The mature Renaissance in Rome, between Michelangelo, Raphael and Sebastiano del Piombo

In the early sixteenth century, Rome and the Papal States reached their apotheosis both as the needle of the scales in the political interests of Italy and as a center of artistic production, because many of the greatest artists working in the early sixteenth century came to Rome. This role of Rome obtained considerable impetus under the pontificate of Giuliano della Rovere, who, elected to the throne of Peter under the name of Julius II in 1503 after the very brief pontificate (less than a month) of Pius III, wanted to assert decisively not only the spiritual role of the Church but also the temporal one: he was in fact a promoter of a league of states that could counter Venetian expansionism (Rome and Venice were bitter enemies throughout the sixteenth century), except later agreeing with Venice to wage war against Ferrara, an ally of the French who posed one of the greatest risks to the stability of the Italian states.

These are the assumptions that explain why Julius II was one of the greatest patrons of the time: art for Julius II played an ideological role in that the works he commissioned were endowed with iconographic programs intended to convey symbolic values (for example, his funeral monument, commissioned from Michelangelo, was meant to represent the pope’s role as the leader of Christianity), and because art was for him a means of demonstrating to the world the power of his Rome. Julius II also reordered the urban aspect of Rome according to the canons ofRenaissance architecture and commissioned artists to devise plans for the reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica, which was to become the greatest temple of Christendom. The ideological intent of Julius II was, in fact, to justify the temporal power of the Papal States on spiritual grounds.

Michelangelo in Rome

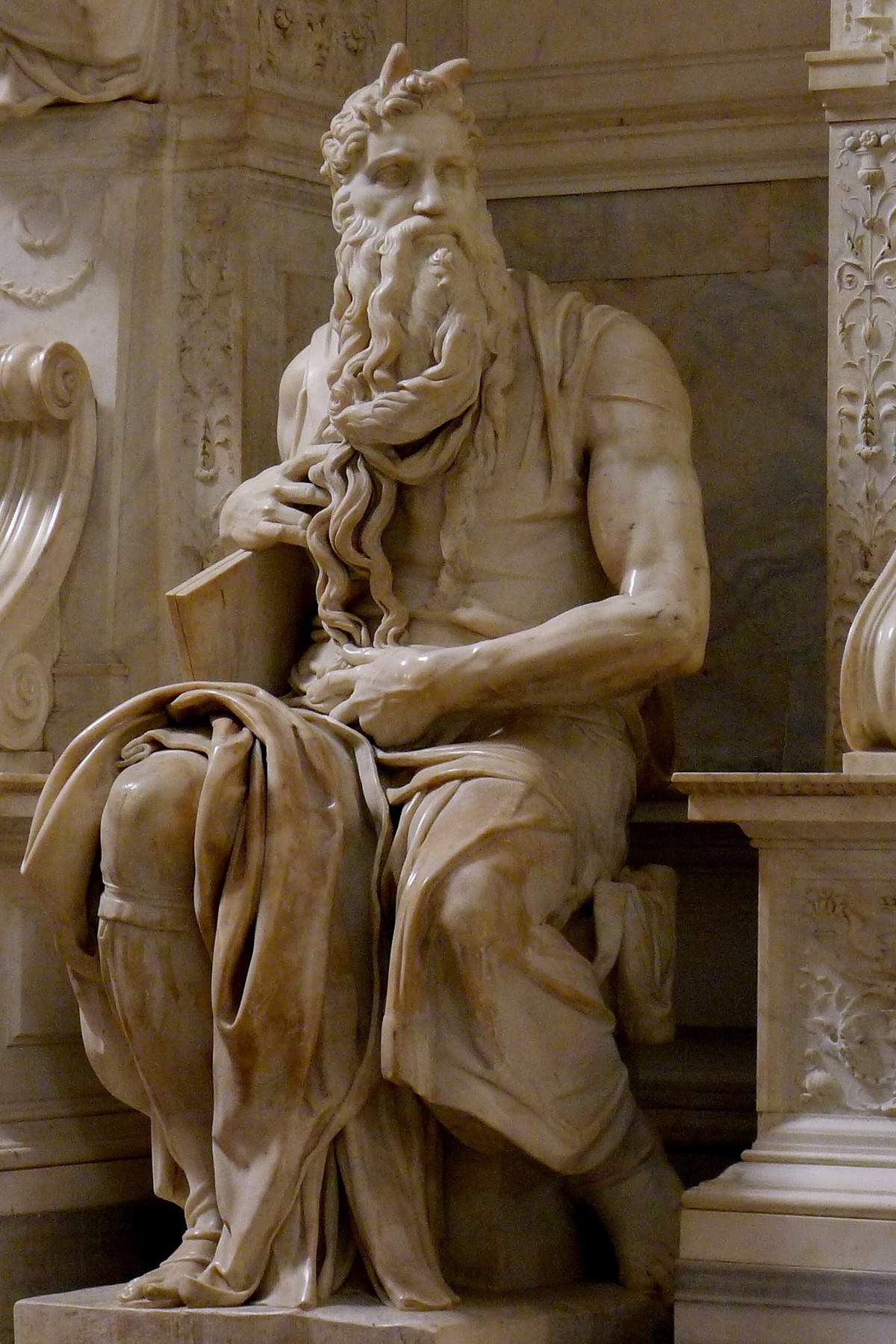

The first artist called to Rome by Julius II was Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564): his first assignment was to design the pontiff’s funeral monument. This important monument revisited the traditional type of the funerary monument in a more monumental way, with a scheme that was completely innovative and unknown to contemporary art, but above all it included a mixture of Christian and pagan elements that made explicit a trend in the art of the time, according to the popes’ intentions, namely that of imbuing elements typical of classical antiquity with Christian significance: already Alexander VI in fact had used elements drawn from the pagan repertoire (in his Borgia Apartment frescoed by Pinturicchio) bending them to the needs of Christian spirituality and thus investing them with a new meaning. The statues that are (and were to be) part of the work are all almost marked by Michelangelo’s unfinishedness and reveal that tension and drama that indicate once again the philosophy underlying Michelangelo’s work, that of man’s struggle to reach his goal.

The revisitation of the founding canons of the early Renaissance reaches its zenith in the frescoes that decorate the vault of the Sistine Chapel: the linear perspective of the Renaissance is abandoned altogether, and in its place Michelangelo foregrounds, as a sculptor, the figure of the individual character, marked by strongly energetic and vigorous features that are precisely typical of the work of a sculptor, as well as the charge of tension that distinguished his earlier achievements. This incredible and powerful mixture of classical and Christian elements, treated with his dramatic impetus, shocked his contemporaries in a positive sense: the work received unanimous approval, even from his rival Raphael Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520).

Raphael in Rome

Raphael, who arrived in Rome in 1508, was commissioned by Julius II to decorate all the pontiff’s apartments with frescoes: this was the first major public commission by the young Urbino, then just 25 years old. Raphael gives evidence of mastering one of the cornerstone principles of the mature Renaissance, monumentality, here aimed at representing, in a solemn and official way, the grandeur of the church. For this he drew extensively from the classical repertoire as evidenced by a fresco such as the School of Athens, with the balanced gathering of all the major philosophers of antiquity (who for the occasion took on the guise of contemporary artists and intellectuals). In fact, the iconographic program of the Stanza della Segnatura (where the School of Athens is located) was intended to exalt the humanistic culture of the papal court by representing, on the four walls, the allegories of the four disciplines that constituted, precisely, the foundations of humanistic culture: theology, philosophy, poetry and justice, which in turn became symbols of four different qualities taken from Neoplatonic philosophy, namely rational truth (philosophy), divine truth (theology), the beautiful (poetry) and the good (justice). With Raphael, Julius II’s ideological wishes reach their ultimate fulfillment.

Beginning, however, with the second of the Vatican Stanze assigned to Raphael, the young Urbino demonstrates that he is partly abandoning the grace that had marked his production up to that point in order to move toward more dramatic representations, and ones that also welcome Michelangelo’s plasticism. This tension underlies the Stanza di Eliodoro, where Raphaelesque art begins to set aside the ideal and almost abstract beauty that had distinguished it to embrace instead a style that could provoke more of the viewer³’s emotional involvement. We find such tendencies again in the Stanza dell\’Incendio di Borgo (made under the pontificate of the new pope, Leo X, born Giovanni de\’ Medici): here Raphael too, as well as Leonardo and Michelangelo, arrives at the abandonment of linear perspective. This new style made of reflections on Michelangelo’s plasticism, emotional involvement and rejection of order will find its highest expression in the Transfiguration (1518-1520, Rome, Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana), Raphael’s last masterpiece, marked by a dramatic quality that anticipates many of the outcomes of later art.

Sebastiano del Piombo

The Transfiguration was painted by Raphael in open competition with Sebastiano Luciani, known as Sebastiano del Piombo (Venice, 1485 - Rome, 1547), the third leading figure of the mature Renaissance in Rome, who was a friend of Michelangelo and rival of Raphael. In 1517, in fact, Cardinal Giulio de\’ Medici (future Pope Clement VII) commissioned two works from the two artists for the cathedral of Narbonne in France, the city of which he was bishop: Raphael did the Transfiguration, while Sebastiano del Piombo did the Resurrection of Lazarus (1517-1519, London, National Gallery), and the work took a long time because neither rival wanted to finish first. What Sebastiano produced was an excited scene that echoed Michelangelo’s precedents, visible not only in the dramatic charge but also in the vivid colors and plasticism of several figures.

Already in Venice (Sebastiano del Piombo was in fact a native of Venice), the painter had revisited the local artistic tradition by blending the typically Venetian predilection for color with a quest for grandeur and monumentality. However, in the end (given also the competition with Titian, a struggle that was already lost at the start) the artist had to move to Rome, where an art like his could find greater appreciation from patrons. Sebastiano del Piombo was in fact among the few artists who managed to reconcile Venetian atmospheres with an \art of Tuscan ancestry, which in this case, could only look to Michelangelo, given Sebastiano del Piombo’s natural predisposition for monumental works and given hisfriendship with the great artist from Caprese (Death of Adonis, c. 1512, Florence, Uffizi). Sebastiano del Piombo also used Venetian atmospheres to instill a sense of greater religiosity inhis works (the landscapes in fact accentuated this sense: this is the case, for example, of the <emPietà , 1512-1516, Viterbo, Museo Civico, where even the darkness enveloping the two monumental figures of the Madonna and Christ seems to want to induce the viewer to reflect on the death of Christ: read a more in-depth discussion here), in line with the requests of the patrons: Sebastiano del Piombo was an important member of the papal court as he obtained in 1531, from Clement VII, the position of piombatore, a sort of secretary of state.

|

| The mature Renaissance in Rome, between Michelangelo, Raphael and Sebastiano del Piombo |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.