Fauvism, the color revolution. History and style of the Fauves

Fauvism, from the French “Fauvisme,” was one of the first European painting movements of the 20th century, which followed and renewed the technical experimentation and research of Postimpressionism of the late 19th century. Arising in France from a diverse group of artists, the movement was short-lived, from 1905 when it was formalized during the Salon d’Automne at the Grand Palais in Paris to about 1907, although it established some of the most important artistic changes of the 20th century.

Although the group never produced a manifesto with a common aesthetic or political program, the painters known as the Fauves ( “beasts” or “savages”), developed shared goals, and their major contribution was to separate color from its traditional descriptive and representational realistic purpose, to make it an independent tool and visual element, driven on the canvas by primal feeling. Another of Fauvism’s artistic priorities was also independence from drawing in the overall balance of composition in pictorial space. The structure within the painting was given by simplified forms and saturated colors not necessarily true to the natural world nor to Renaissance perspective.

In its use and consideration of color, Fauvism brought together several early 20th-century French painters who were asserting their personal expression and individual instinct beyond academic theory, inspired by the experiments of the Post-Impressionists Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh and Georges Seurat. Of Cézanne, regarded as the father of all twentieth-century avant-gardes, they used the way of breaking down images into relatively homogeneous planes of color, but with imprecise contours; the boundaries of each color field did not always coincide with the contours of the objects represented, so that the image suggested by the color construction could contradict the realistic one. Of the legacy of postimpressionism, and in particular of the current of Neo-Impressionists such as Seurat, whose theory of color applied with the technique of pointillisme, “puntillism” or “pointillism” was known through the mediation of Paul Signac, there is strong trace in the taste for pure colors and juxtapositions, and of Gauguin and Van Gogh in the free expressiveness, which the Fauves amplified. The artist’s direct experience with his subjects, his emotional response to nature and surrounding reality, and individual intuition were employed in the service of representation: a tree could be red, the skies yellow, and a human face have intense green or blue patches. Representation thus gained an identity independent of the appearance of the things offered to the eye.

Some of the Fauves, such as Henri Matisse (Le Cateau-Cambrésis, 1869 - Nice, 1954), Henri Manguin (Paris, 1874 - Saint-Tropez, 1949) and Albert Marquet (Bordeaux, 1875 - Paris, 1947) had been students at the School of Fine Arts in Paris of the Symbolist artist Gustave Moreau (Paris, 1826 -1898) who professed precisely personal expression as a necessary attribute of a great painter. Others, such as André Derain (Chatou, 1880 - 1954, Garches) and Maurice de Vlaminck (Paris, 1876 - Rueil-la-Gadelière, 1958) who worked together in a studio in Chatou, flowed into the Fauves as fervent admirers of expressive violence à-la Van Gogh, along with a small core who had settled in the port village of Le Havre, Raoul Dufy (Le Havre, 1877 - 1953, Forcalquier), Othon Friesz (Le Havre, 1879 - Paris, 1949) and Georges Braque (Argenteuil, 1882 - Paris, 1963) followed Matisse, the eldest among them and with an autonomous personality, considered the “head of the school” and their highest representative.By 1908, the members of the group had gone their separate ways to research in other directions, however their fundamental ideas and works, which redefined pure color and form as a means of communicating the artist’s emotional state, influenced art for decades to come, foreshadowing the poetics of Cubism and Expressionism.

The name and history of the Fauves

Some of the artists who flowed into the movement were already painting works later considered to be Fauves before the exhibition occasions that in 1905 and 1906 determined their notoriety and triggered scandalized reactions from the public and critics. The name “Fauves” in fact, which translated stands for “beasts” or “savages,” was sarcastically assigned to them by art critic Louis Vauxcelles (Paris, 1870 - 1943) following an initial exhibition of works by Matisse and others at the Salon d’Automne in 1905. The Salon had been founded just two years earlier, in 1903, precisely to allow modern artists to exhibit freely, as the conservatism of the academic environment appeared insensitive to novelty and critical. The painter Matisse recalled the 1905 episode in these words, “Derain, Manguin, Marquet, Puy and others had placed their works near each other in one of the galleries: a sculptor was displaying an Italian-style child bust in the center of the same gallery. When Vauxcelles entered he exclaimed, ’Heck, Donatello among the beasts!’”

Striking was the violence in the use of unnatural color, disruptive of the academic style and that of the Impressionists who, only a few years earlier, declared a desire for “the painting to reflect the visual impression” of reality. Those young painters were inspired by postimpressionism.

But the formation of Fauvism, which, as noted above, was not a current with an a priori defined program, must be traced back to and was due to the period between 1894 and 1897, when Matisse, Manguin, Marquet along with others such as Charles Camoin (Marseille, 1879 - Paris, 1965) and Georges Rouault (Paris 1871 - 1958) met in the atelier of painter Gustave Moreau at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, School of Fine Arts in Paris: the master’s watercolors in freely arranged patches of color and the line of his oil sketches constituted an early contribution to the pictorial training of the future Fauves, whom Moreau himself stimulated to free research, autonomous from academic conventions.

Between 1897 and 1898 came to Paris, in addition to Othon Friesz, the Dutchman Kees van Dongen (Delfshaven, 1877 - Monte Carlo, 1968) and Jean Puy (Roanne, 1876 - Roanne, 1960), who came into contact with Matisse and Derain: the latter, in 1900, met De Vlaminck and rented a studio with him in Chatou, along the Seine, also one of the Impressionists’ favorite places. The two have often been lumped together under the term "Chatou School." Matisse as the older and more established artist, frequented, supported and encouraged them until that summer of 1905 when with Derain they spent a prolific and revolutionary period in Collioure, a port in the South of France, perfecting styles and techniques and working on numerous significant paintings (see Matisse’s Portrait of André Derain and Derain’s own Portrait of Henri Matisse).

At that special personal and artistic juncture, Dufy and Braque, better known as one of the founding members of the Cubist movement but who began as a member of the Fauves, who, having met Friesz, formed the so-called "Le Havre Group", influenced by Matisse’s painting, had also arrived in Paris. By the beginning of the century, the artists referred to as the Fauves were already in contact with each other, all agreeing in seeking a new mode of expression: the relationship with visible reality was no longer mimetic and nature was understood, in symbolist terms, as a repertoire from which to draw for free interpretation through the emotional values of sharp colors.

Matisse himself had come to the Fauves style after experimenting with various approaches of rejection to the traditional representation of space(Luxury, Calm and Voluptuousness of 1904 clearly demonstrates the influence of Seurat’s Neo-Impressionism), and although he never explicitly practiced pointillism, his observations of this technique led him to develop his own concept of color structure and pictorial space. It was in 1905 that Matisse visited Chatou’s studio, where he was powerfully impressed by the pure colors of the two painters Derain and de Vlaminck, and several of their paintings from that year would later flow into the annual Salon d’Automne at the Grand Palais in Paris, where they were distinguished by vividly colored canvases with spontaneous, full-bodied brushstrokes (Matisse participated with his famous Woman with Hat).

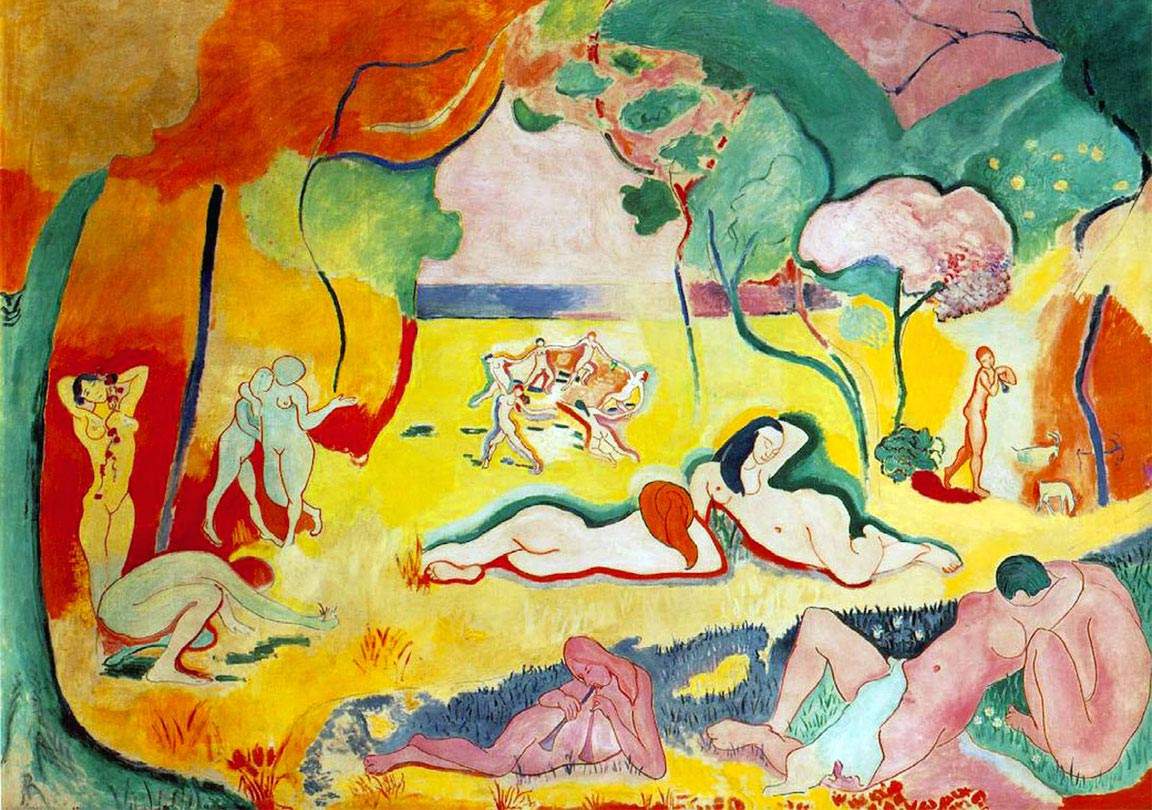

The success of Fauvisme was almost immediate, unlike Impressionism, for example, and generated contacts with gallery owners, dealers and collectors, and even the French government bought Fauves works from the very first Salons. An undoubted sign of the new relationship between art and the market that was being established at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries and that has characterized artistic production ever since. The year of full manifestation of the movement was 1906, which marked a further intensification of chromaticism, Fauvisme triumphed at the Salon des Indépendants, Matisse exhibited The Joy of Living there, and from that experience his modes of expression would also inspire other painters such as the Russian Vasily Kandinsky. Year, 1906, in which at the same time in Dresden were exhibited works by the German group “Die BrÏ‹cke,” which gave rise to German Expressionism from which the Fauves differed by less existential anguish, less polemical and critical intent toward society and, at the same time, a greater interest precisely in color.

Their art was shown in other exhibitions, most notably at the 1907 Salon des Indépendants, where the main attraction was a large room dubbed “The Lair of the Fauves.” But at the same time the relatively unified character of Fauvism faded, and by 1908 many of the painters were already working other in different artistic directions. It would be the disruption of Cubism (Picasso’s Les demoìselles d’Avignon is from 1907) that would break the ranks of the movement. Despite their brief existence as a united group, an aesthetic program rich in repercussions had developed in just four or five years. Color, by departing from the appearance of things, ended up altering the space of painting, between foreground and background, into an indefiniteness between the geometric limits of painted architecture. The dissociation of drawing from color opened the door to the Cubist revolution. Matisse’s Notes d’un peintre, “Notes of a Painter,” published in 1908 served as a formal record of many of the goals and ideas shared by the Fauves.

The style of the major Fauves exponents

The Fauves were all, though differentially, focused on color as a means of personal expression and a tool for constructing pictorial images, where compositional elements corresponded to the placement of the various colors chosen, rather than corresponding to a system of perspective or drawing. The chiaroscuro that created the effect of depth was abolished, in favor of a pasty blob drafting, affixed directly from the tube onto the canvas, useful for creating and scanning the proportions in the painting, in the name of an internal order of the composition that reflected emotional suggestions. In their shared preoccupation with expression through color and form, these artists were generally less interested in the novelty of their subjects: portraits, landscapes, seascapes, and figures in unspecified interiors.

When the Fauves appeared on the Paris art scene, the most revolutionary idea of landscape up to that time corresponded to that developed by the Impressionists: open air, clear palette and immediate reflection on canvas of direct visual impression. All this had already been challenged by artists such as Gauguin and Van Gogh who, in the diversity of their inspiration, had painted intensely subjective landscapes with a strong symbolic charge. While the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists had depicted scenes of out-of-town and then modern urban life, such as the boulevards, cafes, and environments of Paris and its environs, for the Fauves the visual impact of color composition took primacy over any possible narrative or symbolism.

The painting of the Fauves was intensely vital and all but distress-free. Beginning with the leader of the school Matisse, who gradually moved away from the use of subtle shades of mixed colors and in his “wild” period worked with brilliant and disruptive flat colors. “The expressive component of color,” he asserted in the wake of Moreau’s teachings, had to “emerge purely instinctively,” and the choice was given by “observation, emotion, sensitive experience.”

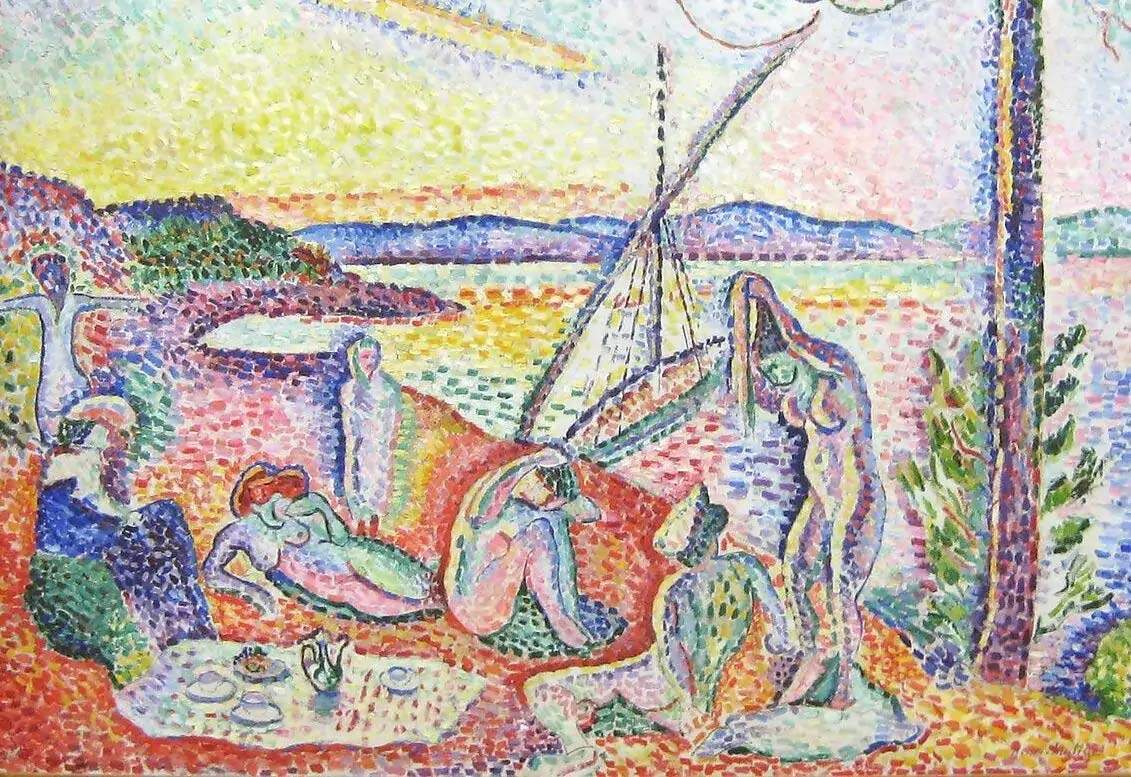

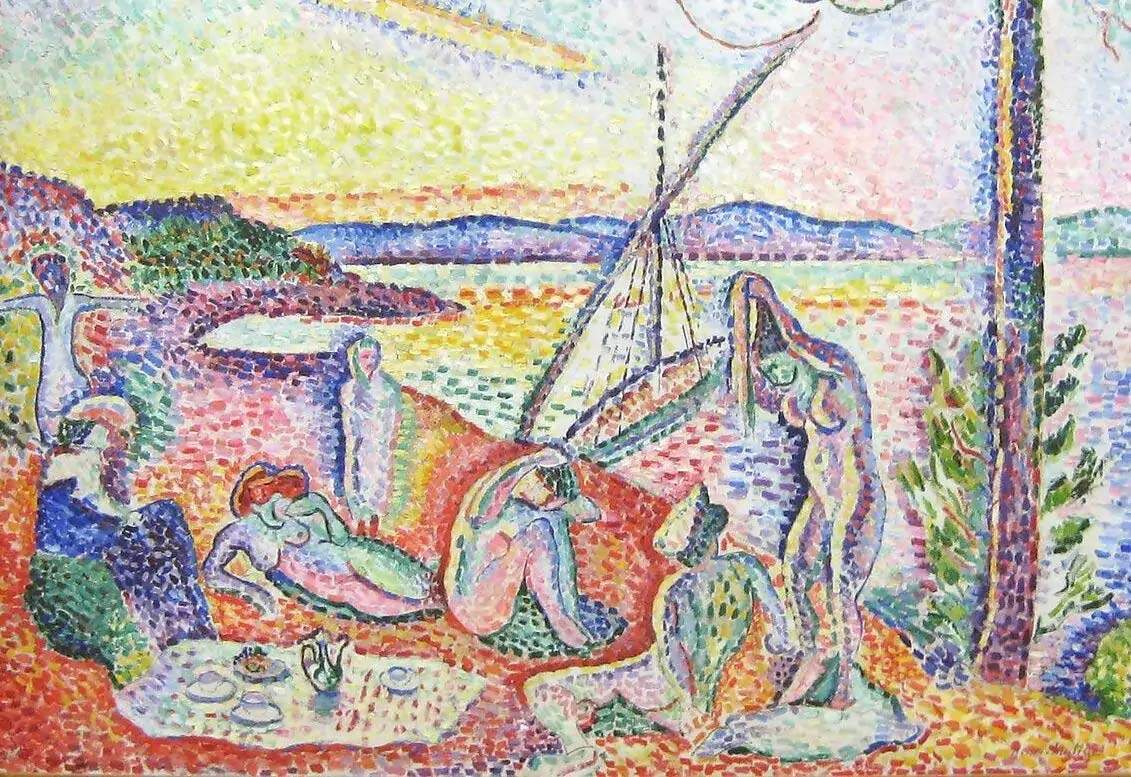

In the 1904 work Luxury, Calm and Voluptuousness, clearly influenced by Seurat’s pointillism in the use of small touches of color, but with which Matisse revisited this technique, there is a strong contrast between the expressive violence and the idyllic serenity of the painted subject. Taken from Charles Baudelaire’s poem Invitation to a Journey, it is a harmonious ideal country where precisely “everything is order and beauty, luxury, calm and voluptuousness” and where oranges, yellows, greens and other colors all retain their discrete places on the picture plane, never blending completely as in pointillism. Thus in The Joy of Living of 1906, perhaps Matisse’s best-known Fauvist work of strong visual contrasts that seem to vibrate, his nudes are in sensual bliss, connected to each other and to the landscape by a sinuous network of curving lines and bright, unnatural colors. A capital work of the twentieth century this one, like Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), because of the artist’s expressive reinterpretation of the human figure and precisely the landscape.

In the same years of Matisse’s early experiments with postimpressionist techniques, the two painters Derain and de Vlaminck did the same, who then developed their own common interest in bold colors and a particular brushstroke. Derain’s Fauvist paintings translate every tone of a landscape through vigorous long and short brushstrokes, compared to the agitated intense swirls instead of de Vlaminck.

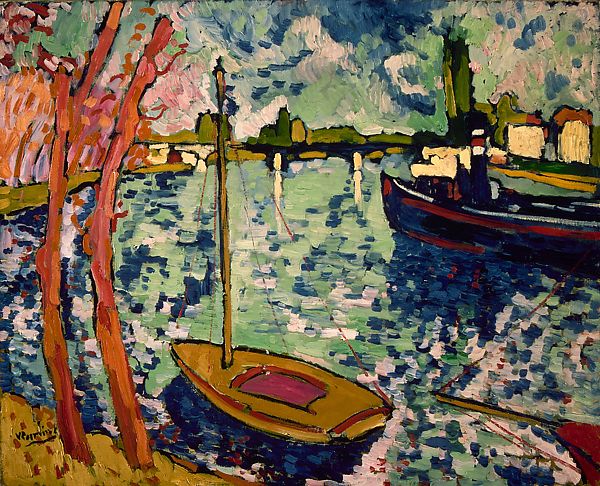

Derain, like Matisse, was known for his use of pure hues and simplified forms and interpreted landscape by departing from earlier depictions. In the famous Mountains at Collioure (1905) he used isolated brushstrokes, influenced by Divisionist painting, to texture the trees and terrain of his landscape, and in the view in The Docks of London for example, a 1906 canvas, the almost banal subject of barges, smokestacks and sailors was revolutionized by the untrue coloring, of the greenish water and sky, and by a bold framing from above. To the richness of color, Derain combined a remarkable sense of measure and a thoughtful vision of natural reality, unlike the passionate and impulsive de Vlaminck, who more than any of his contemporaries felt the influence of Van Gogh’s immediate and intense technique. For The Seine at Chatou, also from 1906, Vlaminck used impasto, a mode practiced by many Fauves, with thick patches of paint then brushed together in short strokes to create the effect of movement, using for the water and sky a range of blues and greens as well as dazzling white highlights and contrasting reds and oranges, for a final effect of vibrant luminosity and movement, in which traditional detail and perspective give way to a sense of lively delight.

Circus, a suburban landscape still from 1906, features charged brushstrokes and strident colors, which follow the directions of the objects depicted creating like a wave, affirming an uncontrolled expression of vitality, which, he himself wrote, came to him “from the heart and guts without concern for style. ”This tendency to distort forms with colors to express inner feelings had a decisive influence on the Expressionists.

|

| Fauvism, the color revolution. History and style of the Fauves |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.