Domenico Ghirlandaio, life, works and style of the great Renaissance artist

Domenico Ghirlandaio (Domenico Bigordi; Florence, 1449 - 1494) was a Florentine painter who worked during the second half of the 15th century. A contemporary of artists such as Andrea del Verrocchio and Antonio del Pollaiolo, he is considered one of the leading figures of the Renaissance. His artistic work recounts the city of Lorenzo the Magnificent, conveying its atmosphere and great cultural ferment. For this reason he is attributed a kind of chronicler of the society of his time: he worked mainly in Florence, where he directed his workshop, which was also frequented by a very young Michelangelo.

The second half of the century was characterized heady intellectual climate for a painter as broad-minded as Ghirlandaio was, very attentive to detail and a lover of ancient models: the season of perspective research had just passed, the texts of the painter and architect Leon Battista Alberti were still circulating. Sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Commentarii largely reconsidered Vitruvius’s treatise on architecture, which also returned in the ideas of the theorist Filarete, along with a marked taste for the ancient. It was also a time when works of Flemish painting were circulating in Florence, making known the names of Hans Memling, Rogier Van Der Weyden and especially Hugo Van Der Goes-the latter arrived in Florence through commissions from the Baroncelli and Portinari families, agents of the Medici Bank in Bruges. Ghirlandaio was perpetually in touch with this reality, so alive and full of opportunities: he seized every stimulus from it, opening himself to the Renaissance.

Within his lifetime Ghirlandaio went to Rome twice, the second time in 1481 with the commission to fresco the middle register of the Sistine Chapel. The Roman experience was a most important moment for the painter, who was also fascinated by the rediscovery of Nero’s Domus Aurea and its pictorial decorations, later known as "grotesques." Ghirlandaio was one of those painters who experienced the rediscovery by lowering himself into the open tunnels on the Colle Oppio and leaving his signature on the walls of the domus. Beginning in the 1970s, the artist enjoyed great success and was much in demand among Florentine high society, not least because of his distinct gifts as a portrait painter. The care, the elegance he placed in detail were tangents that led scholars several times to investigate his relationship with Flemish art.

In addition to Ghirlandaio’s boundless passion for antiquity, the raison d’être of his pictorial activity was essentially to document and communicate the culture and customs of his own time, a power of witness that his works still exert today.

Life of Domenico Ghirlandaio

Domenico Bigordi, born in Florence in 1449, was the first of five children of the goldsmith Tommaso del Ghirlandaio. From these comes the name by which he is considered one of the most celebrated painters of the Renaissance: his father, in fact, was the inventor of “garlands,” splendid hairstyles in vogue among Florentine maidens and noblewomen. Initially, Tommaso del Ghirlandaio directed Domenico to the art of goldsmithing: but the latter, “not liking that, did not remain continually to draw” since “he was by nature made to be a painter” (Vasari). In the Lives, Giorgio Vasari provides complete news about the painter: he relates that the young Ghirlandaio found his first master in the painter Alessio Baldovinetti, who had the merit of introducing him to Flemish art when it began to spread in Florentine circles.

Ghirlandaio worked mainly in Florence, but he went even further: still in Tuscany, in 1475 he frescoed the Stories of Santa Fina in the Collegiate Church of San Gimignano. His artistic activity also took him to Umbria, to Narni, but wherever he went his works clearly stood out for their consideration and rendering of his own time combined with a studied re-proposition of iconographies and models from antiquity.

A passion for the antique, Ghirlandaio cultivated it not only in Florence but also in Rome, where an early trip in 1475 with his brother David is documented. Here the artist must have been thunderstruck by the Eternal City and its ruins: during his stay, the painter participated in the rediscovery of the rooms of the Domus Aurea and its decorative systems. As many other painters did, he too left his signature on the walls - to be precise in room 129, known as Hector and Andromache. Domenico Bigordi signed himself to testify to his involvement, as he also did with his painting, aimed at restoring this classical fervor, a love that continued throughout his career. In Florence the master established his workshop, in which the very young Michelangelo also worked.

The end of the 15th century was a prosperous time of great cultural dynamism, fostered in part by the political peace between Florence and Rome. Proof of this remains the exchange between Pope Sixtus IV and Lorenzo de’ Medici: in 1481, at the pontiff’s request, the Magnificò sent the best artists to decorate the Sistine Chapel. Among them were Pietro Perugino, Sandro Botticelli, and Cosimo Rosselli, with their assistants and helpers. Ghirlandaio left with the team and also brought with him Michelangelo, whose young hand has been much sought after among the Sistine frescoes, without ever actually being identified. At that time, moreover, the hierarchical relationship in the workshop was very well structured and it was difficult for the leadership of a composition to be left to a hand other than that of the workshop leader. Ghirlandaio was entrusted here with two of the Stories of Christ.

During the 1480s, the master continued to work in Florence, where he worked in the church of Santa Trinita for the Sassetti family. Later, in 1486, Giovanni Tornabuoni (already portrayed in the Sistine Chapel frescoes) approached Ghirlandaio to fresco the family chapel in Santa Maria Novella. He was a man of great culture, much more powerful than the Sassetti family, as well as very close to the Medici, since his sister Lucrezia had married Piero de’ Medici. Ghirlandaio frescoed for him the Stories of the Virgin and St. John the Baptist. Also for the latter family, a few years later he also painted the famous portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni: after all, the painter had become the most sought-after portrait painter in Medici Florence, and he had no challengers in this artistic sphere. Regarding these talents, Giorgio Vasari relates an anecdote from his childhood: “being endowed by nature with a perfect spirit and admirable and judicious taste in painting, though a goldsmith in his boyhood he was, always attending to drawing, he came so ready and early and easy, that many say that while he dwelt at the goldsmith’s, portraying every person who passed by the workshop, he immediately made them resemble him: as is still testified to in his works by infinite portraits, which are of most vivid similitudes.”

Ghirlandaio devoted himself to the production of altarpieces, again in the Florentine sphere. The last panels show traces of the intervention of different hands, since Ghirlandaio had by then achieved a certain fame and was forced to turn to the help of assistants and friends. Two of his brothers were good painters, David and Benedetto, and his brother-in-law Bastiano Mainardi, a painter from San Gimignano, also worked for him. In these works on panel, the master’s contribution becomes progressively less and less identifiable. In 1494 Domenico Ghirlandaio died in Florence, at the age of 44. He was mourned by his assistants, his son Ridolfo, also a notable painter, and other excellent artists who were still inspired by his works, “Onde per tal ricchezza e memoria, nell’arte merita grado et onore, et essere celebrato con lode straordinarie dopo la morte” (Giorgio Vasari).

Ghirlandaio’s style and main works, between ancient and modern

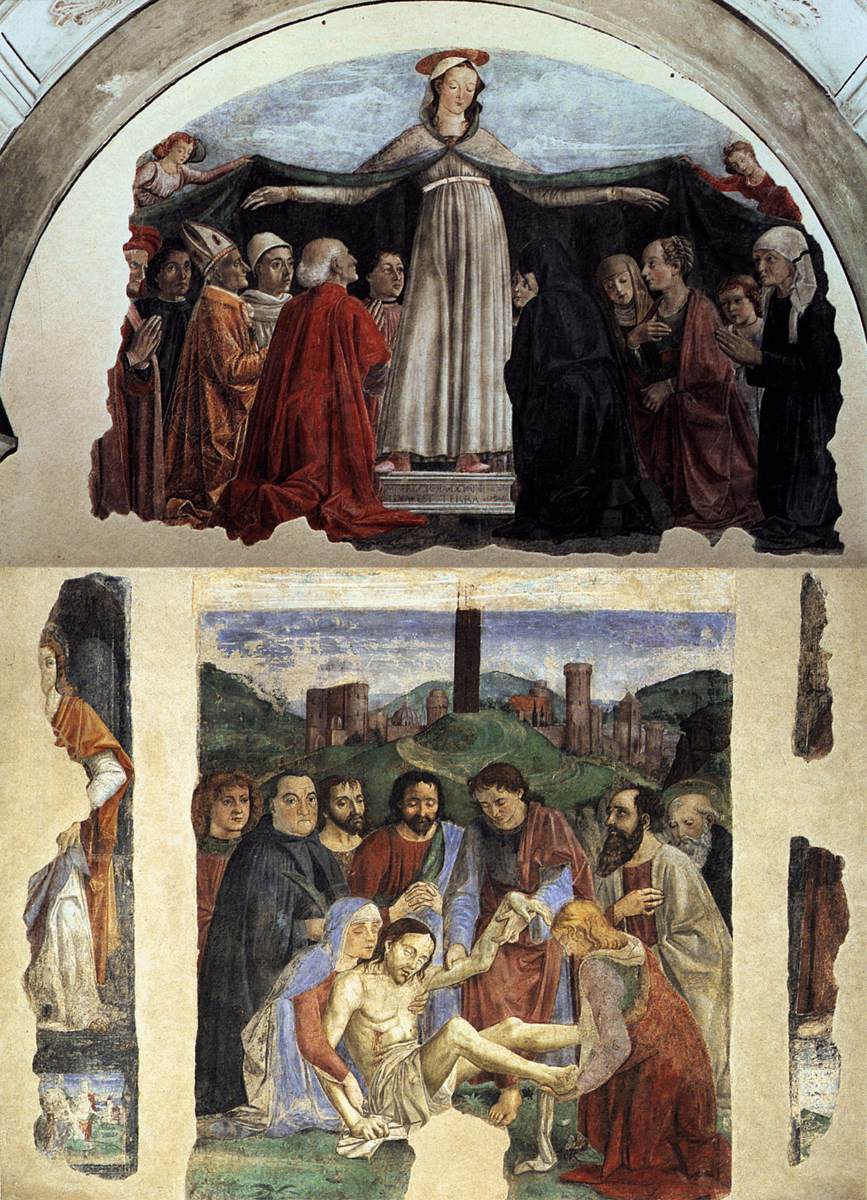

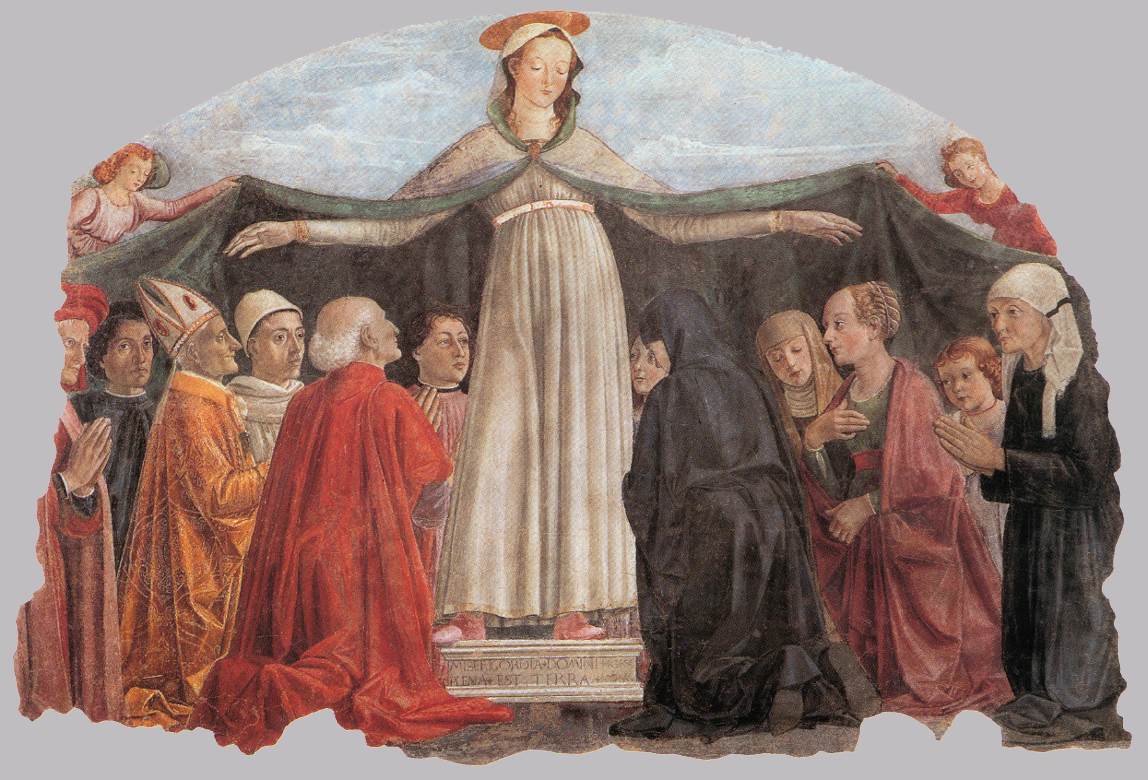

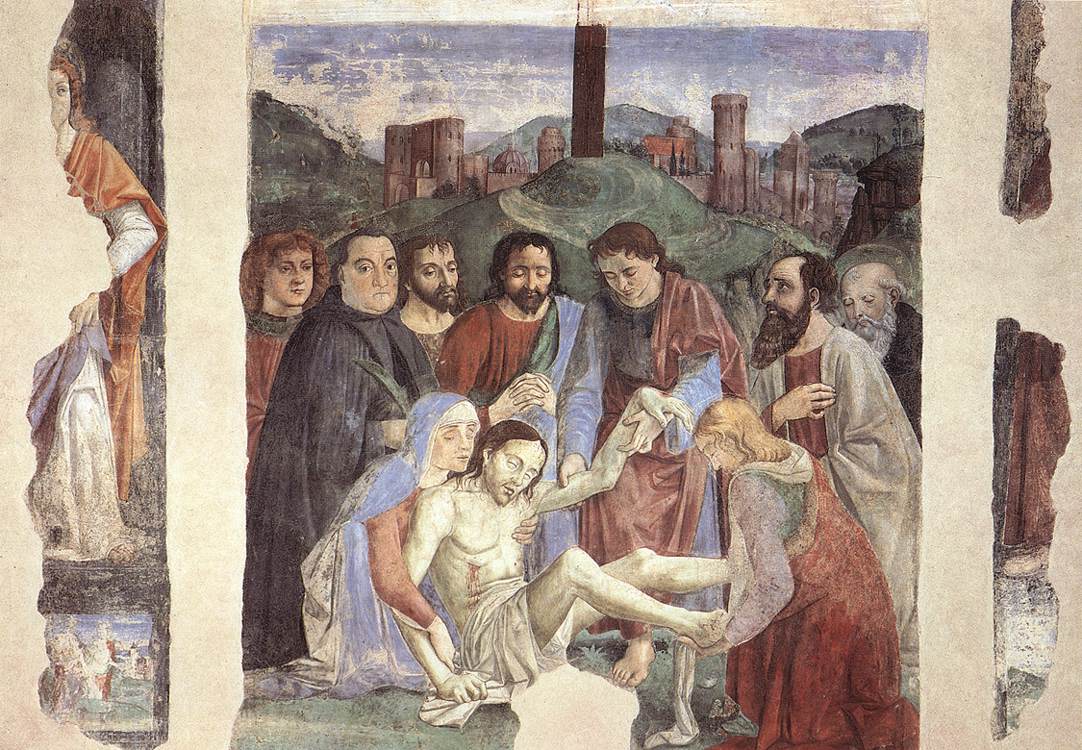

Domenico Ghirlandaio began working in country churches in the immediate vicinity of Florence: his first known work is the fresco decoration in the church of Cercina. Saints Jerome, Barbara, and Anthony Abbot are portrayed lodged in mock pilaster architecture with Corinthian capitals. The longilinear figures are rendered with softness and restore harmony through the choice of vivid colors and the fluidity of lines. In this early Ghirlandaio is suggested an early search for movement of the masses, but without breaking out into great dramatic force. At the height of 1472, Ghirlandaio was in the service of the Vespucci family, a famous noble family allied with the Medici. For them he frescoed the chapel in the Church of Ognissanti. In the central panel appears the Pieta . At the top, above the arch, appears the Madonna of Mercy opening her mantle in an act of protection: below this are the various figures of the commissioning family, where Ghirlandaio demonstrates the attention to physical detail that confirmed him in his qualities as a portrait painter.

Later, in 1475, Ghirlandaio frescoed the Stories of Santa Fina in the Collegiate Church of San Gimignano. It was in works such as these that the painter defined his artistic scope, focusing on a flat disclosure that could reach everyone. In theApparition of Saint Gregory, the perspective construction in the interior architecture is highlighted, the calm tone of the figuration, with its slow rhythm; the compositional scheme has no great pretensions, but is transparent and essential. In the Esequie di Santa Fina one can follow Ghirlandaio’s interest in antiquity, which was purely that of the plastic world, a marble antiquity, that of Roman ruins and ancient numismatics: in this regard, it should be remembered that the most important numismatic collection of the time was precisely that of Lorenzo de’ Medici, who contributed largely to the spread of this interest.

The first trip to Rome around 1475 must have been of great satisfaction to the painter. He went there for the fresco decoration of the Vatican library, together with his brother David. The frescoes in question are lost, but the trip is documented. “He was described as a grand draughtsman and a great lover of antiquities: they say that in portraying antiquities of Rome, arches, baths, columns, coliseums, needles, amphitheatres et aquiducts, he was so fair in drawing that he did them by eye, without ruler or sixths and measures; and measuring them by then made that he had it, they were as fair as if he had measured them. And portraying the Coliseum with the eye, he made a figure standing upright on it, which by measuring that the whole building was measured; and having made experience of it by the masters after his death, he found himself most just” (Vasari). In 1481 his second stay in Rome took place, where he was called by Pope Sixtus IV to paint the frescoes of the middle band of the Sistine Chapel.

Here, the scene of the Vocation of the First Apostles is very much related to Florentine painting. The figures are simple, statuesque and columnar, and the echo of the Masaccio lesson can still be felt. On the right, the small group of women talking reveals the painter’s worldly spirit, and it is clear how well inserted he was in the dynamics of Florentine society, as still evidenced by the glances and gestures of the figures higher up, intrusive and curious about what is going on.

Back in Florence, Ghirlandaio revealed his passion for the antique in almost all his works. It was a time of clear stylistic evolution, thanks in part to his contact with and study of Flemish art: figures became more majestic, landscapes were henceforth less conventional. The fresco cycles executed in the 1480s correspond to the most important mature works. In 1485, Ghirlandaio frescoed the Sassetti Chapel with the Stories of St. Francis in the Church of Santa Trinita: famous is the scene of the Confirmation of the Rule where the artist also portrays several of his contemporaries. Also for the same environment, he made a tempera on panel painting with the scene of theAdoration of the Shepherds . The hut of the holy family is built on the model of a ruin; at the top one notices the quotation of epigraphs Classical, taken from real sarcophagi. The landscape in the background is of clear Flemish derivation. In the chapel, on either side of the altarpiece, are frescoed profiles of the patrons, Francesco Sassetti and his wife.

Between 1486 and 1490, Ghirlandaio devoted himself to the decoration of the Tornabuoni Chapel in Santa Maria Novella. On this occasion he was helped by many assistants (including Michelangelo) and painted the Stories of the Virgin and the Stories of St. John the Baptist . Here, too, the memory goes to classical sculpture; moreover, we detect a small hint of the pictorial and decorative modes seen in Nero’s Domus Aurea. While the style progressed pressured by Flemish encouragement and fueled by the continuous search for ancient iconographies, the main goal of his painting remained the same, namely that of a faithful scenic representation, where the narrative had to constitute a sincere testimony of the time. Even if the subject was religious, the symbolism had to draw from reality. For this reason, the characters frescoed for Tornabuoni dressed according to the fashion of the time, while referring to scenes from much more distant eras.

In the Nativity of the Virgin, Mary’s birth is narrated as an ordinary and collected event, but it takes place in an interior of refined and sumptuous architecture with a classical flavor, as is evident from the friezes with cherubs. The attention to detail and the desire to tell the story of Florence’s environment and society is evident in the material rendering of the characters’ clothing, but also in the gilded inlays on the walls, which refer to the applied arts then in vogue in Laurentian Florence. Another scene that helped proclaim him a leading painter of the Renaissance is that of the Visitation, one of the most important stories from an iconographic point of view.

Among panel paintings, theCoronation for Narni Cathedral testifies to his work in Umbria (1486) and, again for the Tornabuoni family, theAdoration of the Magi (1487). It should be noted that, despite the wide reception shown towards Flemish painting, Ghirlandaio continued to make his altarpieces with theuse of tempera, without following the new trend of oil painting. Finally, among the masterpieces is the profile portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni, executed in 1488, which is also the year of the girl’s death. The painting, still executed in tempera on panel, is now preserved in Madrid. The young woman-who also appears in the aforementioned scenes in the Tornabuoni Chapel-is portrayed in profile with great finesse; her hair and clothing follow the fashion of noble Florentine society. Behind the hairstyle is a necklace of red coral beads and a cartouche with an inscription and the year of the maiden’s death. The inscription is taken from an epigram by the Latin poet Martial, a quotation that testifies to the painter’s all-encompassing interest in ancient culture, not only figurative but also literary. The work is executed with immense care and reveals the fully successful encounter with Nordic art.

Where to see the works of Domenico Ghirlandaio

In Florence, the painter’s hometown, see the frescoes in the Sassetti Chapel in the church of Santa Trinita, and those in the Tornabuoni Chapel in the basilica of Santa Maria Novella. The frescoes of the Vespucci Chapel executed in the late 1970s, on the other hand, are in the Church of Ognissanti. Also in Florence, in the Uffizi Gallery, is theAdoration of the Magi (1487) and another tempera on panel painted between 1480 and 1483, the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints Dionysius the Areopagite, Dominic, Clement, Thomas Aquinas and angels . Still in Tuscany, in the Collegiate Church of San Gimignano are frescoes from 1475 with the Stories of Santa Fina. In Lucca, the Duomo di San Martino houses the panel depicting the Enthroned Child between angels and saints.

In Rome, the Sistine Chapel houses a fresco by the hand of Ghirlandaio: Vocation of the First Apostles, in the middle band. In Umbria, at the Museo Eroli in Narni is theCoronation panel, an altarpiece executed for the cathedral around 1486.

Abroad, the Musée du Louvre in Paris holds a panel with the Visitation executed in 1491. The formidable Portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni (1488) is in Madrid, at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum. Overseas, the Kress Collection in Washington houses a panel painting of the Madonna and Child (1470-1475).

|

| Domenico Ghirlandaio, life, works and style of the great Renaissance artist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.