Baroque Sculpture. Origins, development, artists and masterpieces

The Counter-Reformation had emphasized the need for art that on the one hand would call the faithful back to Catholic doctrine and on the other affirm the primacy of the Catholic religion against the Protestant Reformation. Both of these tendencies, in the first decades of the seventeenth century, found their convergence and resulted in the Baroque language: to bring the faithful back to the canons of the Church of Rome also meant to engage them emotionally in a strong way, to amaze them, and to affirm the primacy of the Catholic religion meant to communicate the power and triumph of the Church. This led to a style of very strong impact and characterized by considerable virtuosity dictated precisely by the desire to amaze.

The term itself, baroque, contains within itself, we might say, the essence of the art that was produced in this era: it may in fact derive from the Spanish term barrueco (or from its Portuguese counterpart barroco), by which is meant the scaramazza pearl, that is, a pearl with an irregular shape. This term, which originated in a derogatory sense in the context of late eighteenth-century historiography, precisely to indicate an apparently empty and excessively extravagant art, was then taken up again, but in a positive sense this time, at the end of the nineteenth century, when thanks to the work of the German scholar Heinrich Wölfflin, Baroque poetics began to be reevaluated and to be analyzed more thoroughly also on the basis of the social and cultural context that produced it.

Characteristics and developments of Baroque sculpture

One of the distinguishing features of Baroque art was certainly the cult of the image, born in opposition to the typically Lutheran tendency whereby the work of art was considered a useless display, a vanity, an ostentation. This is why the Catholic Church, in the Baroque era, multiplied artistic commissions, according to the idea that the more a work amazed to the point of almost intimidating the observer, the more it struck a chord. Art, with the Baroque, became an instrument of persuasion and propaganda: in Italy the greatest commissions fell to the Church, but soon the Baroque also spread throughout Europe and even to the rest of the world, especially toLatin America, where the Church was at the time carrying out its work of evangelization. Thus a highly theatrical art was born, where the image was seen almost as a divine manifestation, and soon the virtuoso language elaborated by artists for the Church began to be particularly appreciated by private patrons as well, for in the midst of the age of absolutism, Baroque art performed the same function of triumphal celebration for states as it did for the Church.

Baroque tendencies in both painting and sculpture, however, were anticipated by some artists who trained in the late Mannerist milieu, and in this regard it is worth noting that the Baroque was often seen as a kind of ideal continuation of Mannerism whose virtuosity it reproposed, albeit with a different meaning. Mannerist virtuosity was in fact a reaction to Renaissance order and rigor, which, at a time of great unrest, were concepts that artists wanted to undermine and upset, while Baroque virtuosity stemmed from the search for an art to effect that would appeal to observers.

Sculptors who anticipated the Baroque.

Among the earliest sculptors who, somewhere between late Mannerism and new trends, saw their art flourish at a time when the Baroque was already establishing itself, one can count Pietro Tacca (Carrara, 1577 - Florence, 1640). A pupil of Giambologna and active at the Medici court, he exercised his taste for the bizarre in a number of fountains made for the grand dukes of Tuscany (such as the fountain made in 1629 in Florence’s Piazza Santissima Annunziata) in which various motifs drawn from the animal and plant world found a place, in addition to those extravagant fantastic figures that abounded even in the Baroque era.

Tacca’s art, which often took on explicit celebratory intentions in the monuments made to celebrate the grandeur and decorum of his powerful patrons of the Carrarese sculptor, found precisely in the genre of the equestrian monument its peaks of virtuosity. Pietro Tacca, in fact, was the first sculptor in the history of art to create an equestrian monument with a rearing horse on its two hind legs: the monument to Philip IV of Spain, completed in 1634 (Madrid, Plaza de Oriente). Pietro Tacca’s interest in science also contributed to this achievement: the sculptor had become friends with Galileo Galilei, who, according to tradition, helped the artist in studying the statics of the monument. Despite the fact that the Church exercised a strong control over science (and an example of this control is the trial suffered by Galileo Galilei himself), scientific research was not discouraged, except where the scientists’ positions were in open conflict with the dictates of the Church, so much so that those sciences that could be freely practiced (such as biology) experienced considerable progress during the seventeenth century.

To the same generation as Pietro Tacca belonged two sculptors who, though of different origins, both worked in Rome in the early seventeenth century: Stefano Maderno (Bissone, 1576 - Rome, 1636) and Francesco Mochi (Montevarchi 1580 - Rome 1654). Maderno, a native of Canton Ticino, was a sculptor characterized by simple and pathetic manners still typically Counter-Reformation. His quest for pathos that led to a natural emotional involvement of the viewer is seen as a prelude to the Baroque sculptors’ quests for emotionality and drama(Santa Cecilia, 1600, Rome, Santa Cecilia in Trastevere).

The Tuscan Mochi went even further: an author, like Pietro Tacca, of equestrian monuments, he produced sculpture characterized by a vivid dynamism that found fulfillment in the twisting of the bodies of the figures, the sensation of movement, and theatrical gestures, as in the Vergine Annunciata in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Orvieto. All with a marked interest in the representation of feelings. Francesco Mochi was probably the artist who best anticipated the novelties of Baroque art.

Leading Baroque sculptors

The artist, however, who was most revolutionary and with whom the transition to Baroque instances in sculpture was fully realized, was Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples, 1598 - Rome, 1680): the son of a late Mannerist Tuscan sculptor, Pietro Bernini, he was a precocious talent who trained himself by studying ancient marbles (which in his youth he was able to imitate so well that it led him to consider what is now considered his first work, namely the Amalean Goat, a sculpture from the Hellenistic period), but also the masters of the mature Renaissance (the reference for sculptors was still Michelangelo), and he also looked with interest at contemporary painters.

Having come into the good graces of the Borghese family, with one of his first works, namely the David (1623-1624, Rome, Galleria Borghese), Bernini reveals one of the characteristics of his Baroque poetics: the great dynamism that connotes the statue and makes it assume a totally original pose is functional in capturing a precise moment in the action, which is not a moment chosen at random, but is precisely the culminating moment, that is, the very instant in which the stone is about to be thrown by the hand of the protagonist. The character caught in the instantaneousness of a moment that lasts a fraction of a second, which is precisely why it must be represented from a privileged point of view, namely the frontal one. This way of proceeding appears different from that of Mannerist virtuosity, which instead presupposed several points of view from which to fully enjoy the dynamism of the realization. A dynamism that also constitutes one of the specific features of Bernini’s poetics and is perceptible in many of his works, which are developed in sinuous and tortuous lines (a typical example isApollo and Daphne, 1622-1625, Rome, Galleria Borghese): the curved line is one of the foundations of Baroque art.

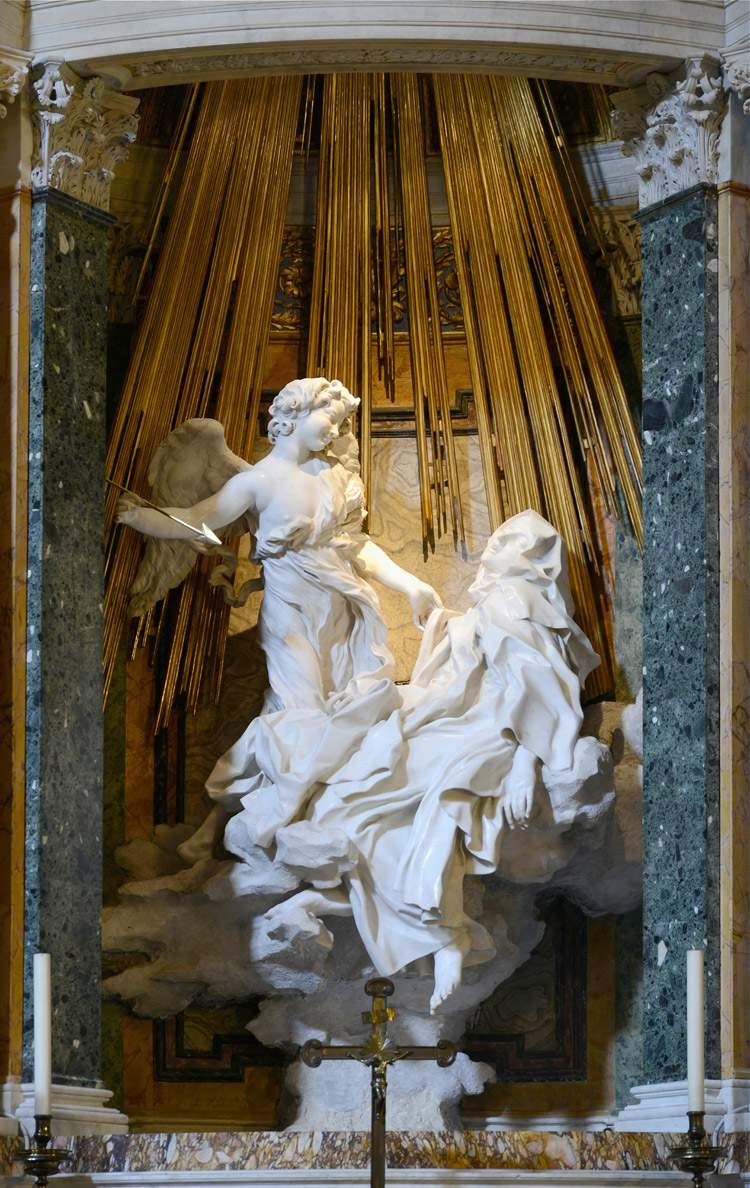

The search for drama and involvement, as it is easy to imagine, was practiced by Bernini especially in works with religious subjects: in particular, with his Ecstasy of Saint Theresa (1647-1652, Rome, Santa Maria della Vittoria), Bernini was able to achieve a very intense representation, which cannot leave the viewer indifferent, also because it was developed according to a deliberately and openly theatrical layout (the members of the commissioning family, the Cornaro family, are portrayed while they watch the scene from a balustrade). Theatricality, which after all is one of the fundamental components of Baroque art, reaches its zenith in this work by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Another of the most important features of Baroque poetics was the contamination between different art forms, especially the three main ones, namely painting, sculpture andarchitecture: according to this principle, typical elements of one art form were to mix with each other. The highest moment in this sense was reached by Bernini in his St. Peter’s baldachin (1623-1633, Rome, St. Peter’s), a monumental work halfway between sculpture and architecture, rich, however, in decorations with a marked pictorial sensibility: it was a structure intended to surmount the tomb of St. Peter, characterized by a layout that referred to a centuries-old tradition but, of course, extensively revisited and updated according to the novelties and the all-Baroque inspiration of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Moreover, it was a work with a strong celebratory impact: the same component of celebratory solemnity typical of Baroque art was pursued by Bernini in his wide-ranging works, among which the funeral monument of Pope Urban VIII, born Maffeo Barberini, the pontiff who procured Bernini several commissions and helped make him the most in vogue and influential sculptor in seventeenth-century Rome, is fully included. Bernini’s monument (1628-1647, Rome, St. Peter’s) is one of those highly spectacular works that probably best give concrete evidence of the Church’s desire to assert its triumph.

Bernini’s genius was not replicated by any of his successors, who mostly repeated the formulas invented by the master. However, there was no shortage of artists endowed with original or interesting ideas: among them, the greatest were Alessandro Algardi (Bologna, 1598 - Rome, 1654) and Domenico Guidi (Torano di Carrara, 1625 - Rome, 1701). On both sculptors Bernini’s ascendancy had a considerable influence. Each of them, however, developed a specific trait of Baroque art. Alessandro Algardi proposed highly celebratory monuments that were characterized, however, by more composed and almost idealized tones than those of Bernini (funeral monument of Leo XI, 1634-1644, Rome, St. Peter’s). Domenico Guidi (who was a collaborator of Algardi’s) instead developed a particularly charged drama that found its peaks in works characterized by extremely free and dynamic lines, as in the marble altarpiece of the church of Sant’Agnese in Agone in Rome.

|

| Baroque Sculpture. Origins, development, artists and masterpieces |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.