Expressionism. Origins, development and main exponents of the movement

Expressionism is one of the major artistic currents of the early 20th century and had Germany as its center of irradiation in the years leading up to World War I, to materialize in different orientations and groups of artists, including Austrian, French, and Russian artists, who shared a free and subjective use of the artistic medium. As early as the last decade of the nineteenth century, personalities such as the Frenchman Paul Gauguin, the Dutchman Vincentvan Gogh, the Belgian James Ensor, and the Norwegian Edvard Munch had transformed academic and Impressionist principles in an expressionistic sense, revolutionizing the canonical composition of the painting and employing color, no longer only as a function of rendering luminous and atmospheric phenomena, but as a privileged tool for expressing an intense personal emotional charge.

The Expressionist current emerged around 1905-1911, at the same time as French Fauvism and Analytic Cubism , led by groups of artists such as Die Brücke (“The Bridge”) and Der Blaue Reiter (“The Blue Rider”) in the atmosphere of unease and turmoil that preceded the war. The epicenters of the movement were a number of German cities such as Dresden, Munich and Berlin, later to spread throughout Europe. The German expressionists of the Die Brücke group, led by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (Aschaffenburg, 1880 - Davos, 1938), Fritz Bleyl (Zwickau, 1880 - Bad Iburg, 1966), Erich Heckel (Döbeln, 1883 - Radolfzell am Bodensee, 1970) and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (Rottluff, 1884 - Berlin, 1976), employed intense use of color and line in urban scenes and often grotesque portraits, showing feelings of alienation from the modern world. While Futurism in Italy during the same years looked confidently at the technical achievements of Western civilization, the German Expressionists turned primarily to interiority, anxieties and hopes regarding the society of their time.

Expressionism demonstrated the need to investigate the inner, dark side of human consciousness and expressiveness and to recover seemingly lost feelings of authenticity and spirituality. Indeed, it would establish itself with the members of Der Blaue Reiter, Vasily Kandinsky (Moscow, 1866 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1944), Franz Marc (Munich, 1880 - Verdun, 1916), Gabriele Münter (Berlin, 1877 - Murnau am Staffelsee, 1962) and others, a more mysterious and spiritual quest that sought to communicate the immaterial life of man, anti-naturalistic and anti-figurative that would lead all the way toAbstractionism.

Origins and development of expressionist groups in Europe

The roots of the German Expressionist school lie in the works of Gauguin, Van Gogh, Ensor and Munch, each of whom in the period between 1885 and 1900 developed a very personal style of painting. These artists had used expressive possibilities to explore dramatic and emotional themes or simply to celebrate nature with hallucinatory intensity, and detached from the literal representation of reality, they had entrusted painting with the most subjective visions and moods.

The main wave of Expressionism came in 1905, when a group of German students led by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner formed a loose association called Die Brücke (“The Bridge”) in the city of Dresden. The group included Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, bohemian artists in revolt against academic tradition who wanted to infuse German art with a new stylistic vigor through highly liberating and spontaneous but organized and shared expression. The first members of Die Brücke were soon joined by the Germans Max Pechstein (Zwickau, 1881 - Berlin, 1955) and Otto Müller (Liebau, 1874 - Breslau, 1930) and the Dane Emil Nolde (Emil Hansen; Nolde, 1867 - Seebüll, 1956). Influenced by their postimpressionist predecessors, they were also interested in African wood carvings and the works of medieval and Renaissance artists such as Albrecht Dürer or Matthias Grünewald. In fact, their painting style matured in years when cultural references were being transformed: the whole of Europe rediscovered “primitives,” the arts of distant peoples-Africa, Oceania, North America, the Far East-which supplanted Eurocentric classicism. What these young artists, polemical of contemporary society, wanted was to build a “bridge” between past and present that united “all the revolutionary and stirring elements.” Their name comes from a quote from Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-85) by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who stated, “What is great about man is that he is a bridge and not an end.”

1906 was the year when, while Fauvisme triumphed in Paris at the Salon des Indépendants (Matisse exhibited The Joy of Living there), showing a shared interest in the intense and passionate use of color, at the same time works by the Die Br?cke group were brought together and exhibited for the first time in Dresden in Karl-Max Seifert’s chandelier factory. Occasionally, the ideological premises of the movement were made clear in the leaflet-manifesto created by Kirchner using the woodcut technique, which accompanied the exhibition and summarized their break in favor of a freer, youth-oriented aesthetic. “With faith in evolution, in a new generation of creators and connoisseurs,” the manifesto stated, “we call all young people together. And as young people, embodying the future, we want to liberate our lives and limbs from the oldest and most established powers. Whoever renders his creative impulse directly and sincerely is one of us.” Although without a binding program, Die Brücke thus intended to be a union of forces that fought against the stagnation of art in the name of the creative freedom of the artist.

Compared to the Fauves, the Germans differed in their greater existential angst and critical spirit toward society. The Dresden artists used distorted forms and jarring, unnatural colors, following an aesthetic of medieval German art from which they retrieved graphic techniques, precisely, such as woodcuts. Their key stylistic element was the abandonment of the search for three-dimensionality, false space and false volume as opposed to thedirect emotional experience aroused by the world. From 1907 to 1911, the group spent much of its time in Dresden, organizing exhibitions and using Kirchner’s studio as a hangout, until it disbanded in 1913 due to artistic differences that arose among the members and especially as a result of some of them moving to Berlin in 1911. Die Brücke within a very few years had become popular among young artists, so much so that it inspired other avant-garde groups and movements. Just in 1911 in the meantime in Munich the group Der Blaue Reiter (“The Blue Rider”) was formed from a split of some members of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (New Artists’ Association). The triggering event was the rejection from an exhibition of the painting The Last Judgment (1910) by one of them, Vasily Kandinsky.

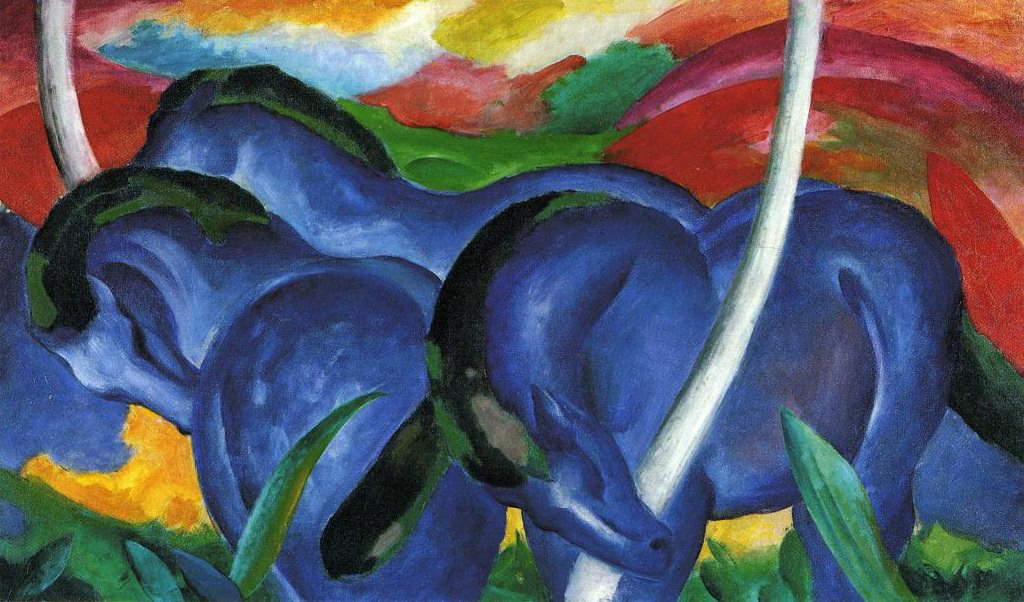

Besides the Russian Kandinsky, whose driving personality was oriented toward the search for pure rhythms of forms and colors as expressions of states of mind, the group included, the Germans Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, August Macke (Meschede, 1887 - Perthes-lès-Hurlus, 1914), the Russians Alexej von Jawlensky (Torok, 1864 - Wiesbaden, 1941) and Marianne von Werefkin (Tula, 1860 - Ascona, 1938), and among others the Swiss Paul Klee (Münchenbuchsee, 1879 - Muralto, 1940). This internationalism led the group to organize several traveling exhibitions, making them an indispensable force in promoting early avant-garde painting. The group shared an inclination toward abstraction, symbolic content and spiritual allusion, seeking to express emotional aspects, through brightly colored structured representations. Their name was derived from a 1903 work by Kandinsky featuring a rider on horseback and The Blue Horses painted by Marc in 1911, a recurring motif in their work that symbolized the transition from tangible reality to the spiritual realm and thus served as a metaphor for artistic practice. For the other members, too, this idea of pictorial art became central to moving beyond realistic representation and deepening abstraction. Although Der Blaue Re iter did not have a true manifesto, the group’s artists produced an Almanac, Der Blaue Reiter Almanach, which was published in early 1912 and included more than 140 works of art, including works by Van Gogh, Cézanne and Gauguin, with 14 articles and theoretical essays. The group was united in aesthetic innovations, influenced, for them as well as for the Die Brücke artists, by medieval and primitivist art forms, Fauvism and Cubism at the time. However, with the outbreak of World War I in 1914 Marc and Macke were drafted into German military service and killed shortly thereafter, and the Russian members of the group, Kandinsky among others, were all forced to repatriate. Der Blaue Reiter disbanded soon after.

The elasticity of the current of Expressionism meant that many artists beyond Germany’s borders were identified as Expressionists, even considering that German groups never referred to themselves as such and that, in the early years of the century, the term was widely used for a variety of styles. Austrian artists such as Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele were inspired by German Expressionism, although independent of an organized group. Both sought to express the decadence of modern Austria through equally expressive depictions of the human body, with sinuous lines, charged colors and distorted figures, each interpreting the stylistic current individually. Such as in France, Georges Rouault, known for his expression with intense colors and heavy layers of paint, Russian-French Marc Chagall who exhibited in Berlin in 1914 creating an impact on the German expressionists, Chaim Soutine, a Russian in Paris, who was one of the main supporters of the development of Parisian expressionism.

After World War I, however, Expressionism began to lose momentum and fragment, although stylistic outcomes persisted even in the interwar period, particularly in Germany, where the political and social crisis became more acute. When Hitler seized power in 1933, his victims, along with so many millions of men, were also the expressionist painters, German and foreign, for their charge of rebellion against bourgeois laws restrictive of the artist’s autonomy. Their art was considered "degenerate,“ they themselves treated as ”degenerates," their works withdrawn from museums and collections. Meanwhile, the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) current was emerging, which developed as a direct response to the strongly emotional principles of Expressionism. But the trend baptized by the Germans at the turn of the century, linked to the spontaneous, instinctive and highly emotional qualities of each artist, would return much later in the 20th century with Abstract Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism.

The style of the major exponents of expressionism

Two sides of German Expressionism should be considered. The Die Brücke group, operating first in Dresden and then in Berlin was one of the first influences for the Munich Der Blaue Reiter artists, although, nevertheless, representatives of the two groups pursued quite different goals. Acknowledging the importance of the bold color introduced by the French Fauves, the Die Brücke artists used intense and pronounced colors to enhance the expressiveness of their simplified figures. But for Kandinsky and his people, those same colors had to transcend representation and resonate higher in the human soul. And although Der Blaue Reiter was also born out of the same alienation from the modern world that had moved Die Brücke so deeply, the response was not to confront that feeling through disturbing representations of a traumatic experience, but to attempt to transcend it through abstract artistic means. Both groups had found inspiration in primitive art forms, but the one introduced a certain level of raw and anguished expressiveness, the other supplanted it with more harmonious compositions of colors and non-objective forms.

The Die Brücke made use of a whole range of stylistic resources from the very beginning: two-dimensionality, the use of violent colors and outlines, the “gestural” immediacy of sign and brushstroke; they developed in sum early on a style recognizable for its harshness, boldness and visual intensity. The works present street scenes, natural landscapes and portraits of contemporary subjects in charged and unstable atmospheres. Provocative images of modern society with prostitute models and other characters, city dwellers alienated from the experience of urban life.

Among the prominent works of the Die Brücke current, those by the leader Kirchner encompass all of these motifs: from Marzella (1910) in which the artist portrays a solitary young naked body, depicted without hedonistic complacency and constrained in a marked dramatic outline, to Berlin Street Scene (1913), in which two prostitutes with mask-like faces dominate the center of the street between indistinguishable men. The first work with broad strokes of color juxtaposed with the synthesized forms of the body, where reality is present and recognizable, not, however, in its appearance, but read by the artist, penetrated beyond what the common eye sees: the depiction of a teenage model already aware of the tragedy of the world. The second, part of a series of Berlin street scenes, in which contours and forms almost blur, emphasizing the city’s intermingling of people and commodities in a Berlin in which, having become a metropolis, one could buy anything, including the availability of those prostitutes, amidst an ever-growing and increasingly anonymous city crowd.

Widespread many of the works of the Die Brücke exponents expressed restlessness, and in general a kind of frenetic intensity of feeling in response to the possibilities and contradictions of modernity. The formal qualities of their art were undoubtedly conditioned by city living, but also by their frequent extra-urban travels among the lakes and forests of Germany. They painted numerous nudes, embracing naturism, the philosophy of social nudity introduced by German intellectual circles in the late 19th century, as part of their radical rejection of bourgeois social norms. Scabrous bodies in domestic city interiors and in nature. One of their most original contributions was the reintroduction of woodcuts, which allowed a violence to their deliberately rebellious language. Through the stark juxtaposition of whites and blacks in compact and simplified forms, it was one of the most effective and widely used means of expression, an excellent example of which among others is found in Otto Müller’s Bathers of 1912.

In contrast, the works of Der Blaue Reiter constituted the abstract counterpart to the distorted figurative style of Die Brücke. As much as they had a focus on primitivism and the practice of woodcuts (Franz Marc, The Yellow Cow, 1911; Cover of Der Blaue Reiter Almanach, 1911-1912), the innovation of their painting was in the idea that colors and forms led to a contact with spiritual values. This is already understood from the adjective “blue,” which referred to Kandinsky and Marc’s belief that blue with its hues was the color that most symbolizes the ability to go beyond the earthly condition.

They employed colors that were not naturalistic, as for Die Brücke, but with decidedly more lyrical and evocative effects, each interpreting the forms with his or her own gaze, as a subjective rebellion against reality. A first total example is in Kandinsky’s work, the 1909 Church in Murnau, which would seem to express a dominant feeling of mystery and silence, alluding to the Murnau church in Bavaria but not really describing its details. When in 1910 Kandinsky wrote the treatise The Spiritual in Art, published in late 1911 and translated from the German original into French and English, he solidified himself as a revolutionary theorist of art. For Kandinsky, the modern artist was on a mission to lead his or her viewer to spiritual transcendence through his or her abstract, or non-objective expression, built on knowledge of the work’s effect not only on the eye but on the soul, a principle he called “inner necessity.” Kandinsky’s most decisive suggestion was to unravel the connections between visual components and extra-visual elements lacking tangible or figurative manifestation, such as emotion, thought, abstracts par excellence.

In their search for a language to express their abstract approach, the artists in the group led by Kandinsky drew parallels between painting and music, often titling their works “compositions,” “improvisations,” and “studies,” drawn from musical terminology, exploring synesthesia, as an association between the senses in the perception of color, sound and other stimuli. Made during his experience with Der Blaue Reiter, the work Composition VII (1913) is widely considered one of Kandinsky’s greatest masterpieces. It is his largest oil-on-canvas painting, measuring two meters by three meters, presenting an array of colors and shapes that do not compose immediately recognizable but deeply evocative images. The painter defined his pictorial abstractions as “inner visions” similar in form and structure to a symphony.

Among others, the artist Paul Klee, an experimental musician and draftsman, also initiated a revolutionary coloristic exploration in his period in Der Blaue Reiter. Inspired by Kandinsky’s writings, he went beyond his early black-and-white works and devoted himself to an intense study of color and abstraction(In the Style of Kairouan, 1914) that made him a central member of the group. While some artists after these experiences rejected Expressionism, others would go on to expand its stylistic innovations.

|

| Expressionism. Origins, development and main exponents of the movement |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.