception of the whole form new.

Gabriele De Vecchi in 1959 produced a Kicking Sculpture, presenting it at the Miriorama 3 exhibition in 1960 at the Pater Gallery: this geometric form is made of rubber, feather and elastic. The title of the work is also an invitation to aesthetic action, an exhortation of participation addressed to the viewer: some photographs remain that show how even a child can take part in the activation of this artistic structure.

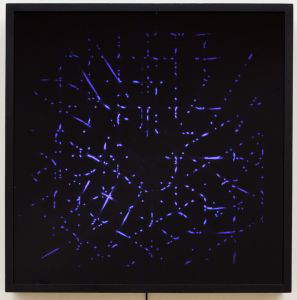

Grazia Varisco joined Group T at a later stage by creating a series of Magnetic Tables between 1959 and 1962: a metal sheet fixed on a wooden support serves as a base for a number of simply shaped magnets. Dots and lines fixed as magnets are left to a playful function offered to the viewer. Varisco’s production also employed other materials such as neon lights and micromotors, as happened in 1962 to make Variable Light Scheme R. Vod., where the same title conveys the idea of mutability.

The works of the artists belonging to Group T always proposed a reflection on the variability of the materials of the works. At times, production turned to the staging of environmental works, installations that marked the transition from kinetic and programmed works to the construction of a space that was habitable and mutable, presupposing a further opening of the work. The group’s best-known artist, Gianni Colombo, designed environments in which the viewer was induced to become aware of how, on a daily basis, he occupied a space and interacted with it. Elastic Space (1968) was exhibited at the Venice Art Biennale in 1968, where it was awarded the Golden Lion.

Unlike Gruppo T, the Padua-based group believed more firmly in the energy of collectivity, so much so that they signed their works with Gruppo N: for example the execution of Quadrati spaziali in legno e plexiglas (1961), was by Ennio Chiggio, but bore the signature of the entire collective. However, the artistic expression of Group N was not limited to a language of only works and statements. Rather, it organized a real self-managed cultural review from 1960 to 1964, carrying out its artistic journey in Padua, first in its headquarters in Via San Pietro 3 and later in the one in Piazza Duomo.

Studio N gave visibility to the most remarkable national and international experiences: artists such as Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana, Piero Manzoni but also Jackson Pollock and François Morellet exhibited here. It was a circle that cultivated encounter and availability, that sought an openness to contemporary arts aimed at promoting an ethic of life, precisely, collective. The artists were consistent in their idea of sharing, seen as a new way of handling cultural information.

The members of Group N collectively signed the closed Exhibition. No one is invited to attend, at their studio N from December 11 to 13, 1960. The front door of the gallery was barred; along with the invitation, a printout specified the purpose, which was a critique of the cultural policy of the city of Padua, with the intention of laying the groundwork for a “new society.” Group N’s provocative intent continued with a second city performance, the Bread Exhibition, where baker Giovanni Zorzon displayed his “edible forms” for a day. On this occasion, Group N strongly challenged the myth of the artist figure, rejecting it in favor of a collective experience. The exhibition was still held at the St. Peter’s Street venue, bursting onto the city scene and overturning the traditional exhibition principles of art. It was immediately commented on by Luigi Barzini’s famous article published on June 18, 1961 in Corriere della Sera, “Art and Salami,” where he wondered how far art would go.

The personalities that formed Group N were distinct from each other and, at the same time, each indispensable to the execution of the collective works. Ennio Chiggio worked with wood and light sources; on the occasion of the XII edition of the Lissone Prize, initiated in September 1961, he exhibited Interference and Light Refraction, where light was perceived dampened, refracted due to the affixing of a metal retina; also worked with light sources Alberto Biasi in 1969, when he made the Great Rainbow Plunge, a work consisting of a flat structure placed on the ground, within which a number of crystal prisms, light sources and electromotors were placed. This set-up projected downward moving waves of colored light. Suspended structures executed with the use of wood, canvas, elastic threads on frames characterized the collaboration of Edoardo Landi, whose compositions offered, in their suspension, ever new perceptions of matter due to the movement of the works. Manfredo Massironi, too, composed forms with simple materials such as cardboard, wire, glass, and wood, fitting fully into the creative spirit of the group (for example, with Struttura trasparente con occhielli, dated 1960). Beyond the execution of autonomous structures, there were also projects for traversable spaces: Aquatronic was the project born out of Chiggio’s collaboration with Massironi in 1968 for the setting of a fountain with water features designed for the “III National Marble Exhibition,” in Carrara.

When in 1962 Bruno Munari organized the exhibition Arte programmata together with Umberto Eco and Giorgio Soavi (artistic consultant of Olivetti’s advertising department), the artists of Group T and those of Group N participated, emerging on the international cultural scene. Also presenting at the exhibition were artist Enzo Mari (Novara, 1932 - Milan, 2020) and Bruno Munari himself, who adhered to kineticism as early as 1956 with his Useless Machines: painted geometric forms, suspended and subject to oscillation in the environment in which they are installed. Made with materials and techniques derived from serial and industrial production, they were architected by Munari to return the one and only aesthetic function, unrelated to the work’s pretended technical functionality.

New, radical objects straddling art and design were seen at the Arte programmata exhibition. The corporate project of Giorgio Soavi, a representative of Olivetti, was to research “new means and new forms of visual communication”: these were years of great openness, a thinking beyond the box that led the industry to have an affinity with “the programmed.” The theme of programming was indeed relevant to Olivetti in the second half of the 1960s, whose electronics research program involved designer Ettore Sottsass (Innsbruck, 1917 - Milan, 2007) for the Elea 9000 and Elea 9003 computers.

|

| Kinetic and programmed art. History, style, artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.