Edvard Munch (Løten, 1863 - Oslo, 1944) was one of the most important artists active between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries because together with other painters of his age he marked a turning point in art history. Whenever we cross his name in a book or exhibition he is always flanked by two other artists: Paul Gauguin (Paris, 1848 - Hiva Oa, 1903) and Vincent van Gogh (Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890). One might think that these three masters are united in the first instance by their lack of success in life and posthumous fame, but this is actually a mistaken opinion. In fact, although it is a common thought to associate Edvard Munch’s darker works and sad biographical story with low popularity in life, the Norwegian achieved great success in the latter part of his career. In fact, what the three artists have in common is the subjective charge that characterizes their works, capable of going beyond that scientific and objective study of reality carried on by the contemporary currents of Impressionists and Pointillists. It is no coincidence that Munch, Gauguin and Van Gogh are considered forerunners ofexpressionism, that artistic current that aims to enhance the emotional side of the reality that surrounds us.

Munch’s greatest masterpieces are the result of a tormented and painful life, marked by family loss, setbacks, alcoholism, neurosis and loneliness. As will be seen later, Munch’s life was full of ups and downs, which did not allow the artist to achieve the mental and emotional stability that his economic and social status would have allowed him. Indeed, despite his troubled and lonely life, Munch was a great success with European critics and audiences, to the point that many artists, for example, the Die Brücke and Fauves avant-gardes, recognized him as a father and master of their art. However, trying to label the art of the Norwegian genius is an impossible task because of its singularity and also because Munch himself refused to be lumped in with any group of artists.

Edvard Munch was born on December 12, 1863, in Løten, a small Norwegian town near Christiania (the original name of Norway’s capital Oslo), the second of five children of Christian and Laura Catherine Bjolstad. In 1864 the family moved to Christiania, where the painter had the opportunity to come into contact with a broader cultural landscape than in his small home town. Unfortunately, Edvard’s childhood was marked by various mournings, beginning with the deaths of his mother in 1868 and his older sister Johanne Sophie in 1877, both caused by tuberculosis. In addition, the untimely loss of his mother led Edvard’s father to a mental breakdown that estranged him from his children. This profoundly affected the relationship between the young Munch and his father, who dreamed of an engineering career for him, but to which Edvard preferred art, so much so that he began taking courses at the Royal School of Drawing.

In 1882 Edvard Munch and other painters rented a studio together and entrusted their training to two distinguished painters: naturalist Christian Krihg and impressionist Frits Thaulow. The latter’s works inspired some of the paintings exhibited in 1883 at the Salon of Decorative Arts in Christiania, the first exhibition in which the young Norwegian painter participated.

In 1885 Edvard Munch moved to Paris, where he first read the works of philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. The latter theorized different ways of conceiving existence; these included the “aesthetic life,” which was based on the combination of art and life, which Munch reinterpreted in a personal key as art and pain. This Parisian period was pivotal in several respects: in 1889 Munch organized his first solo exhibition, and although it was a failure, he obtained a scholarship that allowed him to stay and live in the capital. The French sojourn was also an opportunity to make himself known through a number of exhibitions, but above all to come into contact with the works of a great many artists, particularly those of Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, which prompted him to search for a personal style that would set him apart. However, these years were also marked by the loss of his father, an event that tormented the artist until the end of his days, as he had been unable to mend his relationship with him. It was precisely this situation that marked a turning point in his works, which continued to be exhibited for a few years but failed to make their mark on the art scene.

The year 1892 was extremely relevant to Edvard Munch’s life and career. The Norwegian painter was invited by theBerlin Artists’ Association to exhibit at their annual exhibition. However, the exhibition lasted only a week because Munch’s works were deemed scandalous and obscene by the authorities. The measure caused wide dissent, to the point that a group of artists from the fellowship, led by artist Max Liebermann, decided to split from the Berlin Artists’ Association in 1898, forming the famous Berlin Secession.

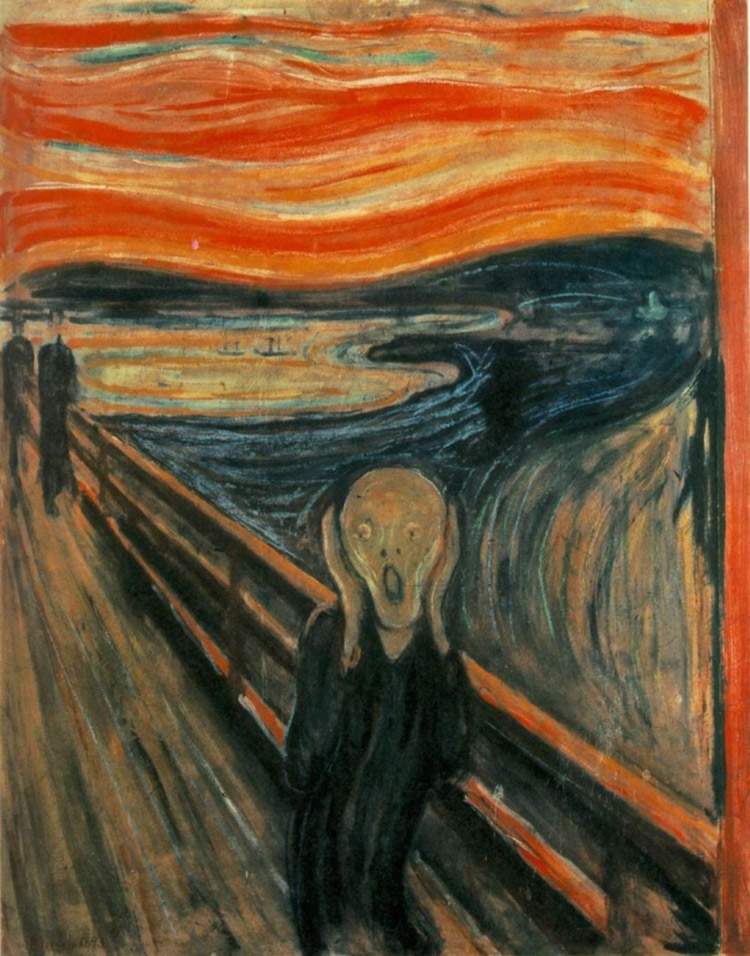

Censorship did not constitute a setback in Edvard Munch’s career, however. In fact, the artist was able to understand the importance of the episode and thus decided to settle in Berlin. In the German capital, the Norwegian was recognized as a great painter because of the unique character of his works, which allowed him to exhibit throughout Europe and even in the United States. The year 1893 was one of the most important years of his career for the production of some of his greatest masterpieces, such as TheScream(read a brief literary and philosophical background on the painting here), which were characterized by phosphorescent, phosphorescent hues and macabre, disturbing subjects. During an exhibition Munch decided to group six works into a series titled Love, the original nucleus behind the Frieze of Life: a unified cycle of paintings that was expanded in the years that followed until its final form in 1902. Although on the one hand Munch reached the peak of his career in 1893, on the other his troubled relationship with his fiancée Tulla Larsen ended tragically. Also in the same year he began to devote himself to graphic and photographic works, which were widely successful.

In the years that followed, Munch traveled extensively and achieved a certain fame, to the point that various groups of artists proposed that he join them. However, Edvard always declined the invitations, preferring to live alone, sinking into an unstable and exasperated mental state, aggravated by alcohol abuse. Despite the terrible situation, the artist understood on his own that it was no longer possible to continue living in this state and decided to hospitalize himself, albeit with the possibility of continuing to paint. After his hospitalization, Edvard was able to lead a healthier lifestyle, but still in solitude. In fact, the painter decided to isolate himself almost completely from the rest of society. The last years of his life were marked by an attempt to be appreciated by his motherland, which had always ignored him, by engaging in public commissions and bequeathing most of his works to the mayor of Oslo. Soon after reaching an agreement with the mayor, Edvard Munch died in 1944 from bronchopneumonia.

The works of Edvard Munch’s early period are very different from those of his maturity: the hues are soft and controlled, the characters are calm and relaxed, and they are still influenced by the art of Edvard Degas, who was an important artist for him in the early years of his career. A turning point is clearly discernible in the work The Sick Child (1885-1886). This painting was first exhibited under the title Studio and aroused much controversy from critics because of the unfinished and unfinished character of the pictorial material. The work reflects a personal event, namely that of the death of her sister, who appears to be depicted on her deathbed next to her Aunt Karen, who at the time took care of the children after their mother passed away. Although the painting is only from 1885, Munch’s brush seems to be breaking away from the Impressionist style and moving closer to a more subjective and emotionally charged type of painting.

As mentioned earlier, 1892 was the turning point in Edvard Munch’s artistic career. This can be sensed in some works from these years, such as Melancholy. The work depicts a seascape at sunset, with a pier in the background, where some figures and a boat in the middle of the sea are depicted. In the lower part of the canvas, on the right, appears a man identifiable as Munch, with his ear resting on his left hand-the typical pose of melancholy. The painting draws inspiration from the love disappointment felt by a friend for a painter he loved. From this painful experience, the Norwegian master draws inspiration to create a work that represents the anguish and pain felt by every person at least once in their life. In addition, it is possible to see how the tones are darkened and the feeling of melancholy is conveyed through broad, hasty color backgrounds.

The same technique can be seen in another work from the same year, Evening on Karl Johan Avenue. The painting depicts the typical bourgeois ritual of the evening stroll in the city of Christiania. Munch does not dwell on depicting the anatomical details of individual passers-by, but represents them as a single block of blank-eyed automatons, proceeding in the same direction. The only one who separates himself from this shapeless mass is a man in a top hat walking down the street in the opposite direction: this is Munch himself, who always felt marginalized and distant from society.

Over the years, the Norwegian artist’s works became more simplified and the colors became brighter and more vibrant, with the purpose of illuminating the canvas and suggesting the feelings felt by the painter at the time of execution. These are strong and terrifying emotions: jealousy, anguish, melancholy, despair and libido, which underlie numerous works laden with symbolic meanings that allude to personal feelings and events. Beginning in 1893, Munch decided to collect several paintings within a single organic collection that took the name Frieze of Life, a narrative of his spiritual and emotional affairs. Initially the Frieze was composed of five paintings, with the title Love. Later, Munch added more works to this collection until there were twenty-two paintings for the fifth Berliner Secession. For the exhibition, Munch divided the Frieze of Life into four stages: the Seed of Love, Development and Dissolution of Love, Anguish, and Death.

Among the works in the Frieze of Life also appears the most famous painting in Edvard Munch’s entire body of work: theScream. The world-renowned work is once again the transposition into painting of a firsthand experience of the artist, a written account of which can be read: “I stopped to look across the fjord, the sun was setting, the clouds were dyed blood red. I heard a scream go through nature: I almost felt as if I could hear it. I painted this picture, painted the clouds like real blood. The colors were screaming. This became The Scream.” The painting depicts the Ekeberg Fjord, a destination for Sunday walks and a typical postcard scene. Once again Munch breaks with tradition and transforms a familiar place into an earthly hell: the sky is tinged with blood red and the man in the foreground, far from the other two figures on the left, struggles in a painful and terrifying scream in response to the distortion of nature around him. The work cannot help but create anxiety and a sense of disturbance in the viewer’s soul, who remains petrified before the author’s cry denouncing a social anxiety that accompanied him throughout his existence.

A recurring theme of the Frieze of Life is women, who always represented a sinister and ambiguous role in Munch’s imagination. Among his most famous works are The Vampire (1893-94) and Madonna (1894), which represent two distinct personal visions of the female figure. Initially the painting the Vampire was called Love and Pain by Munch, and the artist himself stated that it was “only a woman kissing a man on the neck.” Only later did his friend and biographer Stanislaw Przybyszewski rename the work to its present title, in reference to the woman’s demonic and subjugating view of the man. In fact, in the painting the man sacrifices his own life by surrendering to the deadly kiss because he is thirsty for the amorous desire, which only the female figure can satisfy. The second painting is surely one of the most scandalous in all of art history. In fact, Munch depicts a Madonna who is anything but a virgin and distant from the classical depiction of this subject. The woman is portrayed in a sensual and provocative pose. The artist produced five versions of the work, including the example in which the frame is decorated with spermatozoa, while the figure of an abortive fetus appears at the bottom left, recalling the mystery of birth and the dogma of virginity. The work aroused great outcry and was met with harsh criticism from the benighted public of the time.

Despite the scandals and tensions aroused by Munch’s works, his contribution was fundamental to the Expressionist movement: as also mentioned above, the baton of his experience would later be picked up by the Berlin Secession. Above all, the names of Lovis Corinth, Max Liebermann, and Käthe Kollwitz should be mentioned, who looked to Munch with conviction and in some cases even succeeded in arousing scandal exactly as their forerunner had done.

To learn about the works of Edvard Munch, it is necessary to plan a trip to Norway, where almost all of his works are collected. Much of it is collected within the Munchmuseet in Oslo. The Nasjonalgalleriet in Oslo, the first public institution to acquire works by Munch, also has an entire room dedicated to him, inside which is housed the most famous version of TheScream. Finally, eleven of Munch’s oil paintings, the result of a competition won by the painter, are housed in the Great Hall of the University of Oslo. However, it is also possible to admire some works outside the Norwegian borders: for example, one of the versions of the famous work The Sick Child is kept at the Tate Modern in London.

|

| Edvard Munch, the life and works of the Scandinavian genius |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.