Dadaism. Origins, development and main exponents of the avant-garde movement

Dadaism or the Dada movement was an avant-garde artistic and literary movement with an international scope, which arose in Zurich in 1916 and spread to other countries in reaction to World War I, the artistic norms and nationalism of the time, which many believed were the cause of those tragic wartime events. Dada artists revolutionized traditional categories, techniques and modes of art enjoyment, making themselves decisive in 20th-century culture and for its evolution to the present day. The Zurich Dada experience, the result of an irreverent attitude toward the society and conventions of the time, proved highly influential on artists in several cities, including Berlin and Cologne, New York and Paris, who each generated their own Dadaist groups. The movement later disbanded between 1922 and 1924 with the establishment of Surrealism, but the ideas sparked in those few years are to this day the cornerstones of various categories of modern and contemporary artwork, from poetry to abstract photography, collage,assemblage andinstallation, to performance art and conceptual artworks.

The output of Dada artists was extremely diverse, influenced by the avant-gardes that were emerging in the early twentieth century, such as French Cubism, Italian Futurism, Russian Constructivism, and German Expressionism, completely encroaching on previous artistic standards and canons. The movement arose from a common antiwar stance among artists and the need for a free creative outlet. The very strong emotional impact of the Great War had heightened in many young people the feeling that it was necessary to demolish at any cost the “old order” of culture that had produced and justified it.

The first group was formed in Switzerland, neutral in the conflict and home to refugees of various nationalities. Among them were the Romanian poet Tristan Tzara (MoineÈ™ti, 1896 - Paris, 1963), German writers Hugo Ball (Pirmasens, 1886 - St. Abbundius, 1927) and Richard Huelsenbeck (Frankenau, Hesse, 1892 - 1974), Alsatian painter and sculptor Hans Arp (Strasbourg, 1887 - Basel, 1966) and others who met at the Cabaret Voltaire, a Zurich meeting place that hosted poetry evenings, exhibitions and acts of cultural provocation. About the founding of Dadaism, Arp said, “We were looking for an elemental art that would cure men of the madness of the age, a new order that would restore the balance between heaven and hell.” Thus new techniques were born and the infinite artistic possibilities of chance were explored. Dadaism was not a style, nor did it imply a unique and consistent way of conceiving artistic expression: the Dadaists acted in a desire to shock the public, gradually taking on a nihilistic, derisive and irreverent attitude toward traditional art. Starting with the name “dada,” which meant nothing in particular, and seems to have been found by randomly looking up a word in the Larousse dictionary. Art lost its magical aura: the works changed form and the usual passive relationship between the viewer and the finished creation also changed.

The disruptiveness of Dadaism’s cultural premises acted as a cultural enzyme, multiplying the concept of “new” and “radical” in just a few years. Once the first manifestos were launched and the first magazines published, artists of various nationalities identified with Dada approaches. All the way to New York, where Marcel Duchamp (Blainville-Crevon, 1887 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1968), Francis Picabia (Paris, 1879 - 1953) and a small group of iconoclastic renovators realized that their works fit perfectly into the new "ism." The movement took root with particular force in Germany in the years immediately following the end of the war. The country had been defeated, and in general, the German Dadaists engaged in an attempt to make the social-political revolution triumph in the country. Their creative exuberance acquired, especially in Berlin, a propaganda aspect. The crisis and end of that widespread experience ripened in Paris, where many of the adherents eventually converged. The most energetic faction, led by André Breton (Tinchebray, 1896 - Paris, 1966), launched the first manifesto of Surrealism in 1924 and thus replaced the Dada revolution with a new movement.

![Marcel Duchamp, Ruota di bicicletta (1913 [1951]; ruota di metallo montata su sgabello di legno dipinto, 51 x 25 x 16 cm; New York, MoMA) Marcel Duchamp, Ruota di bicicletta (1913 [1951]; ruota di metallo montata su sgabello di legno dipinto, 51 x 25 x 16 cm; New York, MoMA)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2022/fn/marcel-duchamp-ruota-di-bicicletta.jpg)

![Marcel Duchamp, Scolabottiglie (1914 [1959]; ferro, 59,1 x 36,8 cm; Chicago, Art Institute) Marcel Duchamp, Scolabottiglie (1914 [1959]; ferro, 59,1 x 36,8 cm; Chicago, Art Institute)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2023/fn/marcel-duchamp-scolabottiglie.jpg)

Origins and development of Dada groups

Officially, Dadaism was born by those young refugees in Switzerland, already mentioned, some of whom had founded, in Zurich, in 1916, a Cabaret which was given the significant name of Voltaire, after the French Enlightenment philosopher who championed reason against all prejudice. Along with the Romanian poet Tristan Tzara, the philosopher and writer Hugo Ball, who had fled Germany so as not to be forced to go to war, like compatriots Richard Hülsenbeck and Hans Richter (Berlin, 1888 - Locarno, 1976), who joined the group along with the Alsatian sculptor Hans Arp, who had arrived in Switzerland by chance, and the Romanian painter Marcel Janco (Bucharest, 1895 - Tel Aviv, 1984), who had stayed with Tzara in Switzerland because he was surprised by Romania’s declaration of war.

Founders Ball and Emmy Hennings (Flensburg, 1885 - Sorengo, 1948) opened Cabaret Voltaire on Feb. 5, 1916, in the back of a tavern on Spiegelgasse in a desolate part of town. Although not organized politically, they were young and opposed to the war, founding this entertainment venue for the purpose of gathering, earning and engaging their intellectual energies. To attract other artists, Ball had circulated a notice that read, "Cabaret Voltaire. Under this name a group of young artists and writers was formed with the goal of becoming a center of artistic entertainment. In principle, the Cabaret will be run by artists; guest artists will come and give musical performances and readings during the daily meetings. Young Zurich artists, whatever their tendencies, are invited to bring suggestions and contributions of all kinds."

From the first performances in July 1916 the ironic, desecrating, provocative attitude recognized as Dada gradually grew. Because the movement rejected the traditional meanings attributed to words and universally accepted concepts, they chose to call themselves by an expression that in itself is not meant to mean anything specific. This is why many narratives arose, each different from the other, about the precise origin of the name: Hans Arp said that the first to use it was Tzara, arousing enormous enthusiasm in everyone, partly because of the fact that “dada” could mean the same (or nothing) in all languages, since the group was avowedly internationalist. Tzara in turn narrated that he found the word at random in the French Larousse dictionary. “Dada” is a French colloquial term that can refer to a workhorse, but it also alludes to the first syllables a child learns to say, and these suggestions of infantilism and absurdity ensured a departure from the conventional sobriety of bourgeois language.

Dadaism immediately manifested itself as a free organization, which without a definite aesthetic program became a way of conceiving reality and the work of art. It was not interested in the artistic value of an artifact, but rather in the shock caused in the viewer, which was necessary to divert him from lazy mental habits. Art, as it had always been considered, no longer existed for them, and everything could become art: pieces of raw wood nailed and colored, for example, as in Arp’s 1920 Trousse d’un Da, or an ordinary object put in a certain position instead of another. “Freedom: DADA DADA DADA,” Tzara wrote in 1918 in rewriting their Manifesto (1916), “scream of contracted colors, tangle of opposites and all contradictions, of the grotesque and incongruity: life.” Their anti-authoritarian stance helped determine a movement without a guiding ideology.

The spread of Dada occurred from 1917 through the seven publications of an art and literature magazine entitled, of course, “Dada” and numerous art exhibitions, focusing on performance and typographic art. Just in 1917, after Ball left for Bern to pursue journalism, Tzara founded the Galerie Dada on Bahnhofstrasse, where other evenings and other numerous exhibitions were held. Tzara became the movement’s motivator and began a relentless campaign to spread its ideas, flooding international writers and artists with letters of invitation. When the war ended in 1918, many of the artists returned to their home countries, helping to further spread the Dada spirit elsewhere. The end of Dada in Zurich followed an April 1919 event that turned into an audience revolt, over a hundred people who, heated by the themes discussed at that meeting, lost control and began destroying many of the props: something that Tzara thought furthered their goals, undermining conventional art practices precisely through the audience’s involvement and emotionality in artistic production, and he described the incident thus, "[...] Dada succeeded in establishing the circuit of absolute unconsciousness in the audience, which forgot the frontiers of the education of prejudice, experienced the emotion of the New. Dada’s final victory." Participants were no longer just spectators, and this involved a total negation of traditional forms.

The spread of Dada touched various European cities and New York, attributed to a few key artists moving and mixing. Tzara moved to Paris, where he met André Breton with whom he began to formulate the theories that would lead to Surrealism. From Zurich, Huelsenbeck founded the Dada Club in Berlin, active from 1918 to 1923, which involved participants such as Johannes Baader (Stuttgart, 1875 - Adldorf, 1955), George Grosz (Berlin, 1893 -1959), Hannah Höch (Gotha, 1889 - West Berlin, 1978) and Raoul Hausmann (Vienna, 1886 - Limoges, 1971), Kurt Schwitters (Hanover, 1887 - Kendal, 1948). The Berlin Dadaists took a public stand against the Weimar Republic (1919-1933), and their art took a more political vein: satirical paintings and collages that presented wartime images, with figures of political figures recontextualized in pungent scenes. In February 1918, Huelsenbeck gave his first Dada talk in Berlin, and several magazines were published that year, along with a manifesto, including “Club Dada” and “Der Dada.” Then in 1920, Hausmann and Huelsenbeck held a lecture tour in Dresden, Hamburg, Leipzig and Prague, and in June the “Erste Internationale Dada-Messe,” the first international Dada fair. During this period, the technique ofphotomontage was developed from Berlin.

In the meantime, Kurt Schwitters, who had been excluded from the Berlin group, formed his other Dada group in Hanover in 1919, less politically oriented than the Berlin Club, but nonetheless driven by the modernist questions that were being discussed about the role of form and color in artistic images. Ideas spread through the publication of the magazine “Merz,” which came out sporadically for several years (from 1923 until 1932). Another group formed in Cologne in 1918 on the initiative of Hans Arp, Max Ernst (Brühl, 1891 - Paris, 1976) and Johannes Theodor Baargeld (Szczecin, 1892 - Chamonix, 1927). Their exhibitions focused on anti-bourgeois and, as it were, nonsensical art. In 1920, one of them was closed by the police. But by 1922, German Dada was on its last legs. In that year Ernst left Cologne for Paris, thus disbanding that group. Others became interested in other movements. A “Congress of the Constructivists,” for example, was held in Weimar in October 1922, attended by many German Dadaists; just as in 1924 Breton published the Surrealist manifesto, after which many of the remaining Dadaists joined that new movement, just like Ernst.

After hearing about the happenings of Dada in Zurich, a number of Parisian artists including Breton, precisely, Louis Aragon (Paris, 1897 - 1982), Paul Eluard (Saint-Denis, 1895 - Charenton-le-Pont, 1952) and others became interested. In 1919 Tzara had left Zurich for Paris and Hans Arp arrived there from Cologne the following year; a “Dada festival” took place in May 1920, after others from the movement had also gathered there. Numerous events, exhibitions and performances were organized, along with the publication of posters and magazines, including “Dada” and “Le Cannibale.”

Marcel Duchamp served as the crucial creative link then between the Zurich Dadaists and the Parisian proto-surrealists, such as Breton. The Swiss group regarded Duchamp’s works as Dada works and appreciated his humor and refusal to define art. Like Zurich during the war, New York City was a refuge for writers and artists. We normally date the emergence of Dadaism in New York around 1915, but an earlier event allows us to anticipate its birth even further: the Armory Show, the first vast fair that brought the art of the European avant-gardes to America, held in 1913 in an old armory and destined to fertilize New York’s artistic atmosphere.

Duchamp and Francis Picabia, who had been part of the Zurich and Paris groups, arrived in the city within days of each other in June 1915 and soon after met Man Ray (Philadelphia, 1890 - Paris, 1976). Duchamp was a critical interlocutor within the American group, already two years earlier in 1913 he had christened the word "ready-made" to refer to his particular composition of a kitchen stool with a bicycle wheel, taken from the everyday environment to be placed in the exhibition context without any manipulation by the artist. But he began making one of his most important pieces that very year in New York, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, better known as The Big Glass, now considered a milestone in contemporary art for its depiction of a strange erotic drama through mechanical forms.

In 1916 the three were joined by other artists and women artists, and much of their activity took place in the 291 gallery run by Alfred Stieglitz, a pioneer of modern photography in part through the magazine he edited “Camera Work,” and in the studio of Walter and Louise Arensberg. Their publications, such as “The Blind Man,” “Rongwrong” and “New York Dada,” challenged conventional museum art with more humor and less bitterness than the European groups. It was during this period that Duchamp exhibited objects such as his famous Bottle Rack, and with the Society of Independent Artists at an exhibition in 1917 he presented his scandalous Fountain, the upside-down urinal that changed the course of Western art history.

During these years Picabia’s frequent travels from one country to another had helped link Dadaist groups. From 1917 to 1924 he published his periodical 391 modeled on Stieglitz’s periodical 291, first in Barcelona, then in various cities including New York, Zurich and Paris, depending on his own place of residence and with the help of fellow artists and friends in the various cities. Picabia and Breton withdrew from the movement in 1921, and Picabia himself published a special issue of 391 in which he stated: “The Dada spirit really existed only between 1913 and 1918.... Dada, wanting to prolong it, came to an end.... Dada, you see, was not serious... and if certain people now take it seriously, it is because it is dead! One must be nomadic, go through ideas as one goes through towns and cities,” he wrote. Paris Dada published a counterattack under Tzara’s direction. Two last theatrical performances were held in the French capital in 1923, before the group encroached on internal struggles and succumbed to Surrealism. In the last issue of 391 in 1924 Picabia also accused Surrealism, founded that year, of being an invented movement, writing that “artificial eggs do not make chickens.”

![Marcel Duchamp, Fontana (1917 [1964]; terracotta bianca ricoperta di smalto e vernice, 63 x 48 x 35 cm; Parigi, Centre Pompidou) Marcel Duchamp, Fontana (1917 [1964]; terracotta bianca ricoperta di smalto e vernice, 63 x 48 x 35 cm; Parigi, Centre Pompidou)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2022/fn/duchamp-fontain-pompidou.jpg)

The style of the major exponents

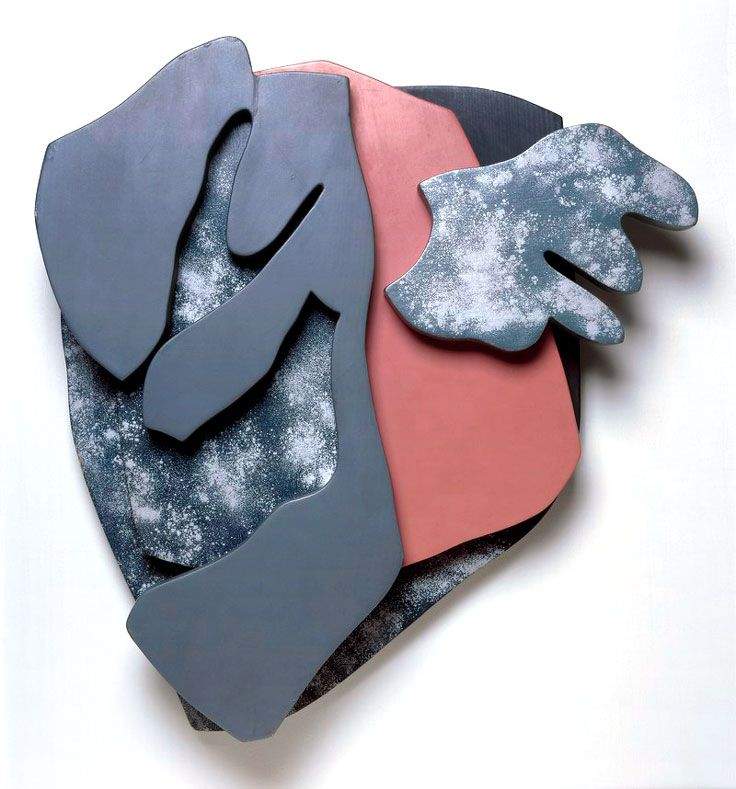

Dadaism did not manifest itself in an artistic language, proper, encompassing from the ironic machines of Francis Picabia, to the photographs called “Rayograms” of Man Ray, to the collages of Hans Arp, to the assemblages of Kurt Schwitters via abstract poetry, constructions and montages... cinema, dance and much more. Dada was the direct antecedent of the conceptual art movement, in which the artists’ focus was no longer on creating aesthetically accepted objects, but on making works that disrupted bourgeois sensibilities and generated difficult questions about society, the role of the artist and the purpose of art.

The members of Dada were so intent on opposing all the norms of bourgeois culture that the group was barely in favor of itself:"Dada is anti-Dada," they often shouted. Irreverence was a crucial component of Dada art, whether it was a disrespect for convention, authority, conventional methods of production, or the artistic canon, and each group varied slightly in its focus. The Dadaists extolled the principle of randomness, in written and spoken language and in the visual arts, because they saw it as the best defense against the conventions and rationalistic attitude they challenged. The example provided by Tristan Tzara, a proponent of the movement’s manifestos, paved the way for much experimentation, since he once explained how to compose a Dadaist poem: “One must take a newspaper article, cut out all the words and put them in a bag; then they are drawn out one by one, at random, and joined together in order of output.”

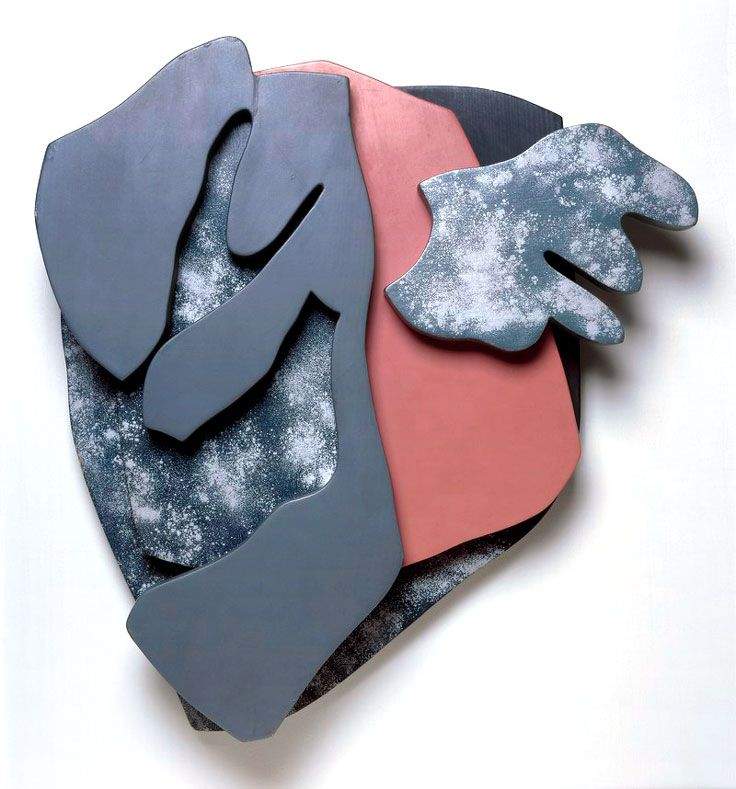

The German artist Hans Arp argued the vital importance of having recourse to the “law of chance,” which contains within itself all other laws, and was in fact the first to transpose into a painting the random arrangement of a few pieces of shredded paper, dropped on the floor. No rules or figurative reference presided over the genesis of the work, but the result was rich in poetic enchantment. To his polychrome wood reliefs he gave surprising titles, such as The Funeral of Birds and Butterflies (portrait to Tristan Tzara), executed around 1916-17.

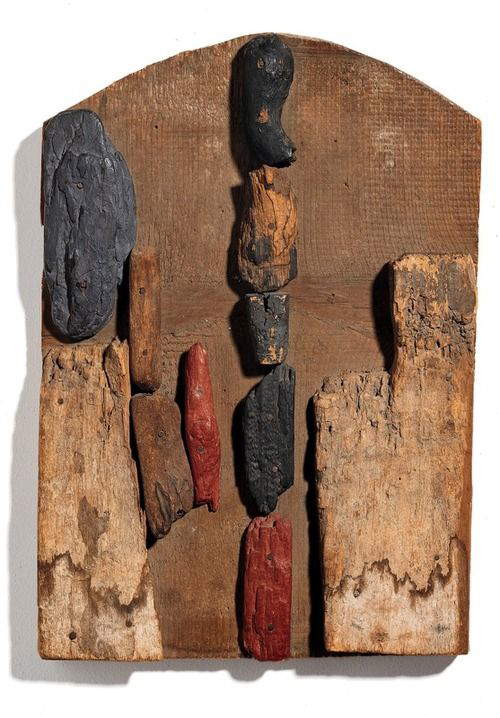

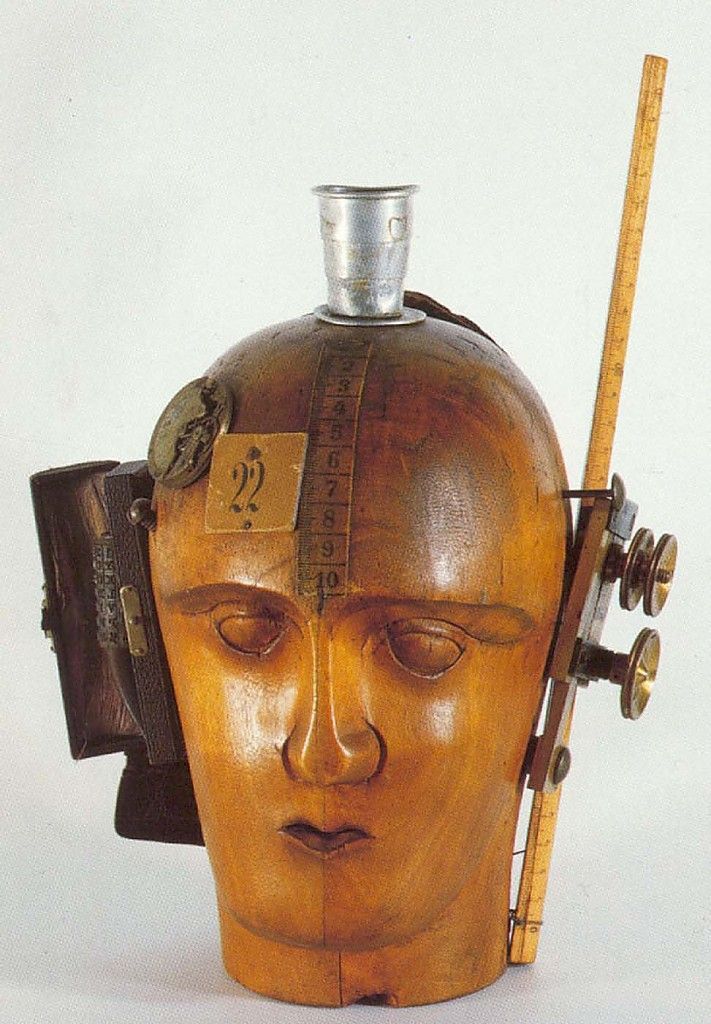

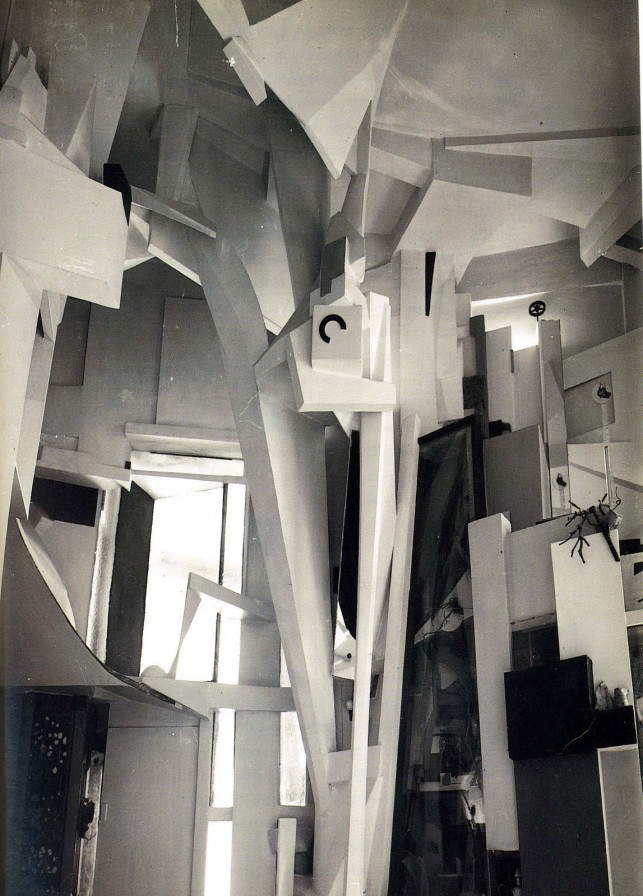

Without ever losing sight of the artistic researches developed in other countries, a practical and theoretical inclination for montages had arisen, primarily photographic montages of clippings from different sources alongside passages of text. Procedure transferred to sculpture as well. It was clear to the Dadaists that they intended to use the mechanical objects of the contemporary world ironically. One of the earliest examples is The Spirit of Our Time, a mechanical head assembled by Raoul Hausmann in 1919: seemingly completely incongruous elements were added to the wooden sculpture, such as a ruler, a piece of tape measure, brass wheels, and more. The sculpture was not modeled or carved as had always been done, but built from existing elements, “assembled as one would do with a machine” precisely. The key concept behind most of their art, from the compositions and assemblages of Kurt Schwitters to those of Duchamp, was to free creativity from logical and rational control. This went against all academic norms whereby a work was meticulously planned and then completed, questioning the artist’s role in the artistic process. Famous among Schwitters’ works is Merzbau, an extraordinary three-dimensional collage that the artist constructed in his home over time (from 1923 to 1936), filling it with disparate elements and mysterious voids: art passed all conventional boundaries by completely invading living space, blurring with the creator’s own biography.

Dada artworks presented intriguing overlaps and paradoxes, intended as deconstructions of everyday experience in stimulating and rebellious ways, such that the viewer could interpret them in various ways. This formal revolution manifested itself even more decisively with the introduction of the ready-made, which forced questions about artistic creativity and the very definition of art and its purpose in society. Duchamp was the first artist to use and name this category of works composed of already made objects, only taken from everyday life and decontextualized. The artist’s work, thus understood, no longer consisted in ’making,’ but in ’recognizing’ something symbolic that already exists. Similarly, photography was a favorite medium of Dadaism. Other artists who worked with ready-made and bizarre assemblages were Ernst, Hausmann and Man Ray, a quality, extravagance, that made it easy for the group to eventually merge with Surrealism. Decisive to their work was the use of witty, ambiguous and outrageous, irony.

|

| Dadaism. Origins, development and main exponents of the avant-garde movement |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.