Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, life and works of the German expressionist painter

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (Aschaffenburg, 1880 - Davos, 1938) was one of the active protagonists and animators of theGerman avant-garde. At the dawn of the 20th century, an international current destined to influence all modern art,Expressionism, was gaining ground, propelled by groups of daring young artists capable of breaking traditional patterns and completely renewing the conception of the visual work of art in the name of expressive freedom. Kirchner was among these daring artists: a painter, printmaker and sculptor, he was the leading personality and founder of the group of artists known as Die Brücke (“The Bridge”), which flourished in Dresden and then moved to Berlin in the years leading up to World War I.

Kirchner came from university studies, self-taught in drawing, when just before graduating with a degree in architecture he decided with fellow students Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff to found a group that would build a “bridge” between the academic tradition and the expressive interpretation of his own time, proclaiming visual art as an immediate and powerful expression of interiority. Embodying the bohemian spirit of the years at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the artists of Die Brücke, driven, in Kirchner’s words, to express themselves “directly and authentically,” blended “life and art in harmony.” A reaction shared with a broader German youth movement that challenged the lifestyle, alienating to the individual, given by the urbanization and conservatism of early 20th century German society.

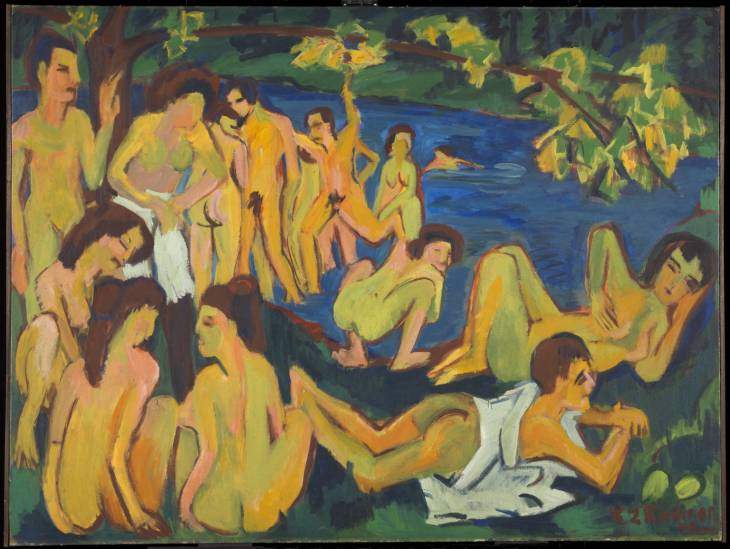

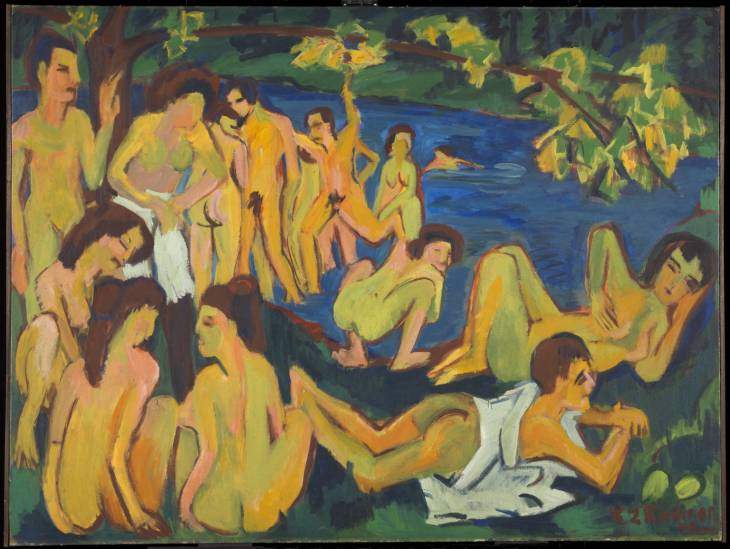

Kirchner before the psychological drama that the experience of war and Nazi censorship brought him, had in his best years ardently believed in an instinctive and natural way of living and working. In their joint studio, Die Brücke made life drawings of nude models in casual, informal poses, and during the summers they spent long periods together on lakes near Dresden, letting the works also evoke their freedom of costume, immersed in nature. In the years before he moved with the group from Dresden to Berlin, his output included in addition to studio nudes, portraits and scenes of urban life. In the Berlin years he continued with his distinctive metropolitan narrative, so much so that the paintings of that time, with figures and crowds in motion, marked a high point in his career. Contributing to the formation of his distinctive style, characterized by simplified flattened forms and intense, non-naturalistic colors, were both his contact with “primitive” African and Oceanic art, which penetrated Europe collected in ethnographic museums, and his knowledge of historical printing techniques, which, as with his colleagues in Die Brücke, he used recurrently and innovatively. Indeed, he produced, in addition to paintings and wood carvings, more than two thousand woodcuts and lithographs, with unique and unorthodox effects.

In the latter part of his life, he took refuge near Davos in Switzerland, painting rural landscapes, the mountains and inhabitants of that area, even experimenting with abstract painting, with the aim of participating as a German in “the international modern style” that was emerging. But the Nazis considered Kirchner’s art “anti-German,” and in 1937, as part of their campaign on“degenerate art” waged against the modern artworks they seized by the thousands from museums and private collections, they removed hundreds of his works. The following year he took his own life.

The Life of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was born on May 6, 1880, in Aschaffenburg, Bavaria, and began studying architecture in 1901 at the encouragement of his parents, cultivating his penchant for drawing primarily as a self-taught artist. While attending university classes in Dresden, he became close friends with Fritz Bleyl, who shared his radical view of art and nature. During this period, in 1905, Kirchner and Bleyl, along with fellow architecture students Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, founded the artists’ group Die Brücke (“The Bridge”). Their goal was to avoid traditional academic styles and create a new mode of artistic expression. Their name comes from a quote from Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-85) by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who stated, “What is great about man is that he is a bridge and not an end.” The painting of Die Brücke members was an immediate and powerful translation of inner conflicts, expressed through marked lines and vibrant, unnatural colors. The group would meet in a small room that served as Kirchner’s studio to practice figure drawing, and where they also shared amorous experiences with their circle of other artists and models. Much of the group’s output was inspired by the graphic work of the German medieval and Renaissance tradition and the bold palette of Post-Impressionist artists, and Kirchner with an interest in printmaking techniques and in particular the work of Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - Nuremberg, 1528), sought to revive and modernize his style in sculpture as well. The mission was to investigate the inner, dark side of human consciousness and expressiveness.

After the first exhibition in 1906 that Kirchner and the Die Brücke organized in Karl-Max Seifert’s lamp factory, numerous others followed from 1907 to 1911, before they moved to Berlin. Over 70 in their eight actual years as a group. To their time in Dresden, Kirchner and the others alternated long periods of summer retreat from the mundane, immersed in nature near the lakes of Moritzburg or on the Baltic island of Fehmarn. Their works presented provocative images of modern society, with charged and unstable atmospheres: street scenes and portraits of contemporary subjects, city dwellers alienated from the experience of urban life, as well as free figures cast in natural landscapes.

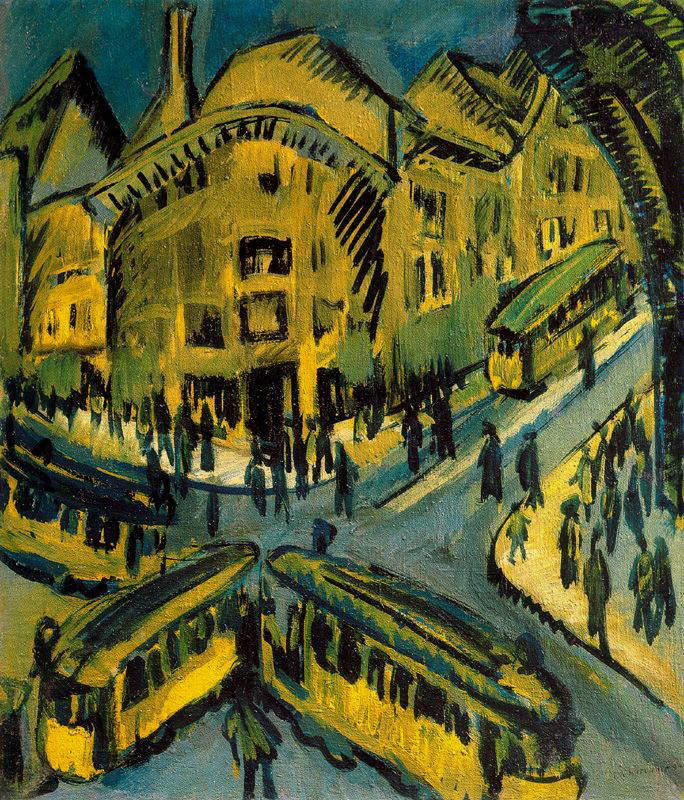

In 1911, Kirchner persuaded the rest of the Dresden painters to move to Berlin, where with Max Pechstein (who had joined Die Brücke in 1906) he wanted to found the private art school “Moderner Unterricht im Malen Institut” (Institute for Modern Teaching of Painting) that would promote their new modern artistic convictions. The group came into contact with the international avant-garde movements of French Cubism and Italian Futurism, and each artist responded differently to the new Berlin stimuli. Kirchner, for better or worse, was overwhelmed and unnerved by the city, which at that time was emerging as a cosmopolitan metropolis, and his work took on a more agitated and dynamic quality, capturing its frenetic pace, chaotic intersections and crowded sidewalks.

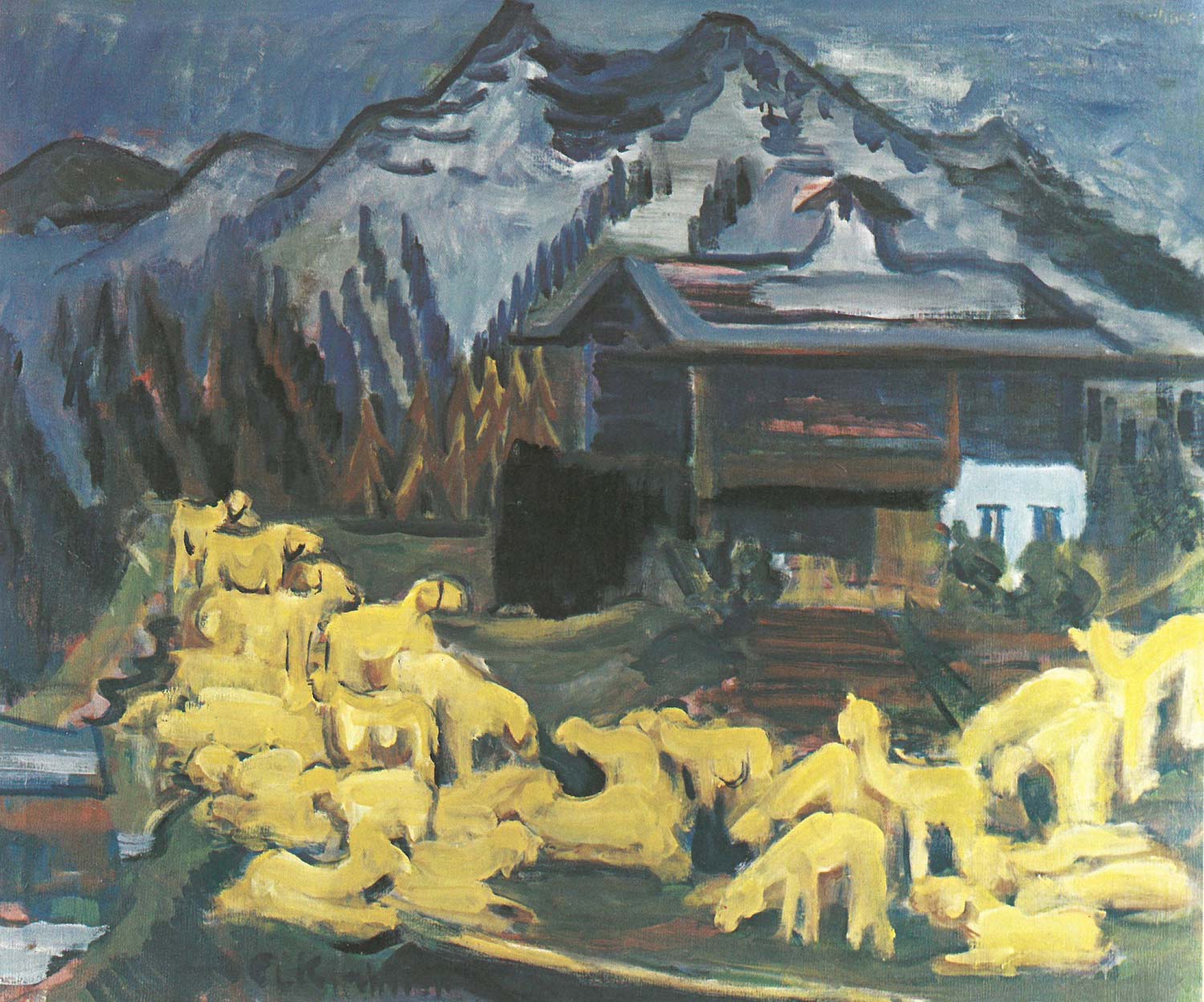

The years in Berlin marked a high point in his career: in 1913 after the formal dissolution of Die Brücke, he went on to determine his own identity as an artist with his first solo exhibitions in Germany at Museum Folkwang Hagen and Galerie Gurlitt in Berlin. He thus developed an interest in industrialization and the alienation experienced by individuals, gradually turning his attention away from the female nude between 1913 and 1915 to the streets of the capital, focusing on the disturbing city nightlife. While observing the changing political situation of World War I and its impact on German culture, Kirchner developed a style of bold and expressive brushwork, ringing colors, often distorted perspective, and swaying figures, in full rejection of convention. In 1915 he enlisted in the army, but was discharged shortly thereafter due to a nervous breakdown, the after-effects of which would haunt him for the rest of his life. He was hospitalized in several hospitals between 1916 and 1917, and still scarred by his military experience, in 1918 he moved to the village of Frauenkirch near Davos in Switzerland, and this new residence inspired a series of mountain landscapes markedly different from the more dramatic Berlin street paintings.

He continued to suffer moral and physical breakdowns, despite his growing success and reputation as a leading German expressionist, between exhibitions in Switzerland and Germany in the 1920s. In 1926 his first monograph and catalog of graphic works were published, in 1927 he received a commission from the Folkwang Museum in Essen, and in 1928 he was invited to participate in the Venice Biennale, eventually becoming a member of thePrussian Academy of Arts in Berlin in 1931. However, he spent the rest of his life in the Alps, portraying rural landscapes and mountains and the inhabitants of the village where he lived with his life partner Erna Schilling, also experimenting with abstract art that reflected his goal of “participation of German art in the international modern style.” However, the German Nazis branded Kirchner as a"degenerate artist,“ along with other German expressionists and abstract artists, forcing him to resign from the Berlin Academy of Arts and seeing a large number of his works withdrawn from museums and collections. Apparently there were as many as 639 of them, of which 25 were diverted to Munich to be displayed in the 1937 defamatory exhibition ”Entartete Kunst" (Degenerate Art), organized for propaganda by the National Socialist Party. The traumatic impact of these events led to his suicide on July 15, 1938.

Kirchner’s style and major masterpieces

Now regarded as one of the most important artists of the first half of the 20th century, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner experienced an obvious stylistic development throughout his career (he also worked as an illustrator and left some sculptural evidence), until he matured a very personal signature in his incisive use of color and the psychological tension expressed by his pictorial subjects. His rich production counts over a thousand canvases and drawings, watercolors, etchings, book illustrations and even interior decorations.

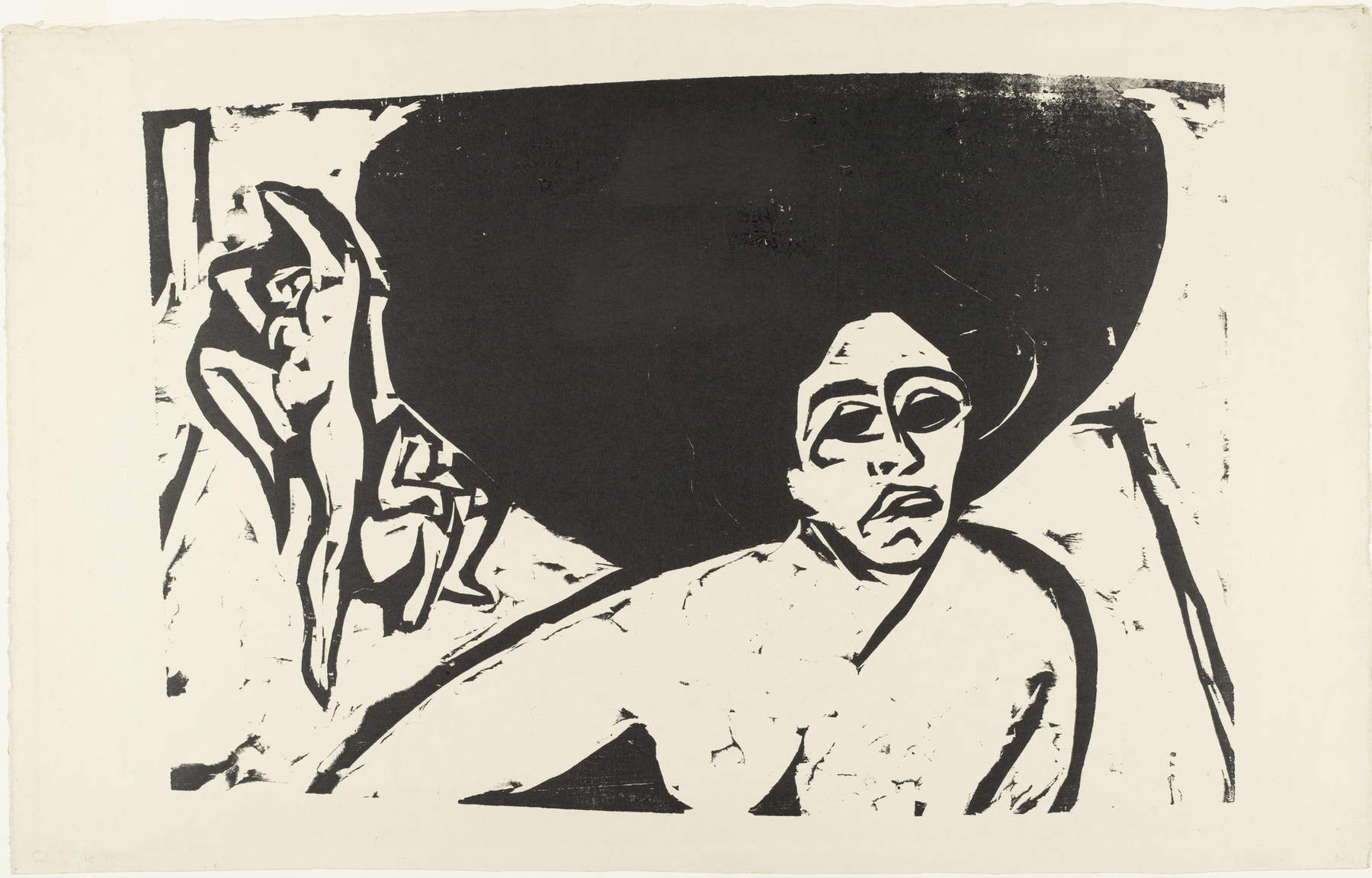

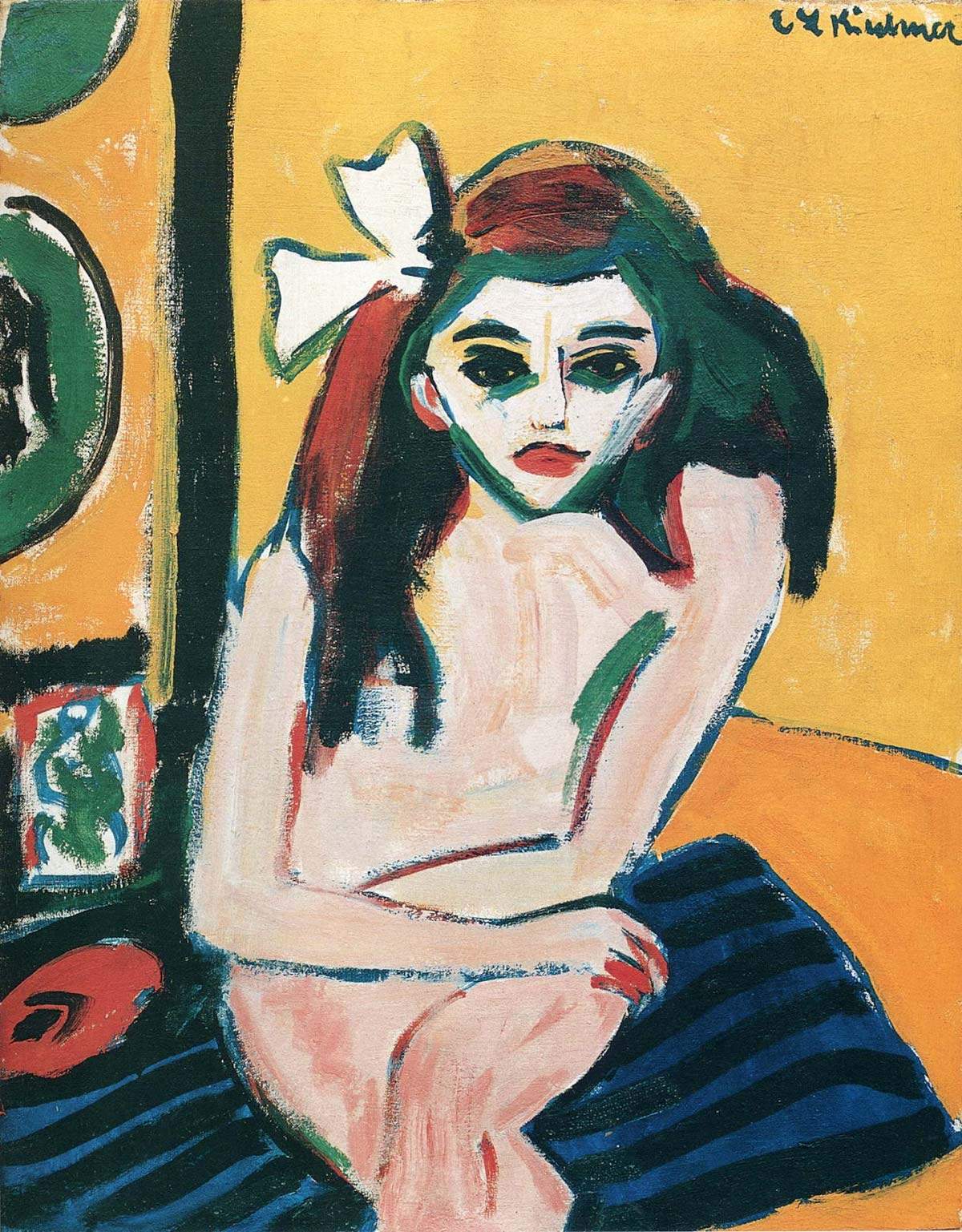

In his early years he concentrated on the nude genre, urban nightlife and studio portraits, and when during the summers he worked with the other artists and models of Die Brücke between Moritzburg and the island of Fehmarn, he also created many landscape works with groups of figures floating in nature: his style was characterized by the alteration of space and perspective, the definition of sharp, sharp outlines, often highlighted by strokes of black, and the use of strong, contrasting colors. The 1909 woodcut Nude Dancers is an example of this period and of the group’s utopian vision of a world untouched by encroaching industrialization and other alienating forces of modern life.

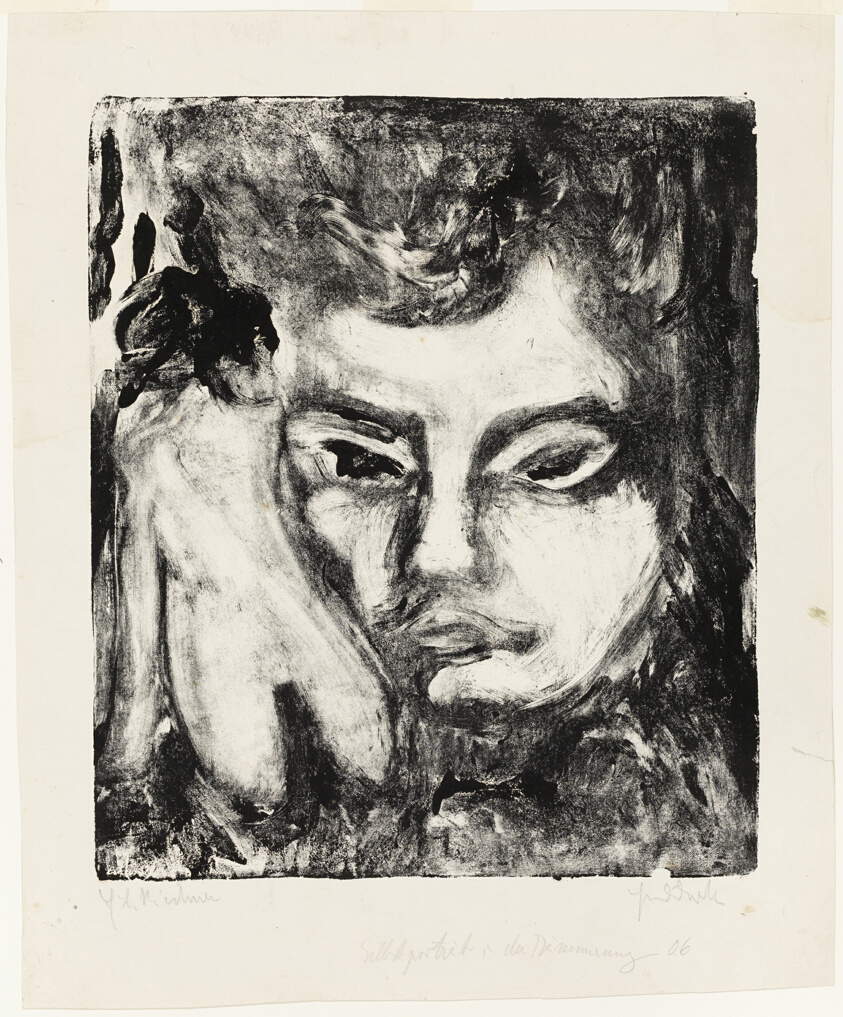

But when Die Brücke moved to Berlin, the ambiguous ambience of the big city, a claustrophobic feeling brought about by city life, reigned in his works above all, though always enlivened by a certain form of eroticism, latent or overt, at times threatening as with the nudes of earlier years(Bathers in Moritzburg, 1908; Head of Man with Nude, 1906 lithograph). Kirchner, as a witness to urban frenzy, with emphasis on subjective feelings, will identify scenes with the names of avenues, streets and squares(Nollendorfplatz, 1912). The main theme will remain urban “colorful life” with its different samples of humanity.

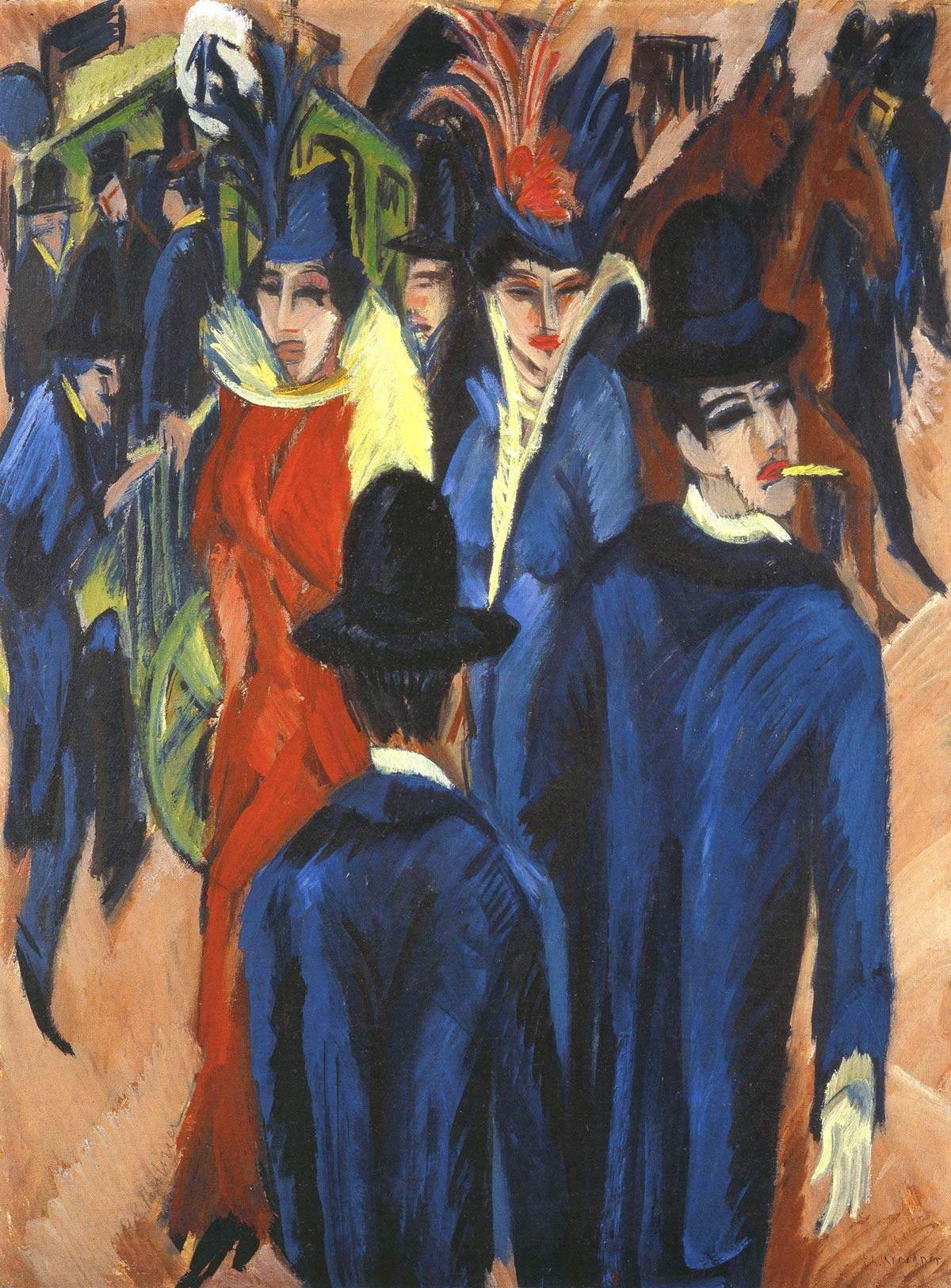

The series of oil paintings Street Scenes with strong coloristic contrasts is the most emblematic of his Berlin production, of which Five Women in the Street, 1913, is the first painting. The curvilinear rhythms of elegant women strolling on the sidewalk, ready to attract possible nocturnal customers, dominate the scenery of the capital just before the war; accentuating the sensual and primitive attitude of the bodies are the wild, dark contours of the figures with mask-like faces. Other masterful works from that time include woodcuts for “Der Sturm,” Germany’s leading avant-garde periodical before World War II, or illustrations for Adelbert von Chamisso’s novel Peter Schlemihls wundersame Geschichte (“Peter Schlemihl’s Extraordinary Story,” 1915) and for the poet Georg Heym’s poem Umbra Vitae (1924), considered among the finest engravings of the 20th century. Later, having disbanded the group, when following the war Kirchner moved to Switzerland, here, faced with solemn alpine views he took on a more monumental style, where the often allegorical landscape and its sparse inhabitants became the favored subject (the last is Flock of Sheep, 1938).

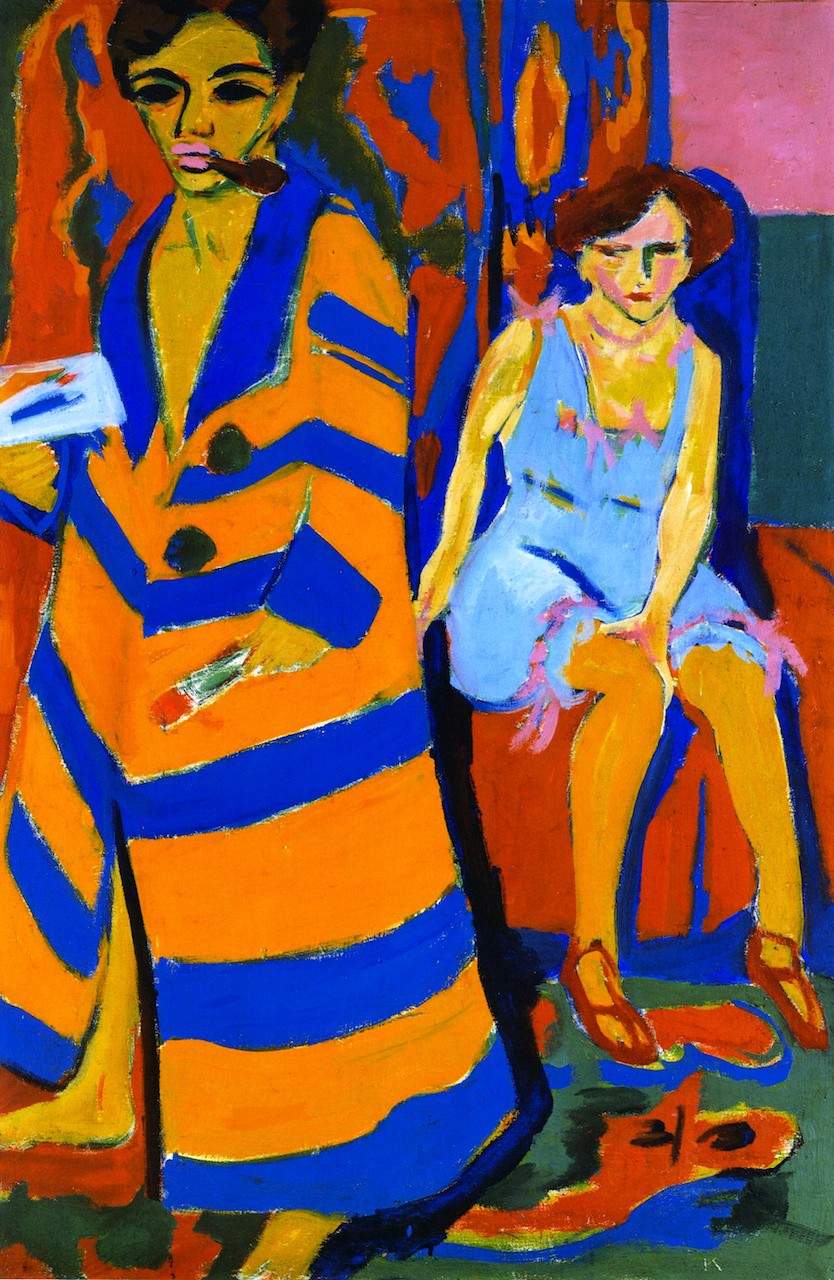

Overall, central to much of his entire output is the human figure. Crucial to the images that have his studio as a backdrop, images in which he captured posed models and aspects of his bohemian life, and to the Berlin scenes, in which the behavior of bodies on the street seem more important than the surrounding urban landscape. Human presence often depicted in motion, in the fullness of the vitality of the human body. Kirchner believed that powerful forces, life-giving but also destructive, dwelled beneath the frenzy of Western civilization, and he believed that creativity offered a means of representing them. This belief determined the way he depicted men and women as people who often seem at war with themselves or their environment. Powerful self-portraits likewise document his moments of crisis.

African and Oceanic primitive art was important in directing Kirchner toward a more simplified treatment of forms, just as French Fauvism was particularly significant in directing his palette, encouraging him to use flat areas of unbroken, often unmixed color, as evidenced by works that also bear the resonance of two-dimensionalism and the motifs of Japanese prints(Girl under a Japanese Sunshade, uncertain date 1906 or 1909). Certainly the most deeply rooted influence throughout his career found him from the graphic art of German artists of the medieval and Renaissance periods, and from the even sculptural examples of Albrecht Dürer, later revisited(Dancer, 1911).

Where to see Kirchner’s major works

The artist’s works are preserved today in most museums of modern art in Europe and the United States, as well as in important private collections. Starting with the Kirchner Davos Museum in Switzerland, which has a large collection of his paintings, drawings and watercolors, woodcuts, engravings and lithographs, textile works and wood carvings that testify to the Die Brücke era, the war years from 1915 to 1918 and the Swiss period.

Another important nucleus of works is at the Moma - Museum of Modern Art in New York, which holds more than 170 of his works, including one of the Street Scenes in Berlin. In fact, the series is divided, and works can be found at the Neue Galerie, also in New York, as well as at the Folkwang Museum in Essen and at major German institutions, where numerous other masterpieces of his can also be seen: at the Neue Nationalgalerie and the Brücke-Museum in Berlin, the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, and the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, to name a few. Famous paintings are, Marzella of 1909-1910 at the Moderna Museet-The Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm, Self-Portrait with Model of 1910 at the Kunsthalle in Hamburg, and Self-Portrait as a Soldier of 1915 at the Allen Memorial Art Museum Oberlin in Ohio.

|

| Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, life and works of the German expressionist painter |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.