Sculptor, architect, painter, scenographer: Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples, 1598 - Rome, 1680) was one of the great protagonists of seventeenth-century Europe and the artist with whom Baroque sculpture reached its highest heights. A great interpreter of the figurative culture of his time, Bernini was a daring and continuous experimenter, who along a career that lasted more than sixty years was able to innovate continuously, inspiring generations upon generations of artists, creating legions of imitators, and earning the attention and commissions not only of the popes for whom he worked and for the great Roman families (such as the Borghese, Barberini, Pamphilj, and Aldobrandini), but also of various European rulers who asked him for portraits all the time. He was thus an enormously successful artist.

Bernini’s works profoundly changed the face of Rome and helped make it the spectacular and multifaceted city we see today. His masterpieces are housed in all corners of the historic center, and one can hardly say one has really seen Rome unless one takes a Bernini tour, as Baroque Rome unmistakably bears his signature. Bernini was one of the leading figures in Baroque figurative culture, and he gave birth to a new taste: an art that was animated, dynamic, scenic, dramatic, and engaging (the name “baroque” perhaps derives from the French word “baroque,” itself a cast of the Portuguese “barroco” and the Spanish “barrueco,” both terms indicating a pearl of irregular forms: it was initially used by historiography with derogatory intent, since Baroque creations were seen as extravagant and bizarre).

With Bernini, moreover, a true civilization of the image was formed based on the persuasive power of art: a civilization that was born with the Church and spread to the rest of Europe, with the courts animated by the same propagandistic intentions as the Church. Moreover, man was no longer at the center of the world, as in the Renaissance: with Bernini and the Baroque artists, space expanded to infinity (think of the dilated perspective fugues of his architecture, or, to find a counterpart in painting, the great skies of Pietro da Cortona or Giovanni Battista Gaulli). An infinity that is a reflection of the scientific research of the time but is also the dimension of Providence, of which artists were called upon to give vision.

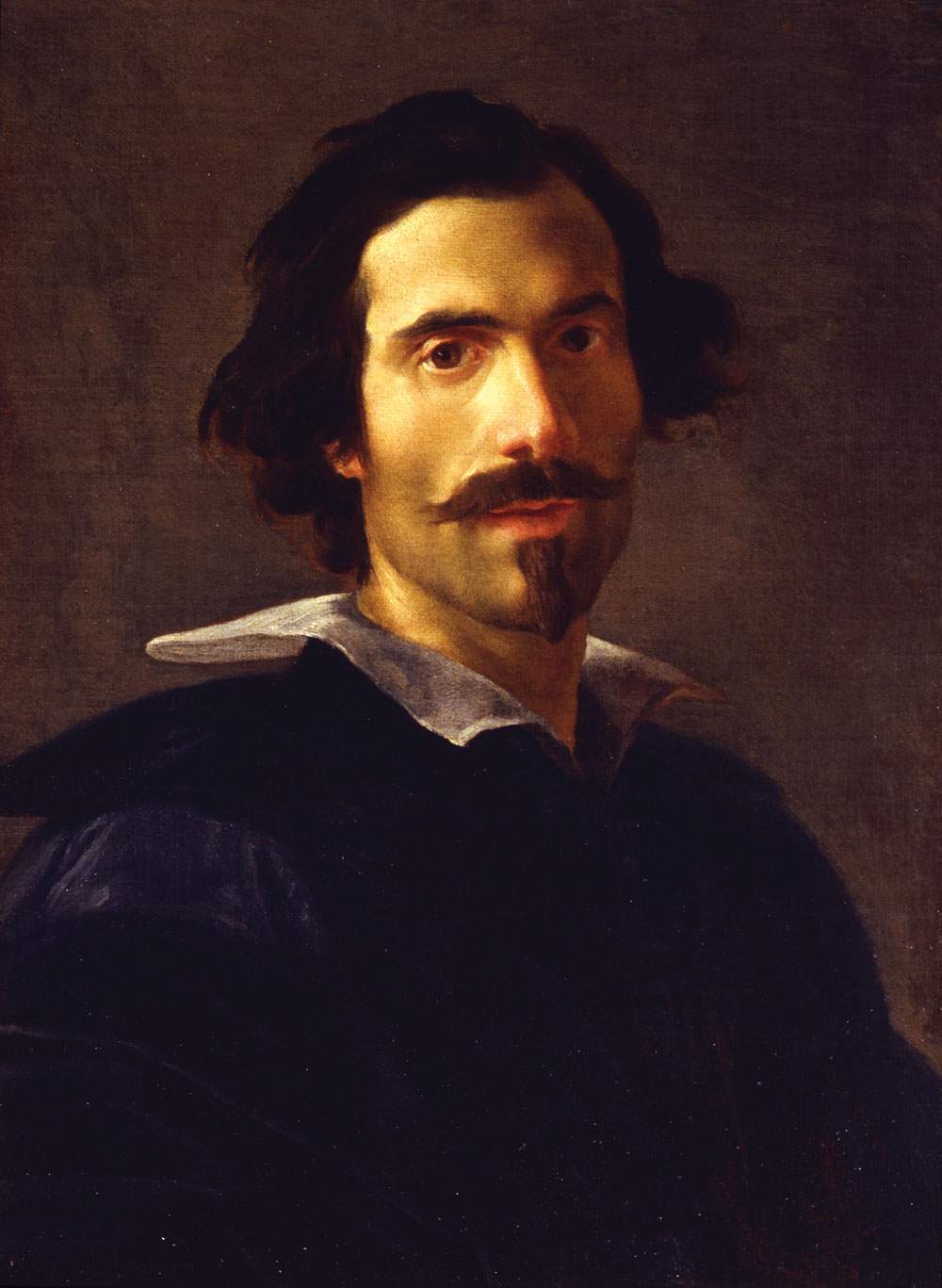

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Self-Portrait (oil on canvas, 62 x 46 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery, Vasari Corridor). |

Gian Lorenzo Bernini was born in Naples on December 7, 1598, to Pietro Bernini (also an important sculptor, originally from Sesto Fiorentino) and Angelica Galante, a Neapolitan. The artist spent the early years of his life in the Campania city, where his father was working at the time, and completed his apprenticeship with Pietro himself, whose collaborator he would later become. In 1606 the family moved to Rome, as Pietro was hired by Pope Paul V. As a teenager, Gian Lorenzo began to produce some independent works, such as the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence now in the Uffizi and the Saint Sebastian in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid. His qualities were immediately noticed by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, who in 1618 commissioned him to paint the first of the Borghese groups, theAeneas and Anchises, completed in 1619 (the Rape of Proserpine, theApollo and Daphne, and the David, on the other hand, date from 1621-1622, 1622-1625, and 1623-1624). In 1623 Cardinal Maffeo Barberini became pontiff under the name Urban VIII, and Bernini was appointed commissioner of the fountains in Piazza Navona despite his young age (he was only twenty-five), and upon his father’s death in 1629 he also obtained the post of Architect of the Waters. And also in 1623 Urban VIII commissioned him to design the canopy of St. Peter’s, which the artist would finish after about nine years of work.

In 1628, Bernini began making the funeral monument of Urban VIII, which would be finished in 1647, and the following year the artist, at the age of thirty-one, was appointed superintendent of the Fabbrica di San Pietro. The same pope entrusted him in the same year with the work of completing the Barberini Palace. In 1630 the artist was still burning the candle at the seams, and at only thirty-two he was elected Prince of the Accademia di San Luca. Instead, the ceber portrait of Costanza Bonarelli, his mistress, dates from 1636; she is the wife of Matteo Bonarelli, a sculptor from Lucca who was Gian Lorenzo’s collaborator. The artist discovers that the woman is also the mistress of his younger brother Luigi, and the relationship will end violently: the woman is scarred by one of the artist’s servants and Luigi is beaten to a pulp by Gian Lorenzo, who, however, thanks to the pope’s protection, will only get off with a fine. In 1639 Gian Lorenzo marries Caterina Tezio, by whom he will have eleven children.

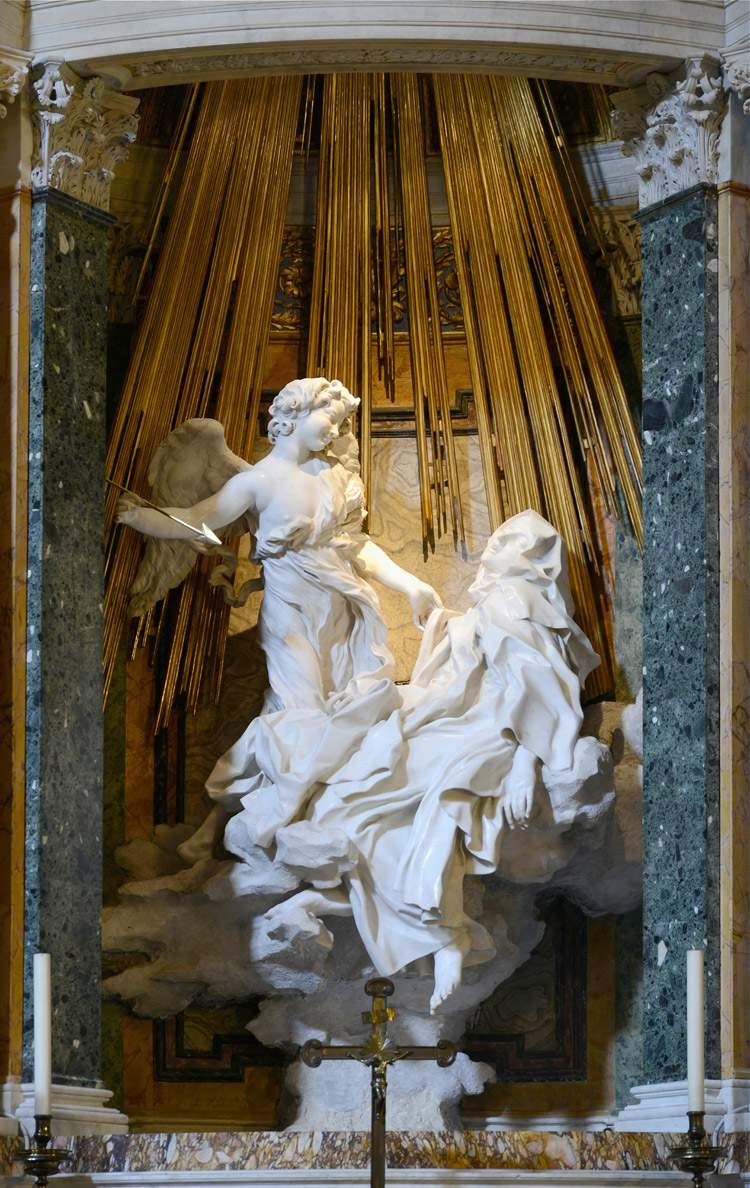

In 1642, for the Barberini family, Gian Lorenzo executed the famous Fountain of the Triton, and in 1644 The new pope Innocent X (born Giovanni Battista Pamphilj), who succeeded Urban VIII who had died the year before, entrusted the artist with the realization of the Fountain of the Four Rivers, despite the pope’s predilection for Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s historical rival, namely Francesco Borromini (so much so that it seems that in order to win the commission, Bernini resorted to a stratagem by having the project secretly delivered to the pope). It was precisely during the pontificate of Innocent X that one of the artist’s greatest defeats dates back to, when he was forced to demolish the bell towers of St. Peter’s at his own expense because of static problems: the débâcle alienated him from the pope’s favor, the artist felt disappointed, outraged and persecuted by his colleagues, and to redeem himself he executed for himself, with clear symbolic intentions, the Truth Revealed by Time, now in the Borghese Gallery. In 1647, for the Cornaro family, the sculptor began work on the spectacular Ecstasy of St. Teresa, which would be completed in 1652. In 1655 the new pope Alexander VII (born Fabio Chigi) commissioned him to make some sculptures for the family chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome, and the following year the artist designed the famous colonnade of St. Peter’s, which would be completed in 1665. Just in 1665 Gian Lorenzo is called to Versailles to prepare a design for the facade of the Louvre: however, his style is not liked by the French, so the artist returns to Rome after a few months. In France he succeeded in making only a bust-portrait of Louis XIV.

Back in Italy, in 1667 Pope Clement IX (born Giulio Rospigliosi) entrusted him with the creation of statues for Ponte Sant’Angelo, and four years later Bernini began work on one of his late masterpieces, theEcstasy of Blessed Ludovica Albertoni. In 1672 he began work on the tomb of Alexander VII, which would be finished in 1678. Gian Lorenzo Bernini died in Rome on November 28, 1680.

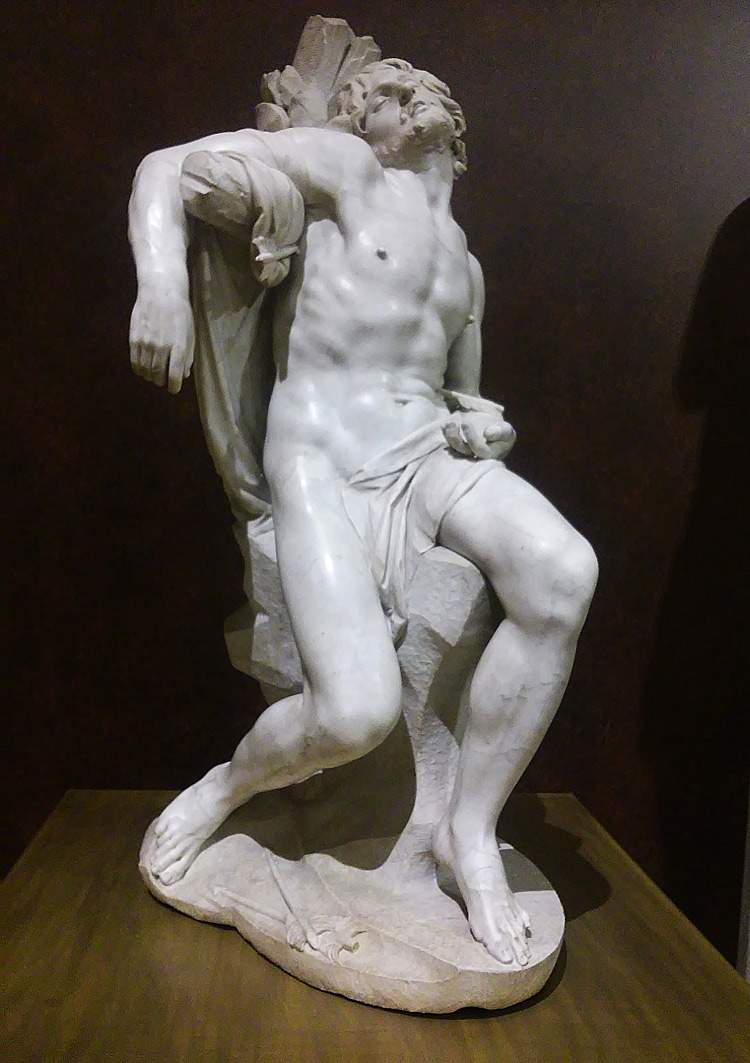

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Saint Sebastian (1615; marble, 98 x 42 x 49 cm; Madrid, private collection on deposit at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Rape of Proserpine (1621-1622; marble, 255 x 109 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Costanza Piccolomini Bonarelli (c. 1635; marble, 74.5 x 64.2 x 5 cm; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, La Verità svelata dal Tempo (1646-1652; Carrara marble, height 277 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese, inv. CCLXXVIII) |

To understand the themes and innovations inGian Lorenzo Bernini’s art, one might begin with theApollo and Daphne, a work from 1622-1623. The first theme is that of movement, which lies at the basis of Baroque aesthetics; we appreciate here the running of the god Apollo, who with one hand has by now grabbed the nymph, and the momentum of Daphne attempting to escape from the god, for a feeling of dynamism well rendered by the great skill with which Gian Lorenzo Bernini delineates the moving muscles and the twisting of the bodies. Then there is another element typical of Bernini’s poetics, namely the depiction of a very specific moment in the story, in this case the one in which Daphne’s transformation into a laurel plant begins with Apollo now unable to do anything about it: today we see the statue at the Galleria Borghese placed in the center of a room, a position that allows us to walk around the sculpture seeing it from several sides, but this was not Bernini’s intent, since the statue was originally placed in front of a wall and had only one privileged point of view (Bernini intends in fact to represent an action that takes place in a fraction of a second and can therefore be captured only at one point), and in particular this point of view was the one in which Apollo was seen from behind. Emotional involvement of the viewer is another characteristic of Baroque art, and this is one of the most engaging and theatrical works of seventeenth-century art, not only because of the excited movement, but also because of the contrasts between light and shadow that are created through the arrangement of the figures, and then also because of the study of expressions: We read on Daphne’s face a desperate cry in her last, successful attempt to evade the god, and on Apollo’s face instead the astonishment and disappointment at not having succeeded in his intentions and at having seen the transformation of Daphne into a laurel tree begin (we see how Bernini was able to communicate this idea to us by having Daphne’s fingers, both feet and hands, start roots and fronds with leaves, while her legs begin to transform into the trunk of the plant). These are motifs that Bernini developed in the aftermath of the Rape of Proserpine, another of his great early masterpieces(you can find an in-depth discussion of the work at this link).

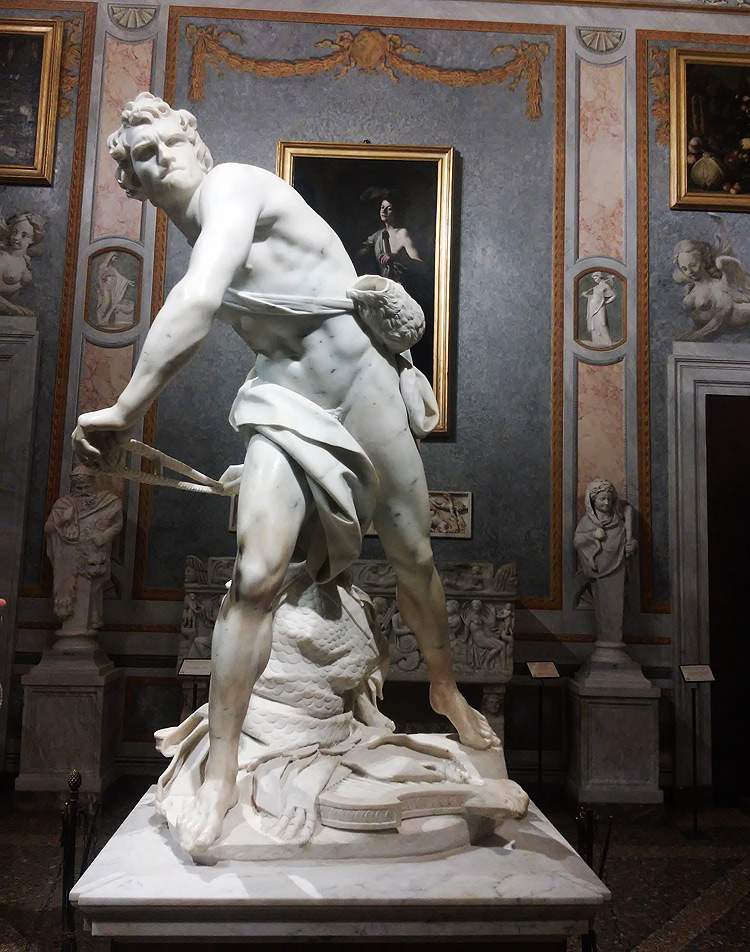

The David (1623-1624) is also captured at a very specific moment in history, and again the work was intended to be leaned against a wall, since the preferred viewpoint originally was only one, although in this case we do not know for sure which one it was (several hypotheses have been made about this). This aspect of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s art is even more evident here due to the fact that David is depicted at the instant he is about to throw his stone. The approach, however, is quite different of Michelangelo’s David, animated by a different tension: there, the moment of action was suggested by the tension of the muscles and it was the moment when David began to throw the stone (thus an earlier moment than the one described by Bernini, in which David is now about to set off the stone toward Goliath). This is a figure in full motion, following an almost spiral rhythm, caught in a climax of the story, a great masterpiece of Baroque art in which as we have seen the main intent is precisely to suggest movement and engage the viewer. Also dating from 1623 is the commission of the Baldachin of St. Peter’s, from Pope Urban VIII: this is an imposing structure almost thirty meters high that towers above the high altar of St. Peter’s Basilica (it was finished in 1634). The artist recovers the traditional type of the baldachin that had distinguished religious art in Italy for centuries, but he revisits it profoundly because in accordance with Baroque aesthetics the artist imagines a structure capable of fusing together different types of art(architecture, sculpture and painting), since one of the main characteristics of Baroque art lies precisely in the fusion of different art forms, which also happened punctually in painting especially in the large scenic frescoes where the painted scene depicted fake architecture that broke through vaults and walls and where it was not uncommon to find sculptures painted in such a way that they could look real. The contamination, in the St. Peter’s baldachin, can be seen in the layout, which almost resembles a temple, is decorated with sculptures on top, and the details, such as the ornaments on the twisted columns, show a taste for the decorative with a distinctly painterly flavor. Even with the baldachin Bernini shows that he is seeking the full emotional involvement of the observer inside the basilica, because underlying the baldachin there is a profound study of the various light conditions at different times of day, which made certain elements of the work stand out (in the 1960s, Bernini had this to say that “things never appear for what they are, but in relation to the things they have around them, which modify their appearance”).

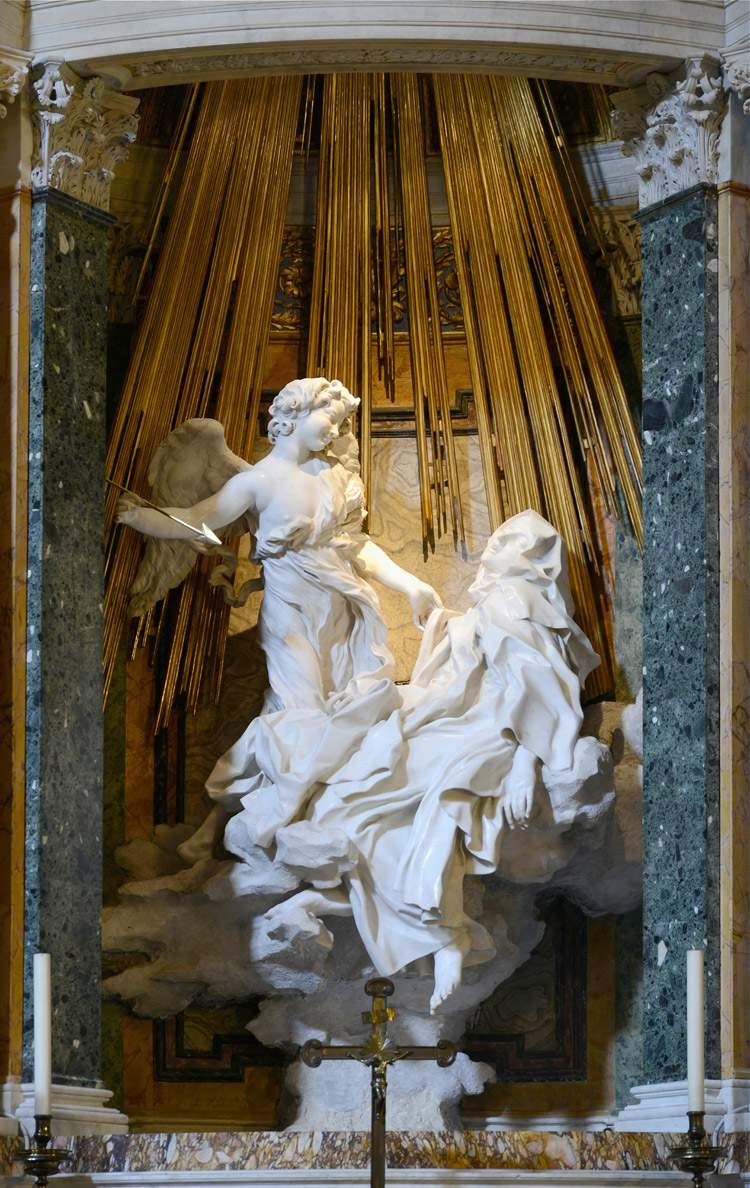

These elements return in a masterpiece such as theEcstasy of St. Theresa, perhaps Bernini’s most spectacular and engaging work: it was made between 1647 and 1652 and is in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome, in the Cornaro Chapel. It is a complex work founded on the fusion of the arts (Bernini’s group dialogues with the architecture of the chapel and the painted vault) and with great pathos recounts a mystical ecstasy of the Spanish saint. As with St. Peter’s baldachin, Bernini studied deeply the light conditions, which led him to insert in the chapel a hidden window that is practically above the main group and closes at the top that small semicircular apse that houses St. Theresa and the angel, in order to let natural light filter in to illuminate the whole group, creating reflections even on the magnificent golden rays that stand behind the two figures and symbolize divine light (at this link you can find a detailed in-depth discussion of the work).

Finally, talking about Bernini’s art also means thinking about his splendid fountains, which adorn Rome, such as the Fountain of the Triton and the Fountain of the Four Rivers. In the former, dating from 1642-1643 and commissioned by Urban VIII, two dolphins hold the valves of a large shell on which the triton finds space, blowing into its bucina, from which water gushes forth. These elements fuse together resulting in a sculpture that resembles an architectural structure (the dolphins look like a column, the shell a capital). The Fountain of the Four Rivers (1648-1651), made with extensive workshop competition, depicts the personifications of the four rivers, which symbolize the known world in its continents, and were made by Bernini’s collaborators according to the original design (the Danube by Antonio Raggi, the Nile by Jacopantonio Fancelli, the Ganges by Claude Poussin, the Rio by Francesco Baratta). The Fountain exalts another of the founding elements of the Baroque, namely the taste for highly scenic apparatus: Bernini, here, reaches one of the heights of his theatricality, thanks to a combination of several factors such as the upward thrust, the effects created by light and water, the often daring positions of the various elements of the fountain, and the curious appearance of many details (the animals, for example). Bernini was, in essence, the ultimate interpreter of Baroque taste in sculpture, dictating tastes and trends in seventeenth-century sculpture.

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Apollo and Daphne (1622-1625; marble, 243 cm excluding base 115 cm, base 130 x 88 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, David (1623-1624; marble, 170 x 103 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Theresa (1647-1652; marble and gilded bronze, h. 350 cm; Rome, Santa Maria della Vittoria). Credit |

|

| The Albertoni Chapel |

To learn about Bernini’s art, one must travel to Rome, the city where all the major masterpieces of the great Tuscan-born artist are concentrated. From the Borghese Gallery (which houses the four “Borghesian groups,” namely theApollo and Daphne, the Rape of Proserpine, Aeneas and Anchises, the David, and several important works such as the Amaltean Goat and the Truth Revealed by Time) to his fountains that can instead be admired for free in the city’s squares (the Fountain of the Triton and the Fountain of the Bees in Piazza Barberini, the Fountain of the Four Rivers and the Fountain of the Moor in Piazza Navona, the Fountain of the Barcaccia made as a collaborator of his father Pietro), passing through the churches: in Santa Bibiana there is a statue of the saint to whom the house of worship is dedicated, in Santa Maria della Vittoria one can admire theEcstasy of St. Teresa, in Santa Maria Sopra Minerva for the spectacular but little-known monument to Maria Raggi, in Santa Maria del Popolo where the groups of Daniel and the Lion and Habakkuk and the Angel are preserved, in San Francesco a Ripa for the celebrated Ecstasy of Blessed Ludovica Albertoni. A visit to St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican is then a must to admire the baldachin, the statue of St. Longinus, the monumental tombs of the popes, and the Capitoline Museums where the great statue of Urban VIII towers and where the marvelous Medusa can be admired.

Some of Bernini’s masterpieces, however, can be admired outside Rome. In Florence, the Museo Nazionale del Bargello holds one of the artist’s most moving portraits, that of Costanza Bonarelli. The Uffizi, on the other hand, preserves an early work, the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence, from 1617. In Modena, the portrait of Francis I can be admired at the Galleria Estense, while the monument to Pope Alexander VII, Saint Jerome, and Saint Mary Magdalene can be seen in Siena Cathedral. Outside Italy, on the other hand, there is a fundamental Bernini intervention on an ancient statue: theHermaphrodite in the Louvre in Paris (Bernini sculpted the mattress). Other museums scattered around the world hold busts and portraits by the Tuscan artist.

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini: life, works, baroque masterpieces |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.