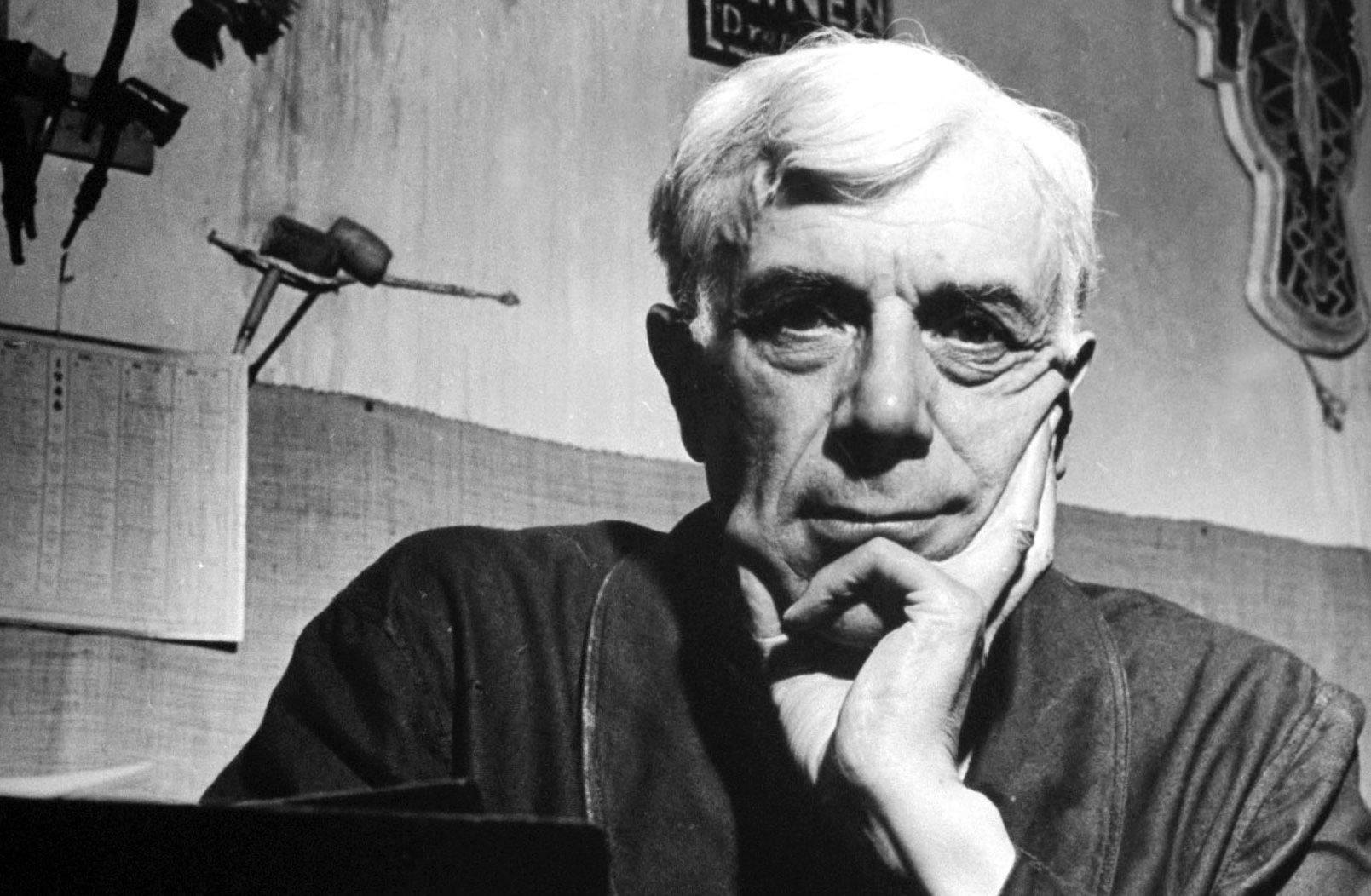

Georges Braque (Argenteuil, 1882 - Paris, 1963), great French painter and sculptor, is considered, along with Pablo Picasso, the progenitor of Cubism. Braque and Picasso met in 1907, and by frequenting the Cubist artist Braque assimilated many notions, for example he delved into ’African primitive art, and mastered the various phases of Cubism, moving from the bright colors and a Fauves style of his early work to the simplification of nature into shapes, colors and lines.

He was a very prolific painter and tried his hand at various experiments, even making collages for a time. Often the cubist works, especially the analytical ones, required a very demanding effort indeed on the part of the viewer to understand the real subject represented, which was often revealed only by reading the title of the work in order to more accurately imagine the source image.

World War I conditioned his relationship with Picasso, and upon his return from the front Braque settled back in Normandy, where he devoted himself to landscape paintings while resuming painting figuratively.

Georges Braque was born in Argenteuil on May 13, 1882 to Charles Braque (painter and decorator) and Augustine Johannet, but spent his childhood and youth in Le Havre, Normandy. He began his art studies here, attending the Evening School of Fine Arts from 1897 to 1899, after which he moved to Paris. He began a practicum as an apprentice to a master decorator, and obtained his license in 1901. In 1902 he enrolled at the Académie Humbert, where he studied until 1904 and met among his fellow students the avant-garde artist Francis Picabia. He continued his training at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, beginning to produce figurative works akin to the modes of the Fauves and Henri Matisse.

The year that marked a turning point for Braque was 1907, when he visited a Paul Cézanne retrospective within the Salon d’Automne. The Salon in question was an exhibition that contrasted not only with the classic Salon at the Louvre but also with all other Salons known to date, e.g., the Salon des Indépendants, because of its specific desire to accommodate avant-gardes considered “anti-academic.” It was here that the Fauves themselves had exhibited their works for the first time in 1905. Braque’s visit to the retrospective devoted to Cézanne is a moment that will condition, on closer inspection, all French art of the 1900s, as this occasion Braque met Pablo Picasso. It was here that the foundations were laid for the birth of Cubism.

Picasso at that time was working on Les demoiselles d’Avignon, studying a lot of so-called “primitive” African art. Braque became fascinated by this art and began to delve into it as well, continuing to work more and more frequently together with Picasso. The personal and artistic friendship that arose between the two artists led to new elaborations of Cubism and experiments that lasted until 1914, when the relationship suffered a setback as Braque was called to fight in World War I. During the conflict he was wounded and spent his convalescence returning to live in Normandy, resuming painting in full autonomy veering back toward figurativism. He received the Feltrinelli International Prize for the Arts awarded by the Accademia dei Lincei in 1958. Georges Braque died in Paris on August 31, 1963, and was buried in the marine cemetery of Varengeville-sur-Mer in Normandy, so called because it is located directly across from the sea.

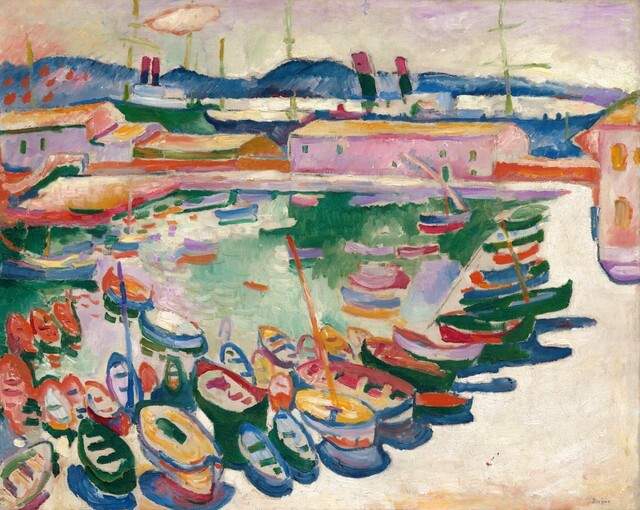

Braque was a rather prolific and multifaceted painter, often producing different versions of the same subject. Various phases can be recognized in his art, from Fauve to formative cubism, then to analytic cubism and finally back to figurativism. By the time Braque met Picasso in 1907, his painting was undergoing a fascination with the Fauves and, therefore, with the bold juxtapositions of bright colors that anticipated expressionism. The Fauve period lasted for a couple of years and was characterized by geometrically rendered landscapes, as shown in the painting The Olive Tree (1906), in which the forms are soft and filled not by outlines but by bright colors that do not adhere to reality. Also in the same vein is The Port of La Chotat (1907). Braque had visited of the real this town in a series of short trips he made with his artist friend Othon Friesz, also a Fauvist painter, between 1906 and 1907. The two artists visited: Antwerp, Belgium; L’Estaque twice; and finally La Chotat itself in the late spring of 1907, devoting themselves to intense painting sessions during which Braque was able to assimilate all the elements of the Fauves’ style.

The harbor is indeed a typical subject of these painting sessions, and in this particular case he portrays a small town with a small harbor (visible in the lower part of the painting) dominated by the so-called dry dock, a structure set up for the repair of large ships out of the water, and indeed in the background of the work one can see precisely two large ships, contrasting with the small boats anchored in the foreground. In this painting, as in the others of the period, the golden hue that characterized Braque’s works is accentuated precisely because of the time spent in the warm light of southern France.

During the same period, Braque offered several landscapes from L’Estaque (1908), a location on the Gulf of Marseille, devoting himself to “Formative Cubism,” or “Protocubism,” a phase of the artistic current in which forms are reduced geometrically into pure volumes. Still lifes, figures and landscapes are favored, as is the case in the work in question. The hilly landscape of L’Estaque is rendered through the reduction of natural elements into highly simplified geometries, such as circles, lines, and curves, always with very vivid colors (unlike other proto-Cubist paintings, in which usually tended monochromatic colors in the brown range were used) thus keeping present his predilection for Fauvism.

Braque sent seven paintings dated to this period to the 1908 Salon d’Automne, but five of them were rejected. The French poet Apollinaire reported that it was on this occasion that the term “cubism” was officially born, derived from a phrase that Henri Matisse, a member of the jury of the Salon in question, uttered in a derogatory way to define the works viewed. Later, the painter Louis Vauxelles returned to talk about “paintings made in cubes” in regard to some of Paul Cézanne’s works, and Braque was impressed by the term and officially began calling his and Picasso’s paintings “cubist” works.

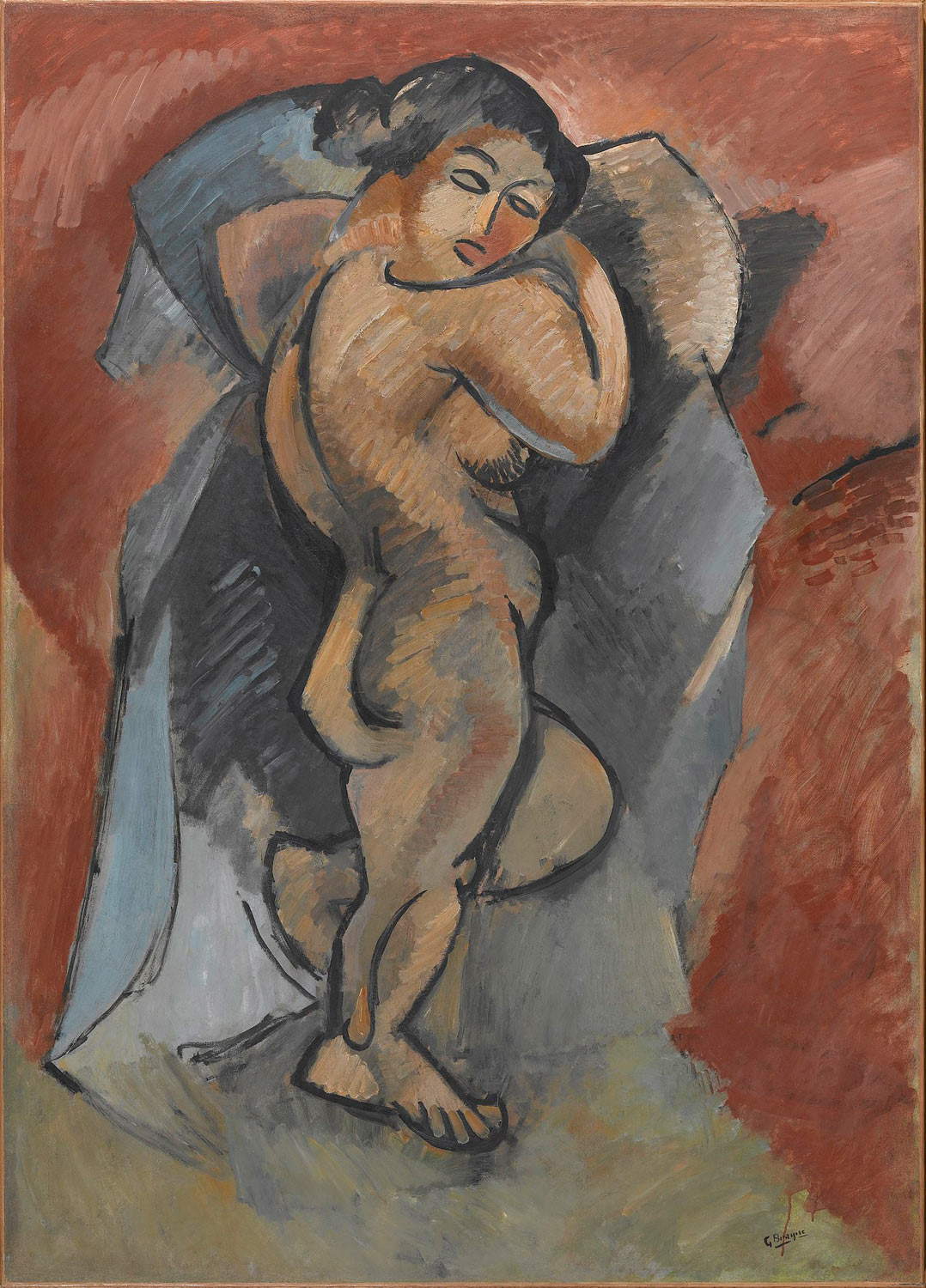

Braque’s exploration of ’primitive art, which arose from his association with Picasso, led him first to skim the colors down to a focus on green and brown, and then to reinforce the use of geometric volumes, trying to recreate space without resorting to perspective or chiaroscuro. For example, in the 1908 work Grande nudo (Grand nu) , the volumes of the body are rendered with quick, broad brushstrokes and are defined by very thick contour lines. Braque also used the same principles of volume delineation as in the Grand nude in his landscape and still life works. Soon after, however, beginning in 1909, together with Picasso he would arrive at a new phase of Cubist painting that resulted in “Analytical Cubism”, characterized by the achievement of geometric and chromatic decomposition of the scene through the identification of primary forms and pure colors chosen by an analytical-inductive method, whereby the viewer is asked to make an intellectual effort to observe the painting and reconstruct the subject without using the simple mechanisms of sight. Another typical feature of Analytic Cubism is the union of perspective planes on the single surface of the painting, as seen in Violon et Palette (1909) and The Mandola (1910), two paintings in which Braque’s fondness for musical instruments, which he surrounded himself with and which he often portrayed while managing to suggest the vibration they produce when played, is also present.

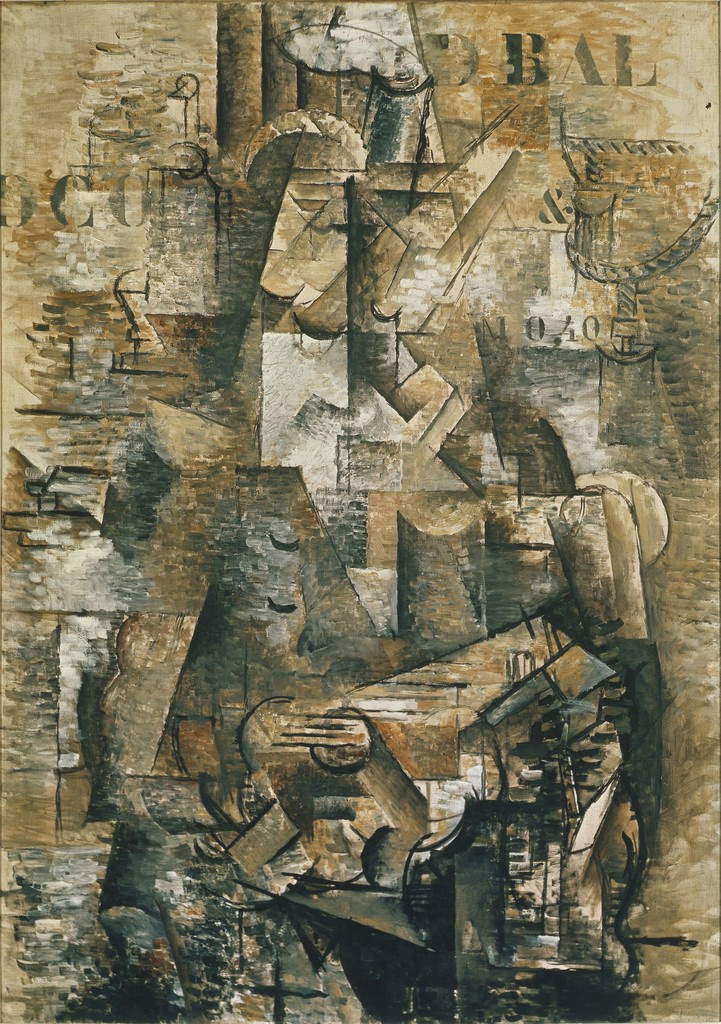

Experimentation with volumes, however, led to very complex outcomes, and Braque’s works dated between 1909 and 1911 are hardly decipherable to the outside eye. From 1911, then, he began to introduce letters and numbers into his works so that the viewer could have references that were recognizable, as happens in Le Portugais (1911). The following year he also began to master the technique of collage, which he used with the intention of describing an object through dissociation of forms and colors, as happens in Woman with Guitar (1913) in which the painted surface is enriched by the insertion of newspaper clippings, a perishable and above all poor element deliberately inserted as a reference to the temporariness of art.

In Man with a Violin of 1912, Braque’s desire to stimulate the viewer’s imagination in such a way as to lead him to notice aspects of reality that elude the first glance finds maximum sublimation. Among other things, this methodology also aligned with the advances made by science and in particular the study of physics, emphasizing precisely how there are mechanisms and aspects that are not immediately visible. Clearly, this type of analysis takes a non-objective direction in Braque’s painting, as the precise intent is to represent an aesthetic ideal of the chosen subject. It thus becomes non-immediate to be able to accurately identify all the elements in the painting, for example, at the bottom there are also included scores, suggested only by the lines of the staff devoid of notes.

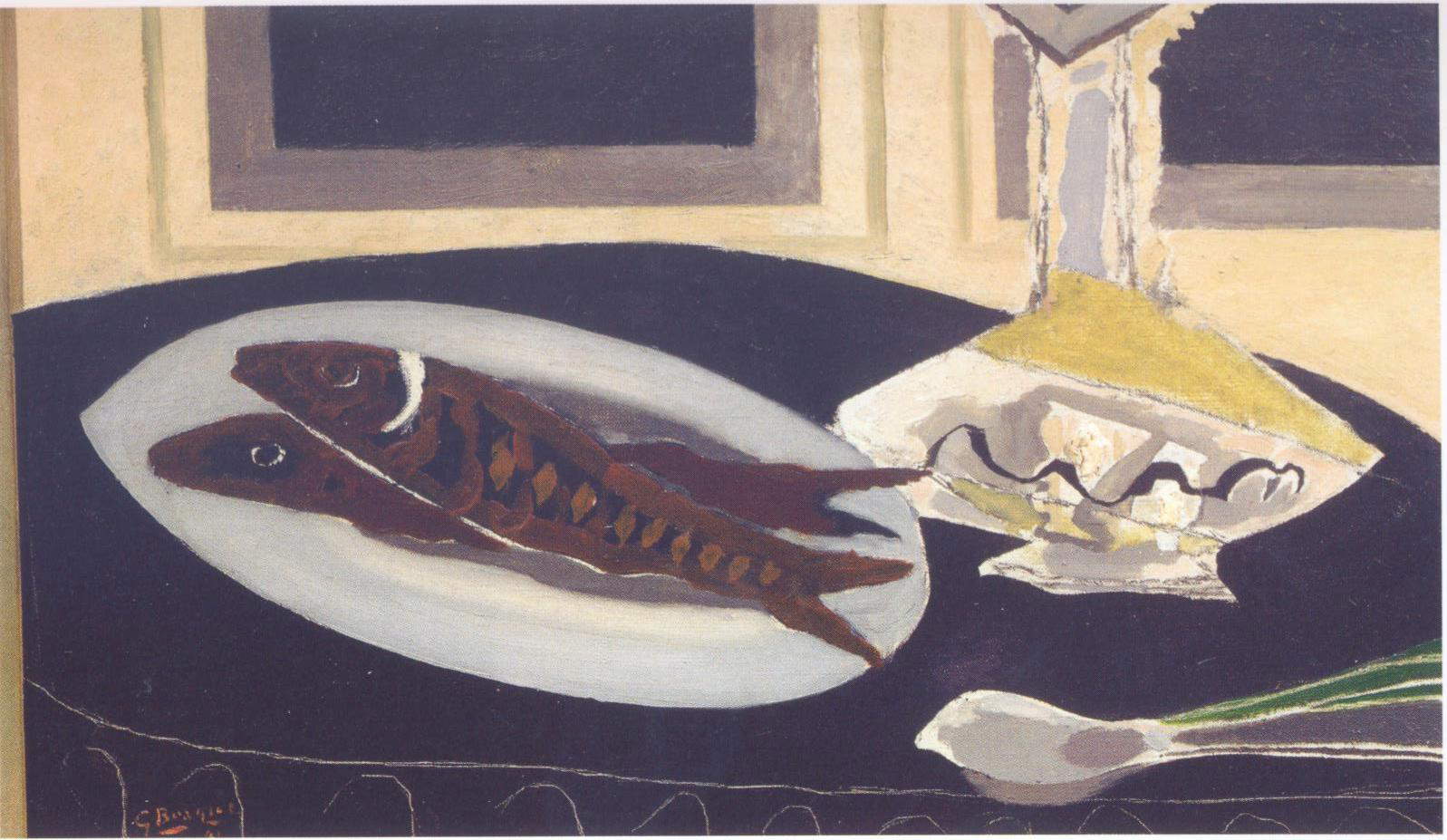

Upon his return from World War I, Braque took to working independently, developing a more personal style and again using bright colors to the point of repurposing the human figure, particularly after his move to the Normandy coast. This is a Cubism defined as “curvilinear,” which will nevertheless always remain present during the various “oscillations” on Braque’s figurativism, who between 1922 and 1929 moved closer to the natural form of objects, only to move away from it again in 1930 and approach it again in 1940. Dating from this period are the series of Ateliers (1948-1955) and Birds (1955-1963), The Jug and the Fish (1941), and The Billiards (1943). During this period he also made some decorative works such as the sculpture of the tabernacle door of the church in Assy in 1948 or the decoration of the ceiling of the Etruscan room at the Louvre Museum from 1952 to 1953.

Braque’s works are in a very large number and include several versions of the same subject, so the following list will mention the best known, most famous works that marked an important stage in his painting activity. In France, the painter’s native country, the largest nucleus of works is preserved in the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the exhibition space that presents the majority of French avant-garde works(Impressionists, Cubists etc.). These include Still Life with Violin, 1913, numerous paintings set at L’Estaque, Grand nou (1907) and many others. Also at the Centre Pompidou are L’Olivier at L’Estaque (1905-06), The Jug (1941) and The Billiards (1943) and other works. In the Louvre Museum, however, is Still Life with Bottle (1910-11).

In other European countries, Braque’s works can be found in Switzerland, including Houses at L’Estaque (1908), one of Braque’s most famous paintings, which is housed in the Bern Museum of Art, and there is also Man with Violin (1912) which is in Zurich in the E.G. Bührle; we also find works in Germany, including The Olive Tree (1907) in the Folkswang Museum in Essen and Le Portugais (1911) in the Kunstmuseum in Basel; and finally in Prague, where Violin and Clarinet (1912) is in the National Gallery along with other still lifes.

There are, in addition, several works in the United States, such as The Port of La Ciotat (1907) in New Orleans in the Art Museum and Violon et Palette (1909) in the Guggenheim Museum in New York. In the two most important museums in New York, the MoMa - Museum of Modern Art and the Met - Metropolitan Museum of Art, there are, among others, Man with Guitar (1912) in the MoMa, while Woman Carrying a Basket of Fruit (1923) and Still Life with Guitar on a Pedestal (1924) in the Met.

There are also numerous works by Braque in Italy: in Milan in the Museo del Novecento there is Port miou (1907; in Rome a Still Life with a Clarinet, a Fan and a Bunch of Grapes at the GNAM - Galleria Nazionale di Arte Moderna; and finally in Venice The Clarinet (1912) and Fruit Bowl with Grapes (1926) in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection.

|

| Georges Braque, life, works and style of the great cubist painter |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.