Happening and Fluxus. Origins, history, style, main exponents

In post-World War IIEurope, the memory of the tragedies derived from the war event and the political tensions caused by the Cold War led to the creation of various opinion movements that opposed all forms of authoritarianism. This led the artists’ researches toward a reflection on the human being, seeking alternative expressions to the artistic experiences of theInformal, which was marking the cultural scene of those same years.

The artistic experiments that occurred between the 1960s and 1970s are gathered under the label of Neoavantgardes, as they were in line with the conception expressed by the historical Avant-gardes of the early 20th century, in the wake of what was indicated by Marcel Duchamp, who saw art as a purely mental process and redefined the conception of the work of art. New Dada, Body Art, Land Art, the Happenings and Fluxus were all trends that set out to investigate the question of art in relation to life and society, thus the attached problems of a political and social nature, telling them in ways most congenial to their artistic nature.

In particular, the movements that swept through Europe beginning in 1968 gave rise to a series of changes in the conception of individual rights and freedoms, sexual attitudes. There grew media and societal attention to the body: artists explored this theme by bringing the body to act in a performative dimension. Here the evidentiary component of the specific photographic and video recording proved crucial.

Many artists, even conceptually distant from each other, followed this research: in France, Yves Klein with Anthropométrie (1960); in 1961, in Italy, Piero Manzoni left his signature on a model, creating Scultura vivente . At a time when the body was rising to a pivotal theme in international artistic research, the Japanese Gutai group, the Viennese Actionists, Allan Kaprow with the Happening and Fluxus outlined a new expressive horizon in contemporary art.

Origin and development ofHappenings and Fluxus

Between the 1960s and 1970s profound social transformations and new political arrangements affected Europe and the United States. 1968 was a crucial year that saw the most radical changes, especially in Europe, where there was the politicization of large segments of the youth and student population that moved against institutions and bourgeois morality, in opposition to consumerist society and the capitalist economic system; they were movements of denunciation against all kinds of authoritarianism.

These strong currents spread in pursuit of the redefinition of political arrangements, cultural and social rethinking, arriving at the women’s emancipation movement, claims in the areas of individual freedoms, human and bodily rights, and sexual orientations. These were scenarios that inevitably spilled over into the world of art and culture, where more canonical patterns were challenged. These were proposals already timidly advanced in Surrealist and Dada circles, in the early 20th century Avant-gardes. The artist Marcel Duchamp already pursued the idea of an art that was more conceptual, with a view to overcoming - with his ready-mades - the convention of the work of art understood as an aesthetic artifact offered to passive contemplation.

Some anticipations of this perception of art making also appeared in choreographer Merce Cunningham ’s modern ballet and John Cage ’s experimental music in America in the 1950s. At a moment in history when the individual was placed at the center of a rethinking in an existentialist key, there emerged a new consideration of the audience and the user of the work of art, who began here to emerge from his passive role where he had hitherto been relegated, becoming an essential component of the work itself.

The accomplishment of this disruptive transformation in the artist-user relationship is due to the naturalized Russian artist from the United States, Allan Kaprow (Atlantic City, 1927 - Encinitas, 2006): he was the creator of a new form of expression, to which he gave the name happening (event, happening). Kaprow carried out many of these artistic events in the United States and abroad, going systematizing certain trends and organizing them from the Duchampian concept that “life itself is art.” He also shared the idea of art as the “action of life” with the musician John Cage, with whom he was close friends. At an early stage, the happenings were related to the dimension of music, theater and modern ballet, so much so that the first events took place in dance schools or small experimental theaters.

Also from the Japanese front, the Gutai group was an experience that experimented with evenings on stages, with artists engaged in actions and performances, somewhat precursor to Kaprow’s happenings. In 1957, French critic Michel Tapié traveled to Osaka, where he supported the group, promoting its events in American exhibitions as well. Thehappening proper was born, however, in 1959, when Allan Kaprow organized an intervention at the Reuben Gallery in New York: 18 happenings in 6 parts.

Although the work-event originates as a project, the result in its future is absolutely unpredictable given the necessary involvement of the audience. This artistic mode established a new mode of dialogue with its viewers, who were involved in an exchange of psychological energies. The total unpredictability of the outcome was considered part of the artistic project, which had no script or scenic narrative apparatus. Hence the happening distanced itself from an “architected” environment such as the theater to structure itself in the systematic use of themost everyday environment, such as the street, where it took in active participation anyone who was actively on the scene. Kaprow thus consolidated that thought, embryonic in the early twentieth century, that every moment of life is potentially a work of art: to make it so, it must be understood in its potential artistic dimension, separating it from the ephemeral of the everyday. And it is essential that the event arise spontaneously. Kaprow structured his thinking in the text Assemblage, environments & happenings (1966), which opens as follows, "The line between art and life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible." That thought, which supported the implementation of the happenings, provided fertile ground for the birth of Fluxus.

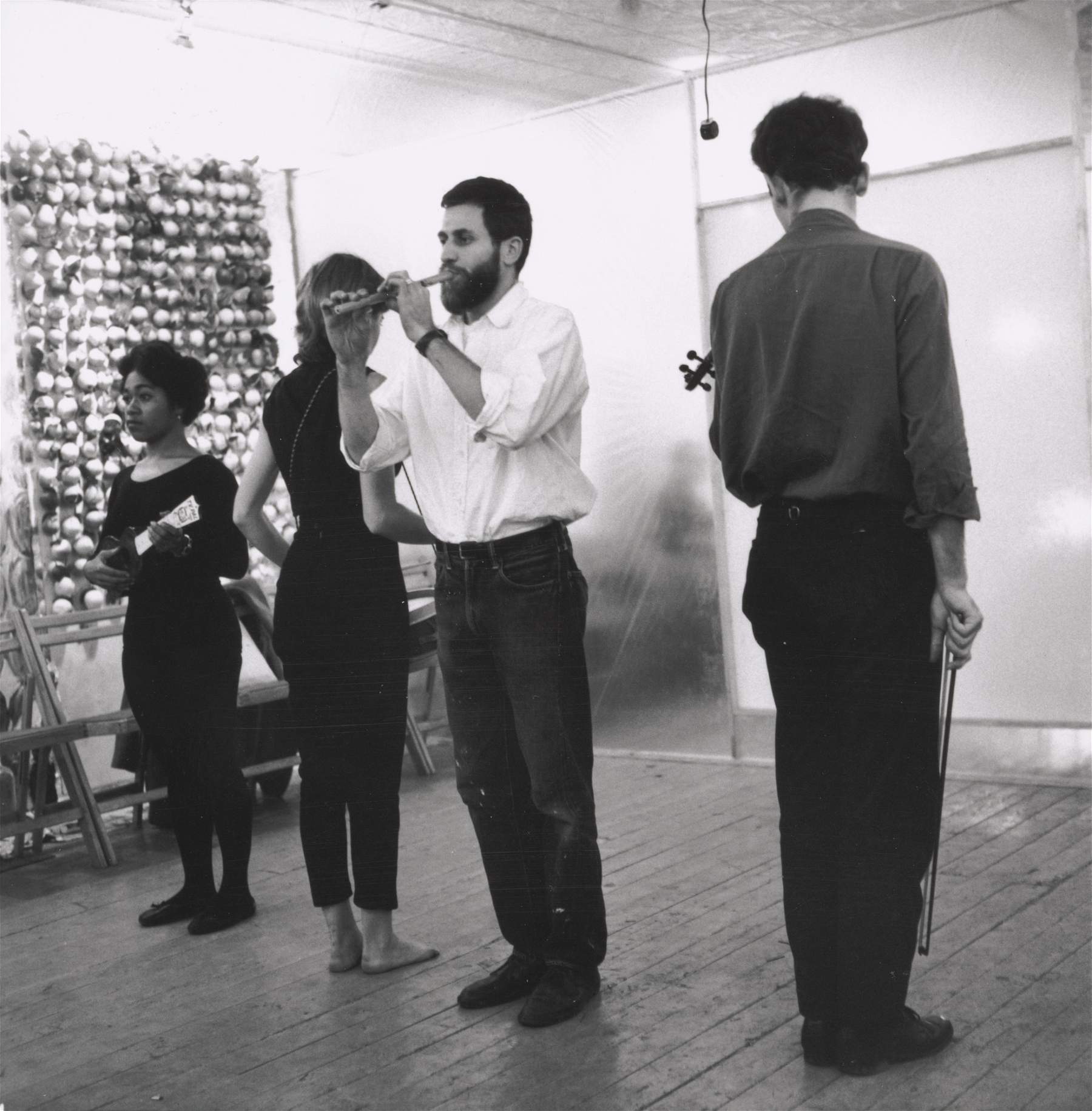

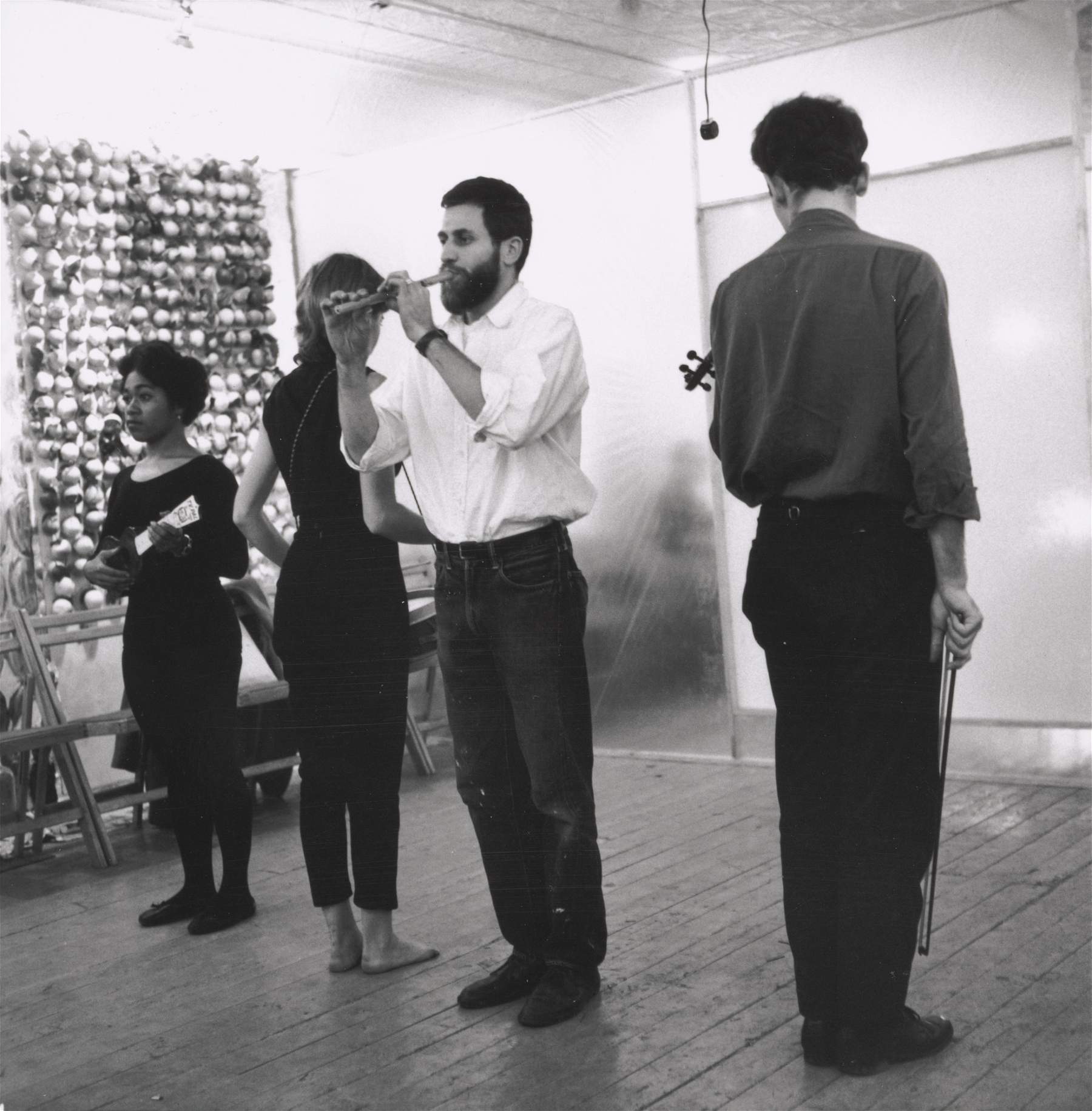

Fluxus was a group that emerged between 1961 and 1962 in Europe: initially its constitution was derived from the field of music, particularly experimental concerts. Lithuanian artist and architect George Maciunas (Jurgis Mačiunas; Kaunas, 1931 - Boston, 78), considered one of the founders of the group, promoted the first Fluxus events in New York in 1961, at the experimental concert Musica antiqua et nova, and then in Germany, in Wiesbaden.

Fluxus was a somewhat interdisciplinary phenomenon, which is why it is difficult to reconstruct or define: it cannot be called a movement, since it lacked an internal poetic organization. The common denominator was the belief that everything could be art and that anyone could practice it: once again, every moment of life can be an artistic event, if thought of as such and exposed to the user, who is involved along with his or her reactions. Fluxus was also the natural outcome determined by all those social and political movements that shook Europe in those years, so it was an experience characterized by the maximum democratization of art. In fact, all contributions were accepted: the group thought of the artistic event as an uninterrupted flow of situations and emotions; every participation was considered fundamental regardless of origin. From the experimental sphere of musician John Cage, to the participation of land-artist Christo, Daniel Spoerri from Nouveau Réalisme, Joseph Beuys from the German poverist sphere, to the performances of Japanese artist Yoko Ono.

Fluxus followed the principle of diffuse creativity, as the artists, each bringing their own training and experience, crossed the boundaries between visual art, music, poetry and theater, and every other discipline. At the same time, they attacked the figure of the professional artist and the art system, challenging the elitist market, advocating instead an art accessible to all. All this by transforming the irrelevance, the banality of everyday actions and objects through an aesthetic reinterpretation.

Major exponents and styles

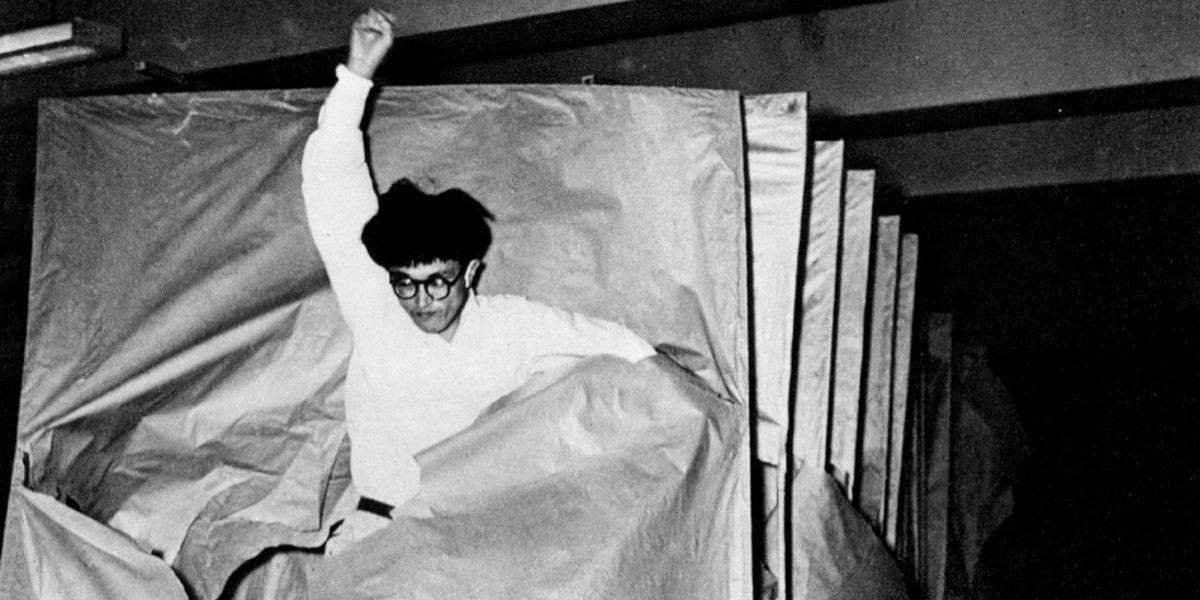

From Japan, Gutai artists organized various events in both indoor settings, such as galleries, and outdoor or stage exhibitions. In 1955, at a first group show of the group in a Tokyo gallery, the artist Saburō Murakami (Kobe, 1925 - Kyoto, 1996) violently threw himself at a series of paper screens, ripping open the surface with his own body: the work-action took the name Making Many Holes in an Instant. During the same occasion, in the garden attached to the same gallery, thus in the open air, Kazuo Shiraga (Amagasaki, 1924 - 2008) rolled so vehemently in a muddy puddle that he sustained small wounds. The performance, punctually photographed, was called Challenge with Mud.

A few years later, in 1959, Allan Kaprow (1927-2006) studied the work for which happenings can be spoken. 18 Happenings in 6 parts: six series of actions took place simultaneously in three different rooms of the Reuben Gallery, New York. Various everyday objects and some musical instruments were scattered in these spaces. Viewers were invited to use them according to instructions provided by the artist himself, creating an effect that was nonetheless outside of design predictability. In 1961, for the Collective Martha Jackson Gallery NY 1961, again Kaprow filled the courtyard behind the gallery with hundreds of used tires and invited viewers to walk across, sit and lie on these tire piles, even moving them at will and then repositioning them in place. The happening was called Yard.

For Kaprow, it was essential that viewers participate in the event with an almost childlike spontaneity; they had to be willing to play with the artist without asking too many questions. Yard was a crucial work in the artist’s production, ironically and unscrupulously utilizing an exhibition space, using tires as a metaphor for the pollution of the art world.

Beginning in 1962, the German Joseph Beuys (Krefeld, 1921 - Düsseldorf, 1986) forged contacts with the Fluxus milieu: in this context he contributed with the realization of Homogeneous Infiltration in 1966, covering a grand piano with a cloth, now preserved in Paris at the Centre Pompidou.

Frenchman Ben Vautier (Naples, 1935) deserves special attention for his production made up of gestures and provocative stances, precursors to the climate of 1968. Attributable to the Fluxus group, Vautier in 1963 brushed his teeth in public, a banal act performed on any street in Nice. An event considered artistic the moment it was proposed to an audience and immortalized in a photo, Se laver les dents en publique.

To the 1970s dates the performance Tv Cello (1971): in this case, television sets introduced into the assemblages were used. The idea was by Nam June Paik, a Korean artist (Seoul, 1932 - Miami, 2006), forerunner of what later became video art. It involved a bizarre structure that replicated the likeness of a cello: small monitors transmitting sound and images were embedded inside. In the performance, the instrument was played by an American musician and performer, Charlotte Moorman (Little Rock, 1933 - 91). Sounds and images were transmitted by cable and as such were completely unpredictable, combined with the actual sounds emitted by the concert performer’s action.

|

| Happening and Fluxus. Origins, history, style, main exponents |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.