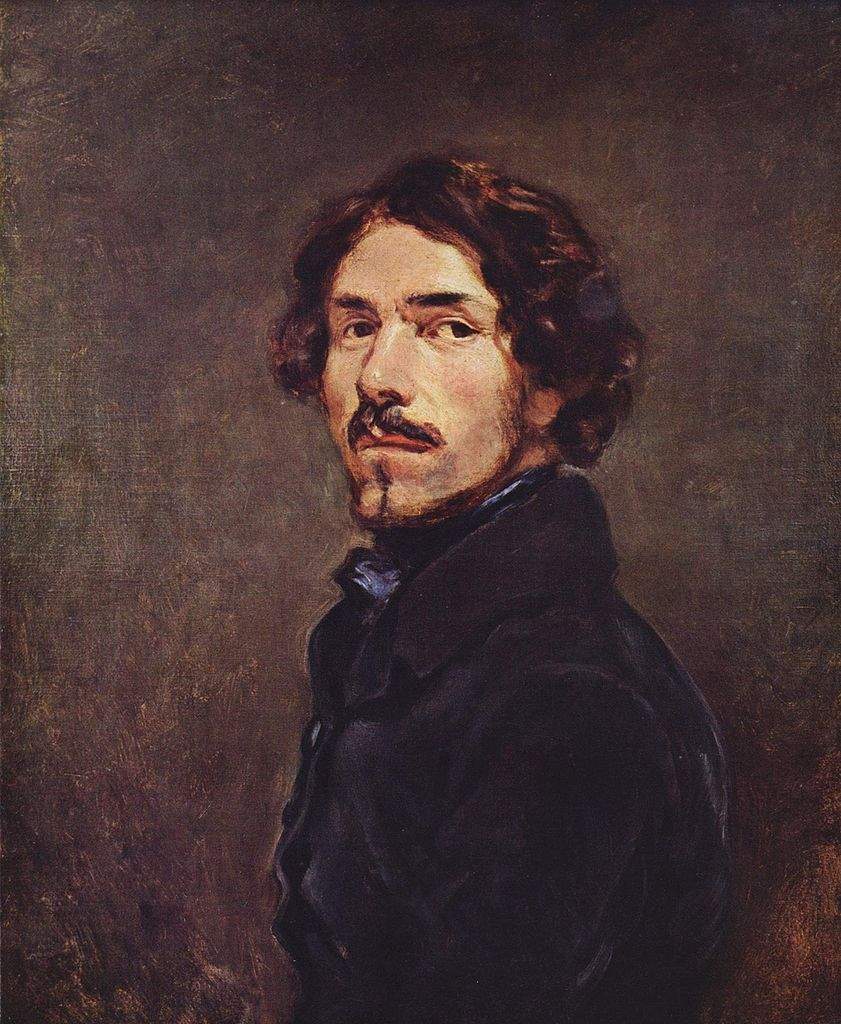

Eugène Delacroix (Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix; Charenton-Saint-Maurice, 1798 - Paris, 1863) was a celebrated French painter, a leading exponent of Romanticism in France. Delacroix’s works are characterized by dynamic and richly colored brushstrokes, whose outlines are deliberately ill-defined, and scenes with solemn and epic tones, setting himself in contrast to the neoclassicist tendency of the artists of his contemporaries. His style was instrumental for the Impressionists.

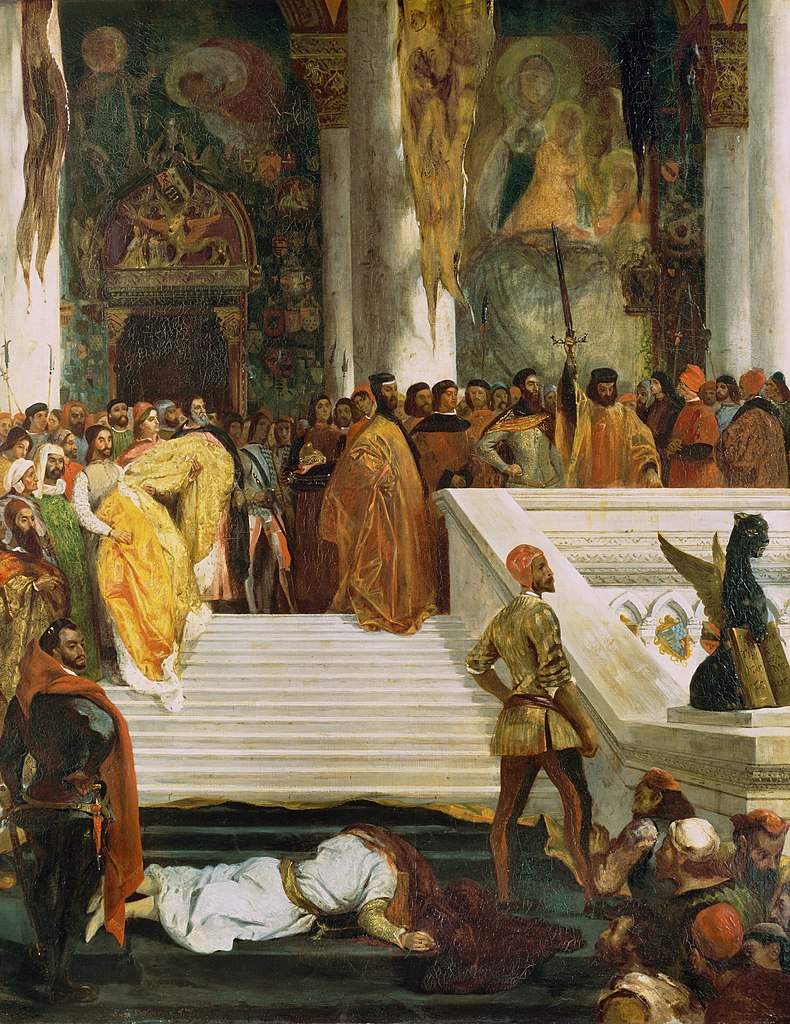

An important part of his artistic output is characterized by a personal interest in exotic settings, culminating in a trip to Algiers. He illustrated several literary works by Shakespeare, Goethe, and Scott. But he is best known for his large-scale historical-themed paintings, such as Liberty Leading the People. He was also one of the first artists to take an interest in contemporary history.

Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix was born into a wealthy upper middle-class family on April 26, 1798, in Charenton-Saint-Maurice. His father, Charles Delacroix, was a political figure, foreign minister under the Directory and later prefect in Marseille and Bordeaux. His mother, Victoire Oben, was the daughter of Louis XVI’s cabinetmaker. She lost her father when she was only eight years old, and soon afterward the family moved to Paris. Here Delacroix attended the imperial lycée, following a humanistic education, and immediately showed a flair for drawing. Thus, once he had completed his studies, Delacroix in 1815 entered the workshop of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, a neoclassicist artist and emulator of David. In the workshop, he was able to assimilate the basics of painting technique and became friends with another pupil who would become very famous, Théodore Géricault. Their bond was solid over the years. Soon, however, Delacroix turned away from his master’s precepts and continued as a self-taught painter, passionately studying the masterpieces of the great Italian masters preserved in the Louvre, such as Michelangelo Buonarroti, Titian Vecellio, Raphael, and especially Rubens, whose opulent style he admired. He obtained his first prestigious commission in 1819, for the church of Orcemont, where he painted a Virgin of the Masses in which the study and influence of Raphael Sanzio is evident.

Inspired by his acquaintance with Géricault and the large canvases he used to paint, Delacroix also began to try his hand at paintings of the same type, the first of which was Dante’s Boat, which he made in 1822 at the age of twenty-four. In the same year he was admitted to the Paris Salon, where he exhibited precisely Dante’s Boat, provoking wide discussion and objections. The large canvas was, in any case, purchased by the French state and moved to the royal Luxembourg Palace in Paris, then the seat of the Chamber of Peers. The artist was not at all swayed by the objections aroused at the Salon and reappeared there two years later with another monumental work, The Massacre of Scio (1824). The criticism this time was even harsher than that reserved for The Boat of Dante, but Delacroix again remained unaffected. The French state also purchased this painting for the royal palace in Luxembourg. In the same year, Delacroix left for London with the intention of admiring the works of John Constable, which by his own admission “did him a great deal of good.” Indeed, the English naturalistic style was an important part of Delacroix’s artistic production.

In 1830 the artist painted Liberty Leading the People, his greatest masterpiece. Delacroix returned to the 1831 Salon with this major new canvas, and to reward and emphasize the importance of the subject matter, he was awarded the Legion of Honor. Two years later, Delacroix, who had long been fascinated by the Orient, especially following news of the wars for Hellenic independence, decided to follow Count de Momay on a diplomatic mission to Algiers on behalf of King Louis Philippe. The trip to Africa was of great inspiration for the artist’s later canvases, as he was greatly impressed by several Algerian elements during his stay, such as the dazzling equatorial light, the decorations of the houses, which would inspire him to explore novel color combinations, and finally the Algerian women. During his stay, he captured as many images as possible in seven notebooks that he filled with sketches and took back upon his return home as inspiration for new exotic canvases.

By the time he returned from his mission, Delacroix was the most sought-after artist among the fashionable French aristocracy, both for his works and for his personality. Indeed, he turned out to be very charming as witty and intelligent, and at the same time solitary, elusive, and mysterious. Among other things, he did not want to marry and had very few friends, whom he nevertheless considered authentic. As we have seen, some of Delacroix’s most famous paintings were the subject of major criticism, and even The Fury of Medea of 1838 was not exempt, punctually causing a great deal of uproar at the Salon. In any case, this painting, too, was purchased by the state for the Museé des Beaux-Arts in Lille (it would seem that Delacroix had preferred that the painting be exhibited at the Luxembourg along with Dante’s The Boat and The Massacre of Scio, so that all of his major production would be brought together in one place).

Delacroix, meanwhile, alternated very prolific periods, thanks to numerous commissions, with periods of severe illness. He suffered from laryngitis due to prolonged exposure to the cold, and the efforts he had to make large wall decorations for several palaces in Europe undermined his health. He decided, then, to buy a cottage in the Champrosay countryside, where he settled in search of refreshment for his debilitated physique. Even in the countryside he continued to paint very prolifically. He finally moved to Paris in 1857, where he later died on August 13, 1863. His remains lie in the Père-Lachaise cemetery.

Eugène Delacroix is recognized as the leading French exponent of Romanticism. Romanticism differs from the contemporary Neoclassical style (whose principal artist in France is Ingres) in its greater emphasis on color, movement, and reflections of light, rather than on precision and sharpness of drawing. What the Romantics were after, and Delacroix clearly was no different, was to transport strong, dramatic, even tragic feelings onto the canvas so that the viewer could feel them firsthand once he or she was in front of the work. To achieve the desired effect, Delacroix used a technique that consists of very rapid brush strokes of pure colors juxtaposed with their respective complementary colors, so as to bring luminosity to its fullest expression.

Delacroix’s painting is profoundly influenced by the great artists of the 16th century; he himself discusses this in some detail in passages of his Journal: “All the great artistic problems were solved in the 16th century. In Raphael, perfection of drawing, of grace, of composition. In Correggio, in Titian, in Paolo Veronese, of color, of chiaroscuro. Along comes Rubens, who has already forgotten the traditions of grace and simplicity. By dint of genius, he reconstructs an ideal. He draws it into his temperament. Strength, surprising effects, expression pushed to the utmost. Does Rembrandt find it in the indefiniteness of reverie and rendering?” In turn, Delacroix would become a point of reference for Impressionist painters, Paul Cézanne above all, in his use of color, and traces of his influence can also be seen in Van Gogh, Degas and Odilon Redon.

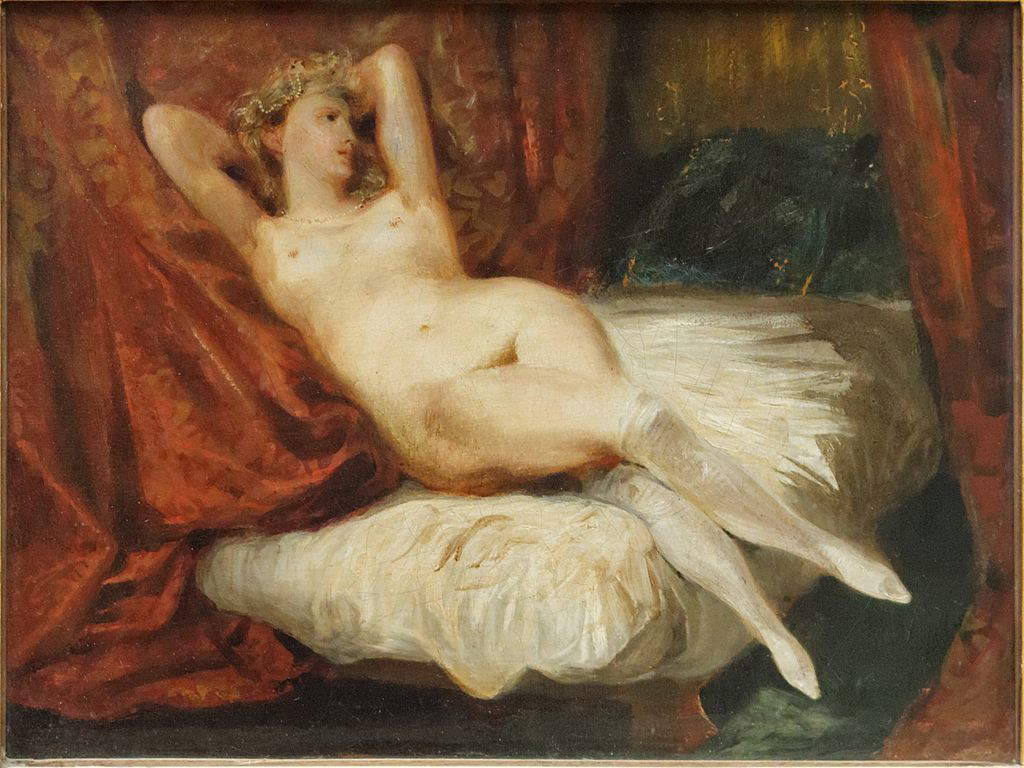

During his lifetime, Delacroix painted an enormous amount of works; in fact, it is said that he painted every day. After his death, at least 9,000 were found, divided between drawings and paintings. Within this gigantic output is a great variety in both themes and techniques. The artist ranged from mythology, historical events, military scenes, portraits, still lifes, landscapes done as wall decorations, and with reference to painting technique he produced large and smaller paintings on canvas, oil paintings, watercolor and pastel paintings, and frescoes. The most important works are large canvases depicting epic and historical themes and episodes. These are maximum masterpieces that marked crucial stages in art history, and at the time, precisely because of their uniqueness, caused divisive reactions. Indeed, detractors could not stomach the greater emphasis on the emotion of the episode being told than on the precision of the drawing, deeming the works confusing and exaggerated in sentiment.

The power of these works, however, lies precisely in theauthenticity of the emotion reproduced on the canvas. The Massacre of Scio, for example, reports an episode that had affected Delacroix personally, that is, he wished to reproduce on canvas the feelings that the news of the failure of a Greek revolt against the Ottoman Turkish Empire had aroused in him. The subject matter is oriental, highlighting Delacroix’s interest in those territories that he would later, as we have seen, physically reach in 1833.

As for his most famous work, Liberty Leading the People, here for the first time Delacroix decided to take political sides, something he had not done previously for other historically themed paintings. In this case, he decided to pay homage to the people’s revolt against the reactionary and censorship-prone policies perpetrated by Charles X, King of France who succeeded Louis XVIII. Although the canvas was purchased by the French state and exhibited in the throne room of the Luxembourg Palace, it was later hidden in an attic as it was still considered too “revolutionary.” Famous are the quotations and references that can be discerned by analyzing this work, from the Venus de Milo found in the features of the personified “Liberty,” to the pyramidal structure of the composition (at the center of which are the bright colors of the French flag that illuminate the dark tones of the rest of the painting) that is nothing but a quotation from Géricault’s Raft of Medusa. So too are the two men in the foreground (with the sock detail) exactly taken from his friend’s work. The substantial difference between the two paintings is found, at any rate, in the sentiment they express, optimistic and pugnacious that of Delacroix, while desperate and tragic is the work of Géricault. Freedom Leading the People is still often used as a symbol of the struggle for human rights and often appears as an iconographic image in support of other art forms (for example, it was used in 2008 as the album cover for the rock band Coldplay’s album entitled Viva la Vida or Death and all his friends).

The works Delacroix produced upon returning from his diplomatic mission to Algeria also received much acclaim. Indeed, he succeeded in authentically restoring the exotic charm of those places, sublimating the color combinations in a way that almost anticipates Impressionism, or rather from which Impressionist artists would learn much. Among these works, the most famous is The Women of Algiers in Their Apartments (1834), in which Delacroix depicts a harem, a place where women and children gathered in Muslim mansions. The viewer is welcomed among draperies, carpets, and colorful clothing, and made to enter an intimate place where they would not usually be able to enter. Delacroix succeeds precisely in capturing this nuance and restoring its emotional power to us.

One of Delacroix’s last known works before his death is Jacob’s Struggle with the Angel (1861) in which the biblical scene that gives the work its title is depicted through a voluptuous swirl of shapes and colors used precisely to emphasize the exertion of the fight. Beneath the religious episode there is also a more “romantic” meaning in the literary sense, namely the eternal struggle of the hero (the human Jacob) and the divine (the angel) that never ends. In fact, the two figures are portrayed precisely during a phase of the fight, crystallizing this struggle into eternity.

All of Delacroix’s major works are housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris, where they were transported in 1874, 11 years after the French artist’s death. They were brought together from Luxembourg and Lille, the city to which they were sent by the French state after being purchased at the Paris Salons. In Paris, it is also possible to visit the Musée Delacroix, which was carved out of the small house-workshop where the artist spent the last years of his life. Inside the Musée Delacroix are numerous drawings, paintings and memorabilia, as well as his autograph writings.

In France, works by Delacroix can be found at the Musée Fabre in Montpellier (one of those that holds the most), the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rouen, and those in Lyon, Béziers, Bordeaux, Nancy, and Nantes. It is also possible to find Delacroix altarpieces inside churches: for example, in Ajaccio Cathedral (the Triumph of Religion of 1821), in the church of Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis in Paris(Christ in Gethsemane of 1827), in that of Saint-Denys-du-Saint-Sacrement in Paris (the Pieta), and in that of Saint-Sulpice in Paris(Jacob’s Struggle with the Angel, theArchangel Michael and The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple of 1854-1861).

Outside France, there are important nuclei of Delacroix’s works at the Kunstmuseum in Basel, the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. In Italy, works by Delacroix are rare. However, the Uffizi Gallery holds a self-portrait of him, executed in 1840, and the Galleria Nazionale della Puglia in Bitonto holds a sketch for a Shipwreck Scene from 1833.

|

| Eugène Delacroix, the greatest of French Romanticism. Life, works, style |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.