Art Nouveau: international origins and development in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

Art Nouveau is a decorative art style of international scope that developed out of the Secessions and spread widely throughout Europe and the United States in the late 19th and first decades of the 20th century. It was a deliberate attempt to create a new style, free from the imitative historicism and variety of other styles that dominated much of the 19th century, which affected painting and sculpture and all the more architecture and applied arts, graphics and design in the search for new beauty among artifacts and industrial products. From interior and urban decoration to furniture and textiles, glassware and jewelry, lighting to funerary art and advertising.

The name “Art Nouveau” appeared in anti-academic art circles in Belgium in 1884 and was also used in France, later varied in the different countries where it spread: in Italy “Stile Floreale or Liberty”, in Germany “Jugendstil”, in Austria “Sezessionstil”, in Spain “Modernism”, in England it was called "Modern Style" and in Scotland “Glasgow School”, while in the United States it retained the name Art Nouveau. It developed most rapidly in countries or regions claiming greater cultural autonomy and in those that were experiencing economic prosperity, and was dominant in new areas built to cope with increasing urbanization in the late nineteenth century to disappear almost entirely during World War I.

The distinctive ornamental feature of Art Nouveau is the asymmetrical wavy line based on a naturalistic plant and animal repertoire, often taking the form of flower stems and buds, tendrils, insect wings, and other sinuous natural forms. Artists were inspired both by organic and fluid forms and also by more geometric ones, accentuating the emphasis in drawing on linear contours that took precedence over color.

In the graphic arts, the decorative effect of line is indeed preponderant and recognizable over all other pictorial elements. Just as inarchitecture and other plastic arts, three-dimensional form traces an organic, linear rhythm, creating a correspondence between functional structure and ornament. Especially in architectural interiors, this conception of ornament combined with the function of the elements emerged, as opposed to the traditional architectural values of rigor and clarity of structure, whereby, for example, columns, beams and windows in addition to their own function could draw as a whole a total organic interior vision.

The dominant academic system in art education from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century had hitherto held the belief that media such as painting and sculpture were superior to crafts such as furniture and object design. Art Nouveau artists sought to overturn that belief, pushing a new orientation of taste and aspiring to total works of art, according to the concept so expressed in German Gesamtkunstwerk, which had been popular since 1849 and which describes the combination of different artistic expressions into a single cohesive whole, where each element contributes harmoniously into the whole. Art Nouveau minimized the gap between the so-called fine and applied arts, giving impetus to Modernism, and raging until about 1910, thanks to a large number of artists, architects, and designers who paved the way for the development of Art Deco in the 1920s, only to revive again, refashioned, in certain trends in the 1960s and 1970s.

Origins and international development of Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau, literally “New Art,” has an English antecedent around 1880 in the British Arts and Crafts (“Arts and Crafts”) movement, which established the importance of a vital style in the applied arts, which arose in reaction to the decorative arts in particular of the Victorian era and which advocated a reassessment of quality craftsmanship against the overwhelming industrial production and the resulting decline in taste in the second half of the nineteenth century. Style Art Nouveau absorbed at the same time the influence of Japanese painting, graphics, and woodcuts, which determined the taste for asymmetry, bold cuts in composition, speed of execution, the collaboration that was seen between art and craft, and generally a push in painting toward a stylization of figures and a decorative conception of form, often linked to symbolic motifs. These were all key elements of the Art Nouveau style, such as floral and bulbous forms, “whiplash” curves, and strong contours along with the sensual characteristic of figures, especially women, languid and mysterious.

The phenomenon of Japonism had influenced many European artists in the 1880s and 1890s. Among them was the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt (Baumgarten, 1862 - Vienna, 1918), considered an innovative painter of Art Nouveau fame and a master of Modernism, who as a founding member of the Vienna Secession rejected the principles of academic painting and determined an imagery of sophisticated but depthless forms, traceable to Japanese two-dimensionality. Linearity and curved motifs borrowed from nature were reused in a “logical” way and became proper graphic clichés. However, it is difficult to identify the first artwork or works that officially launched the Art Nouveau style. The term was coined by the Belgian periodical L’Art Moderne to describe the work of the group of artists Les Vingt (twenty Belgian artists who, analogous to what was happening in Paris with the Salon of Independent Artists rejected by the official exhibition, inaugurated the Salon of the XX) and in Paris by Siegfried Bing, an art dealer who in 1895 named his gallery precisely “L’Art Nouveau.” Some art historians argue that the molded, flowing lines and floral backgrounds found in the paintings of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin or even the graphics of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, such as Moulin Rouge: La Goulue (1891), represent the birth of Art Nouveau, however much of the current’s origin and development is due to architecture and the decorative arts. One can baptize as “Art Nouveau” the first use of certain materials such as iron by Belgian architect Victor Horta (Ghent, 1861 - Brussels, 1947) for the houses of the Brussels bourgeoisie around 1893. The period of greatest attestation and splendor was witnessed by the 1897 Tervueren Exhibition in Brussels; the Expositions Universelles of 1889 and 1900 in Paris; the 1902 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art in Turin; and the 1909Exposition International de l’Est de la France in Nancy.

Many names of artists, architects, and designers worked in the Art Nouveau style, maintaining, despite the differences given by the wide international spread, some common characteristic features, such as the ornamental line. The fluidity of lines, asymmetrical compositions without geometric perspective, and delicate shades of color created a new ornamental vocabulary.

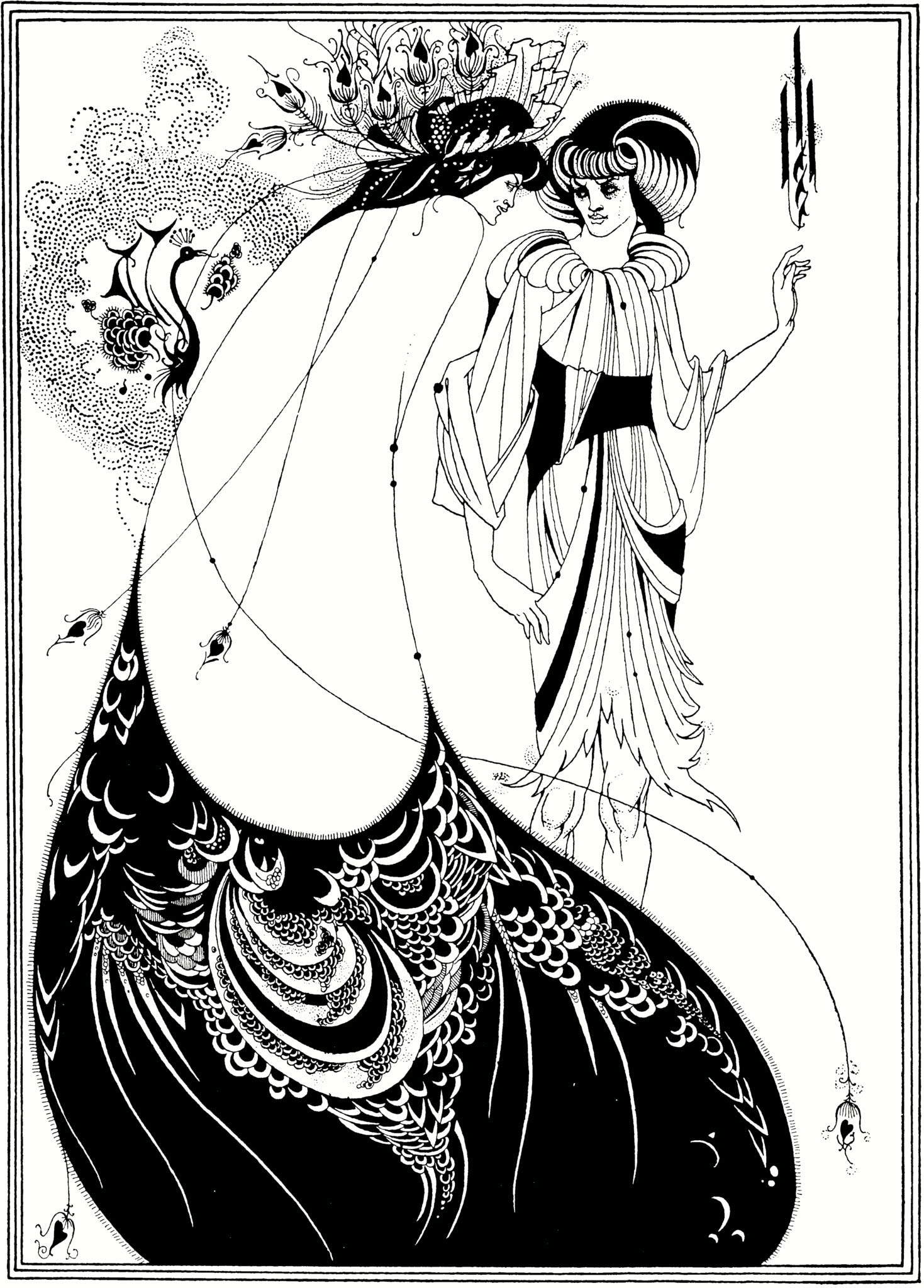

Among the exponents in painting, in addition to Klimt, was Englishman Aubrey Beardsley (Brighton, 1872 - Menton, 1898), who created in his short career a series of graphics/posters that used graceful, rhythmic lines. Beardsley’s highly decorative prints, such as The Peacock Skirt (1894), in its flattened rendering of form represent an even more direct link between Art Nouveau and Japanese prints. But Art Nouveau painters proper were few and far between: Klimt counted virtually no students or followers, and among the French Victor Prouvé (Nancy, 1858 - Sétif, 1943) was known equally as a sculptor and furniture designer.

Others include a varied roster of influential interpreters representing the style: starting with Belgians Henry van de Velde (Antwerp, 1863 - Oberägeri, 1957) and Victor Horta himself, who designed theHôtel Tassel or “Tassel House,” considered precisely the first Art Nouveau building, whose extremely sinuous structures influenced French architect Hector Guimard (Lyon,1867 - New York, 1942) , another decisive figure, author in 1900 of the Entrances to the Paris subway stations; Scottish architect and graphic designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh (Glasgow, 1868 - London, 1928) , who asserted a predominantly geometric line and particularly influenced the Austrian Sezessionstil; French designers Louis Majorelle (Toul, 1859 - Nancy, 1926), of iron furniture and objects, and René Lalique (Ay, 1860 - Paris, 1945), of glass and jewelry; Czechoslovakian graphic designer Alfons Mucha (IvanÄice, 1860 - Prague, 1939) known for his work for advertising posters; American glassmaker Louis Comfort Tiffany (New York, 1848 - 1933), American architect Louis Henry Sullivan (Boston, 1856 - Chicago, 1924), who used Art Nouveau iron by depicting plants to decorate his traditionally structured buildings; and Spanish architect and sculptor Antoni Gaudí (Reus, 1852 - Barcelona, 1926) , one of the movement’s most original artists and the greatest exponent of Catalan Modernism, who went beyond the use of line to transform buildings into curved, brightly colored, organic constructions. He is credited with some of the most exemplary constructions: in Barcelona, the benches in Parc Güell are designed to align with the human spine, and the balconies of Casa Milà (“La Pedrera”) represent abstractions of leaves and blades of grass. It was this inspiration that separated Gaudí from other styles of the time and distinguished him as a member of Art Nouveau. His most famous work, the great temple La Sagrada Familia, is still under construction as of 1882.

In the European development of this style, the relationship with industry and the use of new techniques and new materials was a decisive stimulus for the search for stylistic solutions and for the emergence of a new conception of unity between design and product: between workmanship of the material and functionality of the object in craftsmanship, between interior and exterior in architecture. Magazines, illustrated and with contributions and photographs, played a decisive role. Among the first was the English magazine The Studio, which also appeared in French from 1893 and organized competitions for creations in the applied arts. The aforementioned L’art Moderne in Brussels and Van Nu en Straks, which show the avant-garde role Belgium played in the development of Art Nouveau. In Vienna Ver Sacrum (1898- 1903), the official organ of the Secession presided over by Klimt to which the student architects of Otto Wagner, Joseph M. Olbrich and Josef Hoffmann; in Munich Jugend (which will give rise to the term Jugendstil) around which gathered artists such as Hermann Obrist and Otto Eckmann who worked on decorative plant motifs; in Barcelona Joventut magazine and in France, through the Parisian Art et décoration of 1897 and L’Art décoratif, where at the same time Siegfried Bing organized also a “first Salon of Art nouveau” in which he presented paintings by Eugène Carrière, Maurice Denis, and Fernand Knopff, sculptures by Auguste Rodin, glassware by Émile Gallé and Tiffany, jewelry by Lalique, posters by Beardsley and Mackintosh, and in 1896 the first Paris exhibition of Edvard Munch.

The height of enthusiasm for Art Nouveau was reached around that 1902, the year in which, as mentioned earlier, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art, also referred to as the First International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art, was held in Turin, Italy. Major European examples of architecture, furniture and applied arts and graphics were exhibited at the Valentino Park. It was the first overview of the style known as Art Nouveau, of which Turin was to be recognized as the capital, and named after Arthur Lasemby Liberty’s London warehouses that had specialized in the sale of floral-flavored fabrics and furnishings since 1895. Liberty & Co. was the leading distributor of the style’s objects in Britain and Italy, where its name became synonymous with the style.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the style also known as "Floral," precisely, raged in all artistic circles. Examples of the spread can be felt in the prevalence of the line in the decorative sense alongside the strong influences of the more symbolist currents of European Art Nouveau and in particular of the Viennese Secession and Klimt, beginning with works such as Leonardo Bistolfi’s manifesto just for the Turin Exposition, a sculptor also known for his funerary monuments, and in the architectural work of Raimondo D’Aronco, who of the 1902 Exposition created the pavilions.

Other Italian representatives of the brief Italian season of Art Nouveau include architect and engineer Pietro Fenoglio, who in the same year as the Exposition signed two works in Turin that constitute two important Italian examples of the new style: Villa Scott and Casa Fenoglio-La Fleur. And colleagues Ernesto Basile, Giuseppe Sommaruga, Gino Coppedè, or for pictorial, decorative, ceramic and scenic work Galileo Chini, the so-called Italian Klimt.

Legacy of Art Nouveau

After 1910, the Art Nouveau style waned, to reassert itself as a decisive style with historical significance in the design of the 1960s, both through major exhibitions held in New York (1959), Paris (1960), and London (1966) and in the work of other artists who, drawing on the linear, free-form qualities of the historic style, countered the limiting, impersonal, and increasingly minimal aesthetic that prevailed in the graphic arts in the later 1970s. A reappraisal of style what was branded by some art critics as a short-lived passing trend is now understood as an expression of the design method, spirit, and intellectual thinking of a certain time frame, centered around 1900.

Where to see Art Nouveau works

In addition to the graphic and visual artworks scattered in numerous museums around the world, Art Nouveau can be seen through its architecture in urban centers such as Paris, Brussels, Glasgow, Turin, Barcelona, Antwerp, and Vienna, as well as in smaller cities such as Nancy and Darmstadt, along with Eastern European locations such as Riga, Prague, and Budapest.

Today it is still recognizable in diverse structures, from small townhouses to large institutional and commercial buildings of multiple expressions. Many buildings incorporate prodigious use of terracotta and colored tiles. Other Art Nouveau structures, particularly in France and Belgium, show the technological possibilities of an iron structure joined by glass panels.

In many parts of Europe, local stone such as yellow limestone or a rocky, irregular rural aesthetic with wood trim characterized Art Nouveau residential architecture. And in several cases a typical sculptural white stucco cladding was used, particularly on buildings used for exhibitions, such as the pavilions of the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris and the Secession Palace in Vienna. Even in the United States, the plant forms that adorn Louis Sullivan’s skyscrapers such as the Wainwright Building and the Chicago Stock Exchange are often counted among the best examples of Art Nouveau’s broad architectural scope.

In addition, numerous monuments are recognized among UNESCO World Heritage Sites, such as the Principal Townhouses by architect Victor Horta in Brussels and Saint-Gilles, and seven buildings by Antoni Gaudí between in Barcelona and Santa Coloma de Cervelló. One of the European cities with the largest number of Art Nouveau buildings recognized by UNESCO is Riga in Latvia, where the Riga Art Nouveau Centre is also located.

For all the numerous testimonies in Europe, you can find your way around by consulting the Réseau Art Nouveau Network (RANN) , which has been bringing together cities and institutions with a rich Art Nouveau heritage in a first European cooperation network since 1999.

|

| Art Nouveau: international origins and development in the late 19th and early 20th centuries |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.