Informal Art. History, styles, artists

In the 1940s and 1950s after World War II, international art was characterized by a new aesthetic current,Art Informel, which expressed itself in various trends, mostly non-figurative, destined to influence subsequent developments in contemporary art from the 1960s to the present day. The first to study and group these trends under the expression “Art Informel” was the critic Michel Tapié (Senouillac, 1909 - Courbevoie, 1987). Informal art primarily concerned painting, whose practice, now far removed from all the patterns of the past, focused on gesture, sign and matter, put into action by the artist expressively. Through the very act of painting, it came to be more about technique, colors and materials on the canvas, and less about theory and content.

In response to the atrocities and traumas of the war, artists from Europe to the United States to Japan reacted to earlier pictorial conventions, whether to traditional naturalistic and figurative work or to the geometric style that characterized early twentieth-century Abstractionism, to embrace a new way of conceiving the painting: made without composition of forms, with novel techniques and a spontaneity and irrationality influenced by Surrealism. The road to informal outcomes had also been opened by the experiences of European Dadaism and Expressionism.

As described by Tapié this was a series of styles and artists who were not interested in being part of a movement but “in something much rarer, as authentic individuals.” Art Informel thus describes the cultural and artistic climate of mid-century international society, and brings together an interesting diversity of expressions without rules or constituted models that makes its definition broad and open-ended; it includes fromArt Brut to Material Painting, from Tachisme toLyrical Abstraction, which converged in AmericanAbstract Expressionism, to the experiments of the CoBrA and Gutai groups.

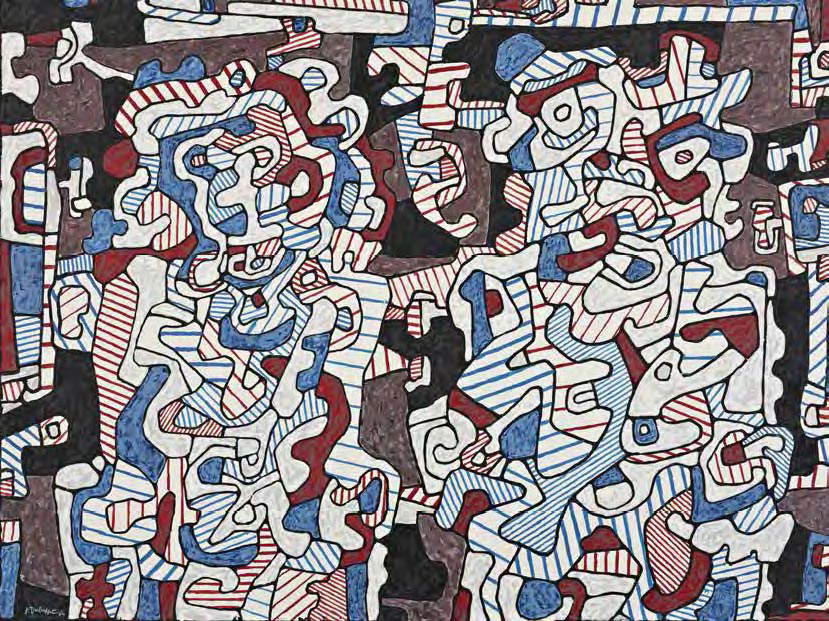

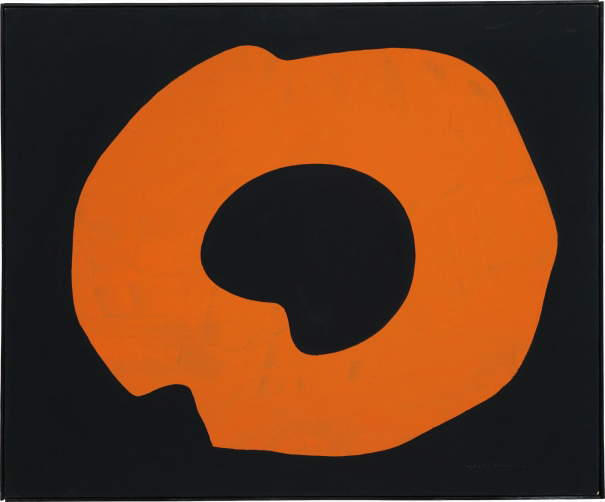

There are numerous exponents of this current who highlight its many solutions, some of the most representative: Jean Fautrier (Paris, 1898 - Châtenay-Malabry, 1964) and Jean Dubuffet (Le Havre, 1901 - Paris, 1985), Georges Mathieu (Boulogne-sur-Mer, 1921 - Boulogne-Billancourt, 2012), Hans Hartung (Leipzig, 1904 - Antibes, 1989) and Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze; Berlin, 1913 - Paris, 1951), Antoni Tàpies (Barcelona, 1923 - 2012), Asger Jorn (Vejrum, 1914 - Aarhus, 1973), Karel Appel (Amsterdam, 1921 - Zurich, 2006), Jackson Pollock (Cody, 1912 - Long Island, 1956) and Willem de Kooning (Rotterdam, 1904 - New York, 1997), the Italians Alberto Burri (Città di Castello, 1915 - Nice, 1995), Emilio Vedova (Venice, 1919 - 2006), Giuseppe Capogrossi (Rome, 1900 - Rome, 1972), among others.

Origins and Development of the Informal

Officially consecrated in Paris with the two exhibitions Vehémences confrontées and Signification de l’Informel in 1951-1952, Informal art years earlier had had its first exponents in the French artists Jean Fautrier and Jean Dubuffet and the German Hans Hofmann, who was active in the United States. Dubuffet, a promoter of Art Brut, and Tapié had met in the mid-1940s and had visited Fautrier’s Les Otages (The Hostages) exhibition together in 1945 at the Galerie René Drouin in Paris, which had fascinated the intellectual community and sparked Tapié’s involvement in promoting this new Art autre or “other” art.

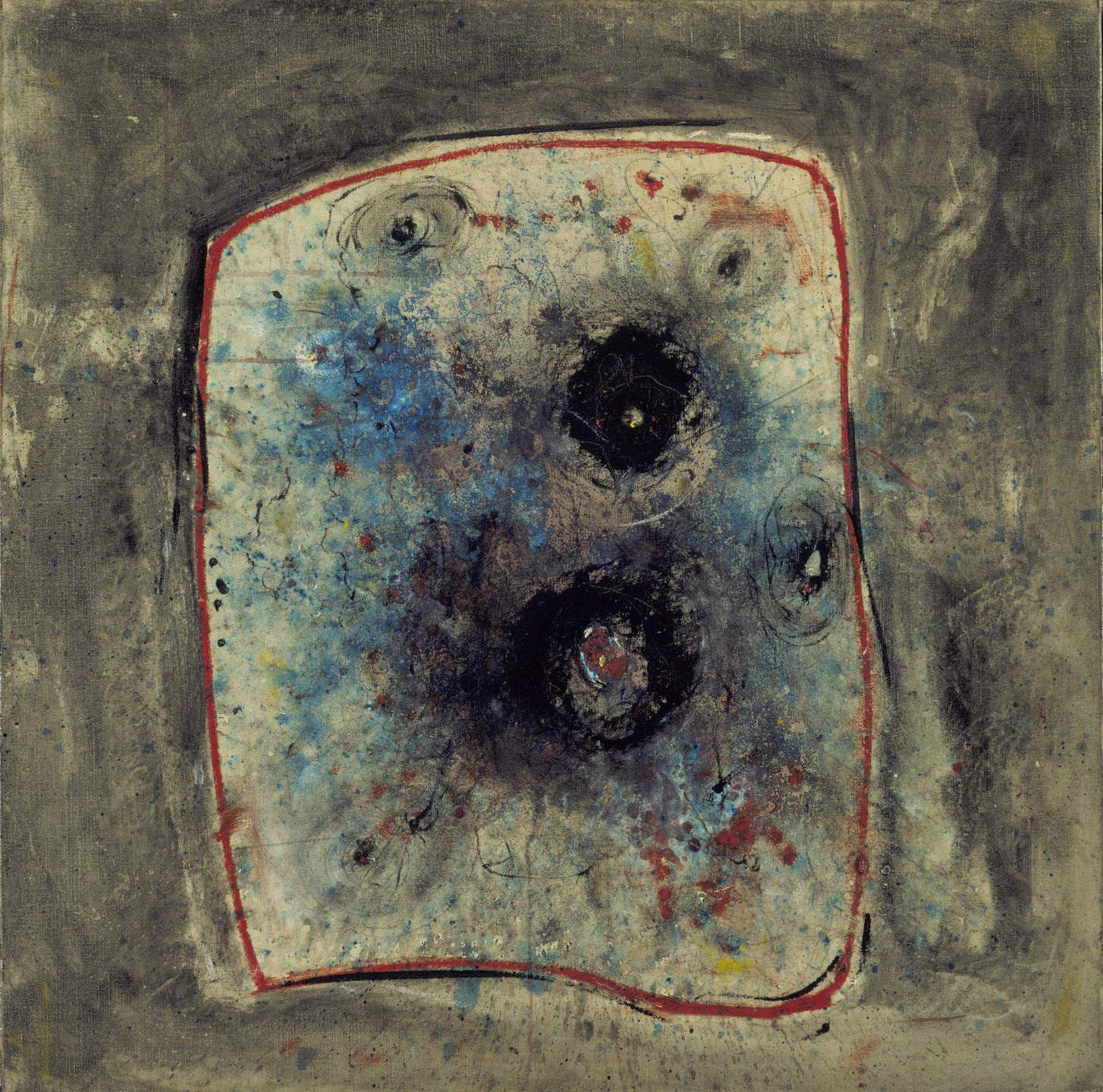

Fautrier’s works, produced in the two years before the exhibition during the war, were of a new and radical expressiveness, describing in a highly personal style the atrocities that German soldiers carried out on prisoners (hostages, precisely) in a prison yard that the artist could observe from the nearby psychiatric hospital where he had taken refuge as an anti-Nazi partisan. The politician and writer André Malraux called these works “the most beautiful war memorial of World War II.” To express his inner vision of horror, Fautrier had begun to use earthy, rough impastos on canvas, composing abstract forms with obvious gestures. These canvases embodied the principles of Art Informel, which thus interpreted the trauma and existential malaise ofpostwar Europe.

Tapié in the years to follow began curating exhibitions and catalogs, as he would do throughout his career, and in 1947 he became a consultant to the Drouin gallery while also supporting the launch of Georges Mathieu’s "AbstractionLyrique" (Lyrical Abstraction). Mathieu in turn, at that same gallery had been extremely fascinated by the works of the painter Wols, who was presenting his style known as "Tachisme," and so invited him to participate in the first of his “combat exhibitions,” by which he wanted to affirm how the new form of painting “had nothing to do with what continued to be exhibited as contemporary.” For Mathieu, works and canvases were “real battlefields” that the painter tackled “with the same impetus and eagerness as a real fight.”

Meanwhile, in 1948, Danish artist Asger Jorn organized the CoBrA group, along with Carl-Henning Pederson, Pierre Alechsinky, Corneille Beverloo, Karel Appel and writer Christian Dotremont, who gave it a name derived from the first letters of the founders’ home cities, Copenhagen-Brussels-Amsterdam. The group’s ideals emerged as a reaction to the wounds of World War II, related to “an art of immediacy,” an expression of the unconscious and childhood impulses, coinciding with the global aims of Art Informel, Many of these artists moved to Paris and met Tapié there, who, seeing their works as examples of a new and different art, began to promote their work as well.

By the early 1950s, both Dubuffet and Jorn had begun their own quest toward abstraction, aware of the overseas innovations of Americans Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and others. Thanks to Tapié, the first solo exhibition of Pollock himself was held in the Paul Fachetti Studio in Paris in 1951, and in 1952 the group exhibition “Un art autre” was held, which together with a publication of the same title, took stock of art trends in the postwar period, forming the basis of this new international aesthetic evolution. Gathered on that occasion among others were the works of French artists and CoBrA.

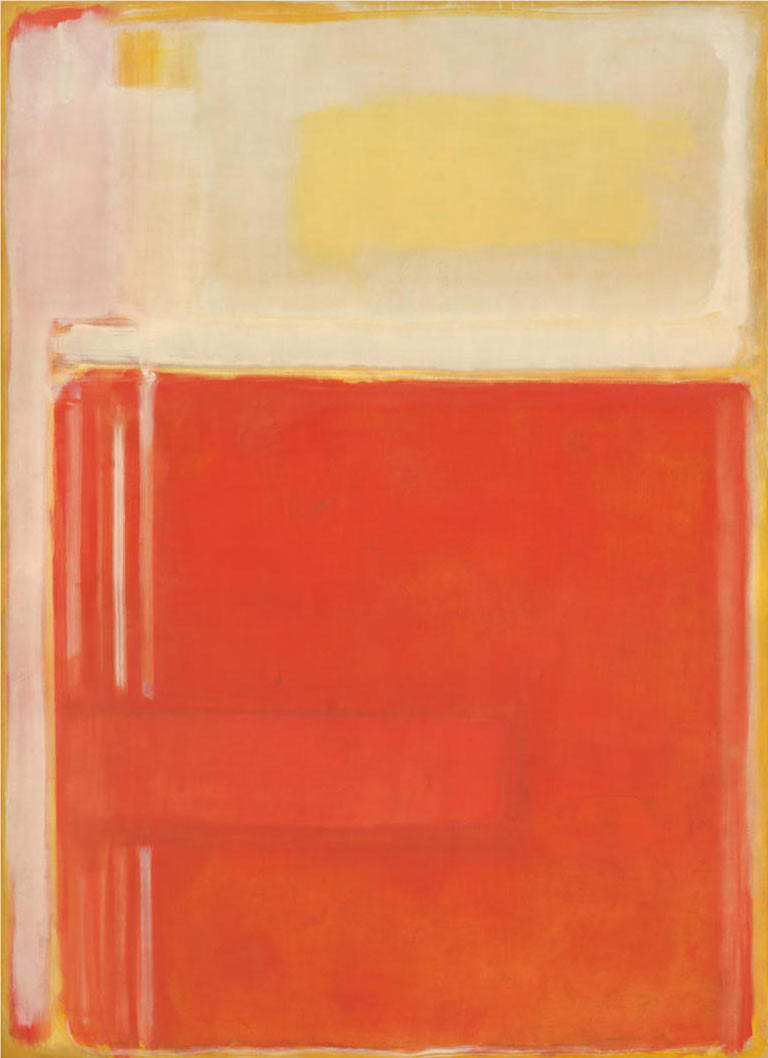

At the same time, in the United States, as mentioned above, the current of the Abstract Expressionists, a generation of artists living mostly in New York City, had emerged in the mid-1940s, followed by critics Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg who extolled the American identity of their new phenomenon of non-figurative painting. European Informal Art was soon defined in the United States as Abstract Expressionism, presenting itself in two main pictorial strands, that of "Action Painting" to which the aforementioned Pollock, de Kooning and Franz Kline, among others, worked, and "Color Field Painting" to which the works of Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still or Barnett Newman belonged.

At the same time, strongly influenced by Abstract Expressionism, the Japanese Gutai Art Association group, led by Jiro Yoshihara, was also formed in 1954, consisting of some 20 young artists from Osaka, united with their international colleagues by a desire to create new imagery in the void left by the atrocities of war and the aftermath of the atomic bomb.

Tapié at that time supported the Gutai considering their artistic proposal “free from conventional formalism, calling for something fresh and newborn,” and involved them and, beginning with the work of Jiro Yoshihara, in the exhibitions Sekai konnichi no bijutsuten (Exhibition of Contemporary World Art) in Tokyo’s Takashimaya department store in 1956-1957, which will be the first to show Informal art in Japan through seventeen works from Tapié’s personal collection, and in others in 1958, including the exhibition at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York, which was instead the group’s first outside Japan.

Meanwhile, the French critic in 1956 had landed in Turin, Italy, where he encountered the fervor of many painters, among whom significant of that season are Emilio Vedova, Giuseppe Capogrossi and the revolutionary Alberto Burri, along with many others important in Italian Informal art. Tapié chose to remain in the Piedmontese capital, and in 1959 and 1962 he organized two major exhibitions, the first “Arte Nuova” and then “Structures and Style,” with which he made a survey of European, American and Japanese painting at the end of the decade. In the early 1960s, in fact, Art Informel, when society had left the postwar period behind, was about to be overtaken by subsequent artistic thrusts in the field of painting as well, no matter how many of the adhering artists continued to produce nonetheless influential works.

While Tapié foundedICAR (International Center of Aesthetic Research) in Turin, the capital of contemporary art from Paris had become New York. At ICAR he continued to promote alongside artists such as Dubuffet, Hofmann, Tàpies, Pollock and the Gutai, works by artists from Italy and Turin in an important dialogue of international exchange. Tapié was responsible for the international notoriety of such innovative artists as Lucio Fontana.

Styles and Trends in Informal Painting

As mentioned, the Informal was not a homogeneous artistic movement and presented even opposing trends, since each artist expressed himself in the freest, most spontaneous and expressive way possible for himself. It was a path that in the postwar period determined that art should start again from the individual, from the author’s unique relationship with his work, shared by the writers and intellectuals of the philosophical current of EuropeanExistentialism. Despite stylistic differences, the many artists addressed the themes of war, suffering and trauma, irrationality and freedom, in an attempt to come to terms with historical events and reinvent a new way forward, to shape a new society.

In the painting that has become “informal” without recognizable figures, without perspective or geometry, at least three currents can be identified that have the main protagonists in common: gestural, sign and material Informal. The first, an action painting for which the work corresponds to the act of painting itself and goes beyond the executed painting, where the color is given to the canvas with instinctive, non-canonical gestures and with the artist in movement with respect to the support; in all its declinations, it is largely based on the abstraction of gestures that often contained personal stories and different intentions. From the existential explorations of the American Abstract Expressionists to the “fights” of Georges Mathieu or the drawings of Asger Jorn, however gestural painting allowed artists to embrace spontaneity. The gestural group has as its American protagonist Jackson Pollock and his " dripping " technique, that is, the dripping of color onto large canvases spread out beneath him who was, like others, at work standing up. In Europe, a leading artist was Wols, the principal pioneer of Tachisme, from tache meaning stain, whose painting was based on spreading color in patches, employing pigment directly from the tube. Wols had created his own pictorial language by using paint in innovative and nontraditional ways, “thin glazes of color, crust-like slurries, splashed and poured pigments, direct rivulets of liquid paint, scraped edges, back scratches and brush lettering, even marks made with the circular mouths of paint tubes.” Often compared to Jackson Pollock, Wols’ paintings were smaller and more controlled than Pollock’s drip paintings.

Of the Cobras, along with Jorn, Karel Appel’s handling of painting suggests the fundamental characteristic of this Informal approach, spontaneity as in the drawings of children, the mentally ill and folk art, a colorful expression of emotional intensity.

Among the many artists of the gestural Informal was the Italian Emilio Vedova, who painted almost violently on vast assembled surfaces.

Still other artists use recurring motifs and marks as opposed to drips or blotches as recognizable graphic elements but without specific meanings, creating new indecipherable, nonconceptual visual alphabets in which the calligraphic component is evident. A writing on the canvas as on an unconventional sheet of paper with touches of color or ink.

Among the most significant artists of sign painting we find Wols, along with Georges Mathieu, one of the most famous and successful painters in France who pioneered Lyrical Abstraction, and again Hans Hartung and among many others the Italian Giuseppe Capogrossi.

Mathieu’scalligraphic approach set the school, and his emphasis on rapid execution was a way to connect with immediate intuitive expression: no pre-existing form or reference, unplanned movement by the artist, almost in a state of ecstasy: loose painting with a “lyrical” effect, often using rich colors, evoking the natural world and a kind of balance in the images created.

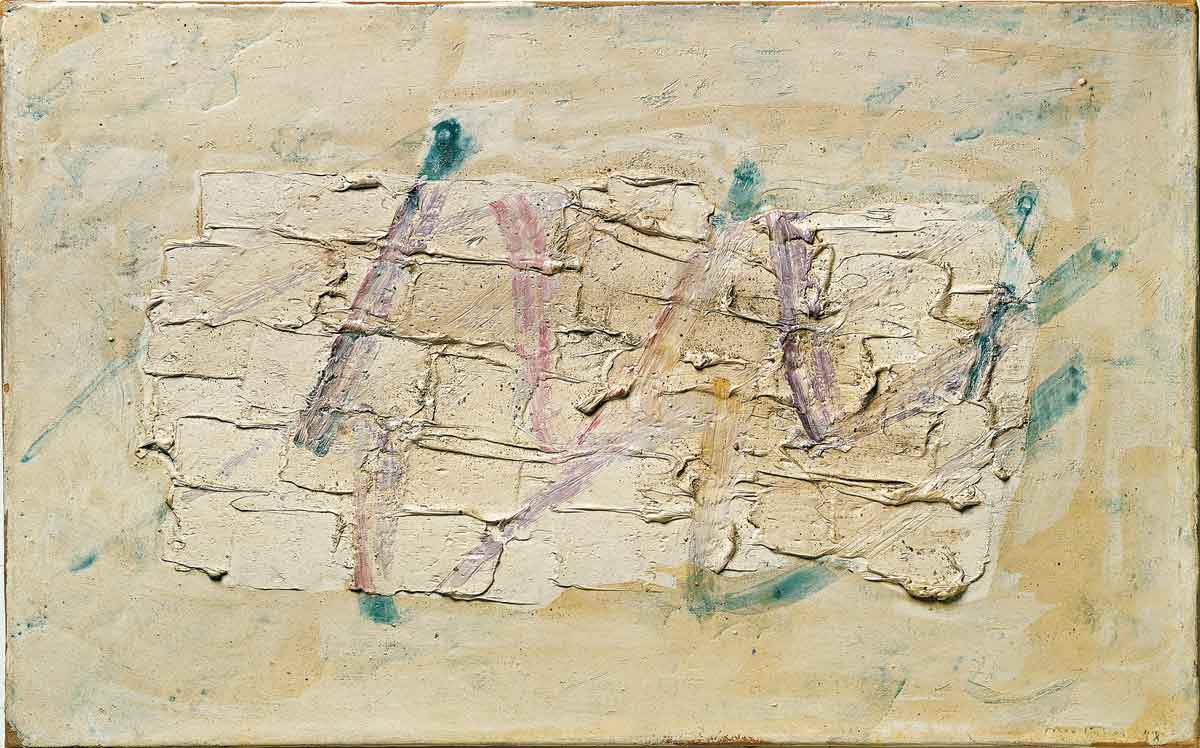

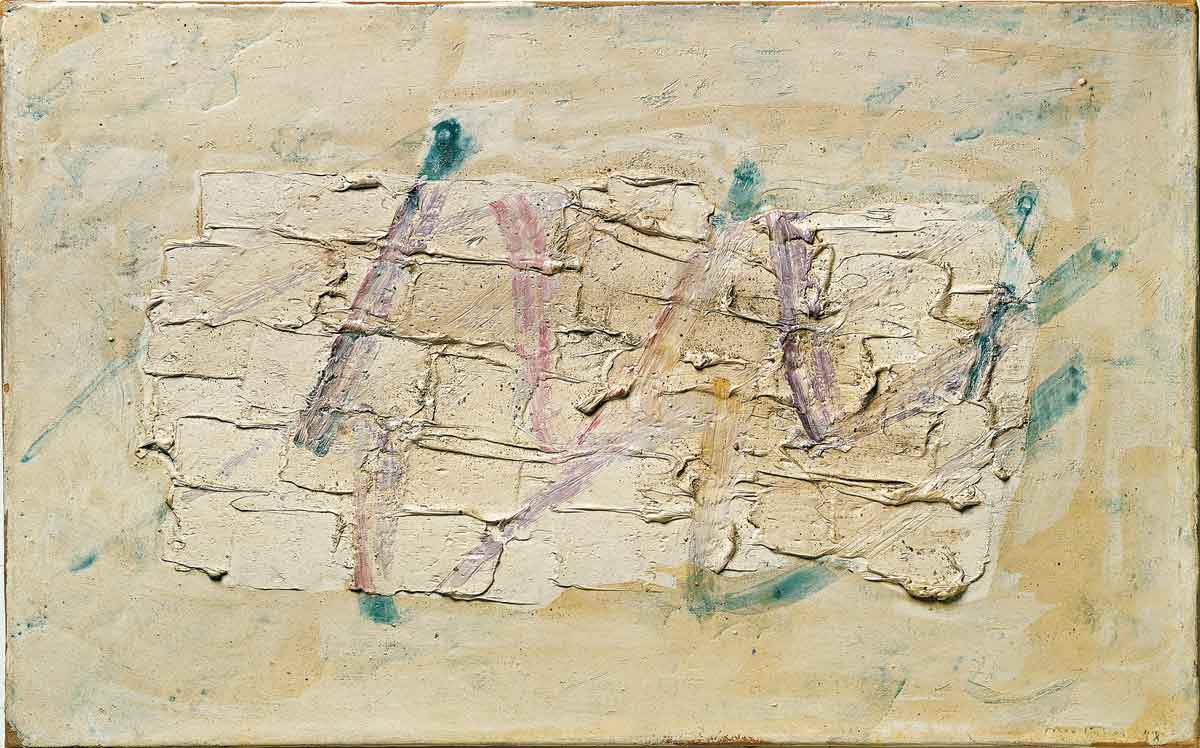

Material painting , on the other hand, and this is the trend that is most evident in Europe, is executed from color with heterogeneous and unusual materials, from particular impastos to real three-dimensional inserts, available to the artist at the given moment of creation.

The real change that the matter painters brought about was to go beyond form by applying, as had not been done before them, from poor materials such as powders and sand, stones, newsprint and cloth or glass, to others innovative for their time, such as plastics.

Matiérisme or Matter painting had taken hold in the early 1940s and had among its great interpreters Jean Dubufett who, following the example of Fautrier’s thickly painted surfaces, worked on "haute pates" or raised pastes, as he used a thick paste into which he mixed a variety of things, including earths and cement or asphalt. With this technique, the flat canvas had been transformed into a tactile raised surface that extends into space.

In this vein worked the Spaniard Antoni Tàpies and in Italy, in particular, Alberto Burri, who began painting during World War II with makeshift tools in a Texas prison camp and then established himself, leaving brushes aside, with paintings made of hemp sacks showing rips, seams, patches, burns, and from the juxtaposition of what he also collected among the garbage. “If I don’t have one material, I use another,” asserted the artist, who incorporated in his compositions from burned woods to sheet metal to plastic. For works thus no longer classifiable in the traditional categories of painting or sculpture.

|

| Informal Art. History, styles, artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.