Giorgio De Chirico: metaphysical painting, life, works

Intent on renewing Italian art by opening it to the experiences that were forming in early 20th century Europe, a great many Italian artists at the turn of the century chose to leave Italy for some time to seek new insights elsewhere. Among these “cosmopolitan” artists can also be counted Giorgio de Chirico (Volos, 1888 - Rome, 1978), who stayed in Paris between 1911 and 1915 just as the French capital was also the... European art capital. De Chirico was also strong in open Mediterranean culture, which he had also acquired through his birth (the artist was in fact born and lived for a long time in Greece), and by staying in Munich he had moreover come into contact with German art. From these experiences, De Chirico matured the need to develop a new language, which in fact proved to be among the most original and also among the most enigmatic of the twentieth century. De Chirico is considered the father of metaphysical painting, which was born as a reaction to the Cubist and Futurist avant-gardes and posed as one of the most innovative experiences of the first part of the century.

De Chirico today is best known for the works he created in the first part of his career: he was indeed a very long-lived artist (he lived to be ninety), but it is mainly the works of the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s that have entered the collective imagination. Works that appear as if suspended, traversed by visions on which mysterious symbols and elusive characters move, dreamlike images and complex allegories that can be read only if one keeps in mind the composite and heterogeneous culture that nourished the imagination of Giorgio de Chirico, who was moreover always close to the literary circles of his time (two great literary figures such as Guillaume Apollinaire and Jean Cocteau held De Chirico in high esteem).

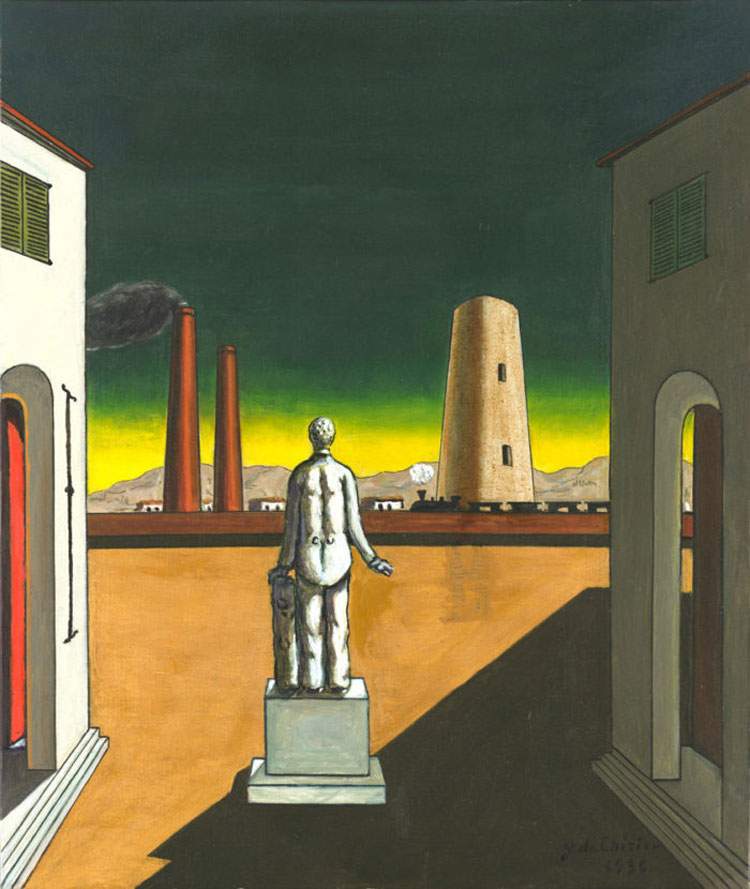

Nicknamed Pictor optimus because of his crystalline technique (the Latin, on the other hand, is a tribute to his profound classical culture, which the artist had also acquired by virtue of his training in Greece), Giorgio de Chirico was an artist who spanned the entire twentieth century, experiencing different phases: a debut under the banner of German culture with Böcklinesque works, the first metaphysical season of the 1910s, the 1920s with the works of the “classical” period, then again the second metaphysical season between the 1920s and the 1930s coinciding with his second stay in Paris, to arrive at the themes of tradition tackled until the 1950s and ending his career with a return to metaphysics (so much so as to speak of “neo-metaphysics”). “De Chirico,” reads the introduction to the exhibition that Palazzo Blu in Pisa has dedicated to him from Nov. 7, 2020 to May 9, 2021, “imagines views of ancient cities that are superimposed on visions of modern cities taken from places of lived life, first Volos and Athens, then Munich, Milan, Florence, Turin, Paris, Ferrara, New York, Venice, Rome. These are places in which public space uninhabited by man is populated by objects (fragments, ruins, arches, arcades, street corners, walls, buildings, towers, chimneys, trains, statues, mannequins) that estranged from their usual context emerge with all their iconic force, becoming unreal, mysterious, enigmatic.”

|

| Giorgio de Chirico, Struggle of Centaurs (c. 1909; oil on canvas, 75 x 110 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Giorgio de Chirico, Metaphysical Composition (1950 - 1960; oil on canvas, 60 x 50 cm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi - Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Giorgio de Chirico, Present and Past (1936; Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

Giorgio de Chirico: life

Giorgio de Chirico was born in Greece, in Volos (in the region of Thessaly), on July 10, 1888, to Italian parents of noble birth: his father, Evaristo, was an engineer by trade and was in Greece on business. For some years the family resided in Greece: Giorgio himself studied for several years in Athens before moving, in 1906, to Italy with his brother Alberto Savinio (Andrea Francesco Alberto de Chirico; Athens, 1891 - Rome, 1952), then moving to Germany in 1907, where he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, learning about the art of Arnold Böcklin and Max Klinger. Again, he moved in 1909 to Milan and then moved in 1910 to Florence, and again from 1911 to 1915 to Paris.

However, the city to which De Chirico was probably most attached was Ferrara: the artist moved to the Emilian city after the beginning of World War I. Ferrara was in fact home to the XXVII Infantry Regiment to which the De Chirico brothers, who had enlisted as volunteers, were assigned. In the city, De Chirico met Carlo Carrà , Filippo De Pisis and Giorgio Rea. The artist remained in Ferrara until the end of 1918 and from January 1, 1919, moved to Rome, where he stayed until 1925: it was in Rome, at the Casa d’Arte Bragaglia, that his first exhibition was held. Between 1925 and 1935 the artist lived between Paris, Milan and Florence, and later he also attempted the American experience: in fact, Giorgio De Chirico left for New York in 1936, where he stayed for two years. He then stayed for a few months in Milan, and then went to Paris, where he moved as he was disgusted with Fascism’s racial laws. Returning to Italy in 1944, he settled permanently in Rome, where he married Isabella Pakszwer in 1946 and where he remained for the rest of his life, finding accommodation at number 31 Piazza di Spagna, the house where he lived until his death. His last years were those of neo-metaphysical painting: between the 1960s and the 1970s, in fact, De Chirico retraced the themes he had addressed in the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s. A major anthological exhibition was held in Milan in 1970, and the publication of the Giorgio de Chirico general catalog dates from 1971. The artist died in Rome on November 20, 1978.

|

| Giorgio de Chirico, Tired Troubadour Orpheus (1970; oil on canvas, 149 x 147 cm; Rome, Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico) |

Metaphysical painting: de Chirico’s research

“The metaphysical work of art,” wrote Giorgio de Chirico in Sull’arte metafisica of 1919, “is as far as the appearance is serene; it gives the impression, however, that something new must happen in that same serenity and that other signs, in addition to those already apparent, must take over on the square of the canvas. Such is the revealing symptom of inhabited depth.” The idea of the Italian-Greek painter was to give birth to an art that would overcome the excesses of the avant-garde, that would return to look at tradition (both in terms of techniques and content), but without proposing an art incapable of severing ties with the past: for this reason, too, De Chirico departed from the naturalist research that other of his contemporaries (such as Gino Severini, for example) had begun to pursue after the end of World War I, in the period of rappel à l’ordre, the return to order after the avant-garde “hangover” of the first fifteen to eighteen years of the century. De Chirico thus devised a revelatory art, one that blended dream and reality, irony and classical tradition, the mysterious and the rational, an art that could make us see things as if we were seeing them for the first time.

Why is it called metaphysical painting? Because according to De Chirico the task of art is not to reproduce reality, but it is to go beyond (“metaphysics” therefore in the etymological sense of the term: “beyond physics”), to explore, if anything, the complexity of reality, what lies at its base, the relationships that give rise to reality. Without, however, having the pretension of arriving at knowledge: it is not possible to arrive at the essence of things, everything appears to us as the manifestation of something that is elusive (these are ideas from which we infer his classical culture and in particular the influence that Plato’s writings had on him). This, then, is why his paintings are composed of objects that can often appear so distant from each other: because unexpected or surprising relationships go beyond reality.

A cerebral and visionary art, which also had several detractors, who did not appreciate De Chirico’s intellectualisms, considered excessive. The artist defined his research this way, with his proverbial candor: “The word metaphysics, with which I christened my painting [...] aroused not inconsiderable misunderstandings. The word would make one think that those things that lie after physical things must constitute a kind of nirvanic void. Pure imbecility. What I have attempted in art no one attempted before me: the spectral evocation of those objects that universal imbecility relegates to uselessness.” Seemingly superfluous but profoundly revealing details, suspended atmospheres, as if we were waiting for an event to occur at any moment, almost improbable juxtapositions, classical motifs, uninhabited city squares traced with geometric rigor: these are the elements that bring Giorgio de Chirico’s art to life.

|

| Giorgio de Chirico, Ariadne (1913; oil and graphite on canvas, 135.3 x 180.3 cm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

|

| Giorgio de Chirico, Enigma of a Day (1914; oil on canvas; São Paulo, Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo) |

|

| Giorgio de Chirico, Hector and Andromache (1924; oil on canvas, 98 x 75.5 cm; Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

Giorgio de Chirico’s major works

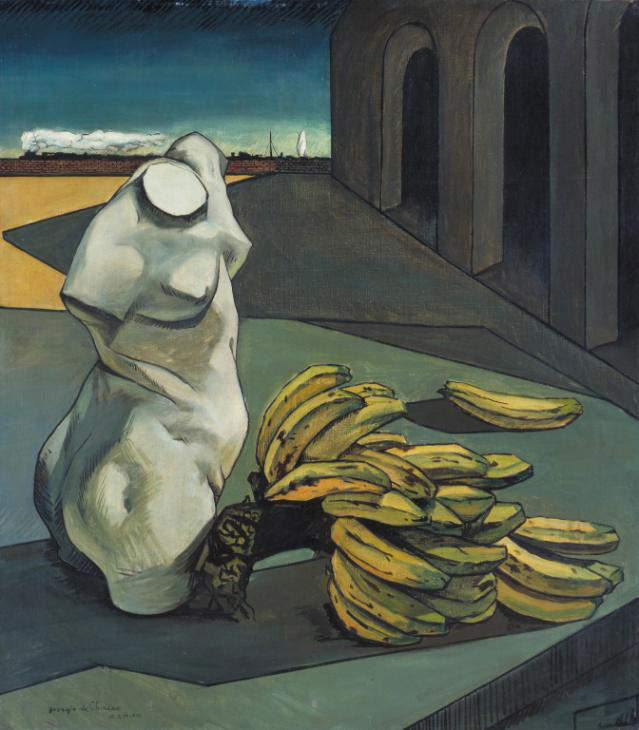

Among the artist’s earliest works it is possible to mention a masterpiece preserved at the Tate Gallery in London, entitled The Uncertainty of the Poet and dating from 1913: we find a female bust, that of a classical Venus, a helmet of bananas, an archway serving as a backdrop and a train passing by blowing in the distance. Both the past (represented by the Venus) and modernity (represented by the train) coexist here, as well as a sense of precariousness, of ephemerality (represented by the bananas that, in their ripening process, have already begun to blacken). De Chirico also challenges the rules of our perception by distorting the painting’s perspective and creating unrealistic shadows. There are especially two aspects that emerge from this painting: the first concerns communicating to the relative the inexplicability of reality. This is why De Chirico’s works are shrouded in a sense of mystery: because it is not possible to arrive at a perfect knowledge of the world. The second concerns the ability of the artist, a kind of demiurge who is able to construct a world that does not exist.

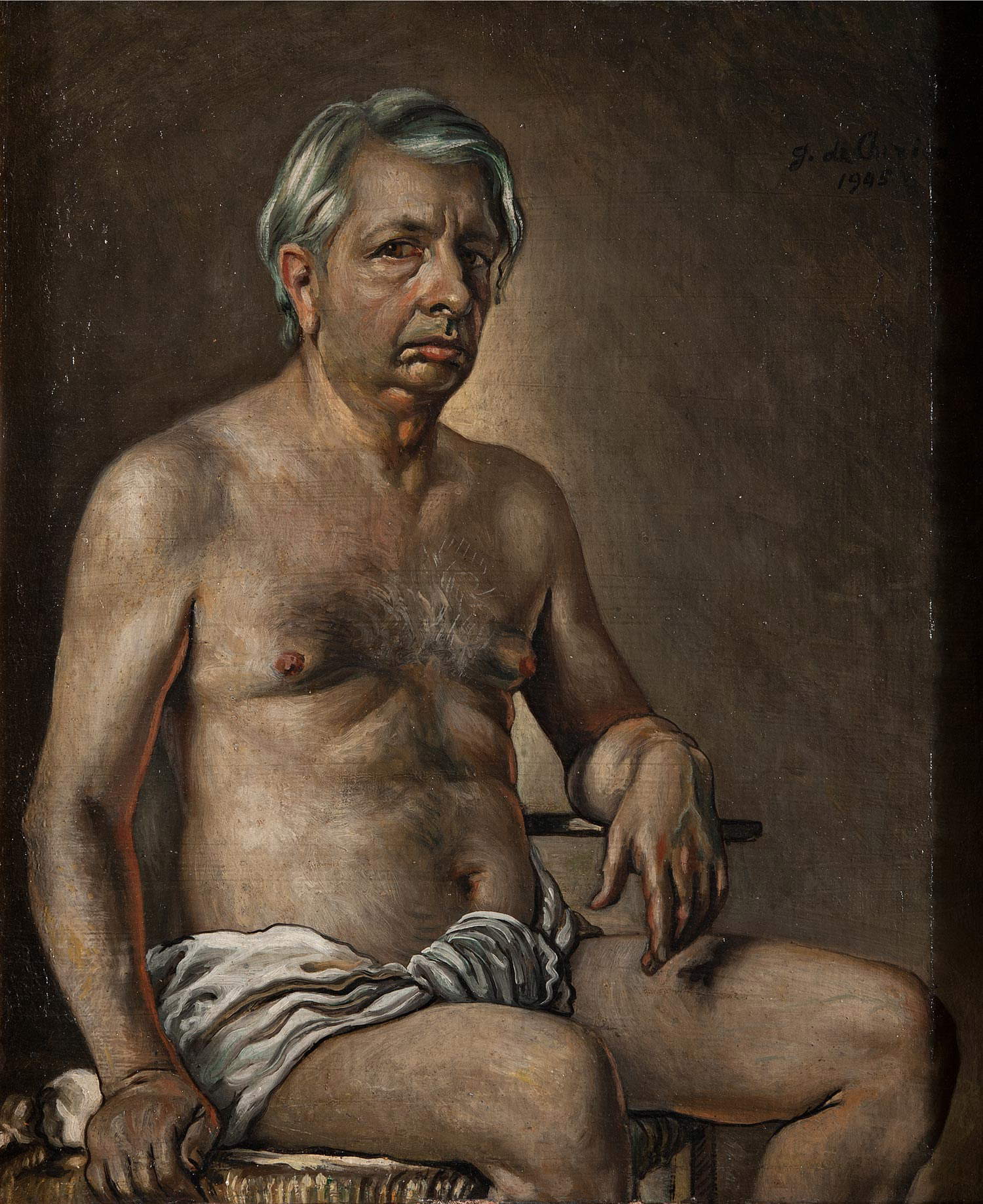

It is for this reason that De Chirico’s art is teeming with self-portraits, which the artist executed in great quantities. The artist made more than a hundred: “Insisting on one’s own face,” wrote art historian Maurizio Fagiolo Dell’Arc, “is a fact that sinks into De Chirico’s own culture: and I do not tire of repeating that it is only that of Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Weininger (and scholars who look for other routes are a bit of a pain). So the pictor optimus as superman.”

Perhaps the best-known masterpiece of the Volos-born painter is The Disquieting Muses, which the artist produced in several versions and variations. There we find De Chirico’s famous mannequins, one of the constant presences in his art, a symbol of the human condition (the mannequins cannot see, hear or speak). We find Ferrara’s Castello Estense closing the background, next to the smokestacks of a modern factory: again, the glorious past and the industrial present coexist in De Chirico’s painting. The square itself, however, does not appear as it is in reality: it becomes a kind of grand stage, as if life were a kind of play that goes on for eternity crossing all epochs. Parody, irony, even fierce irony (of which the artist, by the way, also gave proof in the writings he left us), mystery, ambiguity, subversion of all logic, a sense of abstraction: these are the ingredients that de Chirico employs to make the viewer realize how elusive, mysterious, and distant reality is.

|

| Giorgio de Chirico, The Uncertainty of the Poet (1913; oil on canvas, 106 x 94 cm; London, Tate Gallery) |

|

| Giorgio de Chirico, Self-Portrait (1940-45; oil on canvas, 28 x 33 cm; Turin, GAM - Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Giorgio de Chirico, Nude Self-Portrait (1945; oil on canvas, 60.5 x 50 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

![Giorgio de Chirico

Le muse inquietanti (1925 [1947]; olio su tela, 97 x 67 cm; Roma, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) Giorgio de Chirico

Le muse inquietanti (1925 [1947]; olio su tela, 97 x 67 cm; Roma, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2021/fn/giorgio-de-chirico-muse-inquietanti-roma.jpg) |

| Giorgio de Chirico, The Disquieting Muses (1925 [1947]; oil on canvas, 97 x 67 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

Where to see Giorgio de Chirico’s works in Italy

De Chirico was a very prolific artist, and as a result there are several museums in Italy that house his paintings and in some cases even his sculptures: almost all museums that have a collection of twentieth-century art also include works by the “pictor optimus.” If one wants to learn about his art in depth, however, there are some must-sees. You can start at the very address where the painter lived and worked: in fact, at number 31 on Piazza di Spagna today is the Casa Museo, which can be visited by appointment (visits are managed by the Giorgio and Isa de Chirico Foundation). The Foundation’s collection includes several hundred works by the artist. Second to the Foundation in terms of the number of works by the painter is probably only the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome, a possible “second stop” on a Roman tour to discover Giorgio De Chirico.

Other museums where it is possible to see works by De Chirico are GAM in Turin, Galleria Ricci Oddi in Piacenza, the Roberto Casamonti Collection in Florence, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna at Palazzo Pitti in Florence, the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, and the Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna in Venice. A good core of works from the late phase of the painter’s career is preserved at the MART in Rovereto, while if you want to see works by De Chirico in the city that perhaps most associates with his name, you will need to visit the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea “Filippo De Pisis” in Ferrara.

|

| Giorgio De Chirico: metaphysical painting, life, works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.