Jannis Kounellis (Piraeus, 1936 - Rome, 2017), an artist of Greek origin, naturalized Italian, was one of the main exponents ofArte Povera, whose modus operandi consisted of the recovery and reuse of discarded materials to create installations, which aimed to expand beyond the physical limits of the painting by forging a link between the work and the environment around it.

Kounellis joined the other poverists around 1967, rather naturally since the painter, starting from his early beginnings on canvas, akin to abstractionism, had already a few years earlier manifested a certain crisis regarding painting and had begun to introduce elements similar to performance. Classical music, live animals and natural materials such as charcoal would become recurring elements in Kounellis’s works, which remained active until a few years before his death in 2017.

As an artist and as a person, Kounellis always felt the theme ofpolitical ideology very close to him, as he saw with his own eyes the civil war in his native Greece, a trauma that brought him a relationship of impatience with his homeland. In addition, Kounellis often manifested a tendency toward disappointment and rethinking toward certain conventions of art, to which he did not fail to respond through his installations, to a kind of settling down on patterns already traveled in his youth that is found in the last phase of his life.

Jannis Kounellis was born in Greece, in Piraeus, on March 23, 1936: here he remained until his twenties. During his childhood he was in the midst of the Greek civil war of the years 1946-1949, and this particular situation greatly influenced the development ofKounellis’s political identity and also conditioned his artistic vision. As a teenager, Kounellis had already made some works and began taking drawing classes, and then chose to enroll first in theAthens Art Institute and then in the School of Fine Arts, where, however, he stayed only one year due to friction with his professors.

After this episode, Kounellis left Greece and continued his artistic education away from his homeland, deciding to drastically break with his origins and even going so far as to disown them for a long time. He then moved to Italy, to Rome, precisely on New Year’s Day 1956. He enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in the Italian capital, where he had the opportunity to study with Toti Scialoja, who turned out to be a great point of reference for his training in the informal sphere and his knowledge ofabstract expressionism. In general, the cultural environment of Rome was very important for the artist, as it allowed him to broaden his horizons by finding, by his own admission, lively and new ferments that were totally lacking in Greece.

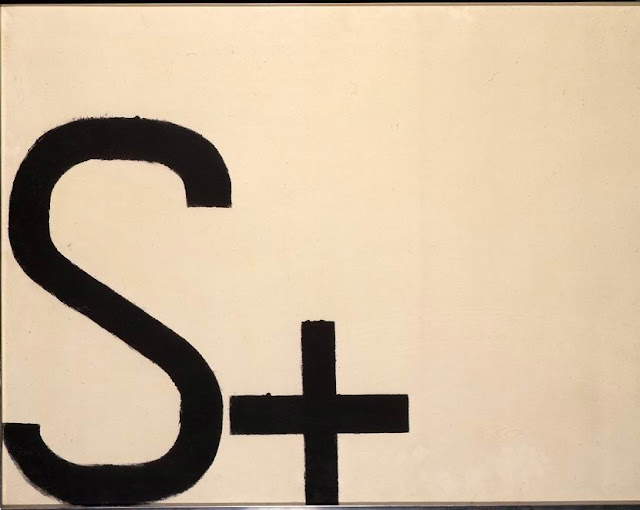

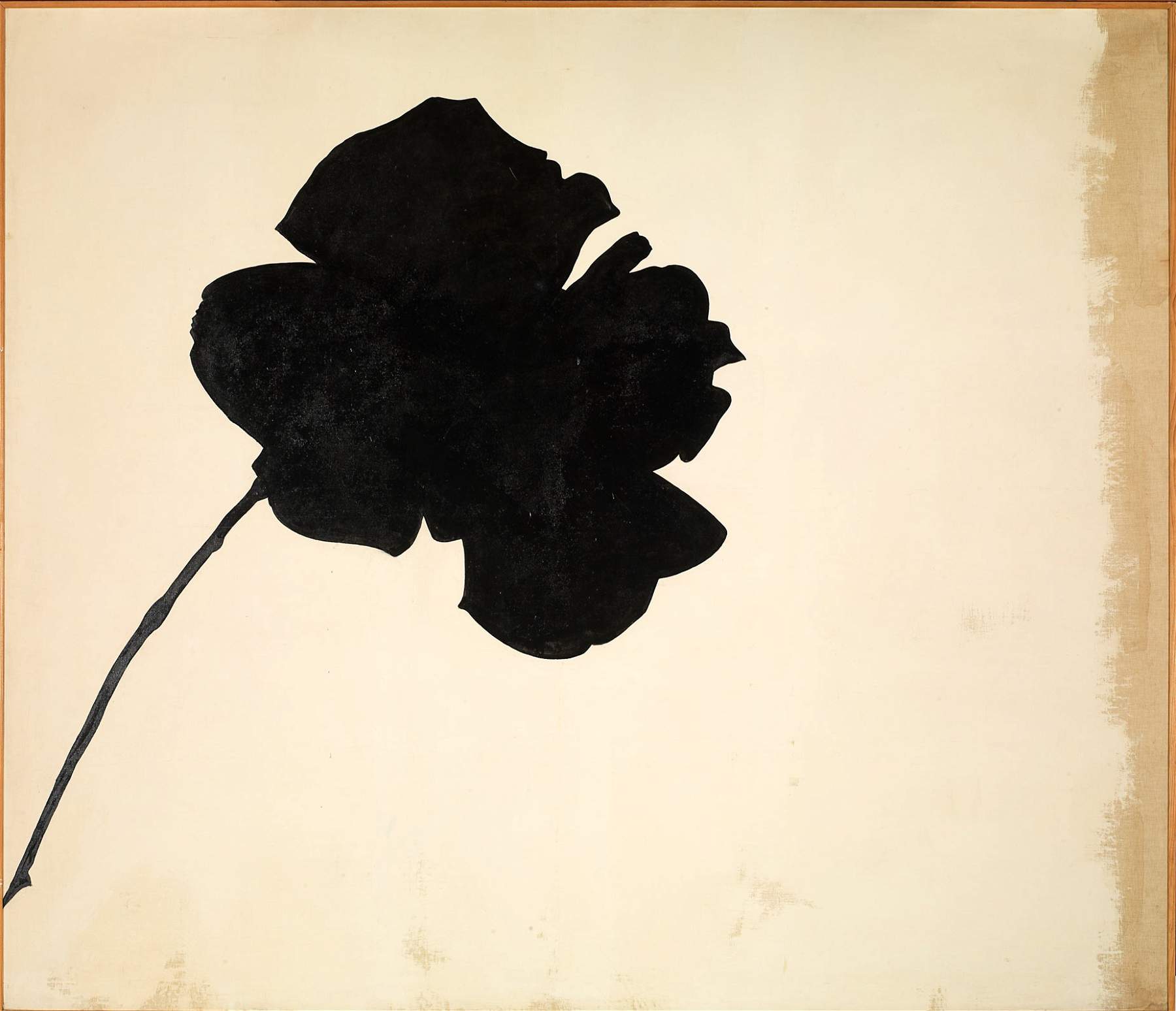

Kounellis inaugurated his first solo exhibition in 1960, exhibiting works made during his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts. The exhibition, which was held at the Tartaruga Gallery in Rome, was titled The Alphabet of Kounellis, as it was a series of white canvases on which large letters of the alphabet, as well as numbers and other signs, stood out, painted with black acrylic paints. A second solo exhibition was then held in 1964 in the same exhibition space. In 1961 he participated in his first group show as part of the XII Premio Lissone, with a work similar to those already exhibited in the first solo show, inaugurating a long series of participations in various Italian and European exhibitions.

A pivotal year for Kounellis was certainly 1967. In fact, at this date first of all a further evolution of his art occurred, whereby he increasingly abandoned the canvas to appropriate the surrounding space through installations, in line with a generalized crisis with respect to painting and the avant-garde that was manifesting itself in contemporary art. Moreover, in the same year he began his collaboration with the artists who would form the Arte Povera collective. In fact, he participated in several of the group’s exhibitions: Lo spazio degli elementi: fuoco immagine acqua terra at the Roman gallery Attica, Arte povera - Im-spazio at the gallery La Bertesca in Genoa, and the following year he was also present at the exhibition-event Arte povera più azioni povereat the Antichi arsenali in Amalfi. Also in 1968, Kounellis participated for the first time in an exhibition in the United States, namely a traveling group show entitled Young Italians. The 1980s constituted the period of Kounellis’s consecration as an artist of international prominence, thanks to the incessant exhibition activity that took place in Europe and the United States, including solo shows and dedicated retrospectives, which had been going on since the 1970s. The artist later became a professor of painting in Germany, specifically at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, between 1993 and 2001. He passed away in Rome on February 16, 2017, following heart problems.

The artistic intent of Jannis Kounellis was immediately distinguished from that of his masters, including the aforementioned Toti Scialoja, by a very personal vision of art and the message to be spread through it, an aspect that appears to have been present in Kounellis since his years of study at theAcademy of Fine Arts in Rome. Kounellis soon identified a recurring pattern to be presented on the canvas, consisting of dark typographic signs (letters of the alphabet, numbers and signs) silhouetted against light-colored backgrounds, creating a language reduced to the bone and never purely aesthetic, but rather accessible and understandable to all. The choice to work with everyday materials also expresses Kounellis’ precise desire to eliminate any end in itself approach to the works in order to make art a universal language. This is, this, the period of the works Untitled dated between 1958 and 1960. Kounellis will deliberately title a large part of his production in this way, to cancel any personal input of the artist and leave the viewer free to find his own free interpretation.

The works dated to the 1960s coincided with Kounellis’ participation in the exhibitions of the Arte Povera group. This was, this, a collective of artists who, in complete antithesis with traditional art, recovered “poor” waste materials precisely, such as earth, wood, plastic, textiles and the like to make installations designed with the aim of eliminating any physical limitation given by the painting and instead creating a link between the work itself and its surroundings. Kounellis fits into this context rather naturally, as he had already for some time been creating an embryonic form of performance by painting live during his exhibitions and, once the work was completed, declaiming aloud the letters and signs he depicted from time to time. During these events, Kounellis took care of every detail, including his attire: he used to wear a painted canvas reminiscent of the same clothes worn by Hugo Ball in the Dadaist evenings at Zurich’s famous Cabaret Voltaire in the early 1900s, thus explicitly paying homage to the early avant-garde.

The artist’s tendency toward performance continued when in 1964 Kounellis made his first works with musical accompaniment, for example, in another Untitled, Kounellis painted the notes of the first three bars of Sidney Bechet’s 1952 song Petite fleur on the canvas, playing it while admiring the work. Meanwhile, some important turning points in contemporary art were occurring. In the second half of the 1960s, in fact, artists were beginning to rethink the avant-garde as no longer considered satisfactory, but rather outdated, as well as an expression of an individualism of the artist that no longer had any reason to exist. We had now entered the ideological temperament that would lead to the protest movements of 1968, and Kounellis is fully involved in it by beginning to have profound crises concerning painting. The works of this period turn out to be basically happenings, in which music was present more and more predominantly than in previous years.

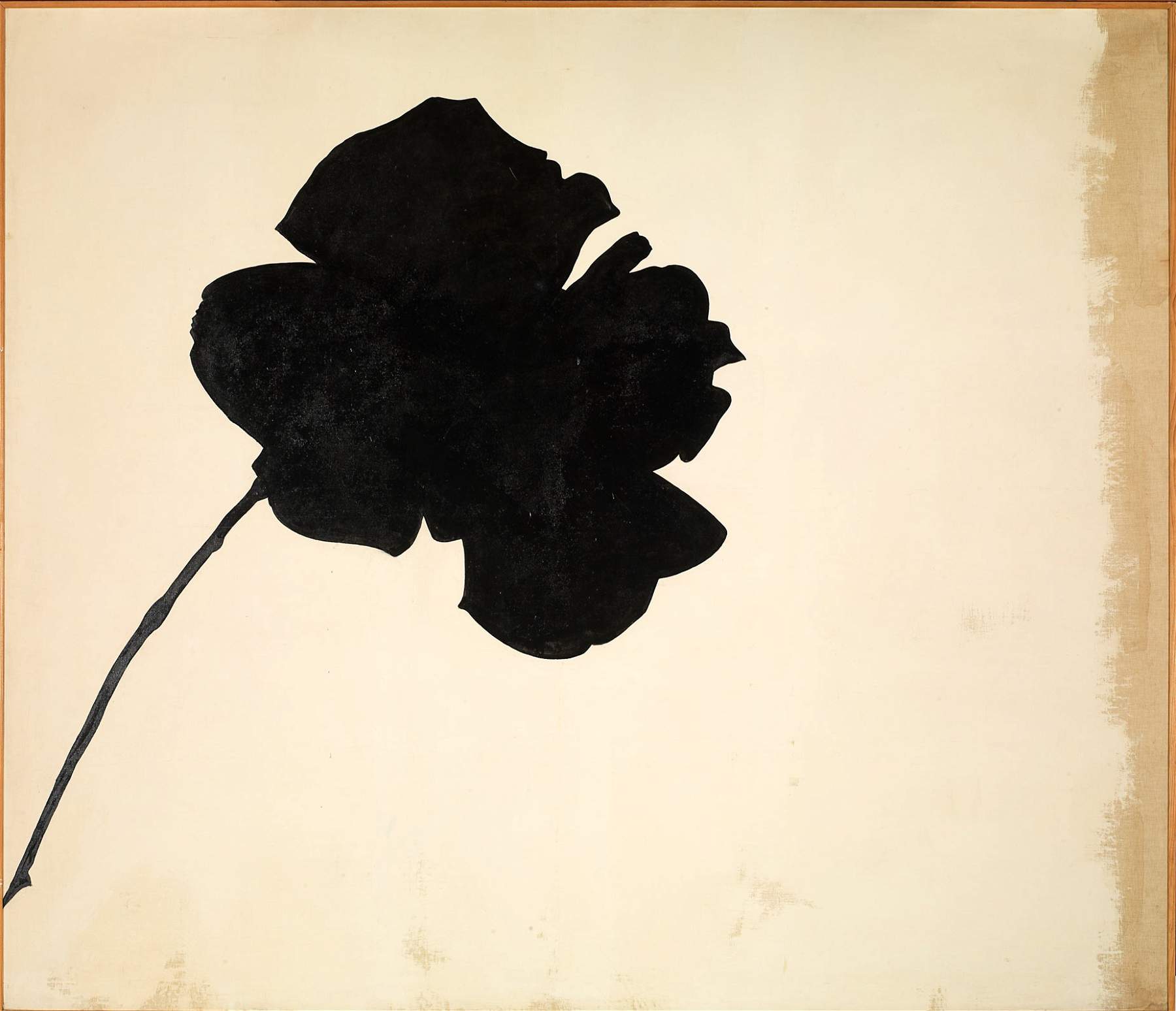

Kounellis’ urgency, well in advance of other Italian artists, was to succeed in establishing as direct a relationship as possible between art and objective reality. He thus began to experiment with different materials and to combine them with the presence of live animals, for example in another work Untitled he applied three white fabric roses to the canvas temporarily with clips, and affixed around them some cages with live birds inside. The temporary application of the cloths was intended to symbolize the fragility of linguistic systems and codes.

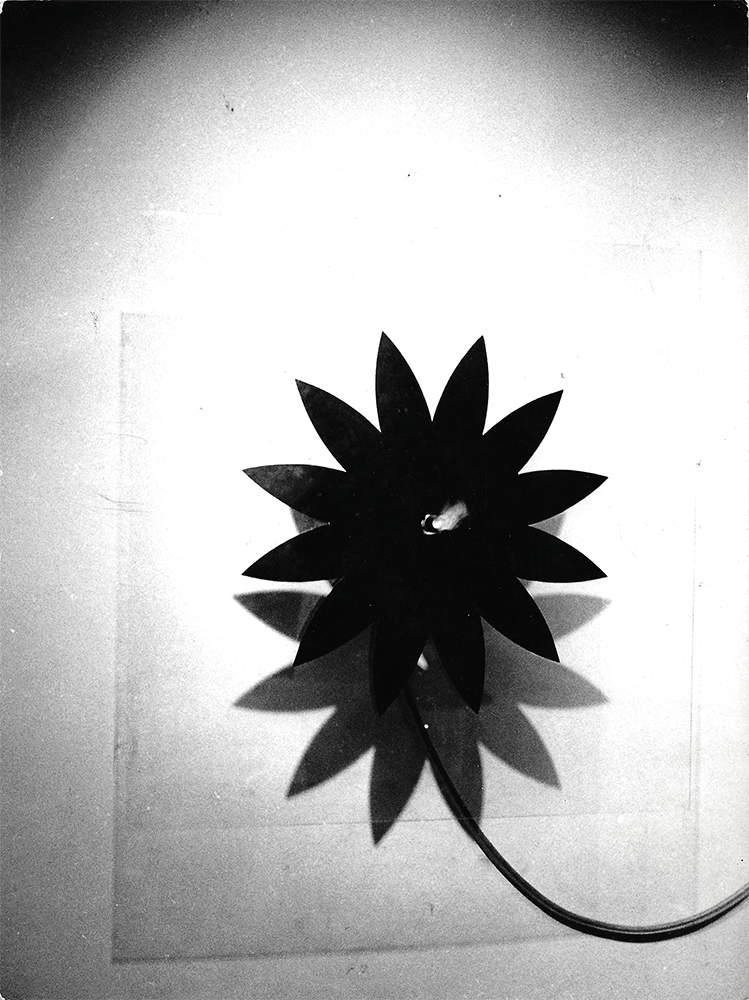

Another very significant work with regard to overcoming the two-dimensionality of the canvas is Daisy of Fire (1967), which consisted of a metal flower at the center of which was placed a manifold of a gas cylinder from which a blue blaze emanated. The flame was a direct reference to the element of fire, which was very dear to Kounellis as it traversed the centuries unscathed, being discovered by man in prehistoric times, then used in the Middle Ages as a means of punishment and martyrdom, to its recent application in modern industry. Another element that Kounellis frequently worked with and presented for the first time in the Arte povera - Im-space exhibition of 1967 was coal, placed inside a metal structure called precisely a “coal box.” The artist was very fascinated by this combination of container and content, in fact for him it was a metaphor for the encounter between the artificial element of the coal box, and the natural matter inside it, which leaves its tangible traces since coal dirties and stains everything it comes in contact with.

At the end of the 1960s, Kounellis also tried his hand at some stage sets for theatrical performances, which were often not thought of simply as a background element on which the acted scene took place, but were intended to bring in disturbing elements that were intentionally disturbing both to the audience but also to the actors, who were forced to act in an unusual way. Fire later returns as a protagonist in an installation designed for the Iolas Gallery in Paris, in which Kounellis again uses gas cylinder manifolds by inserting them along the walls of the room. Once the manifolds were turned on, the gas flames made it impossible for the viewer to enter the room, which in the meantime had filled entirely with smoke, thus staging the distance between the artist and the viewer of his works, along with the metaphor of the flaring up of ideological and political dissent in 1968.

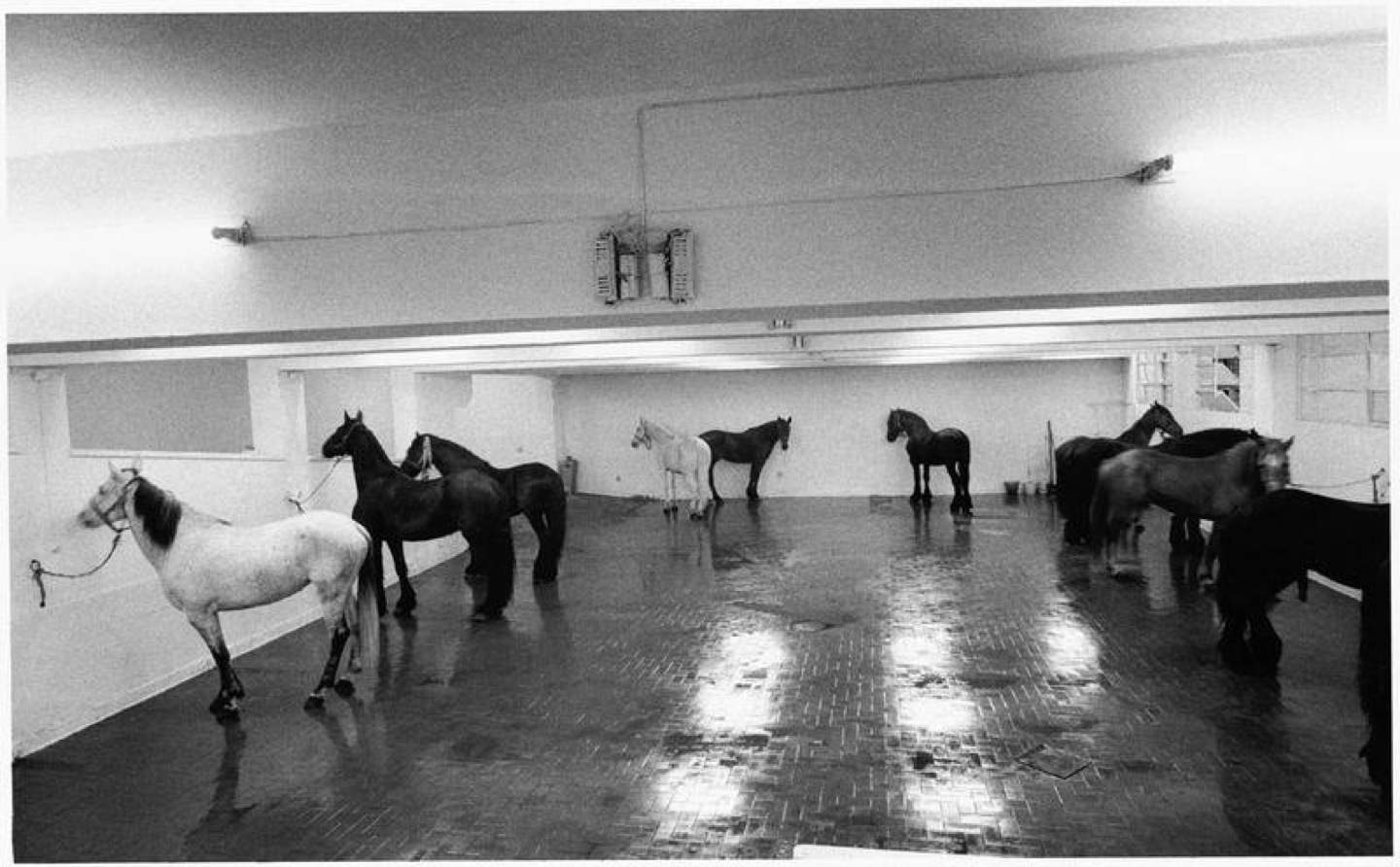

A further turning point in Kounellis’s experiments occurred in 1969 with the installation Untitled in which some live horses, a recurring element in the artist’s works, appear for the first time. The work was designed to inaugurate the new premises of Fabio Sergentini ’s L’Attico gallery and involved twelve live horses being tied to the gallery walls at regular intervals. The viewer, immersed in a multisensory moment that went to stimulate mainly the sense of smell, as well as sight and hearing, nevertheless remained inhibited and uncomfortable in front of the cumbersome presence of the animals and tended in an almost unconscious way to stay at the sides of the space available. The horse was not chosen at random; rather, it was a direct reference to ancient art, thus creating a clash between past and present, but also between culture and matter.

Industrial noises (such as those generated by lit gas cylinder manifolds) or natural noises (such as those produced by horses) gradually gave way in the 1970s to classical music, which was used both to engage the audience again in active listening and as a European cultural and ideological reference regarding the current political situation, for example, choosing with clear political intent the Và pensiero from Verdi’s Nabucco for a performance in a 1970 Achille Bonito Oliva exhibition. In another 1973 performance, on the other hand, Kounellis arranged fragments of a plaster statue depicting the Greek god Apollo and a stuffed raven on a table, then presented himself to the audience wearing a mask while at the same time a flutist, every two minutes, played excerpts from Mozart, thus declaring all the despondency felt by the choices of politics and the artist’s inability to effect change in a society that was by then completely individualistic. Between the 1970s and 1980s, however, a kind of disappointment took over in Kounellis due to the fact that Arte povera gave way to more commercial logics dictated by galleries, and consequently his works became more somber.

In 1974 pyramids formed with powdered coffee and presented to the public as if they were merchandise for sale made their first appearance, an element that would recur later on and that carries a double meaning: on the one hand it is a way to continue the reasoning about the sense of smell, which had already begun with the presence of live animals, and on the other hand coffee is used as a reference to the Mediterranean culture of origin and the huge commercial trade.

The 1980s constitute a period of total disenchantment for Kounellis, who begins to eliminate the living elements in his works, increasingly substituting soot for fire and stuffed animals for live ones. In the 1990s the artist reworked some of the solutions he had already undertaken in the past with a new and more meditative maturity, heading toward a greater awareness of monumentality. One of the most significant works of this period is Offertorio (1995), installed in Piazza Plebiscito in Naples, consisting of a metal slab from which tongues of fire spilled out in the center of the square, while at the same time two hundred closets supported by heavy ropes were hung on the vault of the portico of the Church of S. Francesco di Paola, confirming a dialogue between different materials that are handed down through history and will remain for future generations.

He also created, also in 1995, another work of great political significance: the Monument to the memory of Concetto Marchesi, Egidio Meneghetti and Ezio Franceschini also known as Resistance and Liberation for the courtyard of the University of Padua, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Italian Resistance. In the early 2000s, he made a peculiar installation in the GNAM - National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome, namely a large labyrinth made of sheet metal in which various elements of his art such as coals, piles of stones and others were placed. He will continue to make various installations in Italy until 2012.

Kounellis’s works, most of which are untitled, can be found in several Italian museums. Starting in northern Italy, they include the Museo San Fedele Sacello degli Asburgo, Milan, the Centro per l’arte contemporanea Luigi Pecci, Prato, and the Centro Arti Plastiche, Carrara. At the center, works by Kounellis can be found at MAXXI - Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo sez. d’arte figurativa, Rome. The work Margherita di fuoco (1967) is also kept in Rome, at the Mario Pieroni Collection.

Finally, in southern Italy it is possible to see his works in Naples, both in the Museo d’arte contemporanea Donnaregina MADRE and in the Museo di Capodimonte; at the Reggia di Caserta in the Terrae Motus Collection; and finally in Palermo in the Palazzo Riso - Museo Regionale d’Arte moderna e contemporanea.

|

| Jannis Kounellis, the Greek of Arte Povera. Life, style, works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.