In the 1960s many artists adopted performance as a new mode of expression, choosing to present their own bodies, or those of others, as their preferred medium of operation. This new artistic dimension was the result of historical processes that led to the centralization of the individual, who in the 1960s was placed in the foreground, made the subject of existentialist reflections also thanks to those opinion movements that acted for the claim of the rights of the person, of women, of the body, of sexual orientations. Among the first artistic experiences that brought the body to the forefront were, in 1960, the Anthropométrie of Yves Klein (Nice, 1928 - Paris, 1962), where some women left their own blue traces on a canvas. In Italy, Piero Manzoni (Soncino, 1933 - Milan, 1963) signed the nude body of a model, thus making a Living Sculpture (1961). The moment when the body as a medium fully occupied center stage was when the artistic investigation of Body Art was consolidated, with actions often reporting conditions of extreme physical or psychological violence that were presented in front of an audience, called upon to participate emotionally and sometimes even physically.

These were temporary forms of artistic representation, a form of direct communication close to the world of thehappening, with the aim of provoking a rupture within the system of more conventional social values, a goal shared with the Fluxus group. The body artists ’ performances not infrequently disconcerted the audience, captivated by the unusual or brutal actions. In this disturbance of the senses, the body is both protagonist and site of symbols, transmitter of universal themes.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Europe and the United States were traversed by vast movements of opinion, represented mainly by the working classes and that part of the younger, student population. Denunciations were directed at the bourgeois system, capitalism and institutions; consumerism and all kinds of authoritarianism were condemned. The fundamental freedoms of the individual, human rights were claimed: the emancipation of women, the right to be able to make decisions about one’s own body, the freedom to express one’s sexual orientation. In this sense, 1968 was the most significant year, as there was a concentration of events that involved radical transformations.

It was inevitable that the art world was also affected by these changes: the hottest issues entered as protagonists of the new modes of expression, the cultural scenario began to question the most canonical schemes, proposing alternatives, coming out of the usual structures of art making. Anticipations of this attitude can be identified in the activity by French artist Marcel Duchamp, who was revolutionary and pioneering in his pursuit of the idea of conceptual art.

That idea later flowed into the Surrealist and Dada circles and into early twentieth-century avant-garde cinema. The convention that saw the work of art as a mere aesthetic artifact, intended for an audience limited in passive contemplation, began to be overcome. In these years of social turmoil, the consideration of the work of art as an object was overridden in favor of its idea: thework-concept was placed in direct dialogue with the user, who now occupied a new position in relation to the object, no longer contemplative, but active and tending to constitute an exchange. It was an understandable relocation if one looks at contemporary events: just as the individual gained a new centrality thanks to the socio-cultural phenomena of those years, so the individual viewer came to be involved in an equal position, face to face with the work. Conversely, the work of art lost that mythical aura of remoteness, became democratized by coming closer to the audience in order to sustain a confrontation, an exchange through which it found its raison d’être. This kind of attitude in art and culture made its first appearance in the coveted modern ballet of choreographer Merce Cunningham; in John Cage ’s experimental music in America in the 1950s. The 1960s saw the spread of the practice ofhappenings, performance art that sought the aestheticization of everyday gesture; the Fluxus group confronted and informed about contemporary problems.

Viennese Actionism led artists to meet in sharing the idea of one’s body as the main element and medium of transmission of aesthetic messages and values. These phenomena ledbodily investigation to full fruition, which triumphed with Body Art. In particular, Viennese Actionists played an important role in reclaiming their freedom of artistic expression, especially considering the hostility of the Austrian territory. The work of Hermann Nitsch (Vienna, 1938 - Mistelbach, 2022) presented exhibitions and reconstructions of rather ferocious pagan rituals, using blood and displaying animal corpses. The violent component investigated by Nitsch is an element that recurred by slipping into the practices of body artists.

Body Art emerged in its definition from the 1970s in America, where the idea of thinking of the human body in the role of artistic material became widespread. As in thehappening, Body Art proposed expressions with a theatrical structure; they were temporary scenes that chose not to last, which is why they happened to be filmed and photographed. The body became an arena, a place of action; corporeality was understood as a possibility to convey messages of universal reach. One goal, also shared by the Fluxus group, was to provoke a disruption in the perpetuation of traditional artistic patterns, acting alongside the political, social and cultural movements that were rampant in the 1960s.

Body Art considered the body as an alternative to traditional materials, a load of vital energy with its natural possibility of movement. In some cases, this kind of artistic pursuit also walked a sadomasochistic line of expression. Pain, wounds, cuts and other traumatic expedients became part of the aesthetic dimension proposed by body artists. According to this modus operandi, the artists acted in open confrontation with the public: using the body and a space they tried to convey a value that was relevant and current. The body artists intended to provoke a collective shock in visitors, stimulating an incisive participation and reaction. Hence, the ultimate goal was also to induce viewers to have acathartic experience.

As anticipated, Body Art emerged in the United States as the use of the body understood as an artistic material became more widespread. In New York, Vito Acconci (New York, 1940 - 2017), the son of Italian immigrants, would chase several randomly chosen passers-by for hours; inside museums, he would get excessively close to visitors to elicit annoyed reactions from them. In all those actions, people were unaware of what his goals were, namely the investigation of the sphere of interpersonal relationships. By violating interpersonal physical distances, Acconci disregarded social conventions thus challenging the most established behavioral patterns.

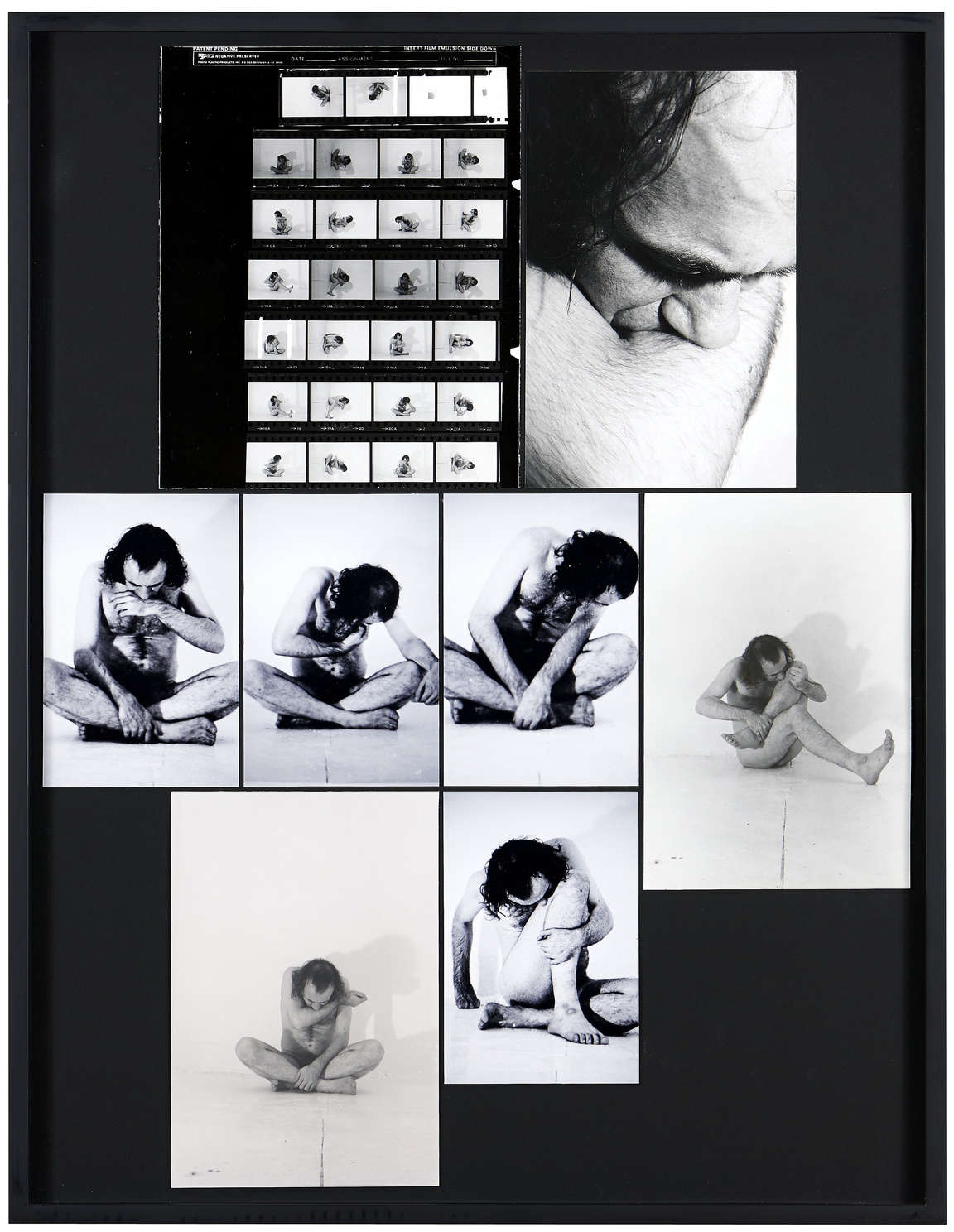

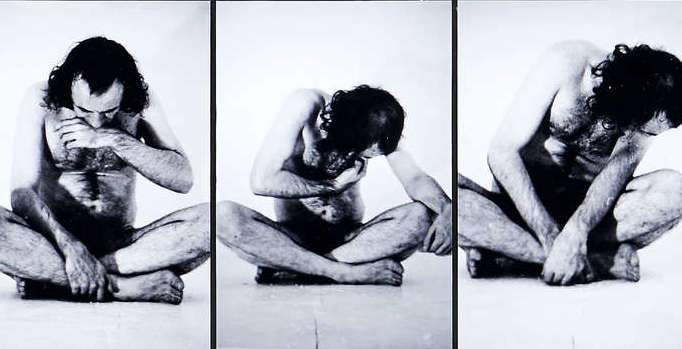

Subsequently, he went on to undertake a raw knowledge of his own body, bringing it to the fore in his artistic research. With Trademarks , in 1970, he began biting himself violently, becoming both the active subject and passive object of the work. The impressions left by the teeth on his own flesh were immortalized by the photographic medium, covered with ink and then printed on paper.

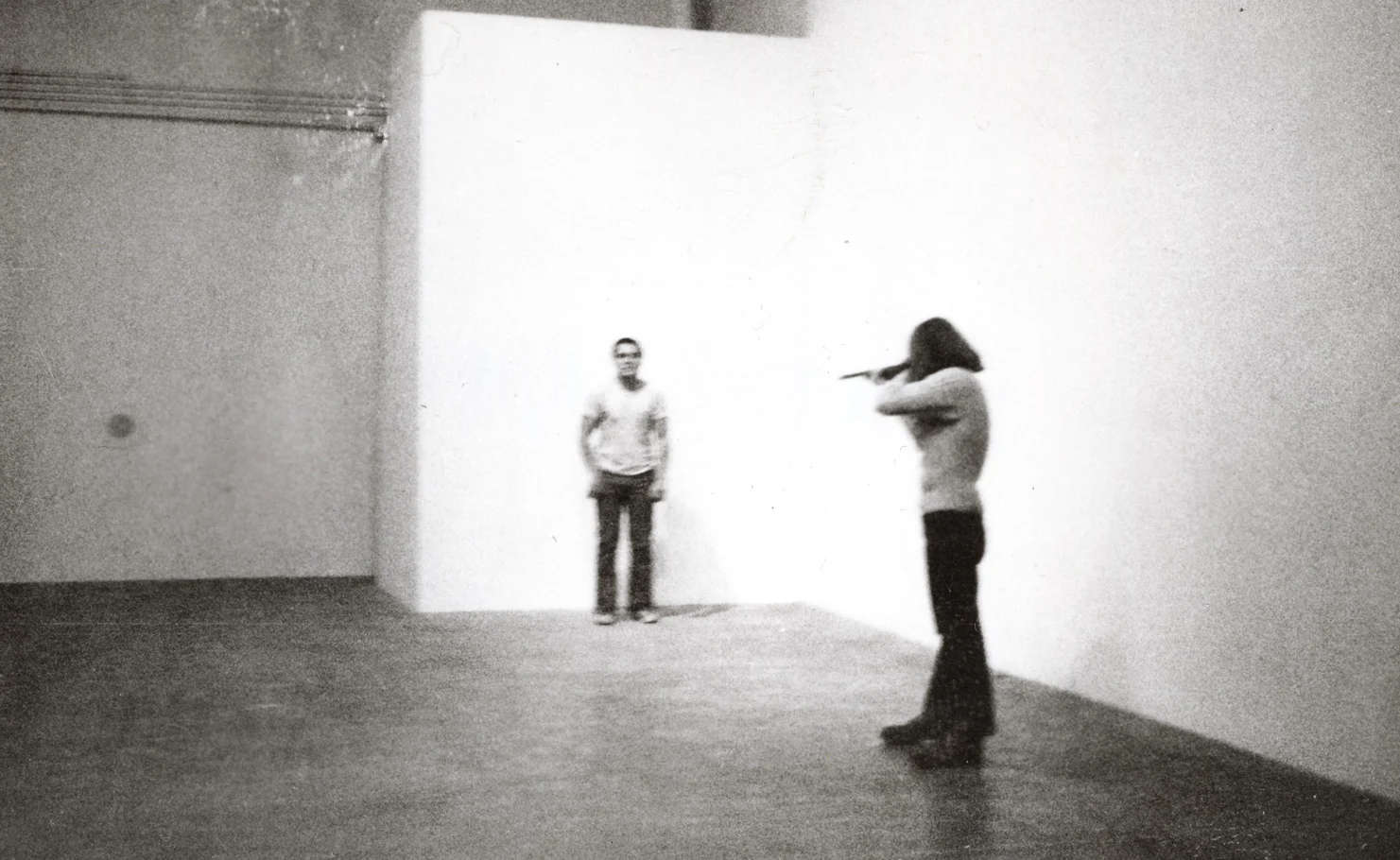

The provocative action was directed at an analysis of violence, often extended to a historical and social context as well. The initiative was also shared and embraced by Chris Burden (Boston, 1946 - Topanga, 2015), who in 1971 had his friend shoot himself with a .22-caliber rifle. The action was called Shoot, took shape in a gallery in California, in front of a consenting, witnessing audience, vulnerable to the trauma that would occur. With Shoot, Burden denounced the habituation that the American people had developed in the face of violence. Contextually, he investigated that emotional tension, the suspense that invests those who know they are about to be hit by a bullet.

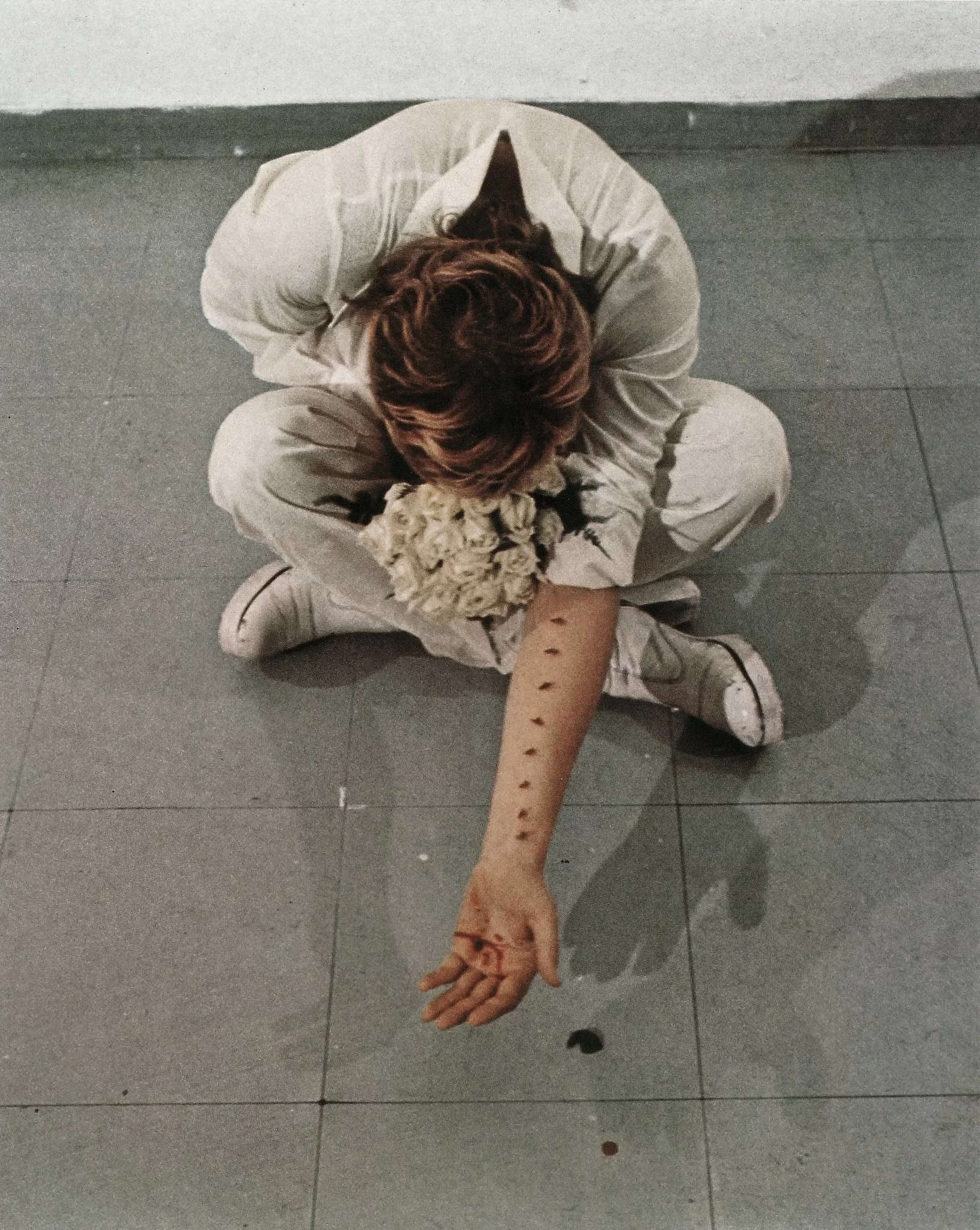

In the European context, the French artist Gina Pane (Biarritz, 1939 - Paris, 1990) distanced herself from the operations of the Shareholders, delineating her Body Art in a more violent sense. The artist inflicted real wounds on herself, provoking and enacting concrete suffering using her own body. For each performance, Gina Pane, accompanied punctually by a white dress, exhibited her own torment, to communicate to the audience how dangers, sacrifices, and suffering are omnipresent, even in moments of apparent happiness and beauty, too fragile to last. In 1973 the artist clutched a bouquet of roses, always the flower symbolic of romantic love, and then thrust thorns into her forearms: with Sentimental Action, Gina Pane wanted to express how even the most poetic and profound feelings can bring pain.

Marina Abramović (Belgrade, 1946), active since the 1960s, marked her artistic research with the analysis of interpersonal relationships, searching for the troubled reactions of individuals among her audience. She knew and expanded the extreme limits of her body, trying to overcome the possibilities imposed by the human mind. In Naples, in 1974, the Serbian artist put her mind and body to the test. In the Studio Morra gallery she gave life to one of the most shocking actions in the history of Body Art (the action was called Rhythm 0) by inviting those present to use the most diverse objects on her, including even ropes and scissors. Marina Abramović soon found herself with her clothes torn, scarred, and with a loaded gun pointed at her head. In the great emotional tension of that moment, the performance conveyed the importance of the theme of violence on the weakest, and, especially, that exerted on women.

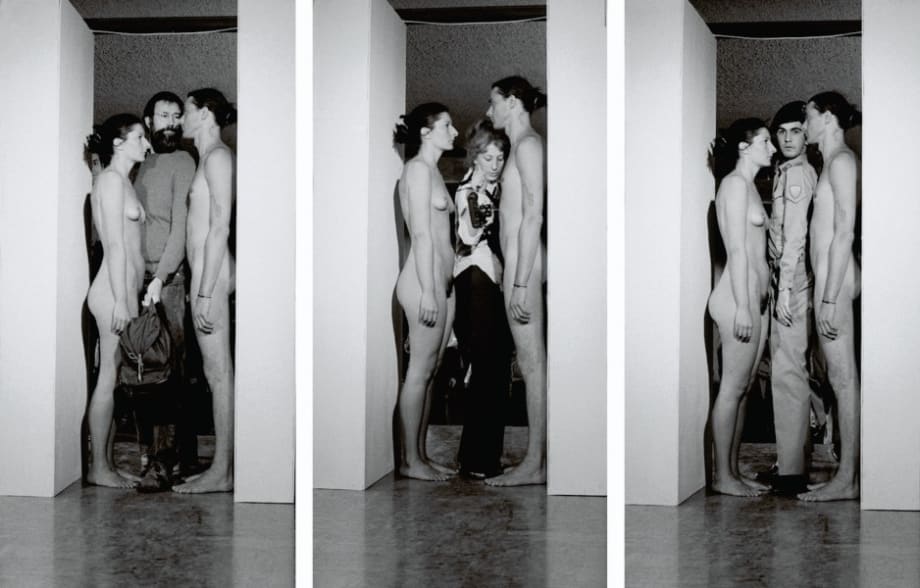

Together with the German artist Ulay (Uwe Laysiepen, Solingen 1943 - Ljubljana, 2020), Abramović created works in pairs. The Imponderabilia event in the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Bologna on June 2, 1977, is famous. The two artists leaned against the walls of a narrow passage created at the museum’s entrance, completely naked, making physical contact inevitable for anyone who wanted to enter the Gallery. The most diverse reactions of visitors, imponderables in fact, gave meaning to the action performed.

Among the themes addressed by the artist in his performances were eroticism, women’s bodies, and the violence of the Balkan war. Balkan Baroque was a performance performed in 1997 at the Venice Biennale. Marina Abramović was awarded the Golden Lion: the action consisted of sitting on a pile of cattle remains. The artist picked up the bones, cleaned them of the remaining flesh and cartilage. The ritual fulfilled its cathartic sense in condemning the errors committed in the Yugoslav wars.

In Germany, Rebecca Horn (Michel Stadt, 1944) embarked on an alternative line within Body Art. Her artistic expression involved the implantation of prostheses: during a period of hospitalization that forced her into immobility, she designed devices that allowed her movement. This condition resulted in a performance, Finger Handschuhe, a device that stretched the artist’s fingers, with which she could grasp objects. This possibility imposed a different awareness in simple movement and contact with the external environment.

The Swiss Urs Lüthi (Kriens, 1947), on the other hand, investigated the dimension of makeup and disguise. In Selfportrait with Ecky, Lüthi in 1974 manipulated his own sexual identity, trying to make his own profile as feminine as possible and to make it coincide with that of his girlfriend. This exploration in sexual identity has its roots in the work of the historical Vanguards. The artist Marcel Duchamp undertook this quest in the 1920s, having himself photographed by the American Man Ray dressed as Rrose Sélavy. The superimposition of profiles operated by Urs Lüthi was immortalized in a shot, now in a private collection.

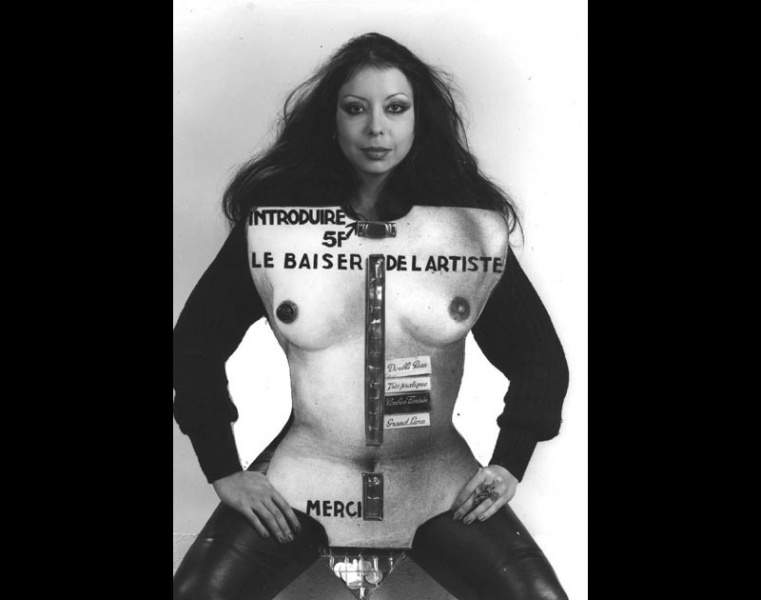

Body art was a more than fertile field forartistic engagement in the feminist cause. In addition to the artists mentioned above, mention should be made of the activities of the French ORLAN (Mireille Suzanne Francette Porte; Saint-Étienne, 1947), who in 1977 staged the sale of her own body during theaction Se vendre sur les marchés en petits morceaux (“To sell oneself on the markets at small prices”) leading to reflection on the actual decision-making power and disposition women have (or should have) of their own bodies.

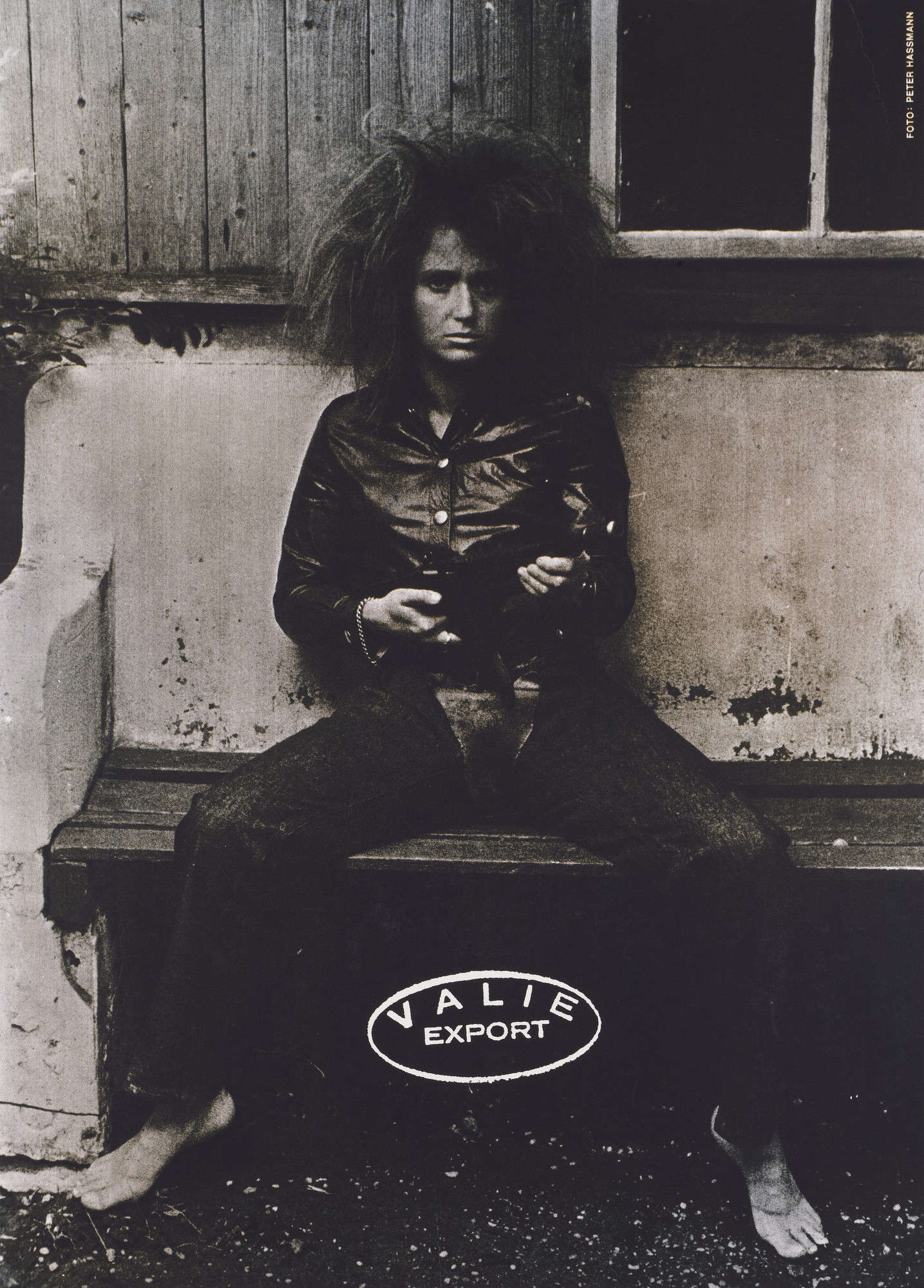

Valie Export (Waltraud Lehner; Linz, 1940), in 1968 performed Aktionshose: Genitalpanik (Action Pants: Genital Panic) by walking into a Munich porn theater with her pants cut at the crotch to reveal her own pubic hair. The audience was inevitably impressed and offered different reactions: some got up and left, some stayed and said “this is something new, I might as well think about it.”

|

| Body art, origins, history, major exponents |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.