Gino De Dominicis, the artist against convention. Life, major works, themes

Gino De Dominicis (Ancona, 1947 - Rome, 1998) was one of the most discussed Italian artists of the 20th century: He expressed his art through different techniques, namely painting, sculpture and architecture, freeing himself as much as possible from all conventions related to the art world, starting from the need to limit photographic reproductions of his works to a minimum to the rejection of certain terminologies such as “performance” or “conceptual art.”

For De Dominicis, the main focus had to be on ’art itself, the only possible way for him to investigate a series of themes on which he has focused all his life, namelyimmortality, being able to achieve the impossible,immobility, and ancient cults, particularly the Sumerian civilization. He often declined his reasoning in a surreal or ironic key, for example by inserting long unnatural noses on the faces of the protagonists and even on skeletons, another recurring element of his artistic production.

The life of Gino de Dominicis

Gino De Dominicis was born on April 10, 1947, in Ancona, the capital of the Marche region, and studied at the city’s Art Institute. Among his teachers was the artist Ettore Guerriero. As early as 17, De Domincis exhibited his first works in a local gallery. He moved to Rome in 1968, after making several trips, and came into contact with the Via Brunetti group, Laboratorio 70, formed by artists Gianfranco Notargiacomo, Paolo Matteucci and Marcello Grottesi, being impressed by their innovations. De Dominicis tried several times to join the group by talking directly with Grottesi, and was actually admitted shortly thereafter.

The Via Brunetti group was characterized by a series of performative acts carried out in the streets and squares of Rome, disrupting its everyday life, sending a message of opposition and rejection toward places appointed to art such as museums and galleries. Some examples of their works were the Pincus Pills in St. Peter’s Square and the Guillotine in Piazza del Popolo. De Dominicis’ first solo exhibition took place in 1969 at Fabio Sargentini’s L’Attico gallery, which emphasized his innovative contribution even in comparison with the gallery’s two other leading artists, Pino Pascali and Jannis Kounellis.

He participated numerous times in the most important international exhibitions: he was often present at the Venice Biennale, starting in 1972 until the 1990s; he was also invited to Documenta in Kassel; finally, his experience at the Paris Biennale was significant, where he exhibited in 1973, won the International Prize in 1982 and participated again in 1985.

Between 1985 and 1986 De Dominicis participated in Washington in a group exhibition entitled A New Romanticism, Sixteen Artists from Italy. In 1986 he collaborated for the first time with gallery owner Lia Rumma in Naples, with whom he worked on several other occasions, and finally, Adelina von Fürstenberg organized a major retrospective exhibition in his honor at the Centre National d’Art Contemporain le Magasin in Grenoble in 1990.

De Domincis died in Rome on November 29, 1998, and after his death several exhibitions and reviews were organized to remember him. The first took place in New York’s P. S. 1 Contemporary art center a year later, in 1999, under the title The game room; then in the city of Rome a major retrospective was held in the National Gallery of Modern Art and then another in 2010 inside MAXXI, entitled Gino De Dominicis. The Immortal.

The style and works of Gino De Dominicis

De Dominicis was a charismatic and eccentric artist who expressed his ideas and beliefs through various forms of art. He believed that art was a moment of magic, and not a means of communication, eschewing any convention that is usually created around it. For example, he clearly spoke out against the use of certain terminologies, or he felt that the presence of the audience was unnecessary, without which art could and should exist anyway; moreover, he was highly renowned for refusing to have his works photographed.

His art focused on recurring themes concerning death and immortality; the ability to succeed in the impossible and to stop the irreversibility of time, identifying the role of art in this regard; the need to refute the irreversibility of scientific phenomena. He had also made these issues explicit in a paper dated 1966, Letter on the Immortality of the Body. In addition, De Dominicis often used archetypal alchemical and religious symbols, such as crosses, pyramids, stars, geometric figures, and endowed the profiles of his figures with long, unnatural noses. The element of the nose has special significance, as it connects the most “spiritual” part of the face, that of the mind, to the lowest, where the mouth resides.

One can divide De Dominicis’s work into two distinct periods. The first is between the late 1960s and the late 1970s and was referred to as “conceptual,” a definition that later proved to be very hasty and approximate, belied both by the artist himself and by critics. The second period runs from the early 1980s until his death in 1990, and is characterized by an innovative revival of figurative painting.

De Dominicis’s early works often feature an auction. For example, in Untitled (1967- 1969), a long golden rod is placed touching the edge of a boulder with one pointed end. The point of contact between the rod and the stone is a millimeter area, so small that it almost does not justify the arrangement of the elements in balance. This creates an incongruity that occurs in nonexistent and simultaneously infinite time. In Equilibrio (1969), the golden rod is represented in suspension of space, almost as if it were the line that gives rise to the entire action. Around the rod, invisible objects are placed, such as The Cube, the Cylinder, the Pyramid, so defined because the artist only draws their outlines on the floor.

His research shortly thereafter flows into performative acts, aimed at investigating the more elusive, intangible and invisible aspects of art. However, De Dominicis did not use the term “performance,” as he considered it more akin to the world of theater than art. Indeed, unlike other performances by artists contemporary to him, De Dominicis rarely places figures in motion, with the exception of two films dated to 1969, Attempt to make squares instead of circles form around a stone falling into water and Attempt to Fly. In the first film, De Dominicis returns to the concept of the dialogue between the square and the circular form; moreover, he reflects on movement as an invisible presence in the form of waiting or expectation of the stone falling into the body of water. Also dated 1969 is the sculpture The Time, the Mistake, the Space composed of a human skeleton lying on the ground wearing roller skates, while on one finger he holds a pole in balance and simultaneously carries a dog skeleton on a leash. In this work, “space” is constituted by verticality, while “wrongness” by the desire to move horizontally and even more so by the desire for the acceleration suggested by the skates.

They date back to 1970 Zodiac, in which he realistically represented the twelve signs of the zodiac by presenting a bull, a live lion, a young girl who is really a virgin and two dead fish, arranged in a semicircle; and Mozzarella in a Carriage, literally a real carriage inside of which is placed a mozzarella. This very work helped to undo De Dominicis’s idea of himself as a conceptual artist, as it was conceived so that the words of the title were visualized concretely, materialized. In addition, the work was intended to be a critique of the notion that the “container of art,” i.e., the gallery or museum, can turn any common object into a work of art, while the mozzarella remained as such even when placed in a luxurious container. Even in an exhibition in Enzo Sperone’s gallery in 1982, the same concept would be reiterated by placing a toilet among other works of art and emphasizing that it remained a toilet, with no other meaning. De Dominicis himself will call these “homeopathic operations,” in the sense of ways the artist identifies to criticize the trends and methodologies in vogue at the time.

Among the works dated to the early 1970s, it turned out to be rather controversial Second Solution of Immortality (L’Universo è Immobile) the 1972 work that De Dominicis presented at the Venice Biennale. A young man with Down’s syndrome was made to sit in a corner in front of an invisible cube, a rubber ball portrayed in the moment before rebounding after a two-meter fall, and a stone waiting for a causal movement capable of moving it. The elements were placed in a room in which De Dominicis asked that all the covers to the skylights be removed in order to establish contact between the room and the universe. Assistant Simone Carella said about this work that “Gino considered the room a summa, but not arithmetic, of the things he had done until then.” It was the choice to involve the boy that elicited several critical reactions from both critics and the public. De Dominicis’ intent was not to portray a young man with a particular difficulty, but to portray the “solution of immortality” of the title through a man who had retained the air of a child, thus deceiving time.

Other notable “acts” of the 1970s were a cocktail party organized in Rome to celebrate the overcoming of the second principle of thermodynamics in 1972, and an exhibition organized in the Lucrezia De Domizio Durini gallery in Pescara whose entrance was reserved exclusively for animals, as beings that have no awareness of death, adding another element to his digressions on immortality.

At the turn of the late 1970s and 1980s De Dominicis entered the so-called second period, making drawings and figurative paintings with basic techniques, such as tempera and pencil on panel or paper. He also used canvas, but more rarely. The themes he tackled in this phase are similar to those investigated in the previous years, analyzing them in a renewed way. De Dominicis deepened his knowledge of ancient cultures during this period, particularly the Sumerian civilization, which exerted a particular fascination in him as he became convinced that they had “invented everything” since they predated the Egyptians and Greeks. In particular, he represented very frequently and in various forms the Sumerian myth of Gilgamesh, which is closely related to immortality. Gilgamesh, in fact, was the king of Uruk, a mythological city believed to be in present-day Iraq, and decided to make a long and dangerous journey to find the secret of eternal life. De Dominicis often pairs the figure of Gilgamesh together with that of Urvasi, an immortal female goddess found in Indian tradition who is loved by a mortal man. By presenting them together in the same work, he intended to unite the masculine (Gilgamesh) and the feminine (Urvasi), showing their profiles facing each other, and at the same time wished to create a kind of short circuit between cultures of two different peoples. It is no coincidence that in Untitled (1988) between the two profiles drawn in white color the landscape of Mesopotamia appears.

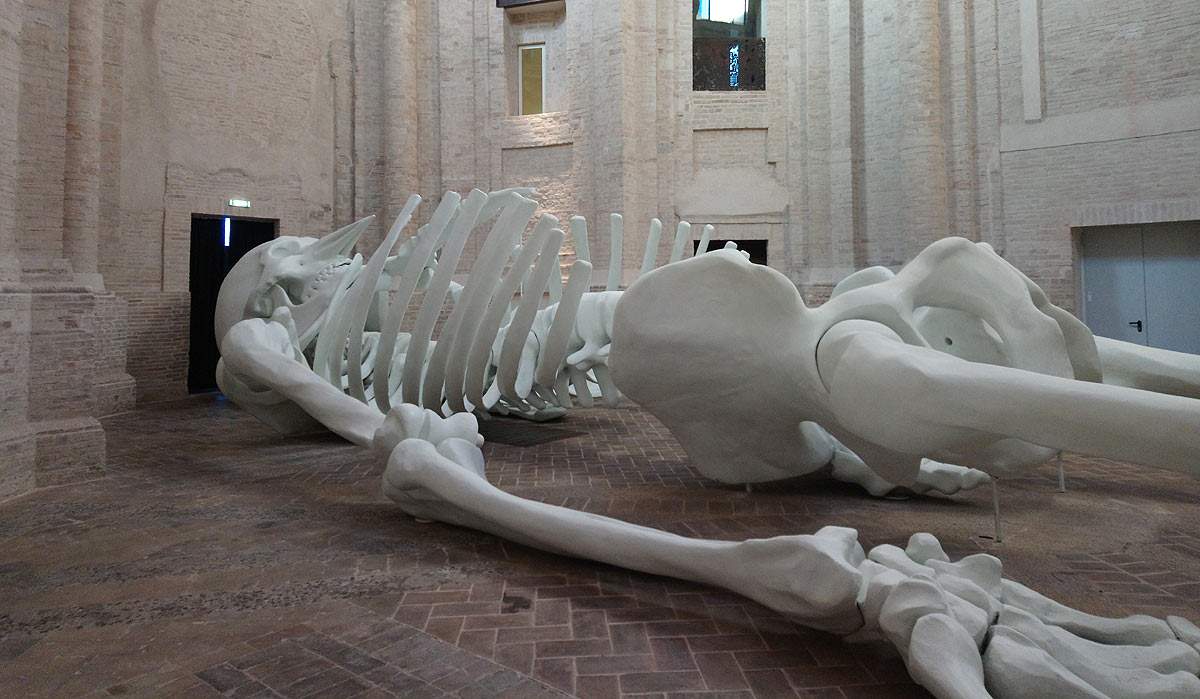

In the same period long and pointed noses appear again, which are also applied in an ironic and surreal way on skeletons, as happens in Cosmic Magnet (1988). This work, first shown in the anthological exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Grenoble, and now preserved in the deconsecrated church of Santissima Trinità in Annunziata in Foligno (Perugia), has become the artist’s most famous work.

Shortly thereafter, De Dominicis presented at the Monti Gallery in Milan Lampadario antientropico, hanging from the ceiling a plastic bag in which he had inserted the remains of some destroyed paintings, thus creating a chandelier that did not diffuse light, but shadow, so as not to disperse energy by going to cancel entropy. A 1988 work juxtaposed the ever-recurring themes of the passage of time and the quest for immortality with the relationship between the artwork and its surroundings. The work in question, exhibited at the Lia Rumma Gallery in Naples, resumed an earlier destroyed work, Mirror that Reflects Everything but Living Things, and consisted of placing a mirror in front of a painting in a semi-darkened room so that it reflected the work but not the viewers, hinting at the belief that art remains immobile, while man is transitory. Thus De Dominicis came closer and closer to solving the problem, identifying art as an immortal element, thus not the artist nor man.

During the 1990s, De Dominicis’ artistic production veers toward more stylized forms. Bold color combinations appeared in these years, such as black with gold, much loved by the artist, or red and black. In these years he used pencil very often, with unprecedented, highly expressive figurative results, such as sneering faces, hunched bodies and squinting eyes (the figures made between 1996 and 1997), or a couple joined in a single figure (1991). Also noteworthy are a series of large paintings made with white and gold, presented at the 1993 Venice Biennial, in which De Dominicis depicts the cosmos before the birth of heaven and earth, with an arrangement of planets and satellites that did not correspond to what was known and in fact finds its origin in the creation myth of Sumerian culture. In this way, De Dominicis presented another cosmos, in another time.

Where to see the works of Gino De Dominicis

One of the hallmarks of De Dominicis’s character was his refusal to have his works photographed. The motivation probably lay in the artist’s belief that this medium had less intensity than painting. Therefore, many works dating from the early period are handed down from testimonies of gallery owners and friends, but no visual records remain, except for a few exceptions.

In fact, De Dominicis granted some photographic testimonies that he carefully selected; this was the case, for example, with Tentativo di far formare dei quadrati invece che dei cerchi attorno a sasso che cadere nell’acqua or Seconda soluzione d’Immortalità (L’Universo è Immobile).

As for the presence of other works by De Dominicis in Italian museums, two works in graphite on panel, namely Untitled and With Title, from the mid-1980s are preserved in the GNAM - National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome.

Within the collections of the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte in Naples is Untitled (1996-97). Some works are, in addition, exhibited in the Castello di Rivoli, including Untitled (1967-69) and Untitled (Urvasi and Gilgamesh) from 1988. Some videos by De Dominicis are, finally, part of the video libraries of the GAM - Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Turin, in which is Tentativo di volo (1969) and of the Historical Archives of the Venice Biennale, in which is kept Videotape (1974).

|

| Gino De Dominicis, the artist against convention. Life, major works, themes |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.