Gustave Courbet, life, works and style of the father of realism

Gustave Courbet (Ornans, 1819 - La Tour-de-Peilz, 1877) is considered l father of realism, an artistic movement to which he devoted his activity between 1848 and 1855. The second half of the nineteenth century was a very important historical moment for Europe: starting with the revolutionary uprisings of 1848, a period of great political tension began. In this scenario, the realist movement consolidated around 1850 and prevailed until 1870-80: it had its most coherent formulation in France. It was a new artistic current in response to a more conservative, academic-style classicism.

Realism intended to tell the truth of its time, offering a faithful and objective, deliberately unpolished representation of everyday life. Courbet was the most important interpreter of this movement: drawing his subjects from everyday reality, he recounted contemporaneity with great awareness. His was an active painting, committed to objectively recounting everyday life and denouncing the injustices of simpler city life. In his late activity he also devoted himself to landscape painting, as if anticipating the Impressionist experiences that would be formed a few years later, in the 1870s.

But the paintings for which he is remembered as the greatest exponent of the new realist movement are those in which he inserted the most common subjects, replacing the idealized characters dear to classicism. Fellow citizens of Ornans, hunters, peasants: Courbet expresses their labors and publicly condemns the circumstances of the period in which they live. His art, then, is great not only as a witness to an intense historical moment for Europe, but because he engaged in an active, meaningful narrative that had the power to stimulate a response in the public. A living art that acted alongside workers and revolutionaries. Moreover, Courbet’s ideas increasingly took on a well-defined political physiognomy, which led him to side with the proletariat, in anti-capitalist positions. In fact, the political experiences concentrated in the final stages of his life led him toward exile: accused of collaborationism with the revolutionary government, excluded from the 1872 Salon, Courbet opted to leave France. He found his refuge in Switzerland, where he spent his last days. The eloquence of his art was still very effective and later contributed to the formation of the great names of Impressionism and the painters still to follow.

Gustave Courbet was undoubtedly a pioneer of the radical change in values that realism provoked around the middle of the nineteenth century. This role was acknowledged to him by Guillaume Apollinaire in 1912, when in his meditations around the Cubist painters he unreservedly proclaimed that “Courbet is the father of the new painters”; and it is a paternity that is still easy to recognize in front of his works today.

Life of Gustave Courbet

Gustave Courbet was born in Ornans, in the eastern region of Franche-Comté, on June 10, 1819. His was a wealthy family, his father a landowner. He had a peaceful childhood, growing up among his beloved sisters and surrounded by beautiful landscapes that helped create in him a keen sensitivity to nature. His education was uneventful: in 1837 he moved to Besançon, where he began his first pictorial studies and looked in all likelihood to the earlier Romantic masters. The French capital soon exerted an attraction on him, who had a curious and lively temperament.

He moved to Paris in 1840 and here frequented many intellectuals, becoming friends with the poet Charles Baudelaire and the critic Jules Champfleury. He also openly supported the anarchist philosopher Pierre Joseph Proudhon. He was a frequent visitor to beerhouses and taverns, especially the famous Andler brasserie in Paris, where the painter met with friends and those intellectuals together with whom he would later give a more consistent structure to the emerging realism. As one of his earliest works,Self-Portrait with a Pipe (1847), shows, Courbet chose a bohemian life, avoiding fitting into the French academic context, which was too narrow for him and certainly far removed from the reality he felt he wanted to represent.

Courbet cannot be said to have had a real master: he learned to paint by observing reality up close, frequenting the halls of the Louvre where he copied Caravaggio, Flemish paintings, studied the Venetians and the Dutch of the seventeenth century, and was inspired by the Spaniards Velazquez and Murillo. Life in the French capital was very stimulating for a man like Courbet: it was a time of strong growth, both economic and industrial, fostered moreover by new discoveries and inventions. The uprisings of 1848 marked the beginning of a revolutionary wave that subverted the political order of Europe. At such a dense and highly tense moment in history, Courbet was struck by the ideals of ’48 but had not yet developed a full, burning political consciousness. Therefore, he did not actively participate in the demonstrations but remained more on the sidelines, occupying a spectator position. He would become more active very few years later, in a way that was more congenial to him: after all, the uprisings of ’48 had shaken other registers as well, including the one governing the relationship between society and artistic research.

The horizons of the capital helped expand Courbet’s vision, but he always remained very attached to Ornans, his hometown, where he always returned to paint, rediscovering his roots and his family. He continued to seek financial support from his parents, even though he had begun his painting activities some time ago; the anti-academic sentiments that characterized his production caused him serious difficulties in the Parisian artistic milieu, and the economic negotiations he carried out were initially poor. Thanks to family support he was able to travel: in the fall of 1847 he went to Holland and then to Belgium, places where he had the opportunity to deepen his interest related to Flemish painting.

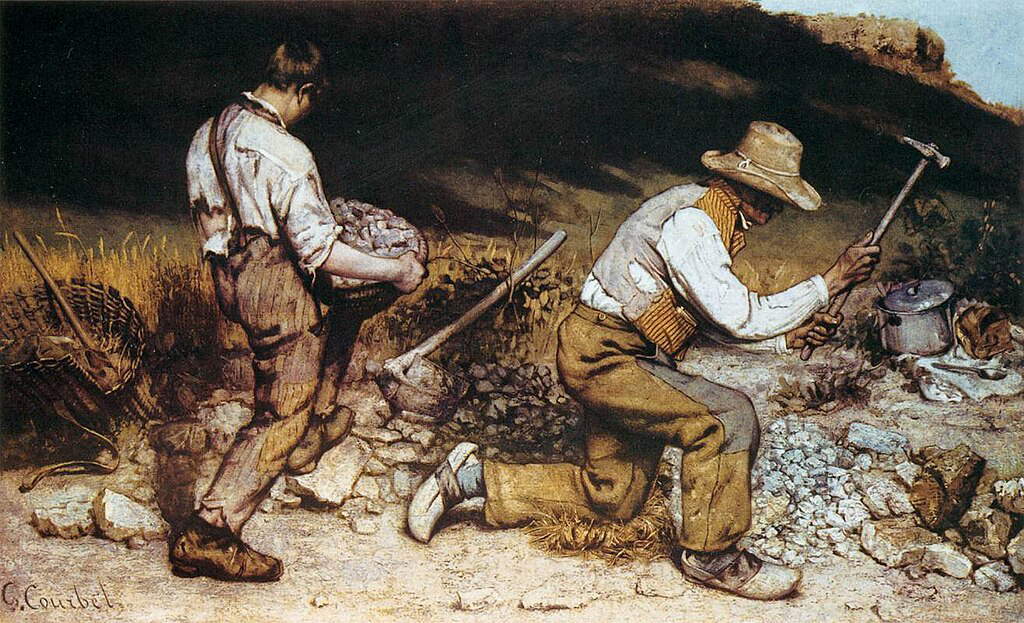

Beyond the few sales, Courbet was unable to fit into a social dimension that could recognize him as an established artist. He sent a few works to the Parisian Salons, continuing to be rejected because of the unconventionality of his work; it was not until 1844, with Self-Portrait with Black Dog that he managed to gain a first entry to the Salon, but he continued to be rejected thereafter. His best opportunity came when, with the fall of Louis Philippe and the proclamation of the Second French Republic, the jury was suppressed and his After Dinner at Ornans (1849) exhibited with praise, then purchased by the French state at the hands of Charles Blanc, director of the Beaux-Arts administration. In 1849, Courbet returned to Ornans and painted the three large canvases that really form the basis of the realist experience and configure him as its father. The Stone Breakers, Funeral at Ornans, and The Peasants of Flagey Returning from a Fair were exhibited at the Salons of 1850 and 1852. With these works Courbet proved that he had matured thoughts of participation in certain political ideas that pointed to a more democratic reformulation of values. These are productions that upset the art scene, especially because for the first time an artist chose large formats, everyday content, and no longer the prestigious genres or idealized characters.

In 1854 he began work on thePainter’s Atelier, in preparation for the 1855 Universal Exhibition. The painting was the manifesto of his poetics, but because of its large size it was rejected by the Salon. This rejection led Courbet to respond, in the same year, by setting up the “Pavilion of Realism,” as he decided to call the exhibition he built on Avenue Montaigne, a few steps away from the Exposition dedicated to the Fine Arts, to establish a direct confrontation, in open defiance of the Academy and pre-established traditions. Here Courbet exhibited all the most important works he executed after 1848, those more realist, inspired by events of contemporary life.

Between 1865 and 1869 Courbet spent summers in Normandy, between Le Havre and Étretat, where he cultivated his interest in landscape painting, seeking to immortalize the violent fury of the sea, an experience that resulted in the famous Waves series. With the defeat of the French army at Sedan at the hands of the Prussians and the fall of Napoleon III, the Third Republic was established in France. Courbet threw himself into the political arena: president of the Federation of Artists and in charge of the protection of works of art, he was then elected to the Council of the Commune, a socialist-anarchist government that led Paris from March 18 to May 28, 1871. After his speech in favor ofpulling down the Vendôme Column-celebrating Napoleon Bonaparte’s victory at Austerlitz (1805)-he was arrested and sentenced to six months in prison. As soon as he was released in March 1872, he was convicted again, which is why he chose the path of exile in La Tour-de-Peilz, on the shores of Lake Geneva, Switzerland. Although he was very comfortable in this country, he intended to return to his homeland as soon as the waters calmed down. But the painter-and more importantly the man-was caught in an unstoppable process of decay, due to his status as a political exile. He lost heart, giving himself to a scruffy lifestyle. He continued to paint, but his output suffered as a result of his suffering and frustration. He died at La Tour-de-Peilz, on December 31, 1877.

Gustave

Gustave

Courbet’s style and major works

Gustave Courbet’s earliest pictorial activity dates from the 1940s and consists of still timid executions aimed at respecting the models of the earlier Romantic masters, Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault. At these dates, the production is essentially portraiture: several times the painter drew and depicted his sister Juliette, portrayed his friend Baudelaire in the spontaneous act of writing. Courbet himself lent himself as a model: in his Self-Portrait with a Pipe he presents himself as an artist, his gaze lost in the void but retaining a certain sensuality and conviction. Still bohemian, the painter appears inSelf-Portrait with the Black Dog (1842), which he managed to exhibit in Paris in 1844.

Because of the informal poses of his subjects and theordinariness of his representations, Courbet’s works were punctually rejected by the jury of the Salons, at least until the late 1940s. Just after the outbreak of the revolutionary uprisings, in 1849 Courbet painted After Dinner at Ornans, a canvas that constitutes his first profession of realist faith. In the work, the painter depicted his father Régis, himself and two friends, in a situation that had nothing picturesque or anecdotal about it, but proposed thesimplicity of a petty bourgeois setting, isolated an instant of everyday life with a photographic gaze. It was the first work to be accepted and exhibited at a Salon: it provoked harsh criticism, primarily because of the character presented from behind, an already very anti-academic element. The work is dense with references to antiquity: the light coming from the right, in its cone-shaped luministic cut, reveals Caravaggio’s study in The Calling of St. Matthew. Rembrandt and Velazquez are also seen among the sources, as well as a debt to the Le Nain brothers.

At the turn of the 1950s, the revolutionary uprisings greatly shook Courbet, who from that moment formed a rather conscious political idea. So he took on a mission, a message that his paintings would somehow convey to a diverse audience. To speak to such a diverse audience, the painter drew on his own figurative sources from the great classical masters as well as from more widely recognized models. The result was a personal and extremely sincere painting in the full service of truth. It is here that realism can be said to have come to have a truly structured physiognomy, one that responded to the motto faut être de son temps, from which derived the need to adhere to and convey the objectivity of contemporaneity.

Courbet’s works were socially incendiary: the representations of lower class life were terribly immediate and concrete, far removed from the idealizations pursued by the Academy, devoid of the pleasant picturesque taste and oblivious of the “small format” cherished by the French of the Salons. Hence, if one can speak of realism, one can do so not so much of Courbet before ’48 but certainly in relation to the paintings the painter executed from 1849 to 1855. To 1849 date The Stone Breakers: the work offers a clear example of the artist’s conceptions. Little concern for compositional balance, unrigorous proportions, the distribution of masses shifts all to the right. The intention here is to denounce the inhuman toil of the two workers, two figures expressing clumsiness, stiffness, taciturnity. This oil on canvas was unfortunately destroyed in Dresden during World War II, but it was the starting point of the whole movement that spread across Europe, containing an implicit indictment of the most execrable effects of capitalism. Between 1849 and 1850 Courbet painted Funeral at Ornans: it scandalized critics first and foremost because of its large size (316per 668 cm). In this work the artist reread Rembrandt’s lesson on light. The work describes the first burial in the new cemetery in Ornans. The deceased is an ordinary peasant and those present at the burial are all portrayed life-size and from life. In this prevalence of brown tones, the viewer is fully called upon to participate, since he stands in front of the burial pit, right on the ledge. It is a democratic art, involving everyone and giving everyone the same dignity of reproduction, even the dog in the foreground. It was with the same popular and familiar spirit that Courbet painted The Peasants of Flagey returning from the fair, between 1850-1855. It was a painting of reportage and concreteness focused on thehic et nunc of the event.

The culmination of realist investigation would be accomplished in 1855, when Courbet executed ThePainter’s Atelier. At the center is his self-portrait intent on painting, the nude figure of the woman as an allegory of Painting. Groups of characters include Baudelaire, Champfleury, a child drawing, figures representing social categories and institutions (a poacher bears the likeness of Napoleon III). The mannequin, abandoned on the floor, personifies the rejection of academicism. Poised between realism and allegory, this painting repurposed at the Pavilion of Realism is the essence of Courbet’s art, in a snapshot of the world he experienced on a daily basis.

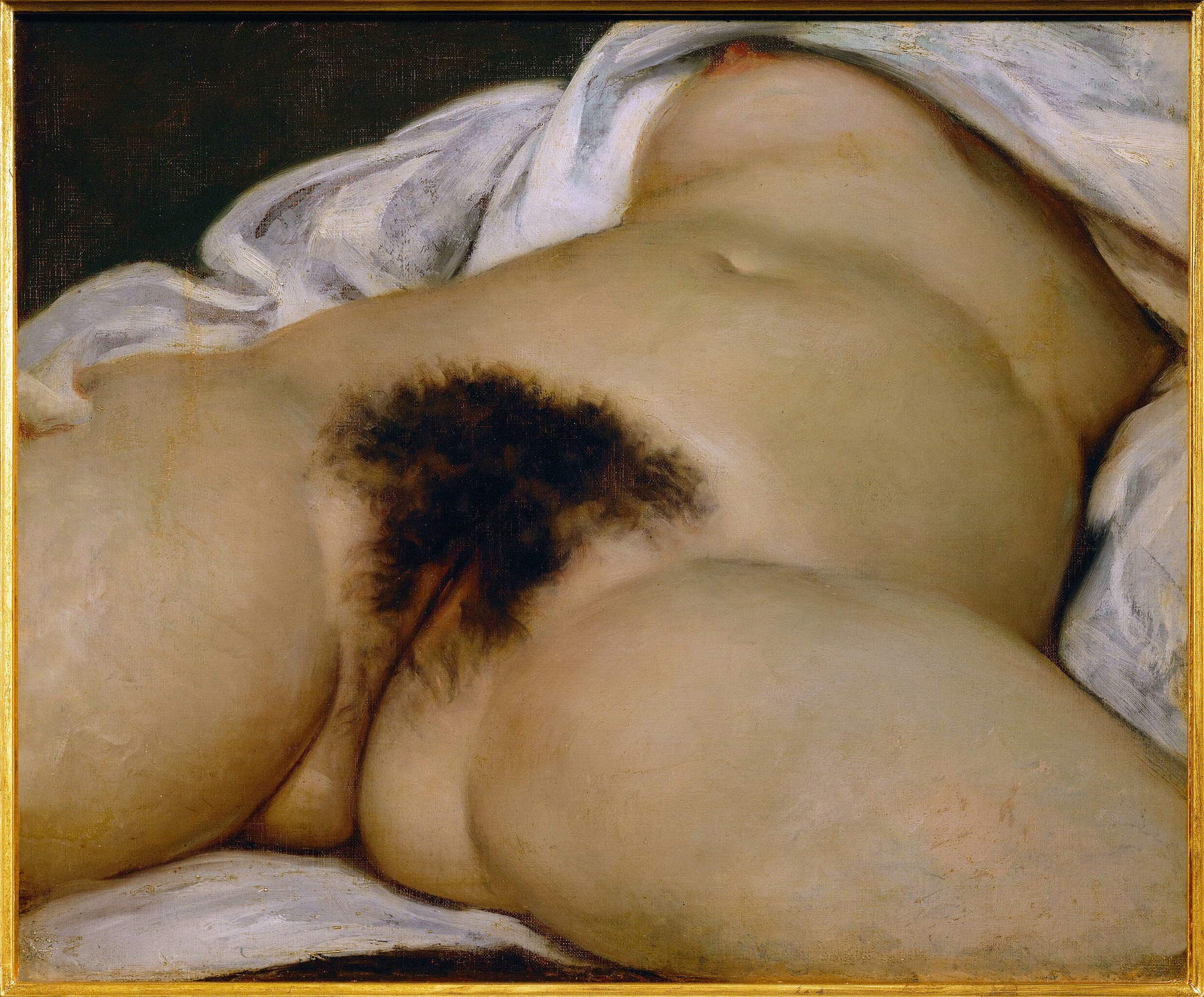

In later years, the painter took a path guided by his relationship with nature and eros: from Ladies by the Seine in 1856, to the more bluntly anatomical contemplation of female nature with theOrigin of the World, 1866. In this last work Courbet abandoned any kind of filter and let himself be carried away by all the audacity of which he was capable. The artist closed his career by devoting himself to landscape painting, almost a prelude to Impressionism. Part of a series, The Wave of 1870, preserved in Berlin, is a painting that pays homage to the immensity and imperious force of nature. In this work, Courbet explored the potential of matter, of color: it was executed with the use of the palette knife and through the force of the painterly gesture. Water, a liquid element, has the same gravity as rock: shapes and volumes make the blows of these waves more violent, fully restoring the concreteness of the marine scene.

Gustave

Gustave

Where to find Courbet works in Italy and abroad

In Italy, The Poachers of 1867 and La vague of 1871 are both kept at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome. Gustave Courbet’s most important works are in Paris, at the Musée d’Orsay: The Funeral at Ornans and ThePainter’s Atelier, but also TheOrigin of the World and The Trout from the very last period (1872). At the Petit Palais isSelf-Portrait with Dog (1842) and Maidens on the Bank of the Seine (1857).

Also in France are the above paintings: in Montpellier, the Musée Fabre presentsSelf-Portrait with Pipe, but also Bathers of 1853 andMeeting of 1854; in Lille is preserved After Dinner at Ornans, at Palais des Beaux-Arts; at the Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie in Besançon are Flagey’s Peasants Returning from the Fair. In Germany, the Stone Breakers were in Dresden before the 1945 bombing. Still in Berlin’s Nationalgalerie today, however, is The Wave of 1870. Overseas, however, The Young Women of the Village is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

|

| Gustave Courbet, life, works and style of the father of realism |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.