The most representative figure ofAmerican art in the 1940s and 1950s was Jackson Pollock (Cody, 1912 - Long Island 1956), a restless and rebellious man, addicted to alcohol, which he could not do without throughout his life and which led to his early death. He was one of the leading exponents ofAbstract Expressionism, one of the best known artists in America to whom even Life magazine devoted a page. Supported early on by collector Peggy Guggenheim, the irascible Pollock gave a major breakthrough to abstract art through the dripping technique.

Interested in American history, the artist began to delve into Native culture, which greatly influenced his work, just as he was also influenced by Surrealism, whose leading exponents came to New York following World War II, bringing innovative elements to American painting. Pollock also adhered to the psychoanalysis of Carl Gustav Jung , for whom, on an unconscious level, all humanity shares collective archetypes, or primary forms that have the same meaning for everyone. Pollock met and married painter Lee Krasner, with whom he moved near Long Island, although the painter’s fidelity was quite fleeting.

|

| Jackson Pollock |

Jackson Pollock was born on January 28, 1912, in Cody, in the state of Wyoming, to a family of modest origins. He spent his youth between Arizona and California. In 1929 he joined his brother in New York City, where they both moved to and attended the Art Students League in which they had the opportunity to take classes from painter Thomas Hart Benton, who was one of the leading exponents of American realism. What greatly impressed the young Pollock was not so much Benton’s preference for American landscape subjects, but rather his use of color and his strong independence: two elements that characterized Pollock’s art. From 1935 to 1943 he worked as a muralist for the Federal Art Project whose goals were to create employment opportunities for unemployed and underprivileged artists, to produce artwork intended to beautify public buildings, and to educate the American people about art. It was during this period that the American artist looked with keen interest at the great Mexican masters, who in fact devoted themselves to mural painting. These included José Clemente Ozorco, Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros: the latter had a strong hold on Pollock because at a seminar held in New York the Mexican artist introduced the use of pure color.

As early as the 1940s Pollock enjoyed some recognition thanks to the support of critic Clement Greenberg, one of his main supporters, and collectors and gallerists Betty Parsons and Peggy Guggenheim. In 1943 MoMa (Museum of Modern Art) purchased a Pollock work, The She-Wolf (1943), after the exhibition the year before, Art of This Century held at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery-museum; Peggy Guggenheim herself offered Pollock a contract that would last until 1947. In the early 1940s he also participated in the exhibition Abstract and Surrealist Art in America, which was held at the Brandt Gallery in New York. In 1950 the American artist’s first solo exhibition was held, organized by Peggy Guggenheim at the Museo Correr in Venice, where Jackson, however, was not present because he did not like to travel outside the United States. After the Venetian solo show Pollock also landed in Paris at Studio Paul Facchetti, which showed his drippings to the French public in 1952. In 1945 Jackson met and married the young painter Lee Krasner with whom he opened a small house-studio near Long Island. It was here that Pollock began experimenting with his famous painting technique, which consisted of spontaneous painting achieved by dripping color directly onto the canvas. The canvases were spread out on the floor (and already the position was decidedly unconventional), and the artist began to make use of those techniques that would be destined to accompany Pollock’s name: this is thedripping technique (dripping). This new way of proceeding and the innovative relationship with the canvas laid the foundations ofaction painting, also called gestural painting or more generally abstract expressionism: it was an “all-out” style of painting based more on the pictorial elements (canvases, color and space) than on the subjects represented. Abstract expressionism was also associated with other artists of the American school such as Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, and Barnett Newman . The years between 1945 and 1950 were Pollock’s most creative and intense: in fact, his most famous canvases, Enchanted Forest (1947), Number One (1948), One (1950), fit into this period. The irascible painter’s fame increased day by day, and this was compounded by a cover that the American magazine Life, dedicated to him August 8, 1949 that asked “is he one of the greatest painters in the United States?”: these questions were answered in the affirmative by collectors who began to buy the young painter’s works. After such a fervent artistic career, Pollock died at the age of forty-four on August 11, 1956 of a car accident caused by his drunkenness.

|

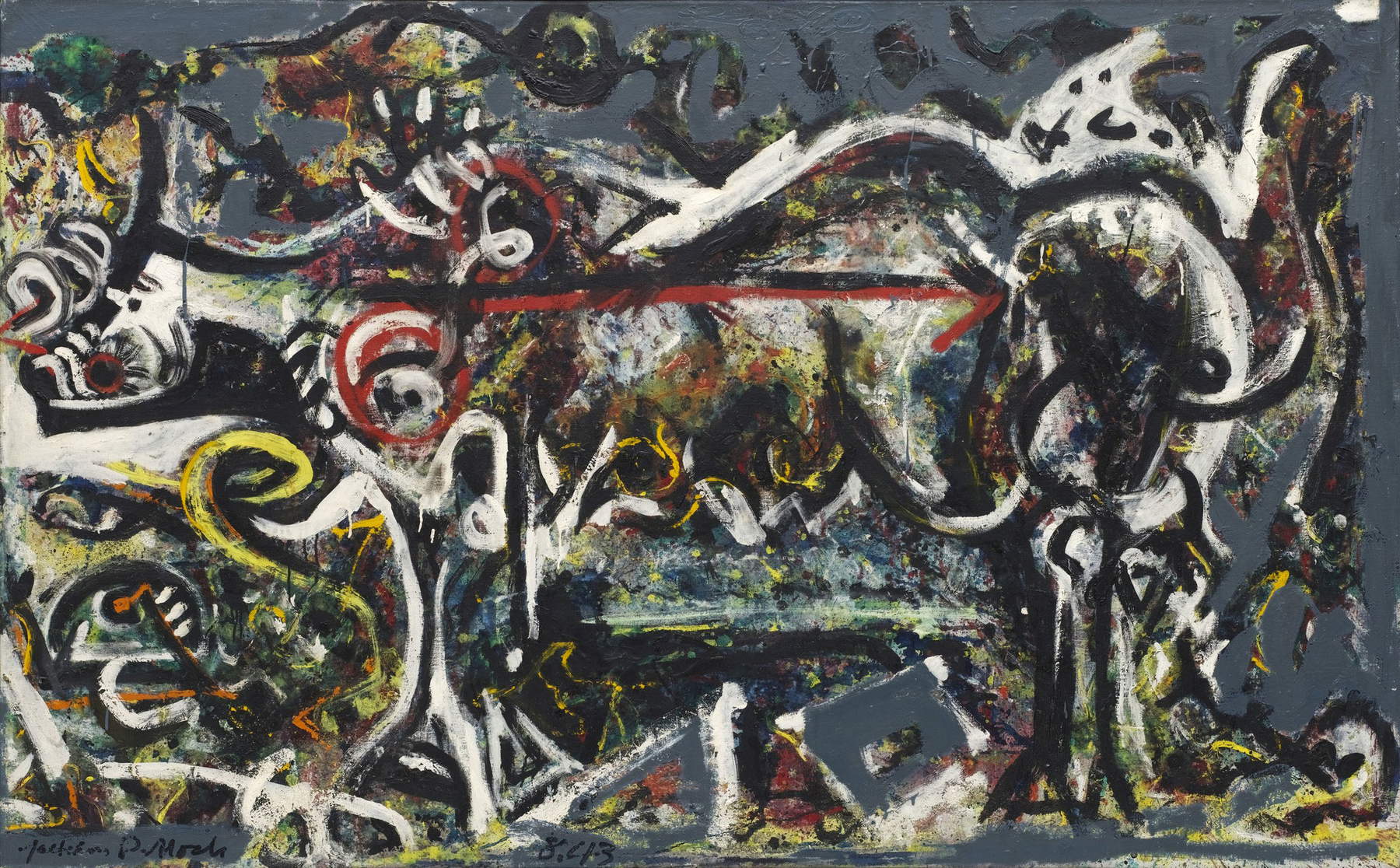

| Jackson Pollock, The She-Wolf (1943; oil, gouache and plaster on canvas, 106.4 x 170.2 cm; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Jackson Pollock, The Moon Woman (1942; oil on canvas, 175.2 x 109.3 cm; Venice, The Peggy Guggenheim Collection) |

|

| Jackson Pollock, Enchanted Forest (1947; oil and alkyd enamel on canvas, 221.3 x 114.6 cm; Venice, The Peggy Guggenheim Collection) |

At first glance Pollock’s canvases may appear to be labyrinths, sinuous shapes twisting around themselves, an irrepressible explosion of color in which the viewer’s gaze is lost in this space that seems to have no center. Yet Pollock, through the simple act of moving the canvas off the easel and laying it on the ground, then dripping the color using only the principle of randomness, showed that it was possible to have another relationship with the canvas and with art more generally. This was a different relationship from the cold and rational one that characterized the works of such a fundamental artist for American art as Piet Mondrian was: Pollock’s was a more direct, impulsive and almost visceral relationship. Pollock’s early years took the form almost of a kind of practice on works by the great masters such as Michelangelo, Tintoretto and Rubens , which are evidenced by some drawings preserved at the Pollock-Krasner Foundation in New York: from these early drawings already emerges the intrinsic energy perceptible from the twists of the bodies, the anatomy and the force they give off.

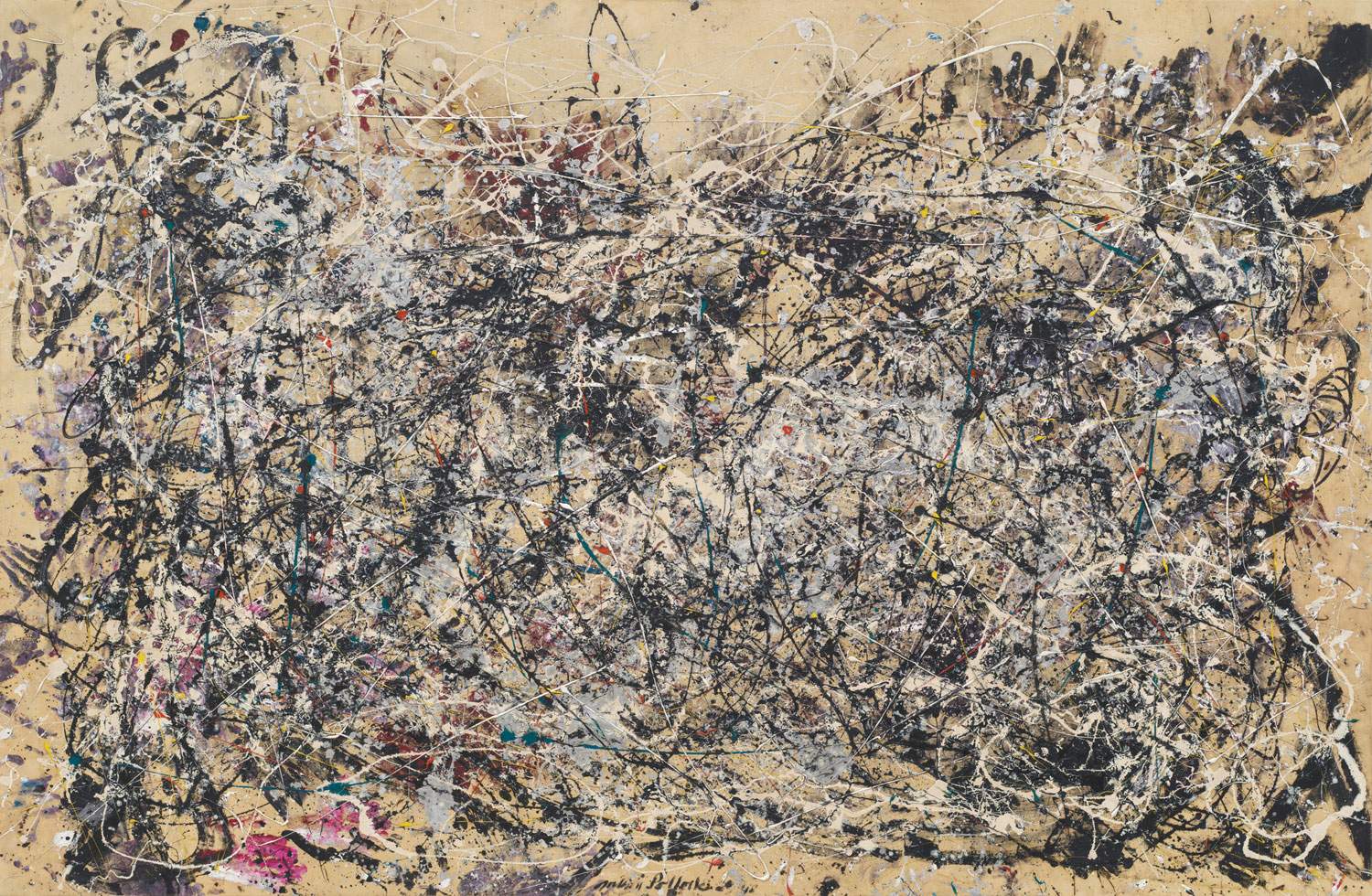

In the early 1940s Pollock became interested in the exploration of primitive subjects and mythological themes: the example that best represented this investigation of his was The She-Wolf (1943): the animal depicted here may allude to the she-wolf that suckled Romulus and Remus, according to the legend that tells of the founding of Rome. Pollock explained in 1944 that "She-Wolf came about because I had to paint her." Although at this time Pollock had not yet arrived at using the dripping technique that made him world-famous, it is already possible to observe splashes of color on the canvas, some parts showing forms devoid of lines and color in which it is possible to sense a first step toward abstraction. The she-wolf, advancing to the left, is made of thick black and white lines. Her body is covered with heavy lines, stains and illegible calligraphic marks. The protagonists of the early works were thus totemic subjects that united Surrealist imagery, in which Pollock was briefly interested, and mural painting in the canvas. In the work The moon woman (1942), Pollock was influenced by the poet Charles Baudelaire and French symbolism. In the center is a lone woman emerging from the background, and at the sides are mysterious symbols related to the archetype of femininity. The tapered body rendered by a simple stroke of a black brush contrasts with the eerie face that refers to the female figures depicted by Picasso in Demoiselles d’Avignon (1906-07). It is likely, in fact, that Pollock saw the exhibition that the Museum of Modern Art in New York dedicated to him in 1942. From these early works emerged themes intimately connected with nature, magic and symbolism, characteristics that nevertheless remained even of the painter’s more mature artistic output. In the following years the tendency toward abstraction was increasingly bursting out, as in Number 1 (1948). The work was exhibited, in the same year, for the first time at the Betty Parson Gallery in New York. Sales were disappointing and critical reviews negative, yet it was not until the following year that Life magazine featured Pollock with his arms crossed, a cigarette dangling in his mouth and under the question, “Is he the greatest artist in the United States?”

As the artist moved around the canvas, he let color drip onto the surface so that it emanated a strong energy: black and white lines converged, creating an intricate web of color. The way the color sits on the plane suggests the speed and force of the artist’s progress as well as in Silver over black, white, yellow and red (1949). In Number 8 (1949), on the other hand, Pollock’s line takes on different forms, as the critic Frank O’Hara had explained that the artist, through his ability to thin, thicken and extend one of the simplest elements such as the line, was able to nullify space, depth and the hierarchy of pictorial elements.

Pollock’s surfaces are physically present, drawing the viewer into direct confrontation with the abstract field of the canvas. Autumn Rhythm was made in 1950, and is one of the painter’s most famous works. Pigment was applied by a variety of means: knives, sticks and hands. There is no central focal point; every part of the surface has the same meaning. The size (266 x 525 cm) also assumes significant importance, as the viewer, being confronted with such an overwhelming painting, feels enraptured. Following the swirling, lush lines, one can almost imagine Pollock’s “ritual dance.” There is a lack of forethought in these works , which, however, does not translate into a lack of control since Pollock, as he had to say in various interviews, managed the flow of paint. For Pollock, art had to convey meaningful and revealing content. In 1945 there was an exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery that exhibited paintings by Joan Miró, an artist Pollock greatly admired, and which probably gave a boost to the American artist’s art. His canvases that Pollock admired were the Constellations, a series of works made between 1940 and 1941 and composed of a number of shapes scattered across the canvas and connected by a thin line that invoke a stellar metaphor. Some critics claimed that Miró was a direct precursor to the works that Pollock would later execute.

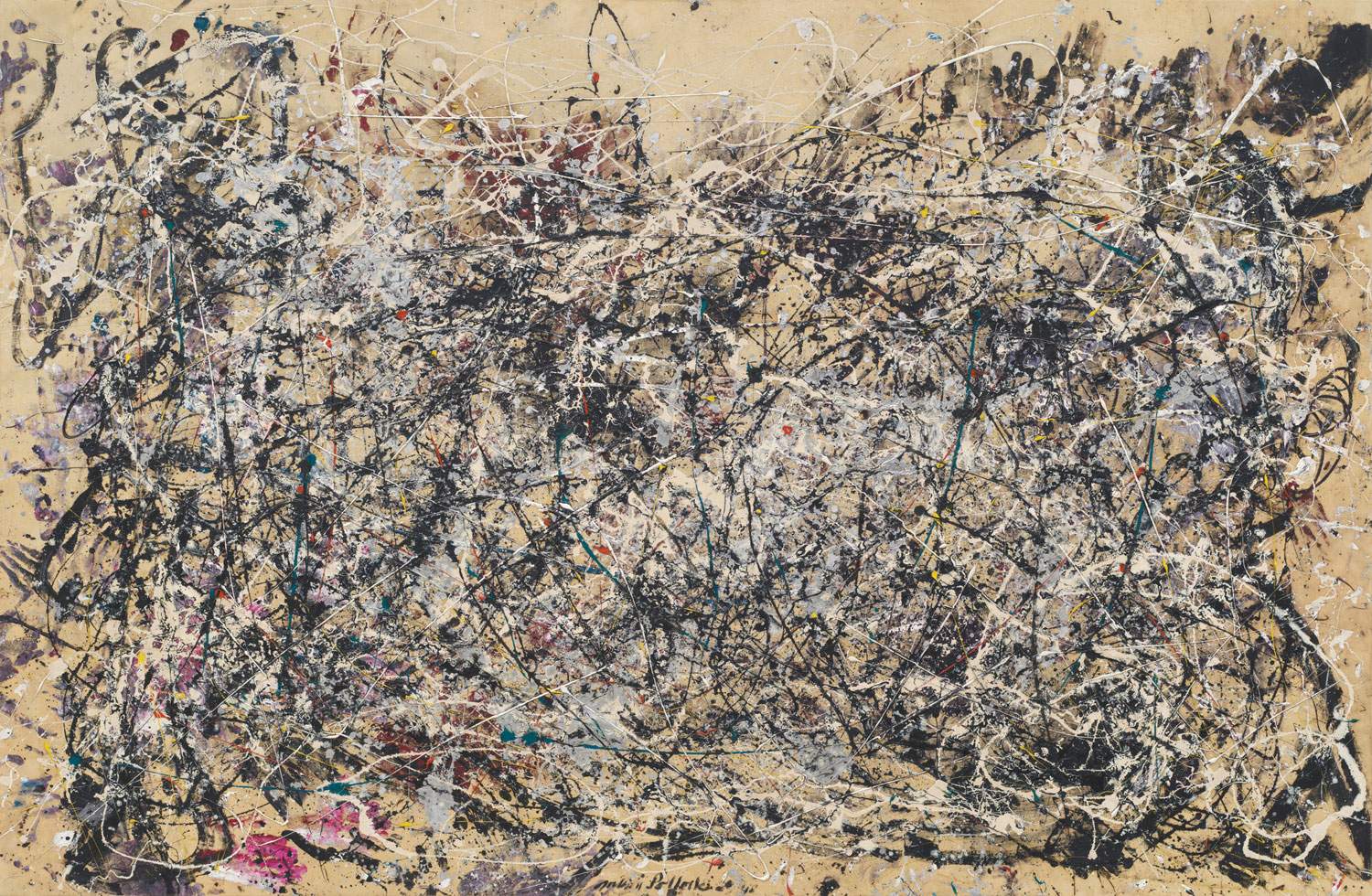

Lavander mist (1950) embodied the artistic breakthrough that the American artist achieved in the early 1950s. The work was painted near Long Island, in the studio house where he lived with his wife. For the artist to evoke such lyrical and balanced color textures was almost a ritual act, in fact, Pollock got to know the natives of his land, who considered painting a ritual. And like a native artist, Pollock signed Lavander Mist in the upper left corner: his handprints are at the top of the canvas. The allover (total, full-field) technique allowed the artist to achieve a homogeneous space, devoid of hierarchies, everything blurs together: the surface and the depth, the top and the bottom. It is legitimate to consider the relationship Pollock had with the canvas as an anticipation ofperformance, which had maximum vitality between the 1960s and 1970s. Just as in performance, expressive value in Pollock’s canvases is given by the body, mind and feelings.

|

| Jackson Pollock, Number 1 (1948; oil and paint on canvas, 172.7 x 264.2 cm; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Jackson Pollock, Lavander mist (1950; oil, enamel and aluminum on canvas, 221 x 299.7 cm; Washington, National Gallery of Art) |

Much of Jackson Pollock’s work can be seen at the Guggenheim Museum in New York(The Moon woman, 1942, and some of his most famous drippings ), Autumn Rhythm, (1950) is preserved at the Metropolitan Museum, and Lavander Mist (1950) is at the National Gallery in Washington. The National Gallery of Australia boasts one of Pollock’s most famous works, Blue Poles (1952), although the purchase of the work came amid some controversy, because the director, James Mollison, was not authorized to purchase works over $1 million, so he only obtained the painting with the approval of then Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. Italy also possesses some famous works by Pollock: in fact, at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome it is possible to see Watery Paths (1947), Painting A (1950), Square Composition (with horse) from 1937-38.

|

| Jackson Pollock, life and works of the great abstract expressionist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.