Constructivism was an avant-garde movement that developed in Russia in the ideological and cultural context of the years around the 1917 Revolution and together with Suprematism constitutes one of the two main Soviet artistic currents of the early 20th century.

Placed in Abstractionism, the beginning of the movement coincides with the artistic activity of Vladimir Tatlin (Kharkiv, 1885 - Moscow, 1953), who can be considered the highest representative of the nascent Russian Constructivism on the eve of the Bolshevik Revolution: in 1913, with his “pictorial reliefs,” abstract geometric constructions made of different materials such as wood, metal, and cardboard, he initiated a conception of art untethered from representation, which developed in the space and context of the real world. An evolution of painting, sculpture and architecture together, representing the needs of the new social class of the proletariat and culture on a socialist basis, surpassing not only the bourgeois canons of nineteenth-century art but enacting an aesthetic change, in step with that of the increasingly industrialized and fast-paced society. As happened with other avant-garde movements and “isms” of the twentieth century, the progressive and unstoppable use of technologies in industrial production was interpreted by art forms. Constructivism combined aesthetics, functionality and utility and expressed itself radically through the graphic arts, experimental photography and design, and beyond the visual arts, through literature, music, theater, particularly set design, and film, influencing later developments throughout the 20th century.

Besides Tatlin, other constructivist artists were Naum Gabo (Naum Pevsner; Bryansk, 1890 - Waterbury, 1977) and Anton Pevsner (Orël, 1886 - Paris, 1962), Aleksandr RodÄenko (St. Petersburg, 1891 - Moscow, 1956) and Varvara Stepanova (Kazan, 1894 - Moscow, 1958), El Lissitzky (PoÄinok, 1890 - Moscow, 1941) and László Moholy-Nagy (Bácsborsód, Bacs-Kiskun, 1895 - Chicago, 1946), along with a large group of artists organized in the "LEF" (Left Front of the Arts), including the poet Vladimir Majakovsky (Bagdati, 1893 - Moscow, 1930), active in the movement until the 1930s.

The Constructivist movement is generally believed to have taken hold in 1913 with the “pictorial reliefs” of Vladimir Tatlin, who, after learning about geometric decomposition in the painting of the revolutionary postimpressionist Paul Céfangs, through his works seen in Russian collections and, above all, after being impressed, on a trip to Paris that year, by Cubism and Picasso’s polymateric collages, began to compose his reliefs, thus favoring the three-dimensionality of form. The actual origin of the name “constructivism” is disputed, but it certainly referred to his, and later other artists’, approach to art centered on the physicality of the work placed in space, and on construction through new, unusual materials never before used in Soviet art. The Constructivists developed a new way of conceiving expression as a union between artistic forms, beginning with the non-figurative positions introduced in the same 1913 by Kazimir MaleviÄ’s Suprematism, the first artistic movement to promote pure geometric abstraction.

Tatlin and MaleviÄ, both departing from “Cubofuturism,” a distinctly Soviet movement derived from Cubism and Futurism, exhibited their work together between late 1915 and 1916 at The Last Futurist Painting Exhibition 0.10 at the DobyÄina Gallery in St. Petersburg. MaleviÄ’s disruptive paintings were composed of geometric shapes and basic colors floating on the background; Tatlin’s reliefs, constructed mainly of metal and wood, constituted “a new kind of object” somewhere between sculpture and architecture. Traditional art, Russian as well as European, was thus completely outmoded. The ideal assumptions of Constructivism rejected bourgeois art, identifying in the new social-political context of the Bolshevik revolution the real possibility of building equally revolutionary art.

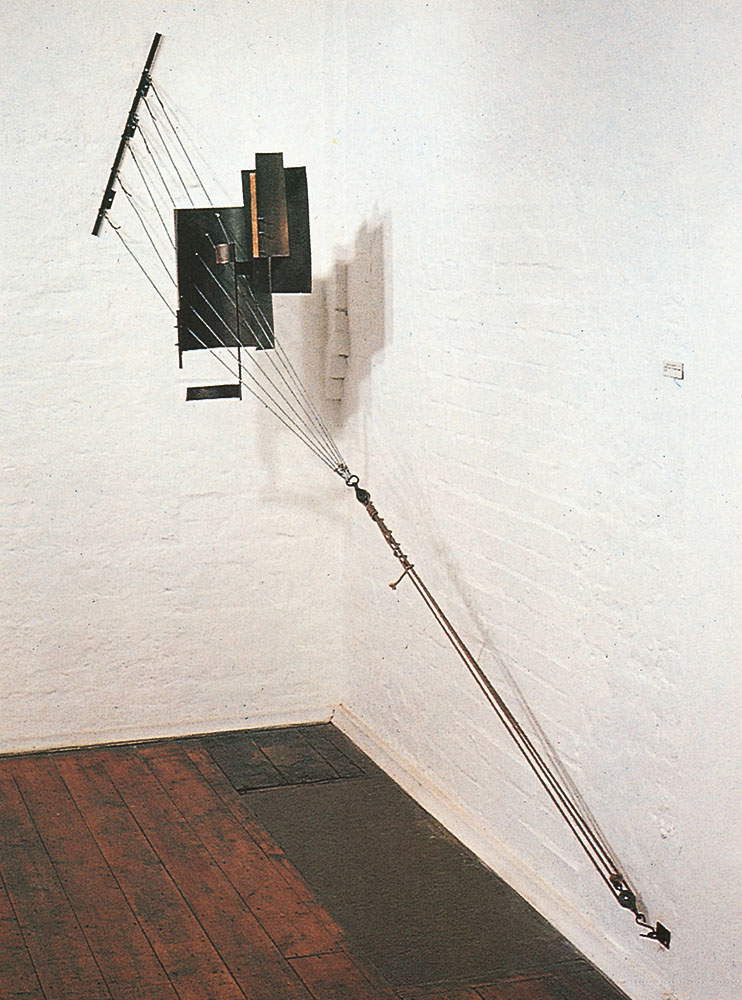

On the social impetus, Tatlin determined Constructivism from Suprematism but with the goal that the art object had a function. In the sense that art was conceived as functional, constructive, attentive to the new industrial materials and techniques of the time, no longer elitist and academic, and that it could bring us closer to the working class, the people of the revolution. In 1915-16 date his innovative works such as Angular Constructions or Counter-reliefs.

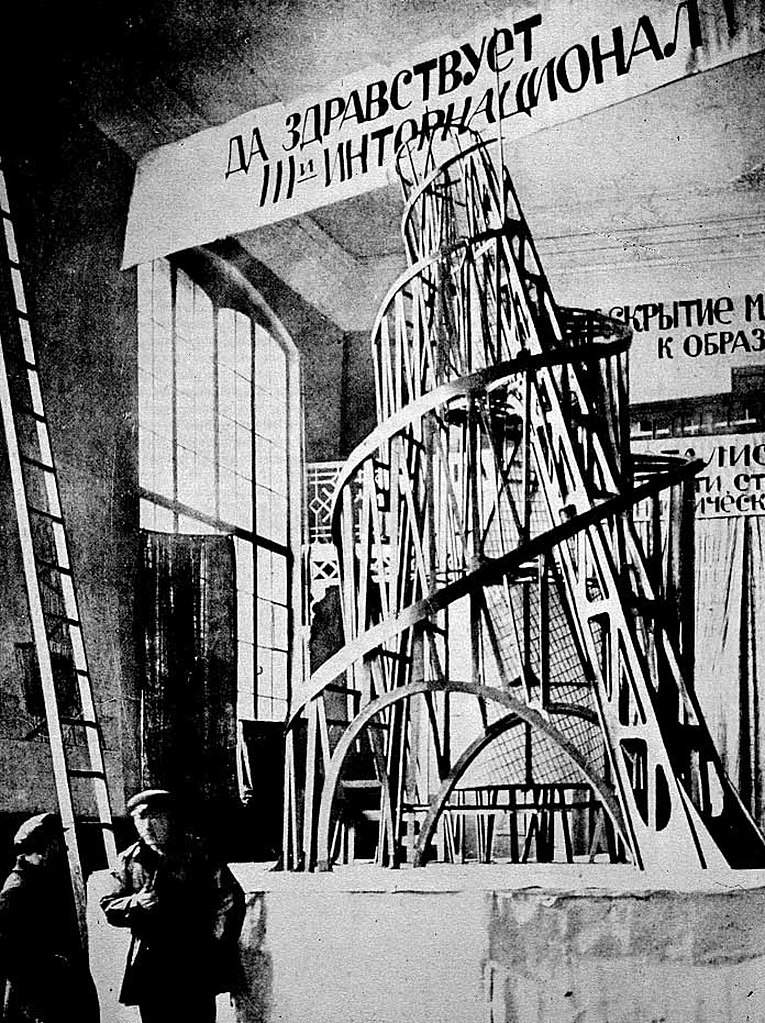

Then in 1919 Tatlin designed his most important work: the famous Monument to the Third International (a model of which was exhibited in 1920 but never built), a grandiose metal trellis set on diagonal axes and a spiral, with a dynamic thrust from the bottom to the top. An abstract but symbolic composition, of the conquering march of socialism, and at the same time functional, because it provided three overlapping rooms intended for social-political purposes. A gigantic structure that would commemorate a momentous turning point in Soviet history, the “Third International,” founded by Lenin in 1919 with the aim of leading to world communist revolution. The Monument, which was to have been the tallest building in the Soviet world, 400 meters in height, could not be built, but a strikingly sized model of it was nonetheless made, 25 meters in height, a synthesis, as they said, of symbolic expressiveness and functionality.

For the figurative arts, the communicative aspect of art took hold in the movement, starting witharchitecture and sculpture, and including graphic design and typography, for posters, pamphlets and magazines, and design, everyday objects and textiles, put back into the service of the people. But there were many overlaps among the Constructivist art forms, as not all of Tatlin’s artist followers accepted thefunctional element of art dictated by his designs and sculptures.

Within Constructivism, several souls were soon distinguished. For Tatlin, art as an end in itself was to be condemned as a product of capitalist society: the only task incumbent on the artist was to “construct” an art in the service of the masses through his engagement in such fields as precisely architecture and sculpture, graphic design and industrial production. In contrast, a different position was taken by the two brothers Naum Gabo and Anton Pevsner , who in 1920 published the Realist Manifesto (of Constructivism) in Moscow to distance themselves from the strongly ideological approach given by its founder. Art for them was not to be useful to man in society per se, but to help him establish contact with the deep essence of reality and the structures that support it. Abstract structures that Gabo and Pevsner sought to restore in the dynamic forms of their plastic works.

Discussions about constructivist sculpture began in regard to Tatlin’s Tower of 1919, which amounted to an attack on the academic tradition, and thus on classical “sculpted” and “cast” statuary, preferring the use of modern materials that would give a lighter dynamicity to the compositions, such as iron and glass. The strand of Gabo and Pevsner asserted that art, and sculpture away from its sole function, should exist independently of propaganda interests, concerning energy, force and rhythm. Indeed, they asserted, “Plumb line in hand, eyes as precise as a ruler, in a mind as taut as a compass...we build our work as the universe builds its, as the engineer builds his bridges, as the mathematician formulates his orbits.” It is from their manifesto that the name “constructivism” is most likely derived, since one of the directives was to “construct” art. Members would also be called artist-engineers.

In contrast, shortly afterwards, Aleksandr RodÄenko, who had previously joined and taken part in Suprematism, and Varvara Stepanova, his wife, published, also in 1920, the Program of the Productivist Group, convinced that, having now lost its traditional functions (that of religion, for example), art could regain meaning in the modern age, linked to industrial productivism: this is the concept of industrial design, that is, the choice, for the mass-produced object, of a form perfectly adherent to use.

Constructivist art had evolved to accommodate the idea of productivism, which took the aesthetic principles of constructivism and applied them to “everyday” art such as photography, fashion, furniture, film, and theater. The years of constructivism’s greatest development were between 1920 and 1925. El Lissitzky, after being in contact with MaleviÄ and Suprematism, had also joined Constructivism, believing that there was no conflict between art and technique. Then, when artist and designer Aleksei Gan published Konstruktivizm, which coincided with the official formation of the new Soviet Union in 1922, the movement was entering its productivist phase. Challenging pure abstraction and sculptor Naum Gabo’s thesis that Constructivism should devote itself exclusively to the exploration of abstract space and rhythm, Gan introduced his text that carried the declaration, “We declare uncompromising war on art!” Rather than autonomous formal research, which posed a risk of isolating the artist from society, the movement was oriented toward the realization of an overall aesthetic project, consistent with the political project of building socialism. Also from 1922 was the first exhibition of the “Society of Young Artists” officially defined as constructivist.

TheInstitute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK), which existed between 1920 and 1924, involved artists, graphic designers, painters, architects, scholars and sculptors who discussed the purpose and function of Bolshevik arts and culture. And the group called “LEF” (Left Front of the Arts) brought together literati and artists around the publication of the influential illustrated magazine of the same name, LEF, until 1925, and then New LEF from 1927 to 1929, through which the avant-garde was defended against the rise of Socialist Realism. Russia in these years was thus a nation full of vitality, reaching out for avant-garde solutions in the enthusiastic intellectual fervor that preceded, accompanied and followed the revolution as a new state and a new way of life was being created.

Soon, however, state bureaucracy once again took over from the freedom of artists: “Academics began to knock on the doors of the people’s commissariats,” wrote the poet Vladimir Majakovsky, meaning that the conservatives’ strength was superior to any attempt at renewal. After Lenin’s death (1924) and the advent of Stalin, Soviet art underwent a setback, due to the will of central power, arriving at a new form of realism in the service of imposed political ideology. Soviet opposition to the Constructivists’ aesthetic radicalism led to the dispersal of the group, whose experience had influence in other countries, however, and particularly on the German Bauhaus, which proved a fertile ground for the development of Constructivism. László Moholy-Nagy, a professor at the Bauhaus, spread Constructivist principles to both Dessau and Chicago in the United States, where (due to Nazi interference) the New Bauhaus was founded in 1937.

The new artistic language introduced by the Constructivists arose in relation to the materials and aesthetics of industrial mechanics, and was composed of non-figurative geometries in a synthesis of “space-time-movement.” Architecture and sculpture were revolutionized: the architectural style was cleansed of all decorative elements and references to the styles of the past with structures clearly based on ordered geometric forms to meet the functional needs of social planning. Sculpture, again in favor of geometric forms, moved away from the academic principles of the harmony of “mass” and “volume” to give way to “voids,” to render in three-dimensionality the movement in space. The fusion of the two forms of expression led to the movement’s most memorable works.

Tatlin’s most important work, also a work-symbol of Constructivism, is the already-named design for the 1919 Monument to the Third International, a gigantic spiral steel structure that was to have housed three rooms inside: the lower, cubic one, for legislative activity; the middle, pyramidal one, for meetings of administrative and executive bodies; and the upper, cylindrical one, for information offices. By design, the three rooms were to be enclosed by large glass walls, utopically alluding to the transparency, honesty, and clarity of the governing bodies that emerged from the proletarian revolution. The dynamics of the construction envisioned that the three floors would actually move in a rotational direction at different times. For the first time, a total unity between sculpture and moving architecture would be realized, the tallest tower in the world, along with the Eiffel Tower, which, however, was never built, becoming an emblem of communist utopianism. However, a model and scale reproductions of it were made, which helped spread the aesthetic idea related to the use of building materials such as wood (with which Tatlin’s Tower was initially to be completed), glass and metal for the construction of other new works of art and architecture.

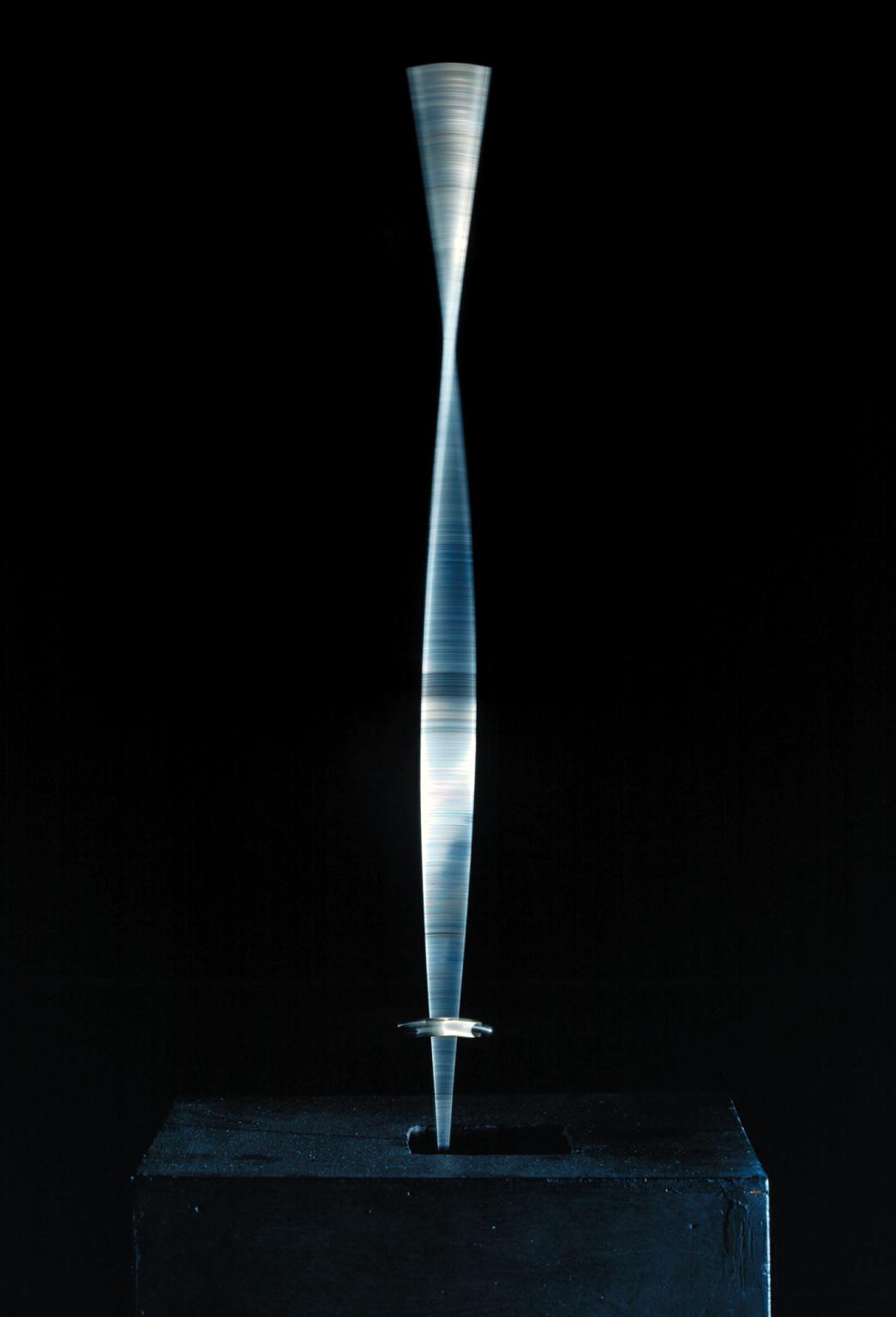

The Realist Manifesto, drafted by the brothers Gabo and Pevsner in 1920, then definitively affirmed the introduction of industrial materials and forms derived from the processes of modern technology; such as, for example, celluloid, the first plastic material in history, and galvanized metal with which Naum Gabo made, for example, Built Head No. 2 in 1916, one of his first works that anticipated the abstract kinetic sculptures for which he would become famous. The two brothers, as mentioned, opposed the idea that art should express specific political doctrines or satisfy prescribed utilitarian goals. From 1920 Kinetic Composition, in which a motor rotated a metal rod that, as it moved, created abstract images and volumes in space. Gabo was a forerunner of the art known as kinetic art, which would become established during the 1960s and 1970s, arguing that artistic expression should be about energy, force and rhythm.

The idea of constructing images that included dynamism and movement was common to most constructivist exponents, beyond expressive forms.

Rodchenko and El Lissitzky, had both joined and worked among the Suprematists and took their basic colors and figures and reformulated them in the name of constructivist goals and industrial productivism. With the intention of moving art beyond the confines of museums and thus into the sphere of everyday life, they devoted much effort to graphic design, understood as the perfect combination of text and image, form and content. Rodchenko, whose recognizable designs made use of bright colors and geometric shapes, produced one of the most iconic works of the Russian avant-garde: a photomontage featuring a joyful female worker shouting a message, the word “Knigi” (books). A perfect juxtaposition of photography, graphics and typography for an advertising poster for the state publishing house, in which the shapes of the circle, triangle and rectangle frame a photographic portrait of a woman (Lilija Brik, Majakovsky’s life companion and LEF activist,) who, as if using a megaphone, shouts hand to mouth a demand from the working class: Books (please)! In all branches of knowledge (1924).

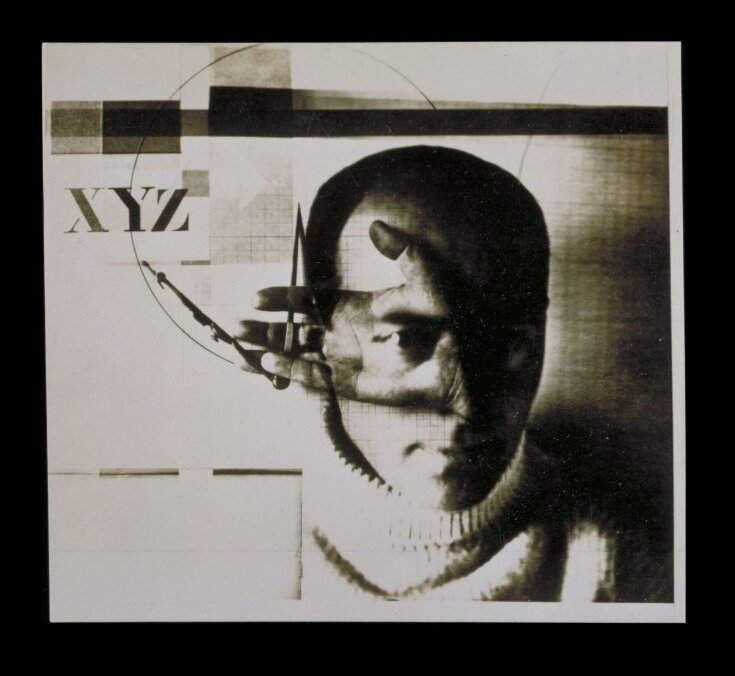

El Lissitzky, like Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova and others, also used the technique of photomontage, which became the preferred medium of these artists; but while his colleagues mostly employed it to support the productivist program, through product advertising, movie posters and posters, photocollage and promotional sketches, Lissitzky combined his shots while staying close to his more supremacist pictorial roots.

The artist declared that “No form of representation is so easily understood by the masses as photography,” which, with the text, perfectly suited the goals of a revolutionary art. In one of his most famous compositions, Self-Portrait (The Builder) of 1924, elements of collage, technical drawing and photography emphasize the role the constructivists had set for themselves: El Lissitzky stares straight ahead while his right eye seems to look through the center of his open palm. The same hand balances a compass above a partially depicted graphic work of his on the left side of the frame. The work symbolizes the unity of artistic vision and execution, where the artist is both the builder of his work and constructed by it.

|

| Constructivism. History and style of the Russian avant-garde movement. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.