Filippo de Pisis (Luigi Filippo Tibertelli de Pisis; Ferrara, 1896 - Milan, 1956), initially dedicated to a career as a writer and the author of several essays on artistic themes and in particular on metaphysical painting of which he was particularly fond, later decided to pursue his career as a painter during an important period he lived in Paris.

He had several friendships and acquaintances in the cultural circles of Bologna, Rome, Milan and Paris: among the artists he frequented were Giorgio de Chirico and Alberto Savinio, who were two very important figures in his career. As an artist, he used the languages of the early twentieth-century avant-garde to update common subjects such as still lifes, vases of flowers and landscape paintings, with innovative results.

Filippo de Pisis, born in Ferrara on May 11, 1896, came from a large family of noble origins: in fact, he was the third of seven siblings born from the union between Count Ermanno Tibertelli and Giuseppina Donini. He had a very close artistic relationship with his sister Ernesta, older by a year, with whom he collaborated four-handedly on several writings. As a child he studied at home with several tutors, and later confirmed his inclination for literary study by attending the high school gymnasium in Bologna. In the course of his education he had the opportunity to study drawing, having as teachers Odoardo Domenichini and the brothers Angelo and Giovanni Longanesi.

By 1904 de Pisis had moved with his family to Palazzo Calcagnini in Ferrara, the guests of Count Giovanni Grosoli Pironi, who proved to be a key figure in de Pisis’ entry into local cultural circles. In addition to literature, a great passion of de Pisis wasentomology: in fact, even as a child he used to collect shells and butterflies in a very rigorous way; moreover, he took care of a very detailed herbarium, which today has been donated to the University of Padua.

De Pisis’s youth in Ferrara was marked by important encounters that influenced his artistic life. By 1915 he had befriended Giorgio de Chirico and his brother Alberto Savinio, while in 1917 he met Carlo Carrà, thus coming into contact with the latest avant-garde currents and being greatly impressed by metaphysical painting. At that time, de Pisis still considered himself totally a writer and saw painting as a side activity. His friend de Chirico introduced him to Ardengo Soffici, inviting the futurist artist to read de Pisis’ writings, which he considered worthy of esteem despite not failing to call the young man “strange.” As a young man, indeed, de Pisis had a tendency to dress whimsically and to be noted for an undoubtedly precocious intelligence for his age and vast culture, which, as many sources report, he often flaunted. Once he graduated from high school, de Pisis continued his studies at the Faculty of Letters at the University of Bologna. He also engaged in epistolary conversations with Giovanni Pascoli and Gabriele d’Annunzio, and was a great fan of Giacomo Leopardi.

The conclusion of De Pisis’s university studies coincided with the outbreak of World War I, from which he was excused because of his health condition. He thus decided to travel and then move to Rome. In the capital, de Pisis entered the intellectual and artistic milieu, widening his circle of acquaintances, which at that point also included Giorgio Morandi, Giovanni Comisso and the Futurists Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Carlo Carrà. He organized his first solo exhibition in 1920, which, however, turned out to be a failure. He initially embarked on a teaching career in middle school and high school, partly in order to make up for financial hardship, yet he continued to feel that his path was writing. He frequently collaborated with avant-garde magazines such as La Voce, Lacerba and the Bolognese Brigata, and wrote metaphysical essays.

In 1925, after caring for his dying father in Ferrara, he moved to Paris and remained there for fourteen years, which determined the turning point in his career as an artist. During these years he got to know Édouard Manet, Camille Corot, Henri Matisse, the Fauves group, Pablo Picasso, George Braque, and writers Italo Svevo and James Joyce. The following year he organized his first solo exhibition in Paris, which was presented by De Chirico. Together with him, his brother Savinio and artists Massimo Campigli and Mario Tozzi he established the group of so-called “Italians of Paris.” For a period, between 1926 and the years immediately following, he exhibited his works together with the Gruppo Novecento of Margherita Sarfatti and others.

Between 1929, the year in which, moreover, he lost his mother, a circumstance that caused him great upheaval, and 1939, De Pisis had participated in several exhibitions in Milan, Rome, Venice and London, the city where he lived for a time. Unlike the first exhibition in 1920, these participations were very successful. The symptoms of neurasthenia, which he was diagnosed with as early as 1904, began to worsen in 1940. He thus decided to return to Italy for good and settled in Milan, except for a stay in 1944 in Venice to study the painting of the Venetian masters of the 18th century. He also spent a period in Rome to study 18th-century painting in depth. The results of his studies led him to develop highly successful works, which were acclaimed especially at the Venice Biennales of 1948 and 1954. However, his health deteriorated inexorably, preventing him from painting and writing. He finally died in Milan on April 2, 1956.

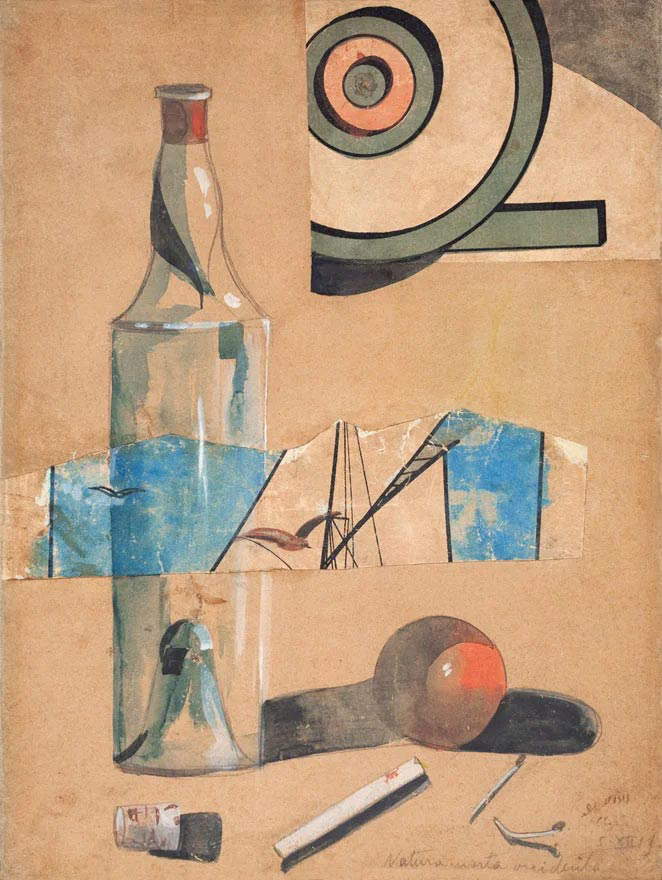

Initially de Pisis approached painting exclusively on a theoretical level, writing a series of articles in several important magazines of the time such as Valori Plastici and attending art conferences with various contributions. After some artistic beginnings dated to 1916, mainly watercolors called Collages because of the presence of a pair of extraneous strips attached to the canvas, and following his meeting with De Chirico and Savinio, de Pisis assimilated the metaphysical style that he brings back in some works of the early 1920s. One of his earliest early works, L’ora fatale (1919), is in effect a tribute to the metaphysical painting of his friend de Chirico.

The event in de Pisis’s life that turned out to be decisive for his artistic production was the period he spent in Paris. Coming into contact with the most interesting exponents of the avant-garde movements of the time, de Pisis took to painting still lifes, cityscapes and stays in Cortina, Cannes and Gascony, male nudes and hermaphrodites. In these Parisian works, a full-bodied brushstroke emerged, which went on to infuse movement and dynamism into the painting. de Pisis expressed in these works all his fascination with seventeenth-century painting and the French avant-garde, between Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, confirming his tendency to take, assimilate and make his own various characteristic elements of the great masterpieces of the past and the best of contemporary works. Gino Severini, in presenting de Pisis’s paintings at the 1932 Venice Biennale, describes them by speaking of "the Impressionists’ gaucheness,“ diluted by a ”skillfully and sensitively contrasted local tone." Among the works from this period is Natura morta con nudino e vino rosso (Still Life with Nudity and Red Wine ) dating from 1924. Regarding male nudes, the painting Piccolo Bacco (1928) is included, as well as de Pisis’ numerous drawings and watercolors on the subject. The protagonists are rendered with a very synthetic stroke, in positions that are often explicitly erotic and of abandonment to pleasure. Much fortune was also had by the subjects of marine still lifes, for example Natura morta con scampi (1926) a work with which de Pisis offers his personal contribution to new reflections in metaphysical and surrealist painting, by means of an obvious instability between the objects in the foreground and the background, to deliberately arouse a feeling of disorientation. Also in reference to metaphysical painting, significant were his statements in the article The so-called ’metaphysical art,’ published in 1938 in Emporium magazine, in which he had attempted to attribute to himself a role as a forerunner of the current, on a par with De Chirico.

In 1926, de Pisis exhibited the works Interno tragico, Campagna ferrarese and Campagna del suburbio at the I Mostra del Novecento italiano, with which he would continue to exhibit for a number of years despite the fact that his stylistic signature was distant from the group. Once back in Rome, de Pisis devoted himself mainly to still lifes and especially scenes with flowers, which became his favorite subjects. In 1934, moreover, an exhibition entitled “Fleurs de De Pisis” was mounted at the Galerie des Quatre Chemins that focused precisely on works with a floral theme. These include Gladiolo fulminato (1930), in which the brushstroke is so full-bodied and thick, approaching the achievements of Édouard Manet, as to achieve an effect of pure color. In De Pisis there is also a particular taste for effect gimmicks, through luminous colors that are often used as an enhancement of “trompe-l’oeil” effects.

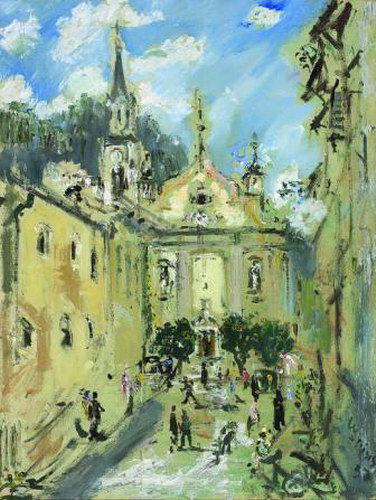

During his months in London, on the other hand, de Pisis had the opportunity to study in depth the landscapes of William Turner and also made himself a protagonist on the streets of London, where he used to attract the curiosity of passers-by while he was intent on painting particular city views, beginning to introduce a certain nervous visual fragmentation typical of some of the landscape paintings that are dated to the 1930s.

De Pisis’s participation in 1935 in the II Quadriennale nazionale, where he exhibited nineteen paintings, including Landscape in Gascony, Still Life with a Jay, and Figure in a Light Interior, aroused some reservations, especially about an alleged ease of execution that some critics had identified in some works. Generally, in the works of the 1930s, the earlier experimentation with compositional planes is lacking. Probably, however, as we read in the words of the critic Paul Fierens in a monograph he dedicated to De Pisis in 1937, in these years there was a gradual maturing toward a more essential expressiveness, but no less emotionally felt.

In 1939 he returned to the III Roman Quadrennial presenting Composizione and Notte di luna, and took second place at the I premio Bergamo with La chiesa di Cortina. Also in the same year de Pisis made a donation of twelve paintings to the GNAM - National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome, including several portraits, one of the most frequent themes of the period, partiularly of elderly and derelict subjects, e.g. Old Cadore Man (1942). During the years of World War II and his relocation from Milan to Venice because of the bombings, de Pisis’s painting and exhibition activity did not come to a halt and, indeed, he had good sales of his paintings, precisely because of the presence in Venice of many industrialists and wealthy landowners who had taken refuge there hoping that the lagoon city would be spared from the attacks. de Pisis also obtained several lithograph commissions for luxury publishing projects, including Marcel Proust’s Sojourn in Venice for Edizioni del Cavallino (1945) and Catullus’s Carmi for Hoepli (1945).

In the postwar period, however, his politically disengaged painting in the heyday of neorealism was the subject of controversy from some of the more politicized critical figures, yet this episode did not dent De Pisis’s commercial success, so much so that a market for fakes even developed. He eventually had to slow down his artistic activity because of his deteriorating health, and one of his last known works is Natura morta con calamaio (Still Life with Inkwell ) of 1952, in which he demonstrates both a further simplification of brushstrokes and further experimentation with transparencies and the use of white, and Natura morta marina con la penna (Still Life with Pen ) (1953).

In Filippo de Pisis’s hometown of Ferrara, a museum named after him, the Museo Filippo de Pisis, was opened in 1998 following a major anthological exhibition organized to mark the centenary of the painter’s birth. The nucleus of works was quite substantial, more than two hundred, and showed the entire artistic career of de Pisis from his early works to his last works.

Another substantial group of works can be found in Milan, the city where the artist lived for some periods. L’ora fatale (1919) is at the Fondazione Antonio Mazzotta, Milan, while a large group of works is preserved at the Pinacoteca di Brera, including Natura morta con le uova (1924), I pesci sacri (1924), Natura morta marina con scampi (1926), Natura morta marina con la pavoncella (1927), Parigi con la fabbrica (1927), Grandi fiori (1930), San Moisè (1930), Still Life with Fruit Basket (1935), The Peonies (1936), Flowers at the Window (1938), Still Life with Flowers and Bottle (1938), Flowers in the Glass and Book (1945), Portrait of a Woman (1950), Marine Still Life with Pen (1953).

Also in Milan, L’uomo delle stelle (1924), Paesaggio di Lers (1936), Zingari (1940) can be seen at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna. Other works by de Pisis are also kept at the Museo del Novecento in Milan. In another important city for the artist, Rome, there are some of his works at GNAM - National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art.

In Italy, other important museums preserve de Pisis’s works, including The Archaeologist (1928), at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Genoa, and then again among the institutions that preserve his works are the Museo d’Arte Moderna Ca’Pesaro in Venice, the MAGI ’900 in Pieve di Cento, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Palazzo Pitti in Florence, the Museo Civico - Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Torni, and the Fondazione Biscozzi Rimbaud, Lecce

Abroad, you can see his works in Paris, where he lived for a long time, specifically at the Centre Pompidou and Musée d’Art Moderne. Other works are kept in Cologne, at the Ludwig Museum, and in the United States, at the Cincinnati Art Museum.

|

| Filippo de Pisis, metaphysical painter and writer. Life, works, style |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.