Der Blaue Reiter. History and style of the expressionist group

Der Blaue Reiter (“The Blue Rider”) was an organization of artists founded in Munich , Germany in 1911 and active until 1914, which contributed to the establishment of abstract art. The group was one of the two fundamental nuclei ofGerman Expressionism, consisting of international artists who produced works and theories on art at the turn of the century, organizing traveling group exhibitions until World War I. Their production was mainly related to emotional and spiritual values of personal expression, the developments of which were decisive for subsequent visual experimentation throughout the twentieth century.

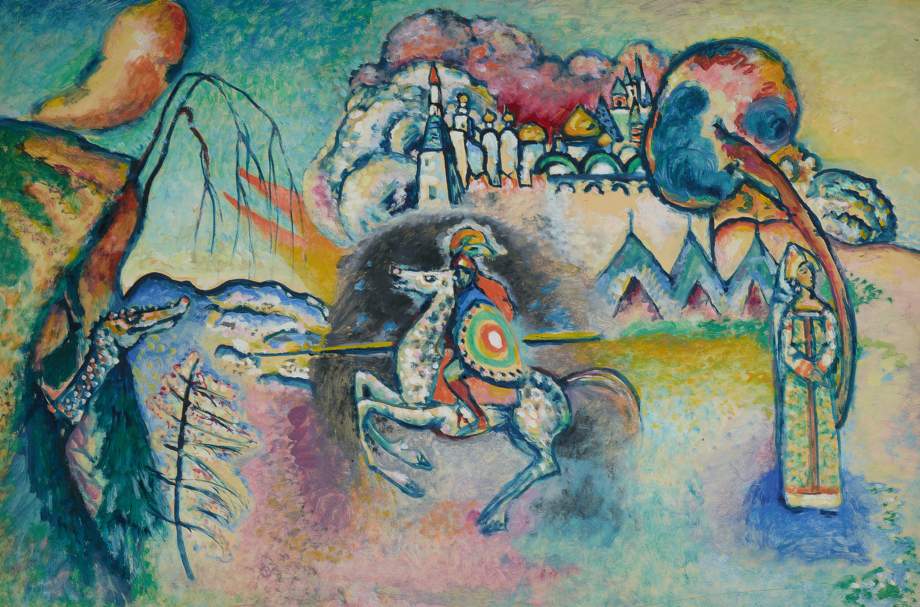

In the first decade of the century, Munich was a culturally important city, a magnet for young artists who converged there to make contact with new experiences and break new ground. Among them was Russian Vasily Kandinsky (Moscow, 1866 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1944), who abandoned a promising academic career (he had studied law) at age 30 to devote himself to painting. In 1911, Kandinsky and others, who shared intentions of innovation in artistic language, broke away from the NKvM - Neue Künstlervereinigung Mün chen (New Munich Artists’ Association) to which they belonged and founded theDer Blaue Reiter group . These painters confronted the practice of Dresden’s other expressionist group Die Brücke ( “The Bridge”), but undertook a more spiritual, anti-naturalist and anti-figurative quest. Their painting was intended to be essentially a subjective rebellion against reality and an expression of inner content through structured but non-objective representations in altered, vivid and highly significant colors.

In addition to the Russian Kandinsky, whose driving personality was oriented toward the search for rhythms of forms and colors in relation to music, the group included the Germans Franz Marc (Munich, 1880 - Verdun, 1916) who was its co-founder, Gabriele Münter (Berlin, 1877 - Murnau am Staffelsee, 1962), August Macke (Meschede, 1887 - Perthes-lès-Hurlus, 1914), the Russians Alexej von Jawlensky (Torok, 1864 - Wiesbaden, 1941) and Marianne von Werefkin (Tula, 1860 - Ascona, 1938), with, among several others, the Swiss Paul Klee (Münchenbuchsee, 1879 - Muralto, 1940). The ideas and writings of these artists helped lay the groundwork for revolutionary experimentation.

History of Der Blaue Reiter Group

In early 1909 in Munich, Russian Vasily Kandinsky had proposed forming a new group of artists to organize exhibitions free from traditional academic and exhibition dynamics. He became president of NKvM - Neue Künstlervereinigung München (New Munich Artists’ Association), which already brought together at those dates several of the future members of Der Blaue Reiter. Members included Russians Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin, as well as Germans Gabriele Münter, Alexander Kanoldt and German-American Adolf Erbsloh. Aside from their desire to break away from the dominant art establishment, these artists shared a visual style that drew on the lessons of French Fauvism and to some extent Symbolism, and that followed the experience of the pioneering German Expressionist group Die Brücke, which had been formed by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, operating in Dresden from 1905 to 1911 and in Berlin until 1913.

For the NKvM and the later formation of the Der Blaue Reiter group, the Die Brücke artists were a reference. The Munich artists, however, pursued quite different goals than their Dresden “colleagues.” Both groups found inspiration in the use of bold color from the Fauves and historical printmaking techniques such as woodcut, but while the Die Brücke artists used vibrant colors to express the heightened emotion of their simplified figures, for Kandinsky and his those colors had to go beyond mere emotional persuasion through form to find resonance in the human soul.

Der Blaue Reiter (the title was taken from a 1903 Kandinsky painting and The Blue Horses painted by Marc in ’11) was formed at Kandinsky ’s own initiative in 1911 after one of his works was excluded from an NKvM exhibition. The rejection of the painting The Last Judgment (1910) created a split among the members, which was followed by the organization of an independent exhibition also known as the “First Exhibition of the Editors of the Blue Knight.” Held in late 1911 and early 1912 at the Moderne Galerie Tannhäuser in Munich, it included more than forty works by 14 artists, for a variety of work that immediately reflected an interest in free experimentation and authentic expression. In addition to Kandinsky and Franz Marc, others included Gabriele Münter and August Macke and the experimental composer Arnold Schoenberg.

Following this, in 1912 several new associates offered to take part in a second group exhibition devoted largely to graphic art, which was held at Hans Goltz’s “New Art” Gallery, with 315 works by more than 30 international artists from Art Nouveau, Cubism and “naive” folk art. Among them were Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso, and Georges Braque. The group’s position became explicit in Der Blaue Reiter Almanach, a collection also published in 1912, edited by Kandinsky and Marc, which brought together 14 articles and theoretical essays, quite decisive for the group’s later aesthetic developments, and more than 140 reproductions of works of art.

Paintings and illustrations by such masters as El Greco, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse, Rousseau, and the Die Brücke group with Kirchner and Heckel, and clearly their group. Images compared with medieval woodcuts, carvings and tapestries, and with artifacts of Bavarian glass art, and others made outside Europe, such as bronzes from Benin to childlike drawings, for example. Thanks to the centrality of Kandinsky and Marc, Der Blaue Reiter achieved a unifying theoretical rigor that made it a more defined movement than its NKvM predecessor.

Just two years before theAlmanac came out, in 1910, Kandinsky had written the treatise The Spiritual in Art (later published in late 1911 translated from the original German into French and English) solidifying himself as a revolutionary art theorist of the time. For Kandinsky, the modern artist had a mission to lead his viewer to spiritual transcendence through his abstract or non-objective expression, built on knowledge of the work’s effect not only on the eye but on the soul, a principle he called"inner necessity." His most decisive insight was to connect the visual components of the work of art with extra-visual elements, such as emotion, thought, abstract par excellence, thus lacking tangible or figurative manifestation. In their search for a language to express their abstract approach, the artists of the group led by Kandinsky drew parallels between painting and music, often titling their works “compositions,” “improvisations,” and “studies,” drawn from musical terminology, exploring synesthesia, as an association between the senses in the perception of color, sound, and other stimuli.

Der Blaue Reiter ’s two exhibitions traveled throughout Europe from 1912 to 1914 with venues in numerous international cities, and theAlmanac was widely read during this period, further spreading the group’s ideas. Their final exhibition took place at the famous Galerie “Der Sturm” in Berlin, where their work was also included in an exhibition called the “First German Salon d’Automne,” held in 1913. But with the outbreak of World War I Der Blaue Reiter prematurely dispersed. Marc and Macke were conscripted into German military service and killed shortly thereafter, and the foreign members of the group, Kandinsky among others, were all forced to repatriate. Having escaped the war they met again: in 1924 Kandinsky, Klee together with the American Lyonel Feininger, who had become teachers at the Bauhaus in Weimar, formed with the other former member Alexej von Jawlensky a new group, Die Blaue Vier ( “The Blue Four”), exhibiting together from 1925 to 1934.

The style of the major exponents

Although the painting style varied from one artist to another within Der Blaue Reiter, the group moved toward common tendencies. Their expressionism was seen as the abstract counterpart to the distorted figurative style of Die Brücke and as a coloristic response to the contemporary monochromatic formal explorations undertaken by the Cubist avant-garde in Paris. If Picasso and Braque were simplifying their palettes to grays and browns in order to focus better on matters of form, the artists of Der Blaue Reiter intensified their use of color untethered from appearances, theorizing its symbolic qualities. This is already understood from the “blue” attribute of the knight in the name, which referred to Kandinsky and Marc’s belief that blue with its hues was the color that most symbolizes the ability to go beyond the earthly condition. They employed colors that were not naturalistic, as Die Brücke did, but with decidedly more lyrical and evocative effects, each interpreting the world with his or her own gaze, as subjective disobedience to reality.

In The Spiritual of Art and in essays published in theAlmanac, Kandinsky expounded and developed his theory of the properties of colors, for which, for example, yellow came to represent heat and excitement, signifying joy, annoyance or enervation, and the more peaceful and spiritually resonant blue could lead to a feeling of calm. Similarly, Marc also established a theory that assigned symbolic values to specific hues. For example, in his predominantly figurative woodcuts and paintings of animals in nature, yellow came to represent feminine joy, while blue represented masculinity and, as with Kandinsky, spirituality(The Yellow Cow, 1911; The Fate of Animals, 1913). Color symbolism was employed at different levels in the works of many Der Blaue Reiter artists. Among others, Klee, an experimental musician and draftsman, also initiated a revolutionary coloristic exploration at that time. Inspired by Kandinsky’s writings, he began to move beyond his early black-and-white works toward an intense study of color and abstraction that made him one of the central members of the group. The watercolor and pencil on paper In the Style of Kairouan of 1914 is considered his first entirely abstract work, in which the painter chose to forgo recognizable imagery for a balanced geometric composition of circles, rectangles and irregular polygons delicately colored in a variety of mixed hues.

These artists all also had attention to the arts of the “primitives” from Africa, Oceania, North America and the Far East, who were closer to an innate and immediate state of spirituality that civilization had lost. The innovation of their painting was in the idea that simplified colors and forms, as in authentic primitivism, led to contact with lost and transcendent archaic values. In his essay entitled “The Savages of Germany,” also published in theAlmanac, Marc described his colleagues-including the artists of the NKvM, the Berlin Secession and Die Brücke-as “savages” fighting against an “old constituted power” to create “symbols belonging to the altars of a future spiritual religion.” This rehabilitation of the notion of the “savage” went hand in hand with the rediscovery of “primitive” art that penetrated Europe collected in ethnographic museums and supplanted Eurocentric classicism.

The break with the intellectual constraints of modern Western society enabled them to achieve a “simpler” means of expression, and this meant that forms, rendered in a direct, less articulate and less verisimilitude, could move away from the canonical beauty that had previously been considered the highest goal of art, tending toward the supreme abstraction of form.

The contents of Der Blaue Reiter Almanach also demonstrated the group’s commitment to musical form, given in part by Kandinsky’s codifications of the synaesthetic relationship between color and sound. Music was the perfect analogy for abstract visual art, not only capable of evoking deep emotional responses or spiritual resonances, but, through the recognized timbres of certain instruments, able to evoke images or associations despite the inability of the human eye to “see” music. The language of sound imparted a vibrancy and power to painted compositions, which could be loud and cacophonous or quiet and harmonious; a pigmented form could grow on a canvas, or a combination of tones create a visual vibrato. The painter precisely defined his pictorial compositions as “inner visions,” similar in everything to a symphony.

Made during his time with Der Blaue Reiter, Composition VII (1913) is widely regarded as one of his greatest masterpieces (two-by-three-meter oil on canvas), presenting an ensemble of colors and forms in which images appear that are not immediately recognizable, but strongly expressive and evocative, which art critics have largely tried to interpret. The drive for abstraction by Kandinsky and others was based on the belief that humanity was living at the end of time and required a spiritual rebirth. But the widespread destruction of World War I struck many artists and intellectuals as an apocalypse.

August Macke ’s 1914 oil on cardboard Farewell reflects the mood that overwhelmed Europeans. Painted after the outbreak of World War I and the subsequent dissolution of Der Blaue Reiter, it was also the last painting Macke completed before his death at the front. The subdued, mixed palette contrasts with the brightly colored prewar canvases, and the looming alienated and anonymous bodies are visual signals of the feelings of fear and anxiety of that wartime era. The simplified, featureless figures derived from Der Blaue Reiter’s approach to abstraction, although the feeling of spiritual redemption had faded.

|

| Der Blaue Reiter. History and style of the expressionist group |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.