Carlo Carrà (Quargnento, 1881 - Milan, 1966) was one of the personalities on whom Italian art of the early 20th century was best reflected. The painter adhered first to Futurism and then to Metaphysics without ever settling definitively in any one movement. Equally fundamental to the development of his artistic language were his studies of Tuscan masters, such as Giotto and Paolo Uccello. While still young he moved to Milan where he was able to visit museums and enrich his artistic knowledge. Important were the many trips he made to Paris, at the time the capital of art, where he was able to forge relationships with the Cubists and the Parisian intellectual milieu. Not only a painter but also a militant critic, Carrà contributed to various magazines, including Lacerba, L’Ambrosiano and Valori Plastici.

From 1939 to 1951, Carrà was also a professor at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts. Singular was his ability to interpret and summarize the main motifs and themes of the movements in which he participated: when he joined Futurism, Carrà managed to find a formal balance between plastic and dynamic motifs that he often declined into Cubist overtones. His approach to metaphysics was also highly original, imparting to the paintings of this period a slight movement and touch of originality that made him independent of the enigmatic works of Giorgio De Chirico or the meditative, silent canvases of Giorgio Morandi. Carrà immediately demonstrated a certain intuition toward the more avant-garde and modern artistic pursuits of the early twentieth century, without renouncing an artistic expression that was personal and original .

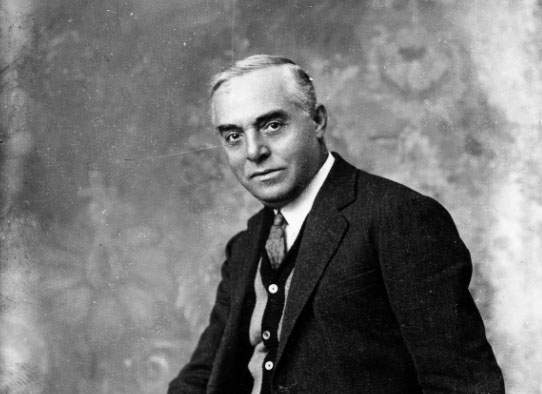

|

| Carlo Carrà in 1920 |

Carlo Carrà was born in Quargnento, in the province of Alessandria, on February 11, 1881. The fifth son of artisan Giuseppe Pittolo and his wife Giuseppina, Carrà spent his childhood in a rather humble, village environment. As a child he was struck by an illness that forced him to stay in bed for about a month, so to keep his days busy he began to draw and discovered his passion for art. In 1895 the Piedmontese painter moved to Milan to work as a palace decorator, yet during this period he led a rather uncomfortable and meager life. The city offered Carrà the chance to see museums and delight his eye by spending Sundays at the Brera Art Gallery and the Modern Art Gallery in the Castello Sforzesco. In 1889 he went to Paris for the first time where he got to see Delacroix, Gericault and the Impressionists. In 1909 he became a student of the painter Cesare Tallone at the Brera Academy where he was able to develop a figurative experience of the Divisionist type, and it was here that he befriended a number of artists, among them the Futurist Umberto Boccioni. In 1910 he met Marinetti and with him, Boccioni and Russolo decided to develop a manifesto to renew the Italian artistic language. Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini also joined the new movement, giving birth to one of the most important avant-gardes that marked the course of art history: futurism. In 1911 Carrà returned for the second time to Paris where he initiated his first contacts with Cubism, which intensified with his third trip to Paris in 1912 for the Futurist Exhibition at the Bernheim Jeune Gallery.

During his third trip to Paris in 1912 Carrà met many distinguished artists and intellectuals such as the artists Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, Medardo Rosso, and the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. Between 1912 and 1914 he contributed writings and drawings to the new magazine Lacerba, directed by writers Giovanni Papini and Ardengo Soffici. In Paris he developed and consolidated relations with the French Cubists with whom he spent a long period in 1914, and it was probably during this period that the crisis toward Futurism began to mature. His first “metaphysical” paintings dated from 1914. The war also involved Carrà, who was called to arms , but the wartime experience was short-lived as due to his poor health he was hospitalized in the military hospital in Ferrara, and it was in this tragic situation that he met the artists Giorgio De Chirico, Filippo De Pisis and Alberto Savinio.

Until 1919 he devoted himself assiduously to art, drew, painted and continued his studies on the masters of the Tuscan Quattrocento, which he had already undertaken a few years earlier. In 1919 he returned to Milan where he met and married Ines Minoja. After the marriage followed a period of inner crisis and great meditation: the painter painted little but drew a lot, producing a series of sheets that critics called the “purist phase.” In this period his artistic language was more spare and essential, anticipating some elements that characterized his new artistic language from about 1921 onward. The painter’s new poetics was also reflected in the writings that were published in the magazine “Valori Plastici” directed by Mario Broglio, of which Carrà was among the most assiduous contributors. In the early 1920s, Carrà had new contacts with the seascape that stimulated him to create new paintings and drawings. From 1926 Carrà spent his summers in Forte dei Marmi, and it was in Versilia, already so beloved by the poet Gabriele d’Annunzio, that the painter found landscapes suitable for experimenting with his renewed artistic language, which was more orderly and objective. The artist relied on the balanced division of planes and spaces to arrive at the ’balance between the concrete element and transfiguration. Alongside his paintings Carrà continued his “battle” for modern art with writings on criticism and aesthetic doctrine, particularly in the magazine “L’Ambrosiano,” for which he was art critic from 1922 to 1938. In the summer of 1965, the last he spent in Forte dei Marmi, he executed a large number of drawings, reworking, sometimes even years later, some motifs that were particularly dear to him. Following an illness Carlo Carrà died in Milan on April 13, 1966.

|

| Carlo Carrà, Exit from the Theater (1909; oil on canvas, 69 x 91 cm; London, Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art) |

|

| Carlo Carrà, Piazza del Duomo in Milan (1909; oil on canvas, 45 x 60 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Carlo Carrà, The Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1911; oil on canvas, 198.7 x 259.1 cm; New York, Museum of Modern Art) |

|

| Carlo Carrà, The Gallery in Milan (1912; oil on canvas, 91 x 51.5 cm; Milan, Mattioli Collection) |

|

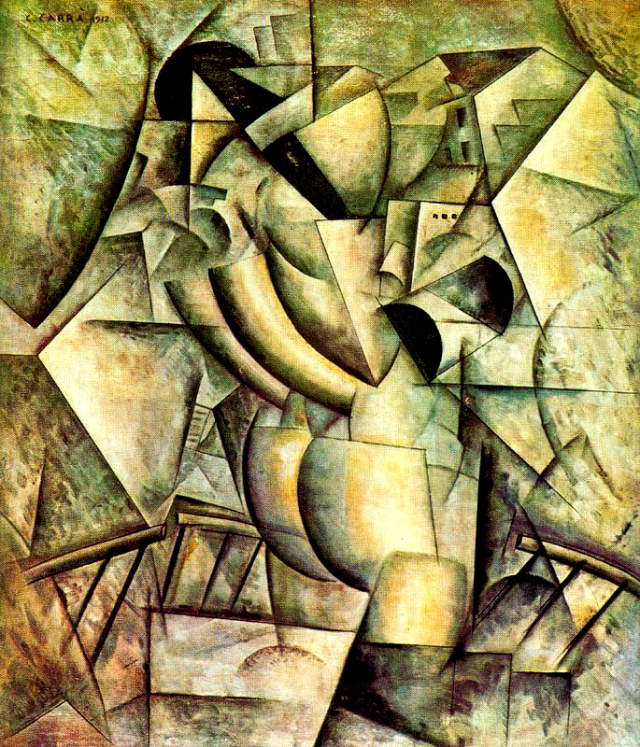

| Carlo Carrà, Woman at the Balcony (1912; oil on canvas; Milan, Jucker Collection) |

Carlo Carrà passed, like few others, through each of the neuralgic situations of Italian artistic culture, from Futurism to Metaphysics, but never remaining truly rooted in any of these movements. The artist was able to masterfully represent and interpret the cultural spirit of the early twentieth century. The earliest works that testified to Carrà’s Divisionist style were Exit from the Theater and Piazza del Duomo in Milan both dated 1909. In these two canvases the elements depicted are intermingled and although the composition and figures are still clearly recognizable there are elements that suggest a different view of space than the traditional one i.e. more dynamic. In Piazza del Duomo (1909), Carrà depicted the city square crowded with people, however it is interesting to note that he did not aim so much at the rendering of human components in the “academic” sense, if anything the painter wanted to convey the soul of the city: the noises, the chaos created by people and in general the urban atmosphere. In 1910 Carrà met the poet and painter Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founder of the Futurist movement. Marinetti’s open character and his intolerance of all academicism immediately seduced Carrà’s rebellious and anti-traditional soul, who in fact enthusiastically joined the movement. He thus began an intense artistic activity alongside the Futurist painters, which, however, ended quickly around 1915.

During the Futurist phase Carrà abandoned all kinds of pictorial symbolism of a Divisionist nature, preferring instead the dynamic simultaneity of human states of mind: the artist wanted to represent the emotion, the feeling of the human being in its continuous evolution. The Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1911) was one of the first works that testified to the painter’s adherence to futurism. The painting refers to an episode that occurred in 1904 when, during a general strike in Milan, the anarchist Angelo Galli was killed. In the work one can recognize the figures of the protesters running and the guards on horseback, but the interesting thing is that Carrà arranged the lines in such a way as to make the viewer perceive the impression of chaos and tumult. Further emphasizing this dramatic event are the colors: red accentuates the aggressiveness and confusion of the scene while the yellow in the background inflames the painting. The 1912 work The Gallery in Milan was one of the most emblematic works of this phase. Indeed, the canvas was modulated through lines of force and the interpenetration between background and figures typical of the Futurist style. The work depicts the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan, the commercial heart of the city with clubs, stores and cafes. In the upper part a complex architecture surrounds the famous dome of the gallery, while the lower part is dominated by the crowd of people, shaped according to a curvilinear and chaotic movement that indicates the passage of figures. The work alludes, slightly, to traditional altarpieces, not only because of its longilinear progression but also the relationship between order, in the upper part, and disorder, in the lower part. For Carrà, architecture, the city and modernity took the place of the saints and madonnas that once appeared in Renaissance canvases.

Another seminal and equally symbolic work was Woman on the Balcony (1912) in which a vague Cubist flavor emerges, especially in the use of contrast between the close subject and the space behind it but also in the choice of colors. Unlike Cubism Carrà gave a sense of movement not present in the still lifes of Braque and Picasso, and this indicates the Piedmont painter’s strong sense of originality and autonomy. The futurist style devoid of figurative elements emerges in the work, but nevertheless the woman’s body evokes a certain sensuality. Carrà succeeded in conveying the lady’s vague feeling of nudity by creating the veiled image of a provocative woman facing a balcony.

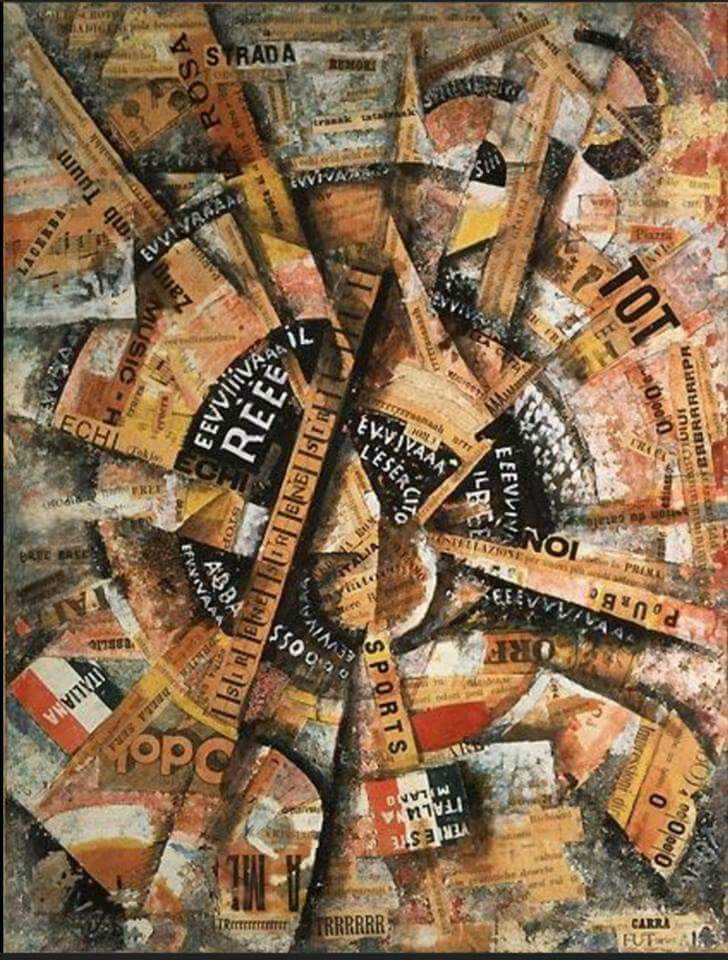

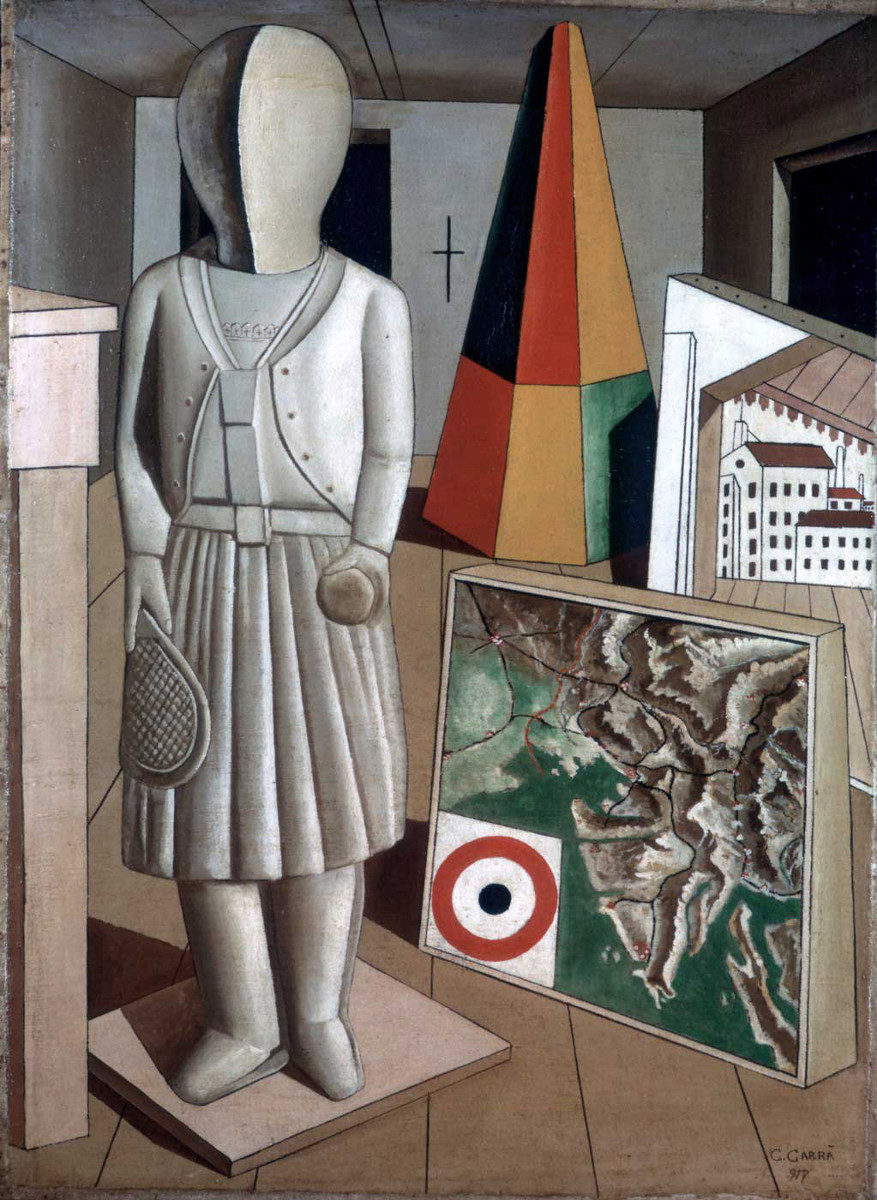

Carrà’s multifaceted character was also evident in Manifestazione interventista (1914), which he made toward the end of his Futurist period. It is a collage (a technique used to create works through the use of paper, newspaper sheets, magazines, and so on), in which the artist depicted the twirling of flyers thrown into the air from an airplane on Pizza del Duomo in Milan. The most interesting aspect of the work was that Carrà did not depict human figures or landscape elements, but through the clippings of the leaflets, the phrases quoted, and the fan-like pattern, evoked the confusion and chaos of a political demonstration. Formally, the work presents itself to the viewer as a centrifugal vortex of signs, while the colors contribute to this sense of expansion. The surface was made with the practice of collage in which Carrà used newspaper clippings, and some phrases or words are recognizable: from the center “army,” “yay,” “down with it,” but there are also words such as “zang tumb tumb” i.e., those used by Marinetti in a 1914 poem. These are all terms that can be traced back to the slogans of the demonstrations in the Italian squares in the aftermath of the Sarajevo bombing, an event that started World War I. After his brief but intense Futurist career Carlo Carrà had a “second revelation” between 1916 and 1917, namely metaphysical art. His main point of reference was Henry Rousseau but he also looked to traditional Italian art, particularly Giotto, Paolo Uccello and Piero della Francesca. In 1916 he painted The Antigraceful, a work with a rather archaic and grotesque character. The work depicts a little girl in the center, flanked by a trumpet and a little house, and everything seems to twirl freely in the air. The painting was defined by a few components, deliberately simplified, and detached from each other where the checkerboard floor seems to be the only real element. In this painting the painter rejected the dimension of space and time in order to embrace a more primitive and archaic language that in fact also emerged from the choice of colors.

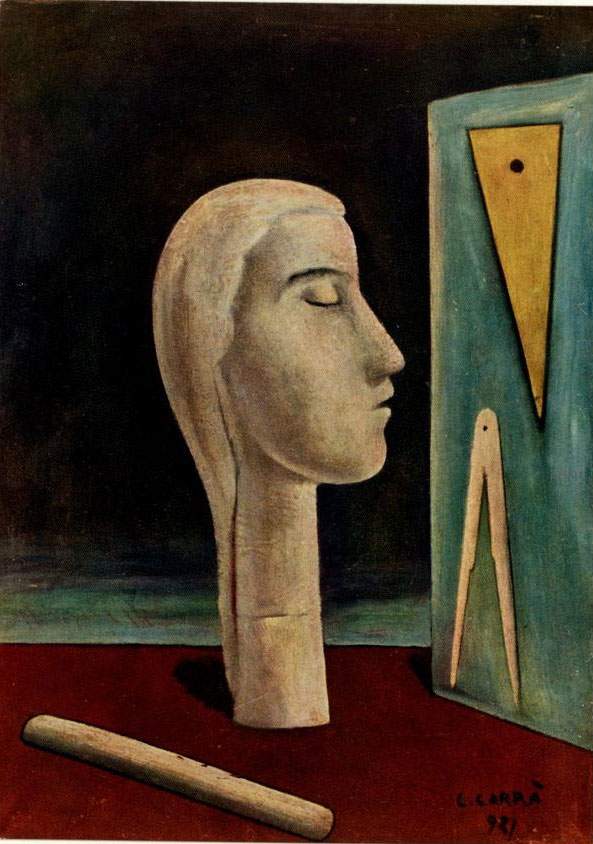

In 1917 he met Giorgio De Chirico in Ferrara, with whom he had a brief association, and in the same year he painted The Hermaphrodite God, in which he took up the theme of the mannequin and the timeless man, so beloved by Da Chirico. At the center of the canvas is a visibly and deliberately disproportionate mannequin that is placed in an environment that is too small, thus suffocating. The lack of genitalia and the benedictory greeting evoke the figure of an angel. Two other works that facilitate the understanding of Carrà’s metaphysical phase are Il cavaliere dello spirito occidentale (1917), in which the mannequin on top of the running horse becomes more dynamic, echoing in some ways the Futurist theme of movement, and La musa metafisica (1917), a work belonging to the Mattioli Collection. In the canvas, the mannequin was modeled with chiaroscuro in this choice Carrà resumed in some respects the Renaissance technique. The dominant color palette is that of grayish contrasted by the bright colors of the prism and the plastic. The Engineer’s Lover (1921) was one of the most famous works of Carrà’s metaphysical period. In the center of the painting a sculpted face lies motionless and enigmatic. In front of the face, however, is a panel with a square and a compass, which is supposed to symbolize the role of the engineer, but also the painter’s new artistic pursuit that was based on order and composure. The dark background highlights the absence of time and space, almost evoking a dreamlike dimension.

A further turning point in Carrà’s artistic language occurred around the 1920s, with his membership in Mario Broglio’s Valori Plastici magazine, to which the artist collaborated for a long time. From this time on, the painter was increasingly inclined toward the recovery of classicism and tradition. The search became more rigorous and rational, as already anticipated by the work L’amante dell’ingegnere in the two elements of the compass and the square. The most representative work of this period of “return to order” was The Red House (1926), in which the elements depicted are presented first and foremost as volumes. The painting is dominated by a large red house in the center, from which in fact the work takes its title, devoid of detail but mighty in its structure; to the left another building in gray-green hues precedes the central house. In the foreground, on the other hand, resting on a windowsill of a house, are a vase, a sheet and a small cube. On the horizon it is possible to make out the vegetation of a landscape that is, however, immediately blocked by the two large cubes that dominate the canvas. Carrà developed form by following the objective datum but at the same time brought out an archaizing language. He also rediscovered the wonder of nature by staying during the summer in Forte dei Marmi, a place where he was able to contemplate landscapes and pursue his artistic research. Carrà’s artistic career spanned almost all the events of early 20th century Italian art, and although he was not the leader of any movement his artistic and representational strength was extraordinary.

|

| Carlo Carrà, Interventionist Manifestation (1914; tempera, pen, mica dust and paper on cardboard, 38.5 x 30 cm; Mattioli Collection, on deposit in Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) |

|

| Carlo Carrà, L’Antigrazioso (1916; oil on canvas, 67 x 52 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Carlo Carrà, The Knight of the Western Spirit (1917; oil on canvas, 52 x 67 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Carlo Carrà, The Metaphysical Muse (1917; oil on canvas, 90 x 62 cm; Milan, Mattioli Collection, on deposit at Museo Poldi Pezzoli) |

|

| Carlo Carrà, The Engineer’s Lover (1921; oil on canvas; Milan, Private Collection) |

Carlo Carrà’s works can generally be found in museums that house 20th-century art. In particular, the Mart in Rovereto (Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art), the Museo del Novecento in Milan, and the Galleria Nazionale d’arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome house most of his most representative works from both the Futurist and Metaphysical periods. Other major works are part of the Mattioli Collection, a very important collection of Italian art, particularly Futurism and Metaphysics. Twenty-six masterpieces from the collection, after notification from the Italian state, are now indivisible. The collection was loaned to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice until 2015, and now the soon-to-be second one has been granted to the Pinacoteca di Brera, so this is where you can see some key works from Carrà’s artistic career, including Manifesto Interventista (1914), La Galleria di Milano (1912), and L ’amante dell’ingegnere (1921).

Other museums where it is possible to see the painter’s works are: the MoMa in New York, which houses a series of drawings and The Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1911); Paris, at the George Pompidou Center; in Vatican City, at the Vatican Picture Gallery, where the third version of Daughters of Loth (1940) is kept; and finally, the Roberto Longhi Foundation in Florence houses a good number of Carlo Carrà’s paintings.

|

| Carlo Carrà : life and works of the futurist and metaphysical painter |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.