Egon Schiele, the artist of finis Austriae. Life, works, style

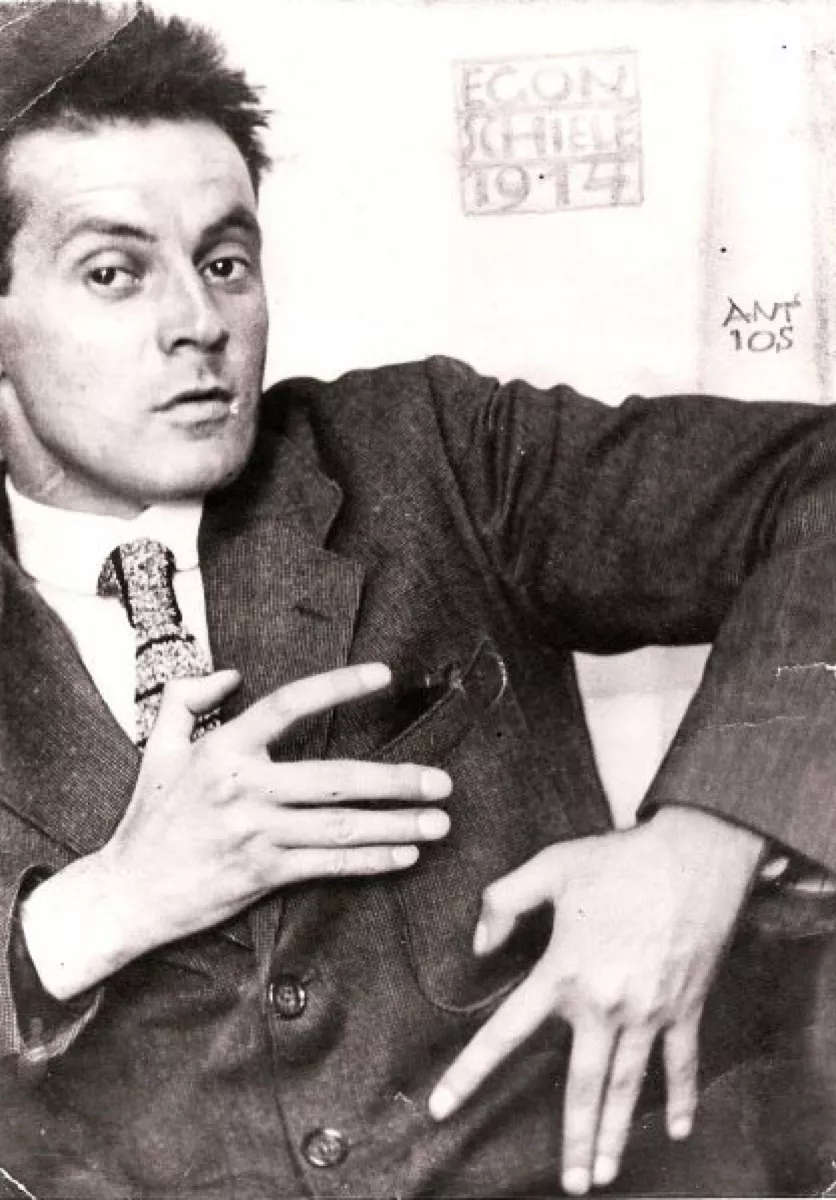

Egon Schiele (Tulln an der Donau, 1890 - Vienna, 1918) was an Austrian painter, witness and cantor of the “finis Austriae.” Together with painters Gustav Klimt and Oscar Kokoschka, he marked the European art scene by bringing Secession Vienna back as a protagonist.

Although presenting himself as a continuer of Klimt’s art, as might appear at first glance from the restrained elegance of his nudes, Schiele soon distinguished himself from the master by the angularity of his forms and the vibration of his sign. Schiele’s bodies and figures exhibit a dryness and aridity that foreshadow the developments ofGerman Expressionism, an artistic movement that made its appearance with the Die Brücke group in Dresden.

Life of Egon Schiele

Schiele was born in Tulln on the Danube, in Lower Austria not far from Vienna, on June 12, 1890, specifically in a train station, where his father Adolf Schiele worked as a stationmaster. His father’s story was relevant to the formation of the artist’s character: in fact, suffering from a mental illness, he died early; this event deeply marked the painter’s childhood, his way of seeing and perceiving the reality around him, and therefore his work. After his father’s death, Schiele was entrusted to his uncle Leopold Czinaczek, a wealthy man who noticed his artistic talent and therefore, supported his education.

In 1906, at the age of sixteen, Egon Schiele began studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. The city at the time was experiencing considerable cultural ferment. Rich and stimulating, dynamic in its intellectual offerings, Vienna was alight and appeared more vibrant than ever, moreover shaken by the presence of independence movements. Attending courses at the Viennese Academy did not prove too useful for the evolution of the artist’s genius, which felt occluded, confined to the pressures of more traditional and academic research. So it was that Egon Schiele began to look beyond the academic zone to more stimulating environments for him, such as the Viennese cafés that were gathering points for more extravagant personalities well disposed to experimentation. At the Café Museum in Vienna, precisely, Schiele made his most important encounter with the painter Gustav Klimt, under whom he began his personal artistic quest. The two also became close friends and nurtured mutual esteem, sharing an interest in nude figuration and the depiction of sexuality. Schiele focused heavily on the human figure, absorbing the decorative tendency from Klimt. His proximity to the master of the Viennese Secession enabled the artist to gain a certain clientele, meeting patrons and collectors who were immediately attracted to his work. This assured him a certain economic stability.

Thus in 1903 Schiele held his first solo exhibition in the Wiener Werkstätte, designed by architect Joseph Hoffmann and graphic designer Koloman Moser. The art circle was based on the idea of the total work of art. In his early works there are already all the elements that foreshadow the style for which he later became iconic: sinewy, dry lines forming erotic-looking nudes. He exhibited again in 1909 in a group show at the Kunstschau, and in the same year he founded the Neukunstgruppe with other artists, breaking away from Klimt’s Art Noveau style. Schiele also drafted a theoretical manifesto for the new group: "The artist of the Neukunstgruppe must necessarily be himself, must be a creator, must be able to create his own artistic foundations, without using all the heritage of the past and tradition." The artist also exhibited at the famous Salon Pisko exhibition, where Archduke Franz Ferdinand was also present without showing interest in his works.

From 1910-11 Schiele moved between South Bohemia and the Viennese countryside; during this period he

he also experienced life in prison as a result of accusations of molestation and kidnapping but really more for the content of his works, which were considered pornographic and sexually explicit by the authorities of the time. His Diary from Prison was first published in 1922 and here he recounted this experience. The painter returned to the city for good in 1913, where he regained ground on the art market, again with the help of his friend Gustav Klimt. In 1914 the painter married the third and last of his models, the marriage introducing him to a serenity that emerged and was visually felt in his paintings.

Just as Schiele was establishing himself in the art market, World War I broke out. A subsequent move led him to participate in the forty-ninth exhibition of the Vienna Secession and he exhibited again in other cities. Despite the aftermath of the war conflict, it was a period of great stability as seen in the painting production itself. Unfortunately, in 1918, the outbreak of theSpanish flu also hit Vienna, taking away his wife Edith, who was six months pregnant, and Egon Schiele himself just three days later.

Egon Schiele’s Style and Poetics

Egon Schiele was a prolific painter between paintings and watercolors, and tormented, who experienced success but also more difficult phases, amid scandal, banishment from society because of the content of many of his works, often of explicit eroticism. In his short life, cut short like that of the painter Gustav Klimt by the 1918 epidemic, he confirmed himself as a protagonist ofAustrian expressionism. This was a movement that took on aestheticizing overtones, deriving from Germany and spreading to Austria, little by little it was woven into the declination of the local Secessionist Symbolism that found in Klimt its leading exponent.

In Schiele’s work, the Secessionist experience reveals its influence in the fact that Expressionism retains its vehemence unchanged but accommodates a taste for preciosity, a decoration of a formal kind that gives the works the estheticizing veil. Unlike German expressionism, in fact, Austrian expressionism applies itself in the pursuit of a refinement of sign, rather setting aside violent color rendering.

The themes addressed are also different, resolving themselves in giving expression to intimate and subjective experiences. These themes are often treated with evident sensitivity, bordering on exasperation. Among the aspects investigated is also a denunciation of situations indicative of the reality of the time, circumstances that the Austrian expressionists condemn through the exploration of consciousness and the unconscious, territories in which tensions of contemporary society reverberate. In this pursuit, Schiele first focused his interest on the human figure, drawing from Klimt the inspiration to decorative composition, the interest in graphic refinement, as seen in some drawings, where fabrics often render floral motifs close to Klimt’s work.

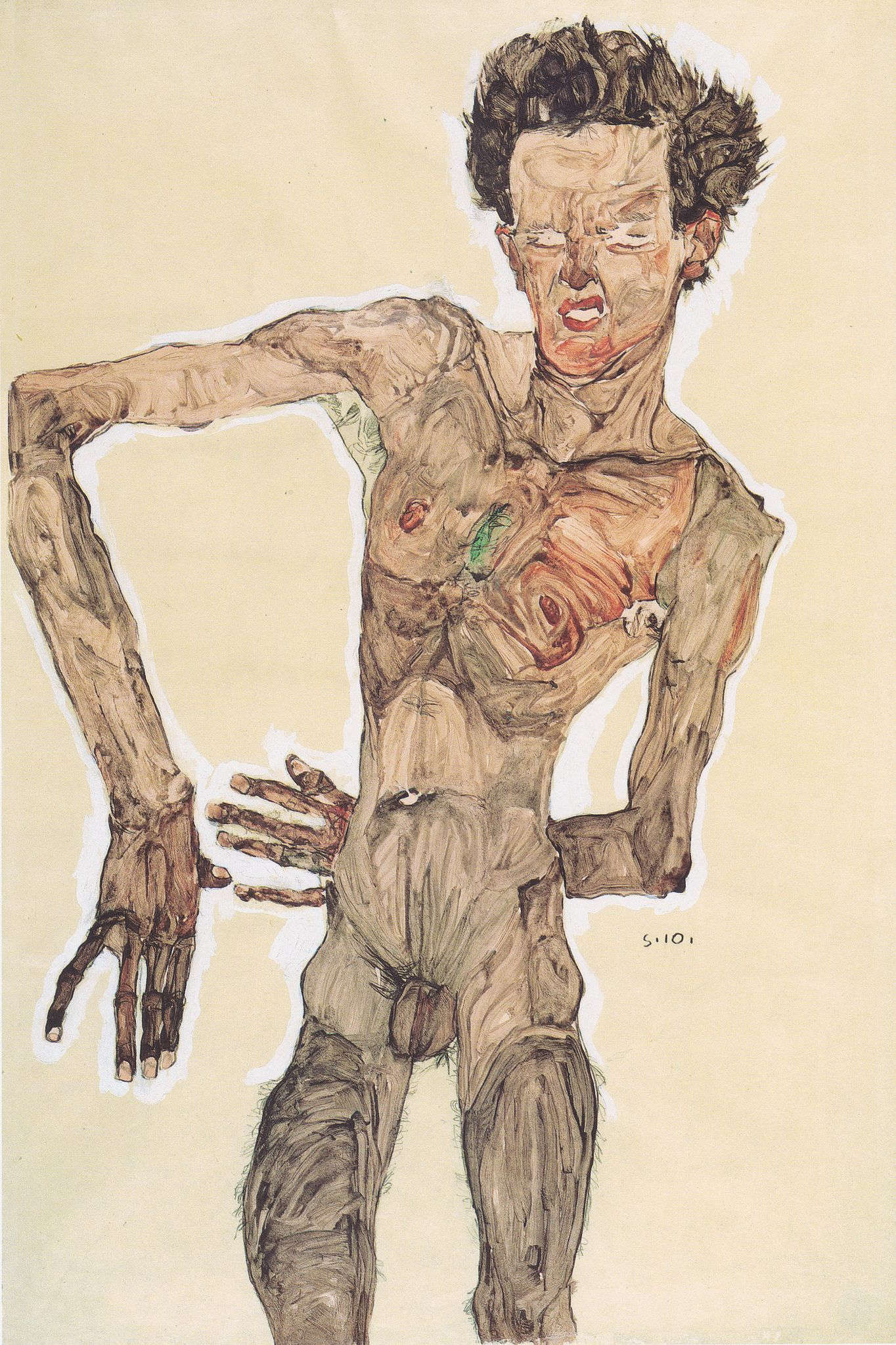

In general, Schiele’s paintings are always charged with emotional tension. In a 1910 canvas, Self-Portrait, the painter renders all his restlessness in brushstrokes that are lightly charged with color but have an incisive stroke. The linearity of the figure is dry and angular, the face defined by few marks yet evidently contracted into a grimace that renders all the anguish and dissatisfaction. During these years Schiele created many figure studies using his own body in the mirror as a model: beyond the self-portraits, there remain many drawings that are bravura exercises in expressionist imagery of figure and body. The body is inspired by modern dance, the interiority manifests itself through contorted gestures, bony physiques, unexpected angles and perspectives. Fitting in this regard is Male nude with red sash encircling the hips, a 1914 watercolor preserved in the Albertina in Vienna.

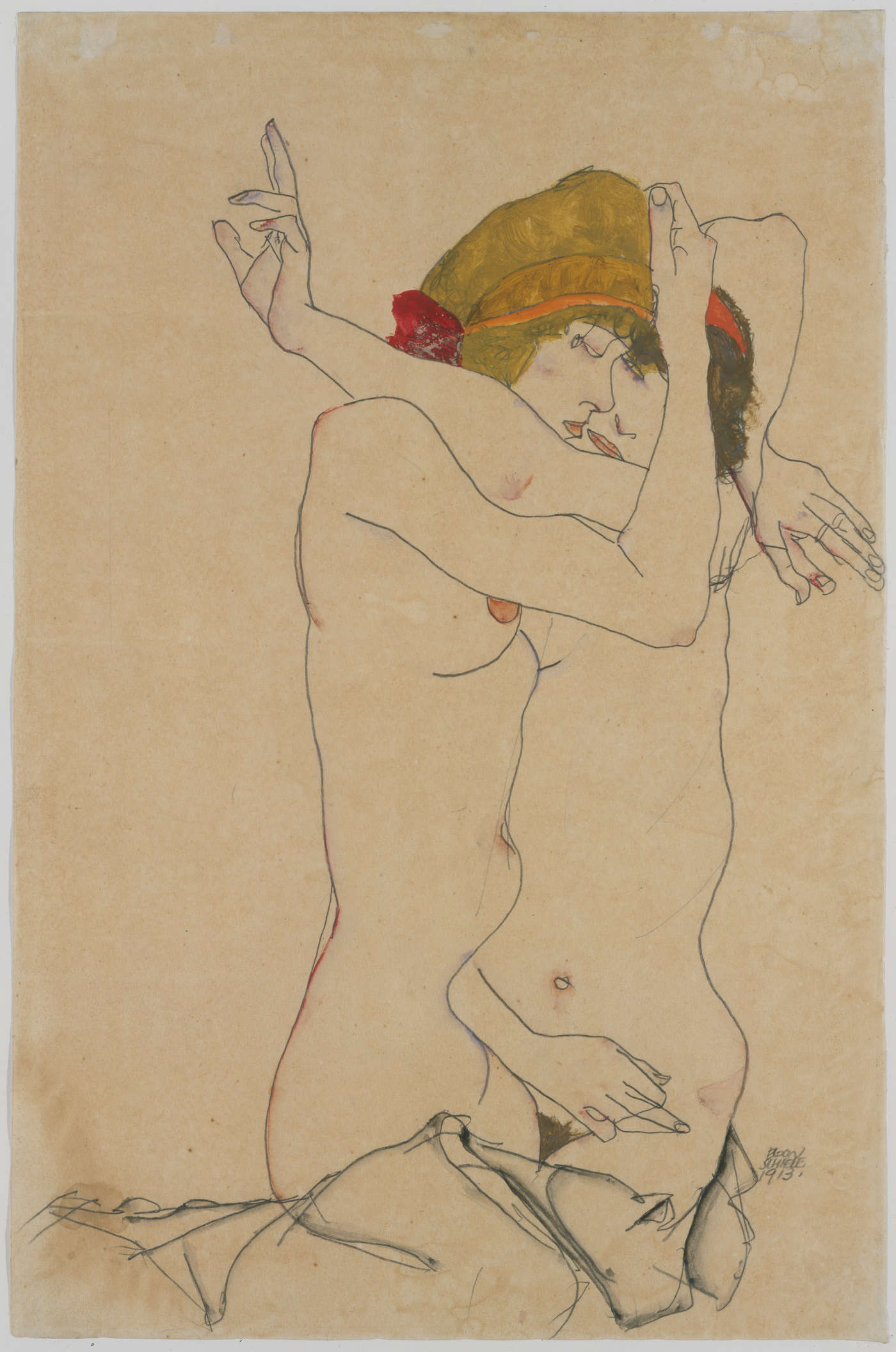

In particular, Schiele’s artistic production focuses heavily on the female figure, between nude drawings and portraits of magnetic, intensely attractive women: in Seated Woman with bent knee (1917), the girl’s gaze defies the material limit of the canvas, interrogates and invites the viewer, who feels attracted and drawn in.

Much of the production is then devoted to the depiction of intimate moments of the couple, caught in the deepest exchange. Schiele’s temperament in challenging and provoking the society of the time can be traced in his paper-and-pencil work, Two Women Embracing, from 1915, made at the height of the World War. The depiction of bodies and their internal attrition is never just an exploration of human motions but also a provocation and manifestation of contemporary events.

In the canvas Death and the Maiden (1915-1916), Schiele depicts himself together with his lover Wally in a moment of great sadness due to their choice to separate. Klimtian linearity here is transformed into an exaggerated interlocking of arid forms and nervous marks. The colors, more dear to German expressionism, are here reduced to a few somber hues and lacking in material density, but functional in accentuating the sense of despair that pervades the scene. Above a sheet, almost a shroud, is crumpled and thrown over the stony ground. The young woman clings to the dark skeletal figure in a mortal embrace that is, at the same time, a re-presentation of the dualism between Eros and Thanatos (Love and Death), a theme dear to Symbolism and also a metaphor for the historical situation of Austria, now nearing the end of the empire. Among the scenes of couple intimacy is the famous Embrace of 1917, exhibited at the Belvedere in Vienna.

Where to see the works of Egon Schiele

Most of Egon Schiele’s painting production can be found in Vienna: theEmbrace is on display at the Belvedere Museum, as are Death and the Maiden and other portraits.

At the Albertina Museum in Vienna, the self-portrait from 1910 is on display, and in the Graphische Sammlung of the same Albertina is the Male Nude with a red sash encircling his hips. Also in Vienna, many of the painter’s paintings are kept at the Leopold Museum, including the famous Self-Portrait with Alchechengi (1912) and the Portrait of Wally Neuzil (1912).

Leaving Vienna, at the National Gallery Prague, one can encounter the Seated Woman with bent knee from 1917. Overseas, a substantial core of graphic material, with various portraits of the painter, are preserved at the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

|

| Egon Schiele, the artist of finis Austriae. Life, works, style |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.