Ã?douard Manet, between realism and impressionism. Life, style, works

Édouard Manet (Paris, 1832 - 1883) was a French painter of great importance at the time of the transition from the Realist to the Impressionist current. His paintings were much criticized by the public contemporary with him as being decidedly different from what was already known and often provocative. Indeed, the public was bewildered to see glimpses of real life in Paris on the canvas and people on the margins of society given the same importance as previously reserved for major historical themes and heroic figures. Moreover, Manet reworked great masterpieces of the past, which he knew thoroughly having studied and copied them with accuracy (it is well known, for example, how Breakfast on the Grass is a reworking of Titian’s The Country Concert ) to place them in contemporary society, drawing harsh accusations of disrespect for the great masters.

Manet’s works did, however, win praise from writers and other artists. He was appreciated and praised by Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne and others, while in turn he greatly admired Gustave Courbet among contemporaries and Francisco Goya and Diego Velázquez among artists of the past. Today Manet is universally regarded as one of the greatest and most celebrated painters known throughout the world.

The Life of Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet was born in Paris on January 23, 1832 to a very wealthy and cultured family, as his father Auguste Manet was an official in the Ministry of Justice, while his mother Eugénie-Desirée Fournier was the daughter of a diplomat. Édouard was born a year after his parents’ marriage and was the eldest son. After him, two younger brothers, Eugène and Gustave, were born. The Manet family lived near the École des Beaux-Arts, yet the father did not like painting at all and, in fact, tried to dissuade his son when his passion for the arts became apparent. It was a maternal uncle, Édouard Fournier, who instead did his best to encourage his nephew to paint, and often took him on visits to the Louvre so that he could practice copying the great masterpieces of the past. In particular, Manet favored Francisco Goya, El Greco, and Diego Velázquez.

Manet’s achievements as a student were very poor and he spent his time more drawing than studying, but even this did not convince his father to let him cultivate his talent, and once he finished boarding school, he insisted that his son enroll in law school. However, Manet began to rebel and decided to pursue a naval career rather than give in to what his father dictated. However, the lure of drawing remained ever-present in Manet who, having embarked on a merchant ship bound for Brazil, spent all his time drawing sketches of landscapes and portraits of fellow passengers, filling numerous notebooks. Eventually, Manet’s father had to resign himself and allow his son to study art. Édouard then began practicing in Thomas Couture’s workshop, and during his six years there, marked by numerous disagreements between him and the master born of opposing views on art, he lost no opportunity to make several study trips around Europe, continuing to copy past masterpieces as he did in his youth at the Louvre. He went to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam in 1852 to copy several paintings by Rembrandt, and the following year he left with his brother Eugène for Italy, visiting Venice and Florence.

Upon their return to Couture’s studio, the final parting of ways occurred between the two artists, who were by then incompatible. Meanwhile, Gustave Courbet and his Realist painting was making more and more waves, and Manet became fascinated. He began to draw inspiration from Realism, but eliminated references to politics or particular ideologies. In addition, he asked and obtained from Eugène Delacroix, another painter he held in high esteem, to be allowed to copy his work Dante’s Boat. Manet, after all this research and turmoil, signed his first work in 1859, The Absinthe Drinker. The work was greatly appreciated, especially by Delacroix, yet to his disappointment it was not admitted to the Salon, the most important Parisian exhibition of the time. That same year, however, Manet had a peculiar encounter at the Louvre: he saw Edgar Degas while he was intent on making a copy of a Velázquez painting. Their shared passion for the Spanish painter brought them into contact and culminated in Manet’s reworking of the painting The Spanish Guitarist (1861), which met with much acclaim and helped bring Manet into the circle of artists who used to gather at the local Brasserie de Martyrs, among whom was Courbet. Manet always remained very detached from that milieu, however, as he hated being called a revolutionary bohemian and preferred to introduce innovative art by going through official channels.

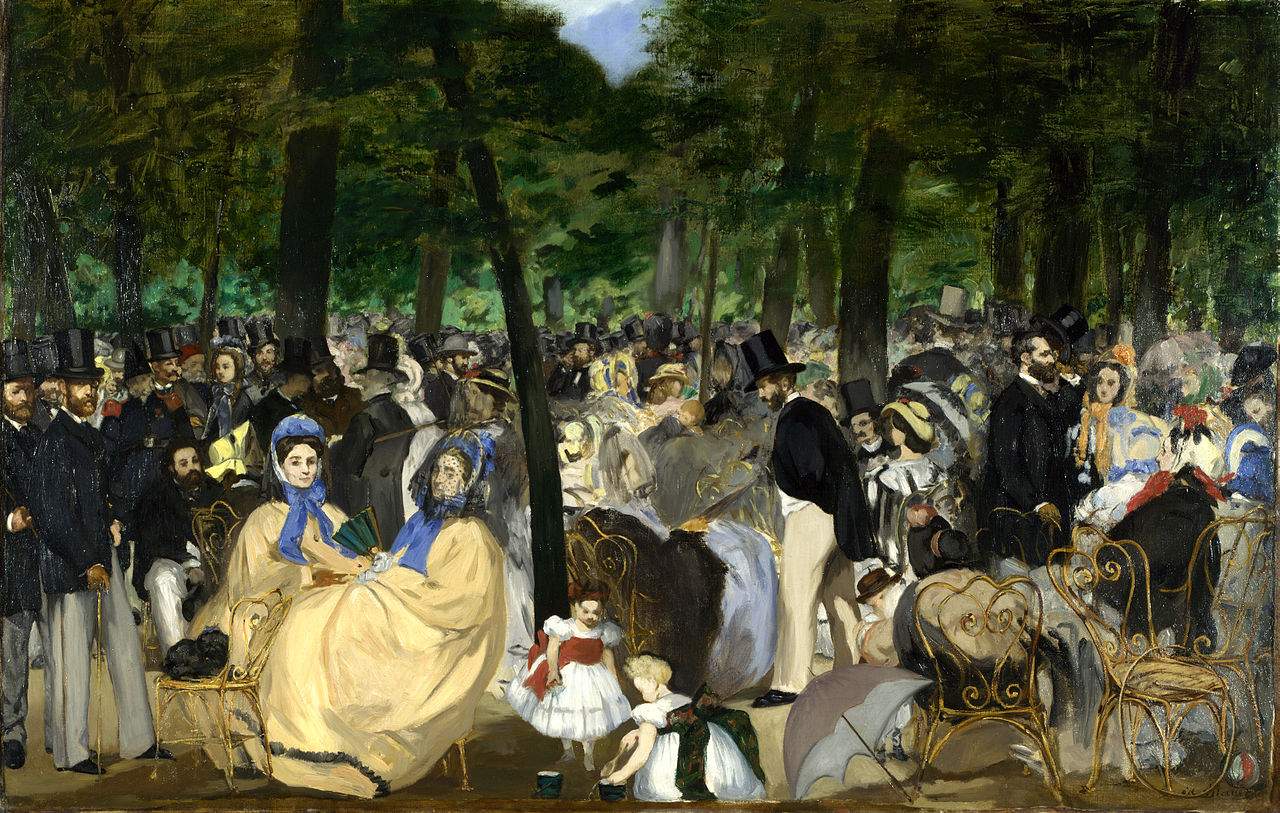

Yet it was through the Realists’ group that Manet came into contact with the poet Charles Baudelaire. The two immediately befriended each other, and Manet was deeply inspired by the essay The Painter of Modern Life and the figure of the so-called “artist-dandy,” whose task for Baudelaire was to succeed in fixing in his works the fleeting moments of the present. Manet sought to embody this figure and strove to create a work of a higher standard than he had achieved so far, namely Music at the Tuileries (1862). The work was exhibited the following year at the Galerie Martinet, as part of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, of which Manet was a member, but it was harshly criticized by the public, which led to the rejection of Manet’s and the Realists’ nominations for the next Salon. Courbet and other artists officially protested, gaining the attention of Napoleon III, who allowed them to organize the famous Salon des refusés, an exhibition including all the paintings excluded from the main Salon. Manet on this occasion caused much scandal by presenting Breakfast on the Grass (1863). The criticism Manet suffered conditioned the artist, who, embittered, destroyed many of his works in a fit of rage, and in 1865 he decided to leave for Spain, intending to admire the works of Velázquez preserved in the Prado Museum and stay there for a long time. He then returned to France shortly thereafter, declaring himself disappointed with Spain, which he had probably idealized too much. By then Manet was basically excluded from all Salons, but he found extraordinary support from writers, such as Émile Zola, who dedicated an essay to him in L’événement aimed at praising the painter’s ability to reproduce reality in its simplicity, without superstructure. After 1870, Manet was also praised by Étienne, or Stéphane, Mallarmé and Joris-Karl Huysmans, although the public continued to criticize him.

Manet, meanwhile, decided to devise a different strategy for the 1867 Salon, deserting it and setting up the “Personal Louvre,” an exhibition with all his paintings. The public response was one of strong derision toward the initiative and the works on display, but it won praise from a number of now well-known artists who were taking their first steps in art at the time, namely Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne and many others. Manet began to gather with them at the Café Guerbois. Disappointment at the failure of the “Personal Louvre” convinced Manet to return to the Salon in a more canonical manner, moved moreover by greater confidence in this exhibition given the presence of Barbizon painter Charles-François Daubigny on the jury. He presented this time a number of paintings with a historical theme.

1870 turned out to be an important year in French history, as the Franco-Prussian conflict broke out and Manet joined the artillery along with Edgar Degas. France emerged defeated after the renowned defeat at Sedan, and this episode led first to the birth of the Paris Commune, a temporary organization born of the people, and then to the proclamation of the Third Republic. In this historical context both the Salons and the École des Beaux-Arts were temporarily abolished, but in the meantime the Impressionist group was emerging. Manet, although frequenting them assiduously in their en plein air painting sessions, did not exhibit with them at the first exhibition in 1874, although he was officially invited. He continued to support them and help them in their painting, but preferred to continue participating in the reinstated Salons, in which he was punctually criticized because of prejudice against him due to the scandalous works of the previous years. A turning point for his reputation was the appointment of Antonin Proust, a journalist and politician who was Manet’s fellow student, first as a member of the Chambre des Deputes and then, in 1881, as Minister of Fine Arts, who intervened on the artist’s behalf so that he could be awarded the Legion of Honor.

However, for some time Manet had begun to have serious health problems. He had contracted syphilis some time earlier, which caused him major strains in his muscular coordination. Doctors advised him to leave Paris and move to the countryside to rehabilitate, and despite these difficulties and his impatience with rural life, Manet between 1881 and 1882 managed to complete his last work, The Bar of the Folies Bergère.In 1883 his condition deteriorated inexorably, and after becoming paralyzed and having his leg amputated due to gangrene, Manet passed away on April 30. He was given a solemn funeral, with a military picket in attendance and all his friends holding the casket-Antonin Proust, Émile Zola, Claude Monet and many others. His remains lie in Paris, in Passy Cemetery.

Édouard Manet’s style and works.

Subject to criticism and accusations of scandal by the public contemporary with him, Édouard Manet’s works were not actually easy to understand at the time. They were not fully realist, while at the same time anticipating later Impressionist works, in fact constituting a unicum in nineteenth-century art.

His training was quite peculiar. When he finally obtained his father’s approval for him to study art, Manet asked to join Thomas Couture’s workshop as a pupil. This was a rather unusual choice, since Manet from early on showed that he was not at all inclined to follow traditional painting, whereas Couture fully represented it, specializing in large historical scenes. Indeed, by 1847 Couture had depopulated the Salon with The Romans of Decadence, and he had been a pupil of Antoine-Jean Gros, himself a disciple of Jacques-Louis David. At the time it was precisely the Salon painters who dominated the French art scene, and what is more, the works presented in these biennial exhibitions often adhered to certain canons, i.e., they were all large, historically themed works. Manet eschewed this kind of canonical art, believing that Salon artists unnecessarily enclosed themselves in closed rooms with mannequins and posturing settings, when in fact there was much to paint in the world outside the ateliers. During his time in the studio with Couture, Manet often challenged him on precisely the impossibility of being able to paint nude subjects placed in landscapes from life. Despite arguments and disagreements, Manet remained to study with the master for six years.

Manet’s early works, then, come very close to Gustave Courbet’s innovation in the precise intention of bringing real, non-mythologized scenes to the canvas. This is evidenced by The Absinthe Drinker (1858-59), which features a decidedly anti-heroic figure, namely a notorious ragpicker who wandered around near the Louvre, a character on the fringes of society and rather seedy. As already mentioned, however, the big difference with Courbet lies in theabsence of any social denunciation, as Manet in the paintings reports scenes from Parisian life of the time, presenting them as if he were recounting salient and important news events. It was this that caused a great stir among the public, especially in the case of The Breakfast on the Grass (1862-63).

The painting depicts four people gathered together for a breakfast in nature near a pond, surrounded by trees and vegetation. They are two naked women (one in the foreground, contemptuously addressing the viewer, and one in the background bathing in the pond) and two men, well-dressed. The nude female figure is presented for the first time in painting for no apparent reason to justify her presence: in fact, she was not the mythological personification of some goddess, as artists before him were wont to do, but she could be any Parisian woman. This was a great scandal to the well-meaning Parisians of the time, perhaps even more shocked by the woman’s gaze, which seems to address them by confronting them with a body without veils for what it really is.

Although Manet was clearly inspired by past masterpieces in the composition of this work, in particular the arrangement of the figures traces Titian’s The Country Concert while the nudes and some of the plastic positions certainly come from Marcantonio Raimondi’s engravings from Raphael’s The Judgement of Paris , this did not spare him from even harsher criticism based on the accusation of disrespect for past masterpieces. In addition, the work’s two-dimensionalism was also a subject of discussion: Manet wanted to be inspired by Japanese prints, but this was instead interpreted as wanting to ignore reasoning and studies on perspective and three-dimensionality.

The criticism he received for this painting on the one hand wounded him, while on the other it convinced him to continue in his convictions by challenging the public through an equally controversial work: the Olympia (1863-65). The famous work takes up a motif that was quite common among artists of the past, which Manet was familiar with and copied, namely Titian’s Venus of Urbino , Francisco Goya ’s Maya desnuda , and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Grande odalisque . In all of these works, the protagonist is an unclothed woman lying on a mattress resting on pillows. But unlike the illustrious previous examples, whenOlympia was exhibited it caused an even greater scandal than Breakfast on the Grass, as it was quite blatant that the protagonist was a prostitute, and the public reacted as if they had been confronted with a contemptuous parody and mockery of the art they were accustomed to knowing. The girl in question had for that matter none of the sweetness and shyness of the other protagonists in the earlier works, everything on the contrary displayed her body proudly precisely because a commodity at that moment available to be bought and handled. The girl’s gaze itself shows no emotion, is algid, does not even try to entice the viewer to choose her company, presenting herself simply as available, and this contributed to exacerbating the feeling of unease felt by those looking at the painting. The details that confirmed the young woman’s identity as a prostitute were many, from the pink orchid in her hair to the girl’s name, which was typical among Parisian prostitutes at the time, as well as the jewelry worn, the courtesan’s shoes, and the quirk of the black lace tied around her neck; finally, the presence of the black woman as a helper was also an element that often identified prostitution scenes.

Again, the technique used caused a sensation, as it was totally different from what people had been used to up to that time. There is no trace of chiaroscuro or shading; rather, here Manet distinctly anticipates Impressionism by juxtaposing a series of colored blobs that only when viewed from a certain distance would take shape, becoming a bouquet of flowers presented by the helper to the young woman.The uproar caused by the two works contributed, in any case, to a great deal of talk about Manet and the Salon des refusés, increasing its fame albeit not for the reasons Manet would have expected.

There is a brief interlude in Manet’s pictorial production in which, due to the bitter disappointment of the “personal Louvre,” he decided to present some more canonical paintings of historical themes at the Salon, though consistent in presenting the episodes in a chronicled and unemphasized manner: The Fight between the Kearsarge and the Alabama (1864) and The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1868). In the second work in particular, Manet’s knowledge of Goya’s May 3, 1808 , depicting the same scene with different subjects, is evident. In the 1870s Manet came into contact with the Impressionists, and with them he devoted himself to various researches on the color palette, which turned out decidedly brighter and more vivid. Some outdoor painting sessions Manet did with them in the small town of Argenteuil, to which Manet dedicated some paintings, were certainly involved. As noted above, however, Manet preferred not to exhibit together with the Impressionists, convinced that he wanted to spread his art through the official channels that they avoided instead.

In 1881-82 Manet, by now debilitated in physique painted the last work that would later be to all intents and purposes his artistic testament, The Bar of the Folies Bergère. Here, a scene is depicted set in a Parisian café-concert, where the Parisian bourgeoisie often went to distract themselves by spending a moment of leisure. Among the patrons of these establishments was Manet, which explains the accuracy of the elements portrayed in the painting. Some details in the work are striking in that they are very daring. First, the scene is dominated by the presence of the attendant, portrayed as she waits to take an order. The girl is young, and rather elegantly dressed, almost looking like a Parisian aristocrat, but what “betrays” her is instead the somewhat ungainly way in which she leans against the bar counter. The young woman’s expression, moreover, comes across as melancholy and sad, hinting at how she is forced to do a job that she is not passionate about and that probably results in squalor.

Finally, the expedient of the mirror turns out to be interesting, in which it is possible to both see the rest of the salon, filled with men in top hats and elegant women as they are intent on watching the show (binoculars and especially legs are depicted; this was probably the trapeze artist performing a number and “enters” the painting) but most importantly it reflects the image of the patron who has gone to the counter to order, not visible in the first instance as the image is seen from her direct perspective. Even in Manet’s last work, then, Realism and Impressionism intersect in a distinctly personal way.

Where to see the works of Édouard Manet

Many of Édouard Manet’s works can be found in Paris, collected in the Musée d’Orsay, the famous exhibition venue that houses the largest number of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works. The artist’s most famous paintings can be seen here: Breakfast on the Grass (1863), Olympia (1863), Portrait of Émile Zola (1868), and The Balcony (1868).

Manet’s first known work, The Absinthe Drinker (1859), on the other hand, is in Copenhagen in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Other paintings by Manet are located in Europe between Mannheim (one of the versions of The Execution of Emperor Maximilian is in the Kunsthalle), Munich(Breakfast in the Atelier, 1868, in the Neue Pinakothek), Bremen, Hamburg, Zurich, Tournai(Argenteuil, 1874, in the Musée des Beaux-Arts) and Lisbon. In London it is possible to see Music at the Tuileries (1862) in the National Gallery.

In addition, a number of paintings can be found in U.S. museums, including the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which houses The Spanish Guitarist (1860), Woman with Parrot (1866) and In a Boat at Argenteuil (1874). Other paintings are in Boston (Museum of Fine Arts), Washington (National Gallery of Art), Philadelphia(The Fight between Kearsarge and Alabama, 1864, in the Museum of Art), Chicago (The Art Institute).

In Italy there is only one work by Manet ( Portrait of Mr. Arnaud on Horseback, preserved at the GAM in Milan), yet over the years several exhibitions, both monographic and thematic, have been dedicated to him. The most recent and comprehensive was held in the Royal Palace in Milan in 2017, entitled “Manet and Modern Paris.”

|

| Édouard Manet, between realism and impressionism. Life, style, works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.