With the figure of Arcimboldi, Mannerism reached its most extreme consequences. The artist, a Milanese, had been trained in a particularly vital artistic environment such as mid-sixteenth-century Milan, which had seen the end of Sforza rule and the beginning of the Spanish period, which lasted until the eighteenth century: under Spanish rule the state of Milan did not experience any particular political upheaval for quite some time, but it went through a gradual decline that was felt especially around it. Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s training, however, began in a Milan that was still vital, a Milan where interest in Leonardo da Vinci ’s research was still alive and where the greatest artists of the Milanese Renaissance, from Bramantino to Bernardino Luini via Gaudenzio Ferrari, Marco d’Oggiono, the Bambaia, Cesare da Sesto and many others, had recently died out. This cultural temperament was progressively replaced by that of the artists of the Counter-Reformation, which was particularly alive in Milan, but before that there is the presence in Milan of Cremonese artists, above all Bernardino Campi, who was present in Milan from 1550, as well as other artists such as Antonio Campi and Giulio Campi who gravitated let us say in the orbit of Emilian Mannerism that drew on artists such as Parmigianino and Giulio Romano, and were still active between the 1530s and 1540s. It was outside Italy, however, that Arcimboldi experienced his greatest successes: in particular, at the court of Emperor Rudolf II in Prague he was master of ceremonies and was able to work steadily on his composite heads. Arcimboldi’s flair, after all, could not flourish in the Milan of the Counter-Reformation and Charles Borromeo, which had become more austere, less open to refined extravagance, and more inclined to an art steeped in severe religiosity.

Giuseppe Arcimboldi was born in Milan in 1527 to Biagio, a painter by profession, and Chiara Parisi. The family was noble, and the young Giuseppe was able to complete his education in a cultured environment. On the basis of documents, we know that in 1549 Giuseppe began working on the construction site of Milan Cathedral together with his father Biagio on some decorations but especially on the creation of two stained glass windows, one with stories from the Old Testament and one with stories of St. Catherine of Alexandria. The work would be finished by Giuseppe in 1556 (but he had been working on it alone since 1551). In 1556, the artist worked on the fresco with the Tree of Jesse in Monza Cathedral together with Giuseppe Meda. The work would be completed in 1559. The year before, in 1558, he was in Como where he worked on some models for the stained-glass windows of the cathedral.

In 1562 the artist was called to Vienna by the Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand I, who had evidently noticed him for some of his accomplishments in Milan (according to a recent hypothesis, for a very early series of his Seasons). As soon as he arrived, he made portraits of the ruling family. In 1563, the future emperor Maximilian II (who became emperor in 1564) commissioned him to paint the Seasons cycle, which was finished in 1566. Of the original cycle, onlySummer,Winter (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) and possibly Spring (Madrid, Museo de la Real Academia de San Fernando) are preserved.Autumn, on the other hand, is known only from later replicas. Joseph then officially became court portraitist in 1564, succeeding the elderly painter Jacob Seisenegger in that position. The artist made a brief sojourn in Italy in 1566 and in the same year painted the famous Librarian, a copy of which, very faithful to the original and chronologically close to it, is now preserved in Sweden in Skokloster Castle. In 1568 engono presented the two cycles of the Seasons and the Elements to Emperor Maximilian II (the presentation was by the scholar Giovanni Battista Fontana, or Fonteo).

In contrast, the drawing of theantelope cervicapra preserved in the Austrian National Library in Vienna, one of the artist’s most famous naturalistic studies, dates from 1570. In 1571, Giuseppe Arcimboldi was commissioned to organize the wedding festivities between Charles of Habsburg and Maria of Bavaria, while the series ofSeasons now in the Louvre dates from 1573. In 1576 Rudolph II became emperor following the death of Maximilian II and confirmed Joseph in his post. In 1582, on behalf of the emperor, Joseph traveled to Bavaria where he was assigned to evaluate the purchase of antiquities and works of art from the Fugger collections for the imperial collections. The collaboration between Giuseppe Arcimboldi and Ulisse Aldrovandi dates back to 1583, with the former sending the latter drawings for his nature studies. In contrast, the carnetcondrawings for costumes and party apparatuses now preserved in the Uffizi and dedicated to Rudolph II dates from 1585. Around 1590, the painter made theOrtolanus, his most famous reversible head, and also around the same year, Giuseppe Arcimboldi painted the portrait of Rudolph II as the god Vertumno (made as one of his composite heads). In 1592 the artist was appointed count palatine by Rudolph II. Giuseppe Arcimboldi returned to Milan and died in his hometown on July 11.

The son of a painter, Biagio Arcimboldi, who was a friend of Bernardino Luini, the very young Giuseppe was thus immediately in contact with Leonardoesque circles (the art of Leonardo da Vinci would be fundamental for him as it inspired many of his mature studies), and it was in his father’s workshop that he began to work. His first documented work are two stained-glass windows for Milan Cathedral (they are dated 1549: Arcimboldi, however, did not make the cartoons from which these windows would be taken by himself but rather in collaboration with his father Biagio, and the cartoons would later be translated into glass by a German glassmaker, Corrado Mochis, who had long been active in the Milan cathedral building site). These are works from which it can be seen that Giuseppe Arcimboldi was up-to-date with respect to the novelties of Mannerism, whose great vivacity the artist takes up, however, grafting it onto a monumental base. Arcimboldi’s early Mannerism can be found again in another of his youthful achievements, a fresco in Monza cathedral painted in collaboration with Giuseppe Meda between about 1556 and 1559(The Tree of Jesse: a monumental and imposing fresco, with charged figures and a cool, muted color palette). Called to Vienna in 1562 by Ferdinand I of Habsburg, Arcimboldi was immediately engaged as a portrait painter, so much so that he was appointed court portraitist in 1564 by Maximilian II, who had a great fondness for Giuseppe Arcimboldi. Several of his are preserved in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna: for example, the portrait of Archduke Maximilian (future Emperor Maximilian II) together with his wife Mary of Spain and three children, a work of 1563 with “institutional,” detached and austere tones.

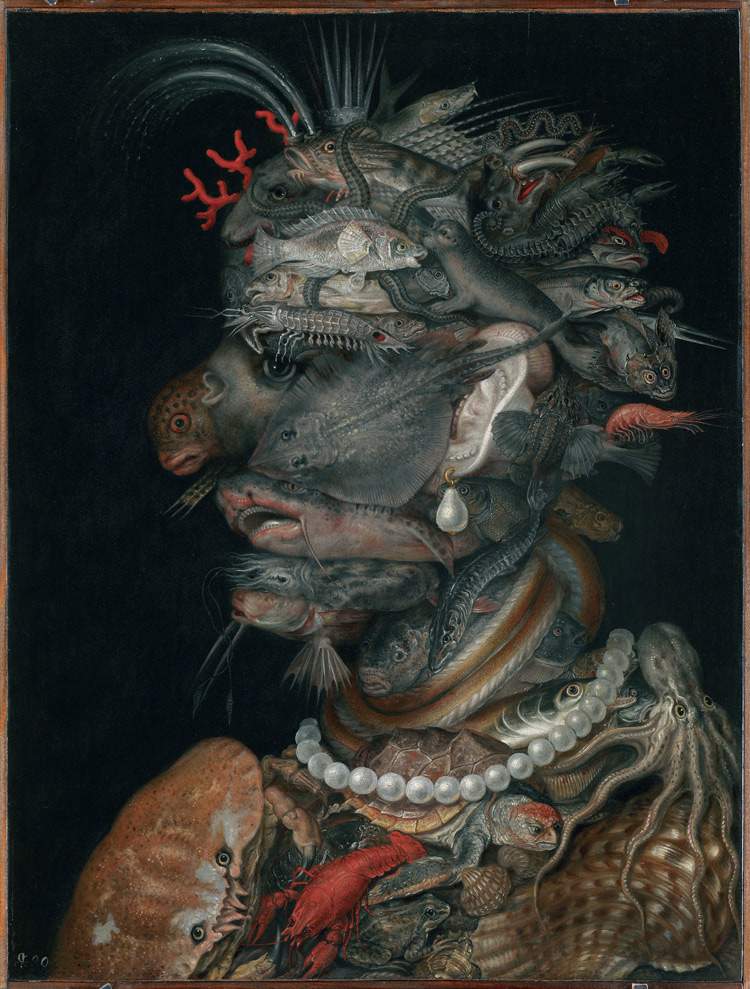

Official portraiture, however, was a genre that was close to Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s heart, and from 1563 he first began working on his composite heads, which ensured his success and fame as an imaginative and ingenious artist. The first cycle of composite heads is that of the Four Seasons, made between 1563 and 1566 for Maximilian II: of the originals only theSummer andWinter remain, preserved in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and a Spring in the Museo della Real Academia de San Fernando in Madrid that may be the third original but there is no certainty about it (theAutumn, on the other hand, is considered lost and is known only from later replicas, for example that of the 1573 cycle preserved in the Louvre, which is almost identical to the original). Composite heads are so defined because they are composed of several elements, all pertaining to a theme, forming a portrait: spring’s head, for example, is composed of flowers and leaves (botanical scholars have counted about eighty different species of plants and flowers, a sign of Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s high interest in the world of nature), summer has a head made up of typical summer fruits (the cheek is a peach, the chin a pear, the nose is a cucumber while the hair is made up of plums, cherries, raspberries, and a bunch of grapes that are still unripe, the ear is a corn cob, and the torso is made up of ears of corn all intertwined). On the occasion of the exhibition on the painter held in Milan in 2011, some scholars questioned whether the Viennese cycle was the first on the theme made by Giuseppe Arcimboldi, even advancing the hypothesis that the imperial court noticed the young Milanese artist by virtue of the fact that he may have already begun to make paintings of this type in Milan, which would thus have stimulated the interest and curiosity of Ferdinand I of Habsburg, who decided to call him to Vienna.

What is the significance of these paintings? Perhaps they would be nothing more than a celebration of the Habsburg court: so thought the scholar Giovanni Battista Fontana, who was active at the Habsburg court in the 1660s. In one of his writings, Fontana suggests seeing elements and seasons as allegories of the empire: in particular, the paintings would be to be read from an Aristotelian perspective (according to Aristotle, the universe was assimilated to a macrocosm composed of the four elements, and this was a conception that rested its foundations on even more ancient philosophies, and again according to this way of viewing reality, each element corresponded to a different season, symbolizing the passage of time of the univers). And since the heads are likened to portraits of caesars, Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s composition would be understood as the empire reigning and ruling over both the macrocosm and the microcosm, since the emperor takes on the likenesses of components of both the macrocosm and the microcosm (another famous cycle is that of the Four Elements, air, water, earth and fire, which some scholars believe is related to that of the Four Seasons).

Other interesting works by Giuseppe Arcimboldi include the 1566 Librarian (which probably depicts a personage from the court of Maximilian II who was actually a librarian: it thus denotes the artist’s interest in Leonardo’s caricatures, which was common to the entire Milanese artistic milieu of the first half of the 16th century), and reversible heads, that is, paintings that look like still lifes on one side, but by turning them upside down become composite heads: and the most famous example is the very famous Hortolanus of about 1590, preserved in the Museo Civico Ala Ponzone in Cremona. It looks like a still life, a bowl filled with vegetables, with onions, potatoes, mushrooms, and whatnot, but by turning the painting upside down, a caricatured depiction of an ortolan appears (the nose is the potato, the onion is the cheek, the mushrooms shape the lips, and the bowl becomes the character’s hat). Finally, as anticipated, Giuseppe Arcimboldi had strong interests in the natural world. A contemporary and indeed almost the same age as Ulisse Aldrovandi, the great Bolognese scientist, he was greatly inspired by the latter’s studies, and vice versa Aldrovandi greatly enjoyed the works and drawings of the Milanese painter, so much so that on a few occasions the two collaborated, with Arcimboldi providing Aldrovandi with illustrations for his studies. A correspondence between Aldrovandi and Francesco de Paduanis, a scholar active at the court of Prague, is preserved, in which De Paduanis let the Bolognese scholar know that he had obtained from Arcimboldi some representations of animals for Aldrovandi’s studies and would send them to him. One of the most famous illustrations is the cervicapra antelope preserved at the University of Bologna Library, which was used for Ulisse Aldrovandi’s studies. There is also a codex preserved at the Austrian National Library in Vienna, known as the Bestiary of Rudolph II, in which numerous natural representations by Arcimboldi are preserved (mainly of animals: deer, pheasants, lizards, wild boars, cranes, and iin general animals that Arcimboldi probably saw in imperial gardens and hunting grounds). Thus Giuseppe Arcimboldi was not only a great artist, but he was also very well inserted in the scientific circles of the time.

An artist who made a career among the courts of Europe and therefore can be found in many museums, Giuseppe Arcimboldi is little represented in Italy: his most famous works, the “composite heads,” were in fact made for the courts of Vienna and Prague and are therefore found abroad. In Italy, the itinerary to discover Arcimboldo starts at Milan Cathedral, where his two stained-glass windows can be admired. Also in Lombardy is Arcimboldi’s most famous work in Italy, namely theOrtolano in the Ala Ponzone Museum in Cremona. TheTree of Jesse, a fresco in the Duomo, is seen in Monza, and several of his drawings can be found in the Prints Cabinets of the Uffizi in Florence and the Strada Nuova Museums in Genoa, as well as in the University Library in Bologna, but they are rarely exhibited because of their delicacy.

The most famous cycles of composite heads are found abroad, at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, at the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen in Munich (the one in Munich is complete, although theAutumn, in precarious condition, is kept in storage), and at the Denver Art Museum. In Sweden, Skokloster Castle preserves a faithful copy of the Librarian (the autograph is not known to us). Other works are at the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, in the collections of the Princes of Liechtenstein in Vienna, at the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, and at the Museo de la Real Academia de San Fernando in Madrid.

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, life, style and works of the bizarre Mannerist artist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.