Artemisia Gentileschi (Rome, 1593 - Naples, after 1653), the daughter of the Tuscan-born painter Orazio Gentileschi (Pisa, 1563 - London, 1639), himself a famous painter and friend of Caravaggio, was a great artist who was able to reveal her talent and succeed in a society that tended to be closed, in which women did not have much chance to emerge. Notorious is the sad affair of the violence she suffered, which according to some readings, particularly those of a feminist bent, spilled over into her art, which became very brutal precisely because of her background (although in reality particularly truculent or violent themes are typical of seventeenth-century art: read an in-depth study on the subject in relation to Artemisia’s painting here). Artemisia moved within the Caravaggesque framework but proposed a very original art, with masterpieces of great realism and often also of marked sensuality.

Artemisia was <firstborn

The best known episode in the life of Artemisia Gentileschi is that of the violence she suffered at the age of eighteen years not yet completed at the hands of Agostino Tassi (Ponzano Romano, 1580 - Rome, 1644), a painter of good standing, friend of Orazio Gentileschi and his collaborator: the rape was followed by a trial, and the acts of the trial have reached us in their entirety, a condition that has allowed us not only to understand how the affair went, but, through the testimonies and interrogations, it is also possible to derive many details about the lives of the artists involved (for example, thanks to some witnesses it has been possible to reconstruct in more detail the relationship between Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi). Agostino Tassi was a painter of undisputed talent but of less than exemplary conduct and with some criminal records. The artist had fallen in love with his friend’s daughter, and according to Artemisia’s own account, on May 9, 1611, the girl was sexually assaulted by the painter (moreover, during the trial Artemisia recounts the violence with great rawness and great detail). Rape at the time was a crime, and in the specific case it was all the more serious because of the fact that Artemisia had been deflowered during the violence, but unfortunately, according to the mentality of the time, rape was also considered infamous for the woman who suffered it: however, the dishonor could be partly repaired by marriage. Thus, initially Agostino Tassi promised Artemisia to marry her (although some speculate that the promise was intended to avoid condemnation). Artemisia then believed Agostino’s promises and a relationship was born between the two that lasted several months, until it was discovered that in fact Agostino Tassi was already married. Tassi was therefore denounced by Orazio Gentileschi, and the trial lasted from March to November 1612 (Artemisia also had to undergo torture because, unfortunately, the justice of the time believed that during torture those being interrogated told the truth), and the affair ended with a sentence against Agostino Tassi, who was forced to choose between five years of hard labor on the papal galleys and exile from Rome. The painter chose exile, although then, a few years later, he was able to return to Rome because he was a well-known painter and enjoyed the support of the powerful. Following the trial Orazio Gentileschi arranged a marriage for his daughter to a young Florentine painter of low status, Pierantonio Stiattesi, nine years older than Artemisia, with whom the young woman moved to Florence, ending the most painful interlude of her life.

|

| Simon Vouet, Portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi (c. 1623; oil on canvas, 90 x 71 cm; Pisa, Palazzo Blu) |

Artemisia Gentileschi asce in Rome on July 8 by the great painter Orazio Gentileschi and Prudenzia Montoni. Around 1606 she began her artistic apprenticeship in her father’s workshop. In about 1610 he executed his first known work, Susanna and the Old Men, currently preserved in Pommersfelden, Germany. Although the canvas is signed and dated, it is the subject of debate because the girl may have been decisively helped by Horace. In 1611 Artemisia suffered violence at the hands of painter Agostino Tassi, a colleague of her father’s. The following year the trial against Agostino Tassi opened, and by the end of the year he was sentenced to spend five years in the papal galleys or alternatively to perpetual exile from Rome. Tassi chooses exile but a few years later will be able to return to Rome. In November, Artemisia married Pierantonio Stiattesi, a modest Florentine artist. In 1614, she moved to Florence where she enjoyed the protection of Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici and his wife, Christina of Lorraine. Around 1615 she executed theAllegory of the Inclination at Casa Buonarroti for her friend Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger, and the Conversion of Magdalene at Palazzo Pitti. In 1616 she was admitted to the Accademia del Disegno in Florence, where she remained enrolled until 1620, when she left Florence and returned to Rome.

In 1622 she executed the Ritratto di gonfaloniere (Portrait of a Gonfalonier ) preserved in Bologna, at the Palazzo d’Accursio. In 1627 he moved to Venice, and in 1630 there is a record of his moving again, this time to Naples, where in the same year he executed theAnnunciation now in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte. He became one of the most important artistic personalities in the Neapolitan city although he repeatedly expressed a desire to return to Rome. About the same year he executed the famous Self-Portrait in painting.

In 1635 he executed some works for Pozzuoli Cathedral, and the following year, 1636, he moved to London joining his father Horace, who had been called to England by King Charles I at the suggestion of the Duke of Buckingham. Together with his father he worked on the Triumph of Peace and the Arts for the Queen’s House in Greenwich (now preserved in London at Marlborough House). In 1639 Horace died in London, and Artemisia, who had been close to him in his last days, returned to Naples: she did not move from the Campania city for the rest of her days. However, very little is known about the last years of his activity. In 1649 he executed some works for Antonio Ruffo, a Sicilian art collector who was among his best patrons during his stay in Naples. After 1653 the artist disappeared in Naples, but we do not know the exact date of his death.

|

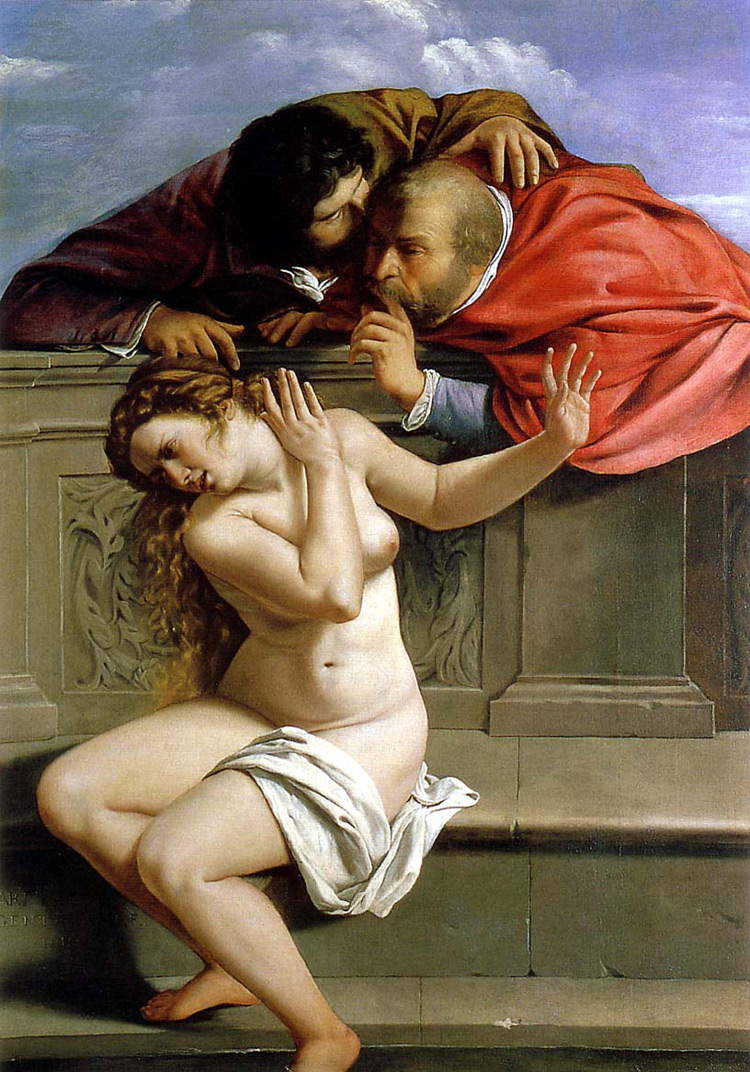

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Old Men (1610; oil on canvas, 170 x 119 cm; Pommersfelden, Kunstsammlungen Graf von Schönborn) |

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes (1617; oil on canvas, 158.8 x 125.5 cm; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte) |

Artemisia Gentileschi’s most famous works are those she painted in the early part of her career. The first work referable to her, Susanna and the Vecchioni, is particularly controversial because we do not know exactly when it was made (some say it is a 1610 work and some consider it a later work, some attribute it to Artemisia alone and some consider it the result of a collaboration between father and daughter). It is difficult to shed full light on this painting, although it has an inscription bearing Artemisia Gentileschi’s signature and the date 1610: there are those who argue that this was a ruse used by the father, who allegedly antidated the painting to show how good his daughter was already at a young age. It is clear from this work the extent to which the young woman is affected by her father’s lesson, but even from her earliest years she nonetheless attempts to break free from Horace, proposing her own reading of the biblical fact, particularly by accentuating the sorrowful aspect of the story, with Susanna despairing and recoiling in horror (note the realism of her expression). This is a juvenile work, but a very interesting one, because it manages to emotionally engage and manages to convey all the sense of disgust and at the same time all the concern and all the outrage of the protagonist. While this is a depiction of a sad affair, of a violation, Judith Beheading Holofernes has been interpreted by feminist critics as the young woman’s revenge on the one who violated her. There are two versions of this work, one made around 1612 and kept at the National Museum of Capodimonte in Naples, and the other, similar but with the characters dressed more sumptuously, kept in Florence at the Uffizi (the Florentine lversion was commissioned by Cosimo II de’ Medici when the young woman moved to Florence and in fact in its clothes reflects the Florentine taste of the time). If the Susanna was already a very strong work, this one is even more so: it is a brutal work, demonstrating an incredible charge of violence, with a Judith pouncing on her rival to cut off his head. Note the blood gushing profusely on the mattress, and in the Florentine version we can also see the splattering of blood from the wound, and note also the detail of the handmaiden, who according to the biblical account did not participate in the killing, and here instead, for the first time, is depicted helping Judith to hold Holofernes still and motionless; finally, another detail that strikes the viewer very strongly is the expression of Holofernes. It is a painting of clear Caravaggesque influence (it echoes Caravaggio’s counterpart painting preserved today in Rome, so much so that it is conceivable that Artemisia knew Caravaggio’s work: however, compared to the latter’s painting Artemisia’s is much more violent.

Artemisia’s style would change radically over the course of her career: in the Florentine period it became much more elegant and less violent, leading up to her years in Venice, when Artemisia’s manner approached that of the great masters who worked in the lagoon, such as Tintoretto and Veronese. Particularly illustrative is the painting Esther and Ahasuerus: a painting that well combines the painter’s Caravaggesque training with the theatricality and sumptuousness of Venetian representations whose theme was events from the Bible. And this is perhaps one of Artemisia Gentileschi’s most sumptuous paintings, just look at the rich garments of the characters, Esther’s gilded dress, her crown, the fine white sleeve decorations, the blue sash, Ahasuerus’s robe (a seventeenth-century robe with white and green puffed sleeves), the feathered hat, the beautiful boots, and the ornate throne.

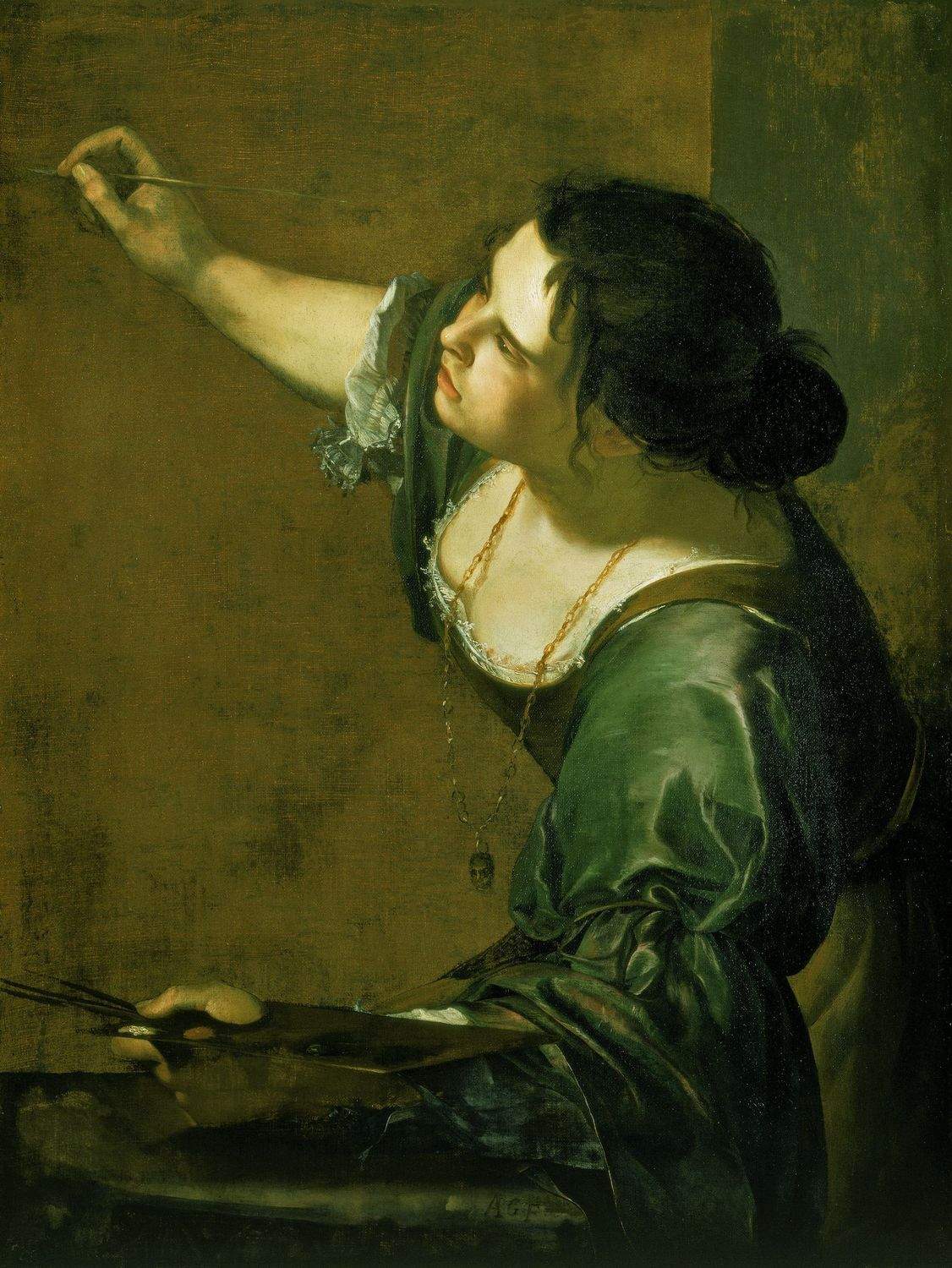

Self-portraits also abound in Artemisia’s production, such as the portrait in painting, a masterpiece that dates from about 1630 and is preserved in London’s Kensington Palace. It is a very original painting, because Artemisia portrays herself in three-quarter view while she is working: usually painters portrayed themselves frontally or in profile, and mostly posed, and she decided instead to break with tradition, painting herself with her working tools in her hands, her brushes and palette, while she is executing a painting. In order to represent herself in this pose, she had had to resort to a game of mirrors, and the result of this depiction strikes the viewer, who would not expect a self-portrait in these terms to be very realistic, with the artist having her sleeves rolled up to her elbow. In the self-portrait, Artemisia, as an allegory of Painting, wears a gold chain around her neck with a pendant in the shape of a mask: to understand why some of the attributes are used, we must refer to Cesare Ripa’sIconology, a treatise describing the attributes that poets painters and sculptors had to use to represent all abstract concepts (such as virtues and vices), and among these concepts was that of painting, which, according to Cesare Ripa, had to be represented as a beautiful woman, black-haired, with a gold chain from which hung a pendant in the shape of a mask, with a paintbrush in one hand and a palette in another, as well as an iridescent robe. The mask, as Cesare Ripa himself explains, is a symbol of imitation, and imitation is “conjoined with painting inseparably,” as Ripa wrote. On Artemisia we also suggest you read the review of the exhibition held in Rome, at Palazzo Braschi, between 2016 and 2017.

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes (c. 1616-1617; oil on canvas, 146.5 x 108 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Esther and Ahasuerus (1628-1635; oil on canvas, 208 x 273 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait in Painting (1638-1639; oil on canvas, 98.6 x 75.2 cm; London, Kensington Palace) |

Artemisia’s catalog is not very extensive: few of her paintings are known. Works by Artemisia Gentileschi can be found in major Italian museums. The Uffizi conserves the second version of Judith Beheading Holofernes, while, also in Florence, the Pitti Palace houses two important works from the Florentine period, namely the Conversion of Magdalene and Judith with a Handmaid, and Casa Buonarroti conserves theAllegory of Inclination, executed for the place that still houses it today. In Pisa, in the collection of Palazzo Blu,one can admire Clio, a depiction of the muse of history, while the collections of Palazzo d’Accursio in Bologna house the splendid Ritratto di gonfaloniere. In Rome, his works are at the Galleria Spada (the Saint Cecilia and the youthful Madonna and Child), while to get to know the Artemisia of the Neapolitan period, the paintings executed for the Pozzuoli Cathedral between 1636 and 1637 are a must-see (the Saint Gennaro in the amphitheater of Pozzuoli, Saints Proculus and Nicea, and theAdoration of the Magi).

Abroad, the Graf von Schönborn collection in Pommersfelden preserves the first work referable to Artemisia Gentileschi, namely Susanna and the Old Men: Other works of hers can be found at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest(Jael and Sisara of 1620), the Detroit Institute of Arts(Judith with Handmaid of 1625-1627), the Metropolitan in New York(Esther and Ahasuerus of c. 1628-1635), the Prado in Madrid (the Birth of the Baptist of c. 1633-1635), at Kensington Palace in Lonra(Self-Portrait in Painting, 1638-1639), and, also in London, at Marlborough House(Allegory of Peace and the Arts under the English Crown, 1638-1639, a work created together with Orazio Gentileschi). Three works by Artemisia have recently appeared on the market, purchased by as many foreign museums: a Self-portrait as St. Catherine of Alexandria that became part of the collections of the National Gallery in London, a Lucretia, bought in 2021 by the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and a St. Catherine of Alexandria that was instead acquired by the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm.

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, life and works of the great seventeenth-century artist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.