Bauhaus. Origins, development and main exponents of the school

The Bauhaus was a higher institute of art education founded in 1919 in Weimar, Germany, in the cultural-historical context of the Weimar Republic (1919-1933), to promote a new educational method that could integrate art and industrial craftsmanship and the unity of different artistic activities in the service of the concept of the "total work of art."

Das Staatliche Bauhaus, a new state school of Architecture, Design and Art was born from the merger of the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) headed by Henry van de Velde and the Hochschule für bildende Kunst (Academy of Fine Arts) founded and directed by Hermann Muthesius, and took the name “Bauhaus,” which can be translated as “house of building,” and is derived from the inversion of the German word “Hausbau,” “building a house.”

The founder and first director was the architect Walter Adolph Gropius (Berlin, 1883 - Boston, 1969), his successor in 1928 Hannes Meyer (Basel, 1889 - Lugano, 1954), who was followed from 1930 until its closure in 1933 by Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe (Aachen, 1886 - Chicago, 1969), who together with Gropius was one of the most important and influential architects of the 20th century. The Bauhaus school, in which some of the leading figures of the time took part as teachers, determined an influential artistic movement that redefined the aesthetics and functionality of arts and crafts, founding the new contemporary design and a striking architectural style, both in Europe and the United States. The school was first based in Weimar from 1919 to 1925, then in Dessau until 1932 and finally in Berlin in its final months and before the Nazi regime in 1933 imposed its end, considering it too open to international trends.

Origins and Development of the German Bauhaus School

What was the first site of the Bauhaus school in Weimar had been built between 1904 and 1911 to house the studio of sculptors from the former Saxon Grand Ducal School of Arts and Crafts designed by that institute’s director, Art Nouveau architect Henry van de Velde. By 1915, architect Walter Gropius had taken over the school, and it was through the merger four years later of this institution with the Academy of Fine Arts that the new Bauhaus school was formed. In conceptual terms, it grew out of the late nineteenth-century ideal of bringing together the fine and applied arts, and was formed to reform art education. In the same 1910s, the development of Russian Constructivism promoted a fusion of art with design. When the Bauhaus opened its doors, Gropius imagined that it should encompass the totality of artistic media, sculpture and painting, industrial design and graphic design, typography, interior design and architectural design, of course.

The curriculum was structured as a wheel made up of concentric rings, with the outer ring representing a six-month preliminary basic course, and the two middle rings indicating intermediate courses of the students’ choosing, complemented by their practical work in the accompanying disciplines. Workshops in carpentry, metalwork, ceramics, glass, wall painting, weaving, graphic design, typography and stage design... The program then placed “construction”(Bau) at the center of all activities, at the center of the wheel, where architectural design was placed.

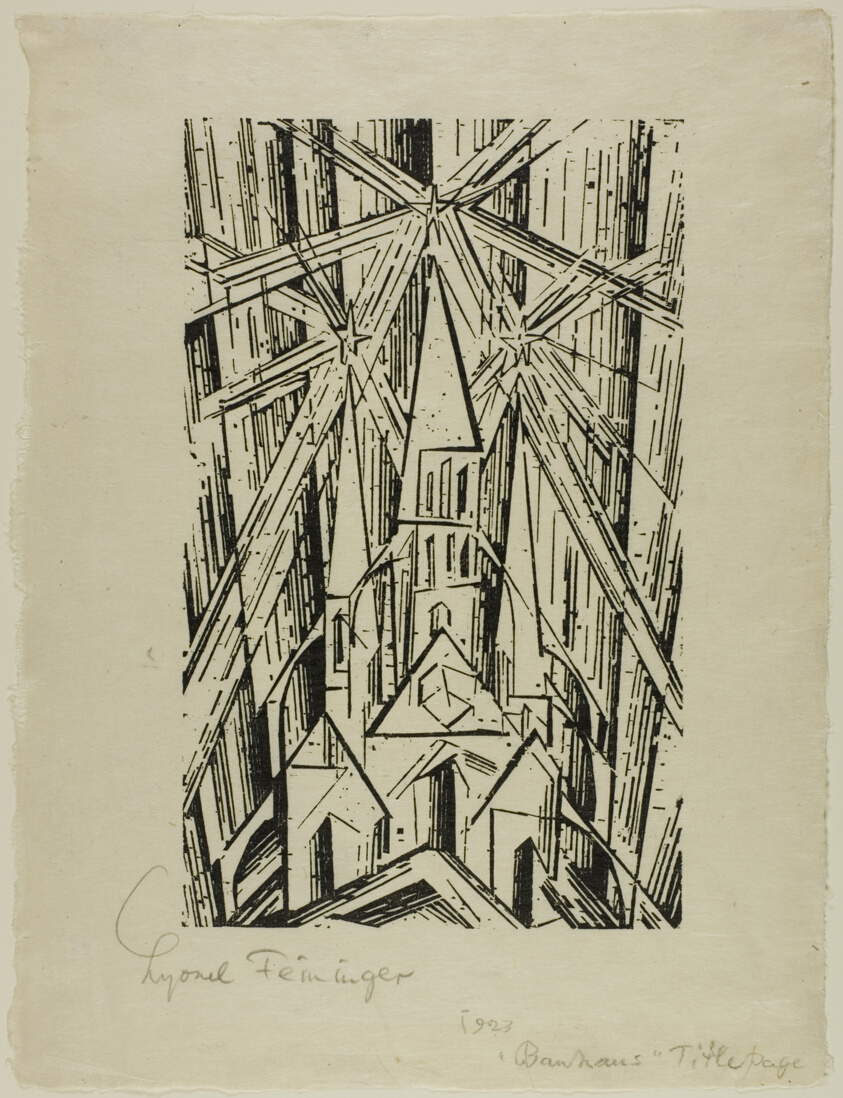

A key goal of the Bauhauspedagogical approach , adopted for all courses, was to eliminate competitive tendencies, to promote not only individual creativity but also a sense of community and shared purpose, and was based on collaboration between teachers and students. Instead of copying from models, as was still done in traditional art academies, personal expression was encouraged. An educational course with such a structure was unprecedented, and the choice of teachers to be involved was decisive in the development of the various disciplines. Gropius succeeded in gaining the support of renowned avant-garde artists. The painters Johannes Itten (Süderen-Linden, 1888 - Zurich, 1967) and Lyonel Feininger (New York, 1871 -1956) and the sculptor Gerhard Marcks (Berlin, 1889 - Darmstadt, 1981) were among the first appointees in Weimar. They followed over the years from Josef and Anni Albers, Herbert Bayer and Marcel Breuer, to Lyonel Feininger, Vasilij Kandinsky and Paul Klee, Theo van Doesburg, Oskar Schlemmer and others.

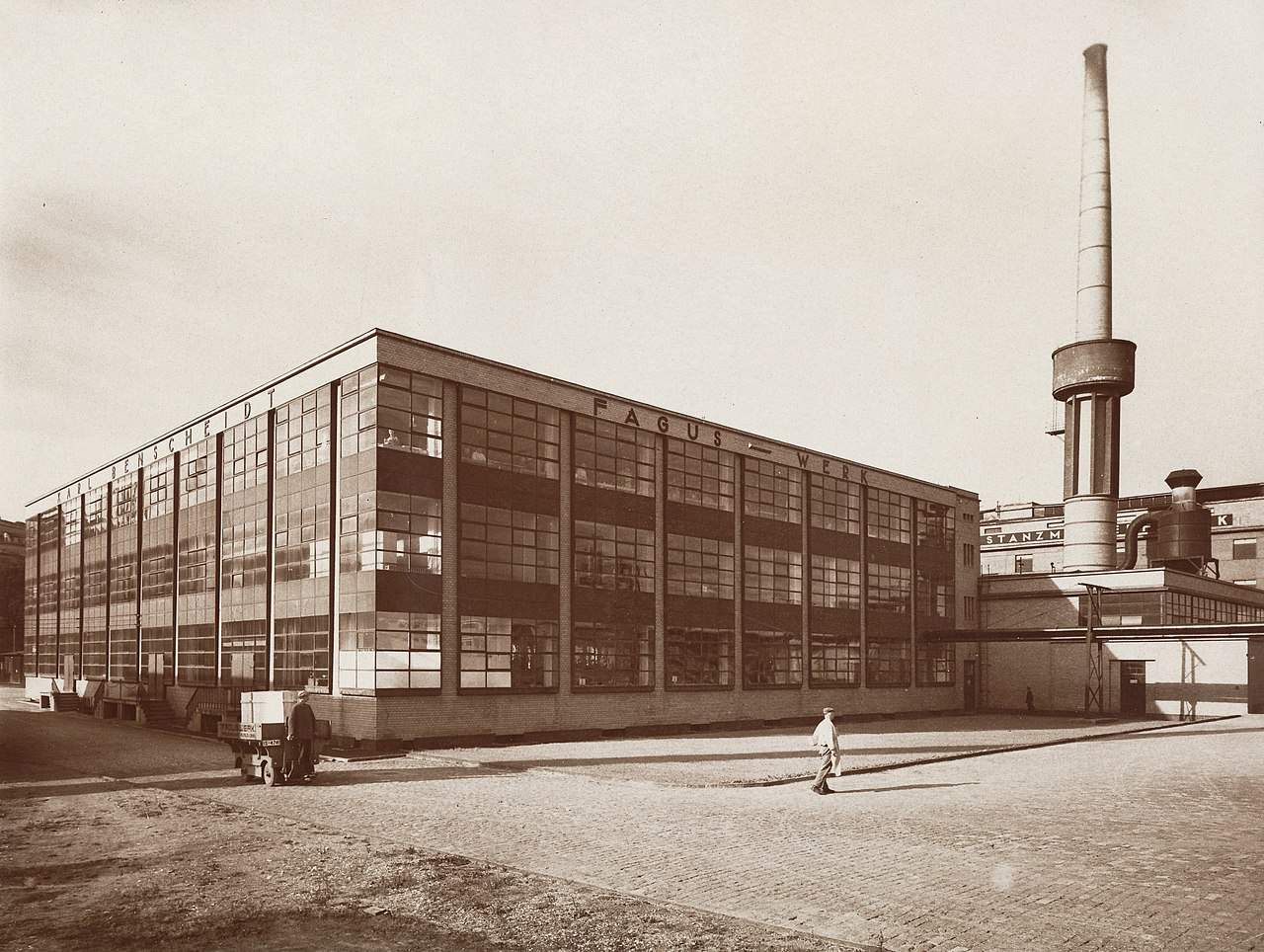

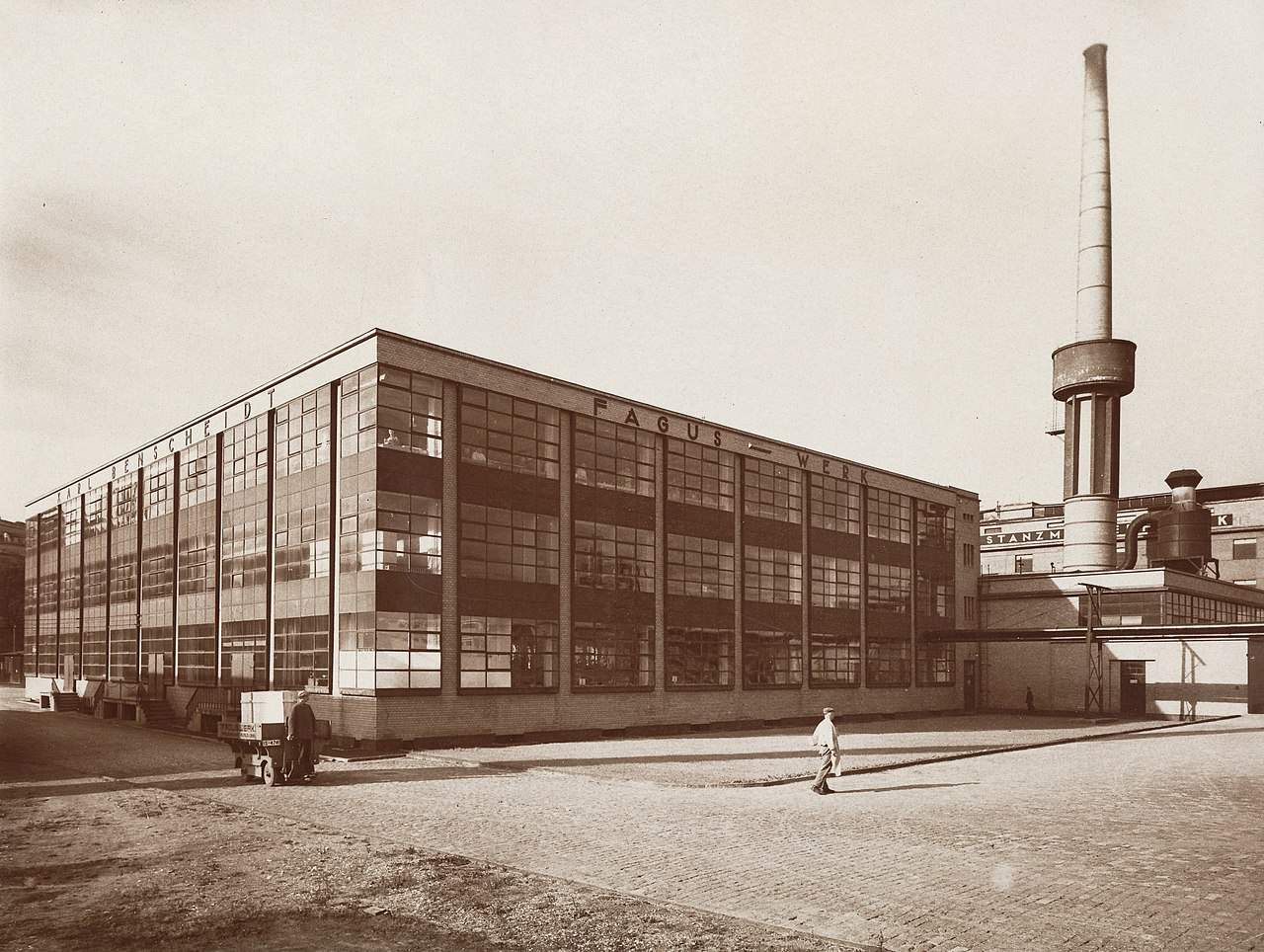

Despite the short history of this institution, from 1919 to 1933, various aesthetic influences combined over time. When Itten left the school in 1923, the year in which the movement’s first exhibition was held, he was replaced by László Moholy-Nagy, who reshaped the curriculum by embracing technology and a social function of art. Until in 1925 the school moved to the German industrial city of Dessau, beginning its most fruitful period of activity. Gropius designed a new building for the school that has since become not only the symbol of the Bauhaus but also a landmark of modern, functionalist architecture. It was here in 1927 that the school could also have a full-fledged architecture department. In 1928 Gropius resigned, handing over the directorship to Swiss architect Hannes Meyer, who headed the architecture department himself. However, in 1930 he was dismissed. Architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a famous proponent of functionalist architecture, like Gropius, who determined the so-called International Style, became director. From Dessau came such texts as Klee’s Pädagogiches Skizzenbuch (Pedagogical Sketchbook), Moholy-Nagy’s Malerei, Photographie, Film (Painting, Photography, Film), and hundreds of drawings for buildings and utility objects produced on an industrial scale.

In 1932, with the Nazis in power, the school was again relocated, this time to Berlin, for the last year before its final closure. In Berlin, the Bauhaus survived briefly and with fewer resources than it had enjoyed in previous years, with the institute emptied of its most influential personalities. In 1933, the school was closed indefinitely under intense political pressure and threats.

In the following decades, after World War II, the influence of the Bauhaus would shift along with its former members, many of whom were forced to flee Europe. In the United States, Josef Albers became an art teacher at Black Mountain College in Asheville, László Moholy-Nagy in 1937 founded the New Bauhaus in Chicago, where Mies van der Rohe also moved and became director of the Armor Institute’s architecture department, while Gropius at Harvard became a professor at the Graduate School of Design. The spirit of the Bauhuas also survived in innumerable reproductions and quotations of the furniture and fittings, objects and graphics produced during the fourteen years he worked in Germany.

Style and applications of the major exponents of the Bauhaus

In the founding act Gropius defined the Bauhaus as a “vast system” with “the theoretical activity of an art academy combined with the practical activity of a school of arts and crafts.” In fact, the first poster of the new school featured a woodcut by Lyonel Feininger showing an ancient cathedral of which the central tower symbolizes architecture, and the side ones sculpture and painting(Cathedral of Socialism, 1919). Just as in the building sites of the great Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals architects, sculptors, painters, stonemasons, carpenters, and all sorts of craftsmen worked together, so, only with the cooperation of all professional skills and without pre-eminence of one over the other, could the creation of the modern, democratic work be achieved. The Bauhaus idea was to train artists with various specializations who would conceive a new Gesamtkunstwerk or “total work of art,” of whicharchitecture would be the "complete construction, the final goal of the visual arts."

Symbolic of this Bauhaus vision is the building that Gropius designed and succeeded in having built in Dessau as the headquarters of the school, where the use of glass walls would ensure light-filled interiors, even allowing a view from the outside of the functional interior divisions, to this day one of the most important architectural works of the twentieth century; among the innovative features of the building was the new relationship that thearchitect wanted to establish between the overall architectural space and those who would use and even enjoy it; divided into three separate wings according to the different educational activities, this building met the needs of an architecture that, like design, had to come to be functional, in coexistence with the city and practical needs and where no part would be more important than the others: here, for example, the idea of a main façade was eliminated, as every building of previous periods up to that time had been required to have, and each side constituted at that point a façade no less important than the others.

The Bauhaus style and experience would represent a milestone in the birth and development of modern architecture and contemporary design and the introduction of new aesthetic canons. One of the fundamental programmatic points, as mentioned above, was the cancellation of the distinction between artist and craftsman; students were offered basic craft training to be achieved in workshops and places of experimentation and work, which would serve to create objects with the soul of works of art.

Characteristic of the Bauhaus is a geometric, severe but elegant style, made with great economy of means that affirmed the school’s founding principles: essentiality, modernity, equality, attention to color and form, which “follows function.” Although in reality the works produced were richly diverse, aminimalist aesthetic became widespread, radically opposed to the rich decorativism of the Art Deco, which had just preceded it.

Examples are, in the field of graphic design and communication, the birth of Herbert Bayer’s font, devoid of capital letters, minimal geometric to ensure better legibility; and in furniture design, the use of metal tubing in the structure of chairs and tables, light, easily transportable and mass-produced, which met all the design requirements of the school: the components of the objects, arranged with a clarity made their purpose and use clear. Starting with the research that Marcel Breuer did with it. His “Wassily” armchair is an elegant fusion of curved stainless steel tubes stacked on top of each other with taut rectangular fabric panels, floating like geometric shapes in space. It will indeed dominate the geometric idea, in painting as in ceramics, as well as in interior decoration and trim, sculpture and weaving patterns. By eliminating ornaments, a new modern and international spirit was expressed.

Among others, Paul Klee who was one of the Bauhaus’s most talented painters, combined delicate geometric forms and gradations of color(Red Balloon, 1922) hand in hand with the extraordinary formal innovation brought forth by Vasily Kandinsky(Yellow-Red-Blue, 1925) and in photography by Moholy-Nagy, who experimented with a technique of shooting directly on photosensitive paper without a camera. Bauhaus works demonstrate a technological and creative side in their efforts to explore the properties and possibilities of different artistic media.

|

| Bauhaus. Origins, development and main exponents of the school |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.