Antonio Ligabue: the painter, life, works

He is among the most beloved painters of the twentieth century: we are talking about Antonio Ligabue (Zurich, 1899 - Gualtieri, 1965), considered the naïf painter par excellence (although, as we shall see, it is a somewhat “narrow” definition). His works continue to fascinate tens of thousands of people, his extraordinary life has been recounted in television dramas (the one with Flavio Bucci as the artist is very famous), as well as in films, even recently (for example, the feature film with Elio Germano playing the painter), and his very existence is seen almost as the symbol of a revenge that occurred thanks to art, since, for most of his life, Ligabue did not really have a good time, far from it. In fact, his life has been very difficult.

Today, Ligabue is such a popular painter with the public that he is featured in numerous exhibitions that are organized throughout Italy. Indeed, Ligabue was a very original painter, lacking academic training, capable of totally identifying himself with the product of his hands (whether it was paintings or sculptures: Ligabue was in fact also a sculptor), as well as of moving the viewer and capturing him by dragging him with him into his visionary world, made up of ferocious animals, memories of Switzerland (his homeland), views of the Emilian countryside and much more. Through his art, however, Ligabue was able to sublimate his vicissitudes by asserting his own personality, despite the fact that at first “el Matt” (this was the nickname given to him by the inhabitants of Gualtieri, his adopted town) was not understood by his contemporaries, who on the contrary mistook him for a madman and often rejected even his paintings. It was not until the end of his career, thanks mainly to the work of critic Renato Marino Mazzacurati, that the doors of success opened wide for him. For the artist it was an ephemeral success, as he died a few years after fully enjoying the fruits of his art, but for art history it is a success that can now be called imperishable, despite the fact that critics continue to be divided over Ligabue.

Ligabue’s greatness lies above all in his dimension as an authentic primitive, as an artist who paints without formalism but only because he is driven by an inner necessity that does not respond to any preconceptions or legacies derived from study or tradition: for Ligabue, art is an innate need. And his works are there to testify to that: so let us learn about his life, some of his masterpieces, the reasons for his greatness, and where to see his works.

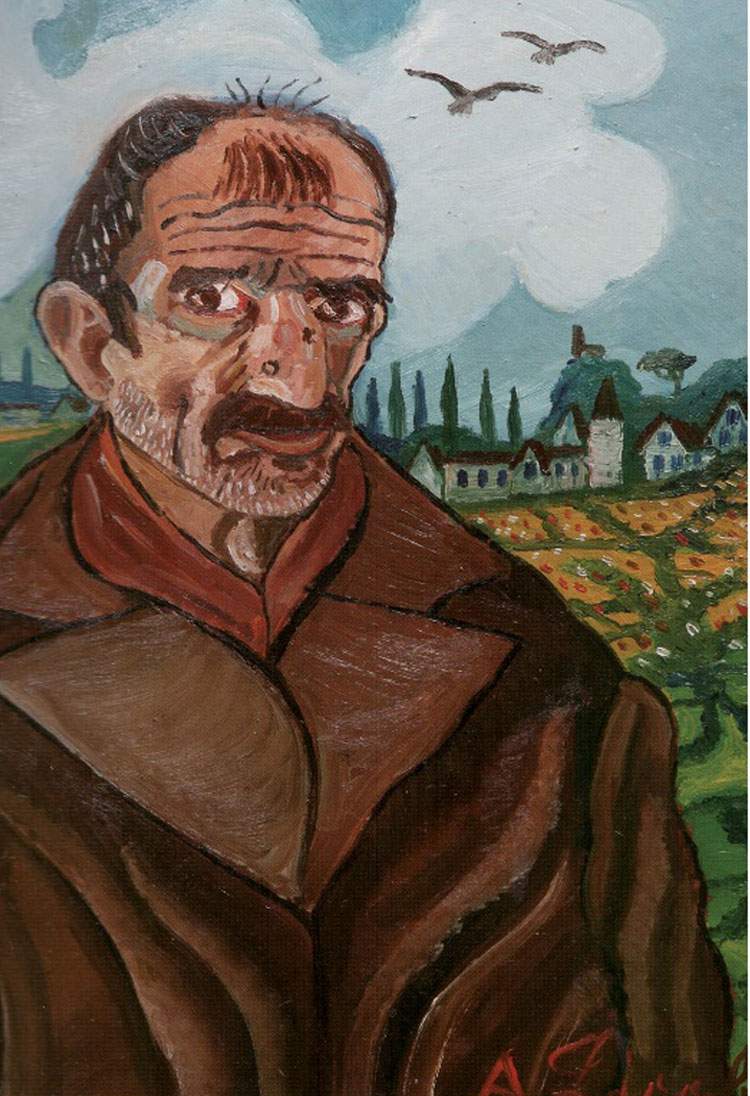

|

| Antonio Ligabue, Self-Portrait (1955-56; oil on faesite panel, 45 x 35 cm; Gualtieri, Fondazione Museo Antonio Ligabue) |

Ligabue: biography

Antonio Ligabue was born on December 18, 1899, in Zurich, Switzerland: his mother was Elisabetta Costa, an emigrant from the village of Cencenighe Agordino, near Belluno. It is not known who the father is, and at the registry office in the Swiss city the infant is registered as Antonio Costa. In September 1900 he was placed in the care of a local couple, Johannes Valentin Göbel and Elise Hanselmann, with whom he lived until 1919: the child (who did not speak Italian, but only German: he attended school until the third grade, in the town of Tablat, near St. Gallen), remained very attached to his adoptive family. Meanwhile, in 1901, an emigrant originally from Gualtieri, Bonfiglio Laccabue, had married Elisabetta Costa in the town of Amrisweil, and soon afterwards legitimized little Antonio by giving him his surname: the painter, however, would never love his stepfather, and the disdain would be such that later, having reached the age of majority, he would change his surname, transforming it, precisely, into “Ligabue.”

The artist, as an adolescent, manifested some psychiatric problems, so much so that in 1913 he was enrolled in a boarding school for boys with disabilities: Antonio, however, made up for his problems with his artistic talent, which was, however, neither recognized nor noticed, and also accomplice to his impatience with school, the artist, who had only the fourth grade at the age of fifteen, having finished his compulsory schooling began to support himself with odd jobs. In 1917 dates his first hospitalization in a psychiatric clinic, in Pfäfers, due to a violent outburst against Elise Hanselmann. He remained hospitalized for three months, but the problems were not over: his unruly life caused strong disagreements between him and his adoptive family, so much so that Elise later decided to denounce him, and on May 15, 1919, the boy was expelled from Switzerland. He is thus escorted just across the border, to Como: the prefect of the Lombard city arranges for him to be sent to Gualtieri, his stepfather’s town of origin, where he arrives escorted by the Carabinieri.

Life in Emilia is not easy for the artist: he does not speak Italian, lives in the countryside alone, is unable to integrate with the local population, has a temper easily prone to anger, continues to lead an unruly life, and even tries, in vain, to return to Switzerland (he is in fact stopped in Lodi, only to be taken back to Gualtieri). The artist lives on public subsidies, odd jobs found occasionally, charity and the little money he receives from his adoptive mother. However, Ligabue begins to paint and model small clay sculptures with clay collected from the Po River, and he begins to be noticed with his creations in the village: he gives them away in exchange for food or small services (for example, in exchange for a session at the barber), and the inhabitants, believing him to be a madman rather than an artist, accept them just for charity. It was in the winter of 1928-1929 that he first met Mazzacurati, who had just moved to Gualtieri (here he would live until 1937, setting up his studio in Villa Torello Malaspina). Ligabue’s life continued between ups and downs until 1937, when he suffered a new hospitalization, at the San Lazzaro psychiatric hospital in Reggio Emilia, because of his acts of self-harm and some of his violent outbursts. Here he spends half the year, from July until December: he will return to San Lazzaro for “manic-depressive psychosis” in March 1940. He would only get out in May 1941, after a year, thanks to the intercession of one of his closest friends, sculptor Andrea Mozzali, who hosted him at his home in Guastalla.

During the war, Ligabue, given his perfect knowledge of German, finds work as an interpreter, risking great trouble, however, because of a fierce altercation with a German soldier: he is saved from dire consequences only because he is considered insane and is therefore taken back to San Lazzaro. The hospitalization this time lasted three years: he got out in 1948 and began to exhibit in small local exhibitions, winning a few prizes, moreover. Thanks to Mazzacurati’s interest, he begins to tread increasingly important stages and earn money through art. By the 1950s, he has emerged from his destitute situation and, indeed, even manages to satisfy a few luxuries: for example, he begins to buy motorcycles, his real passion, and to drive around in a car complete with chauffeur. In February 1961 he exhibited for the first time in Rome, at “La Barcaccia” Gallery, and in June of the same year he ended up in the hospital because of a motorcycle accident. His success was short-lived because in November 1962, just days before the opening of a major anthological exhibition in Guastalla, he was struck by paresis and was hospitalized at the Carri hospital in Gualtieri, where he would remain for the rest of his days, while continuing to paint. He disappears here on May 27, 1965.

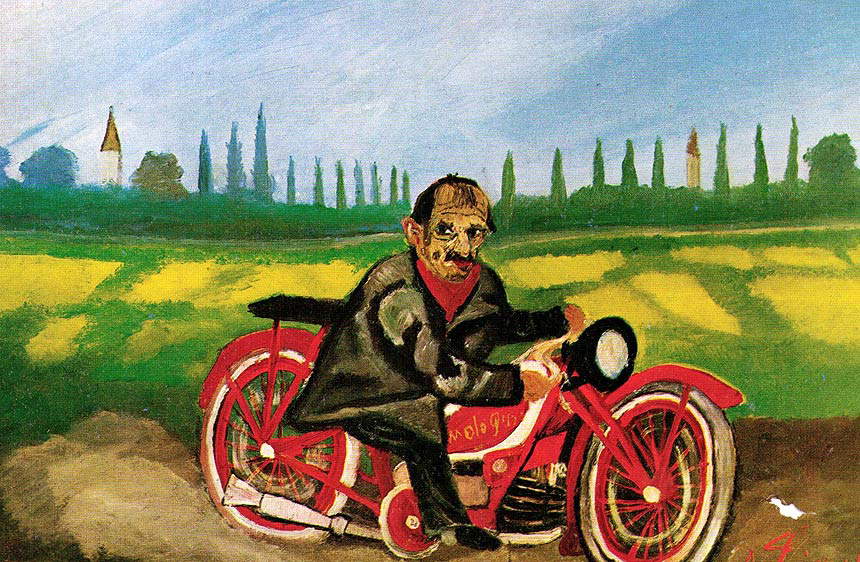

|

| Antonio Ligabue, Self-Portrait on Motorcycle (1953; oil on faesite 39 x 57 cm; Gualtieri, Antonio Ligabue Archive Foundation) |

Ligabue’s works

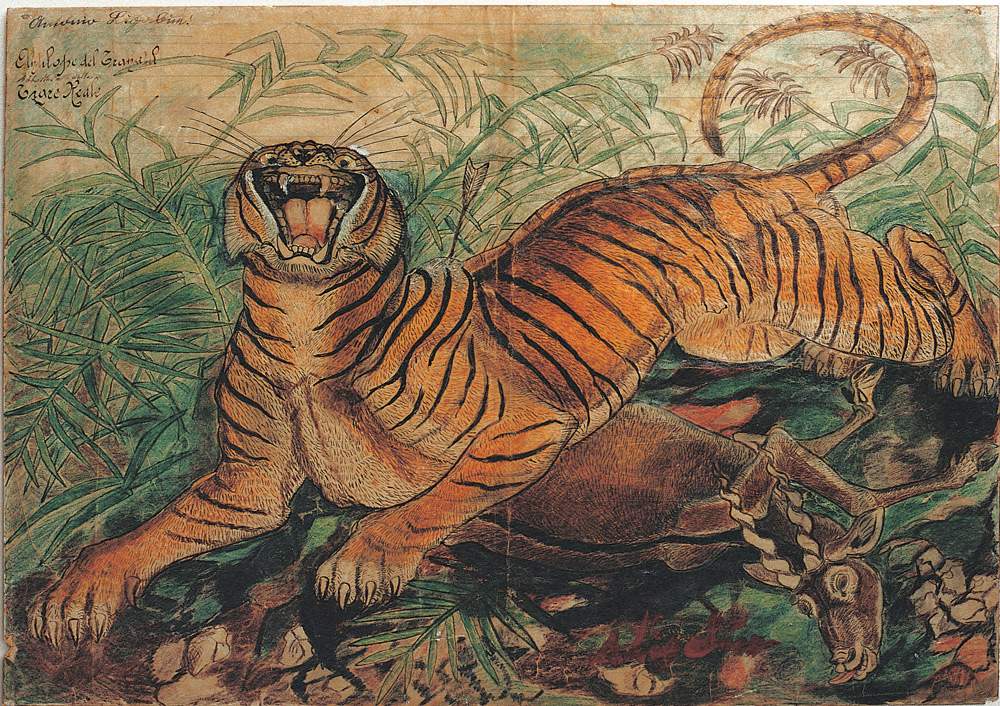

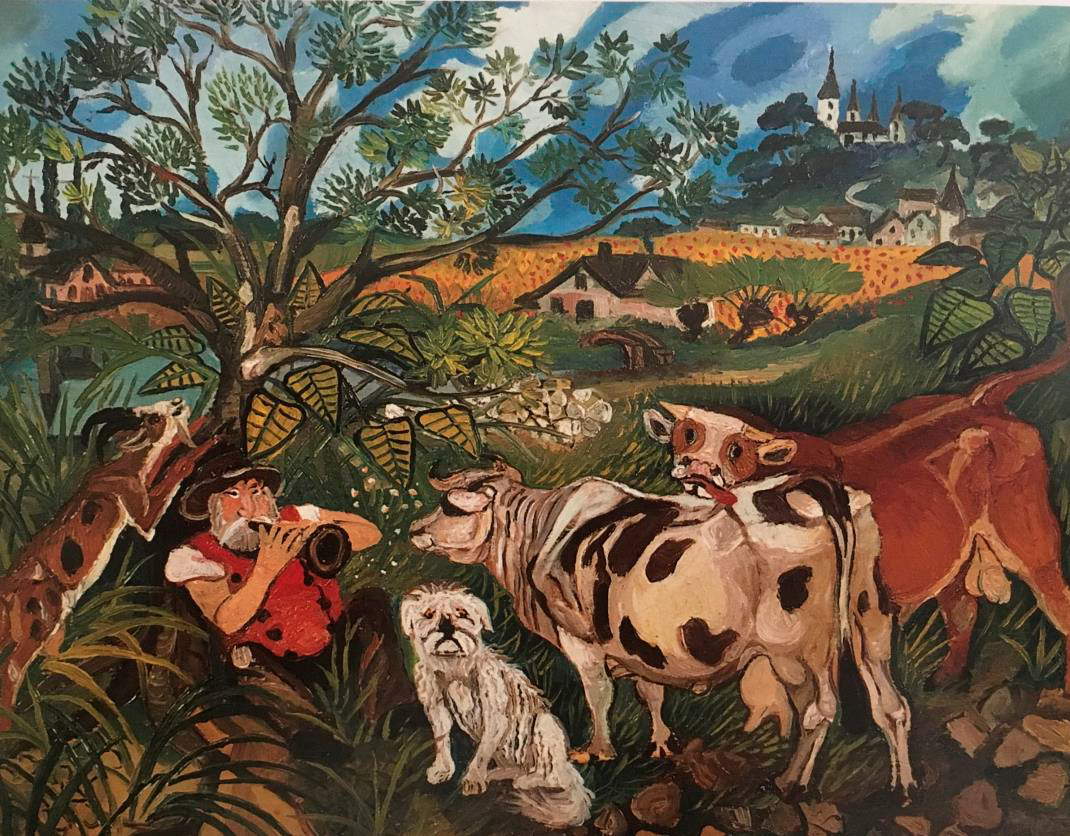

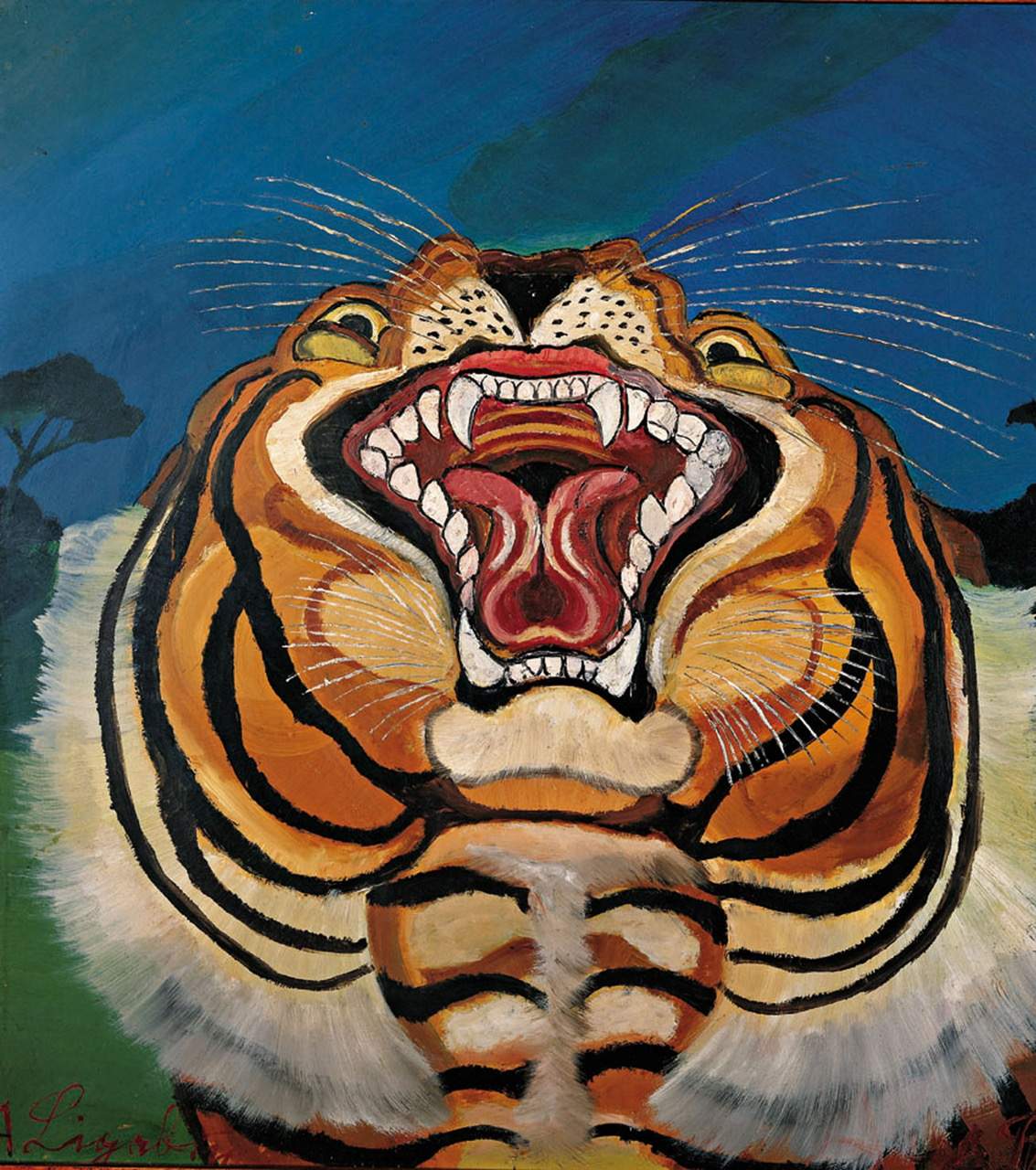

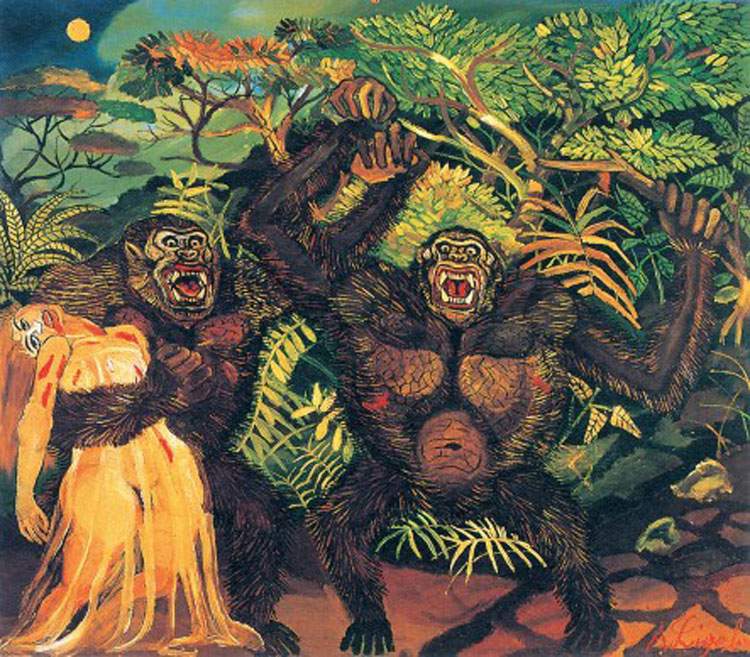

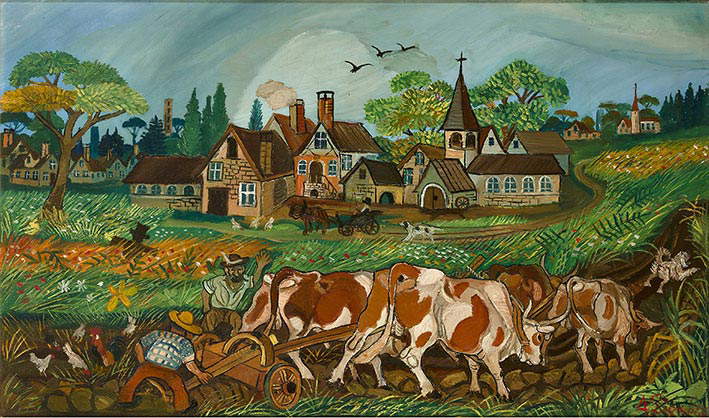

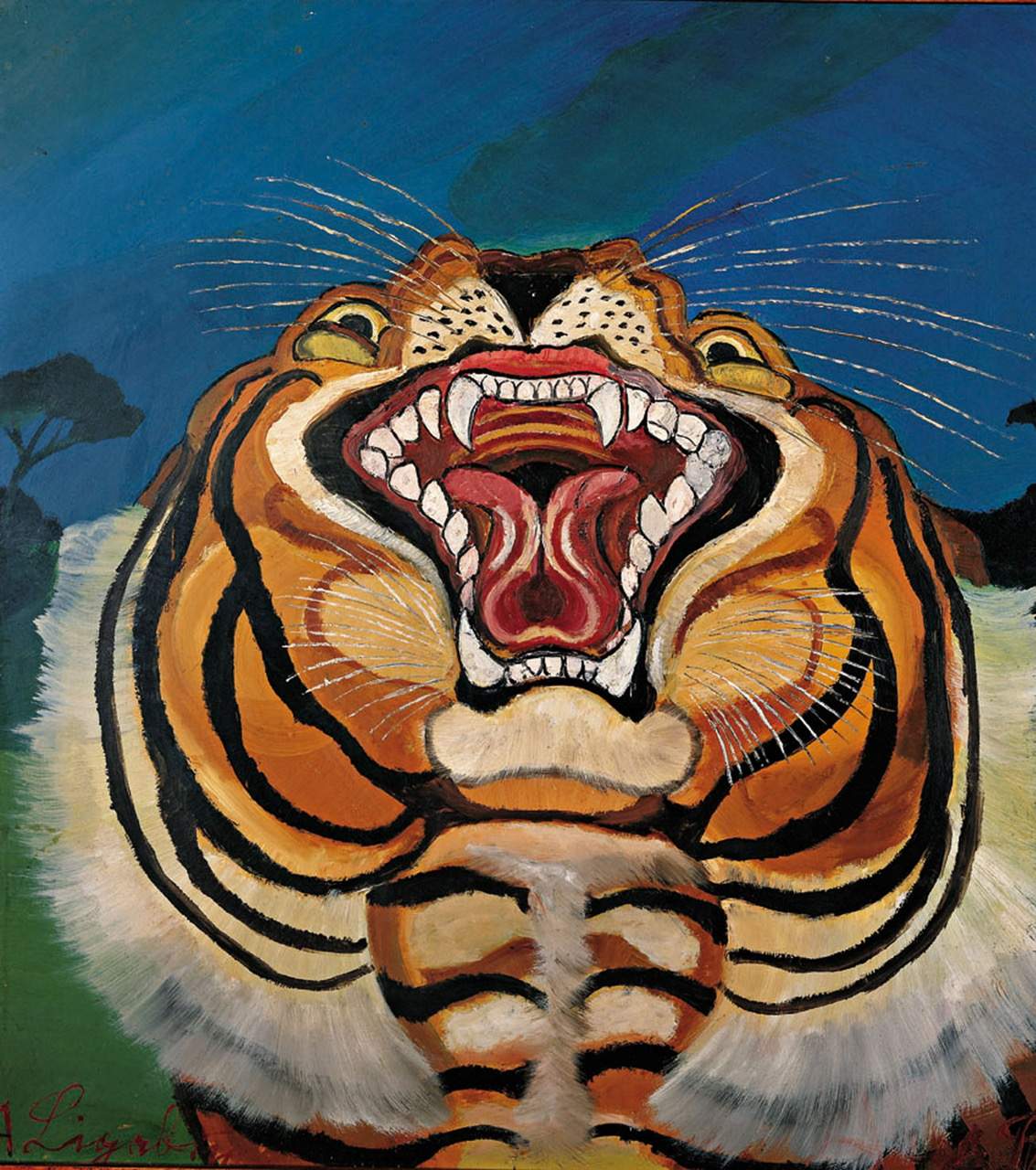

Ligabue’s work can be divided into three main periods, according to the most recent classifications made by critics. In the first period, which runs from 1927 to 1939, Ligabue’s paintings are the most “delicate” of his career: light colors, an impasto that is not too dense as it will be later, themes drawn mainly from the world of the countryside, with scenes of rural life. However, there is already no shortage of the ferocious animals that so fascinated him and that Ligabue painted by copying them from animal books (he never saw live many of the animals he fantasized about: tigers, huge spiders, gorillas, leopards, lions, large snakes), but the furious fights between beasts would appear later. The second period is from the beginning of World War I to the years of affirmation, roughly from 1939 to 1952: the subject matter becomes more full-bodied and dense and the works become more finished. The third period is the one in which the artist produced the most, and goes from 1952 to the year of his death: Ligabue’s painting becomes sharper, almost nervous, a further reflection of his state of mind. In the last years, moreover, the presence of his celebrated self-portraits abounds, which, on the other hand, are almost completely absent in the early stages of his career. It should be specified that many works from the early stages have been lost: these are those that the artist gave away or exchanged for modest consideration with the people of Gualtieri, who did not understand their importance and therefore also tended to throw them away.

There are several recurring themes in Ligabue’s works. For example, the self-portraits, through which the artist expresses his suffered condition and discomfort, a situation aggravated by his psychosis. Then there is the natural world and country life, which never abandon Antonio Ligabue’s art even in his last period (for example in Aratura, a 1961 work from the Ligabue Foundation in Gualtieri). And then there are the probably most iconic paintings of his production, those with ferocious beasts, with which the artist moreover identified, so much so that he took on their attitudes before painting them (he would stand in front of a mirror and imitate their cries and movements before setting to work). These animals express the artist’s desire for freedom and affirmation, but they are also a symbol of his enormous energy that manifested itself through art. A strength that Ligabue also expressed through the many scenes of animal fights that abound among both his paintings and sculptures.

Of the relationship with animals also spoke Mazzacurati himself, who witnessed firsthand an “encounter” between Ligabue and the beasts of a farm, a fact that was anything but unusual (Ligabue lived for a long time in the woods and had for a long time the sole company of the animals that lived along the Po: and he remained a wild man all his life). “He felt a very strong love for them,” Mazzacurati wrote in 1965, “and over all he exercised an extraordinary power. I remember that, later, when he settled on the farm near my house, it was enough for him to make strange gestures with his hands and arms and emit a slight hissing sound with his mouth, for all the animals, as if mad, to run around him. Dogs wagged their tails, cats meowed, pigeons swirled around his head, even chickens clucked near his feet: it was an incredible spectacle, mystical and arcane at the same time.”

|

| Antonio Ligabue, Leopard with Buffalo and Hyena (1928; oil on canvas, 83 x 126 cm; Gualtieri, Ligabue Archive Foundation) |

|

| Antonio Ligabue, Royal Tiger (1941; India ink and wax pastels on letterhead of San Lazzaro Psychiatric Hospital in Reggio Emilia, 36 x 50 cm; Reggio Emilia, private collection) |

|

| Antonio Ligabue, The Piper (1943-1945; oil on plywood, 40 x 56 cm; Gualtieri, Fondazione Museo Antonio Ligabue) |

|

| Antonio Ligabue, Head of a Tiger (1955-1956; oil on faesite, 75 x 64 cm; Gualtieri, Fondazione Museo Antonio Ligabue) |

|

| Antonio Ligabue, Fox on the Run (1952-1962; oil on faesite, 43 x 40.5 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Antonio Ligabue, Gorilla with Woman (1957-58; oil on faesite panel, 88 x 100 cm; private collection) |

|

| Antonio Ligabue, Self-Portrait (1955-56; oil on faesite panel, 45 x 35 cm; Gualtieri, Fondazione Museo Antonio Ligabue) |

|

| Antonio Ligabue, Plowing (1961; oil on canvas, 65.5 x 110 cm; Gualtieri, Antonio Ligabue Archive Foundation) |

Ligabue’s importance

In what does the importance and greatness of Ligabue’s art consist? There is first of all to premise that the opinion of critics on the Swiss-born artist are far from unanimous: and indeed the temptation to wonder how much Ligabue can be considered an “artist” still takes many people. However, one might think that the main value of Antonio Ligabue’s painting and sculpture lies in its authenticity: its lack of ties to any school or any tradition (if one excepts the sculpture “lessons” he received from Mazzacurati: there are, moreover, several bronze castings curated by third parties, since Ligabue often did not even bake clay, because he did not have the temperament to follow the entire process of creating a sculpture), combined with his innate talent, his sense of composition, his prolificacy, and the strength that the artist is able to express with his paintings and sculptures make him a case with few equals in the history of twentieth-century art. In the past, he has long been ascribed to the strand ofnaïve art, or “naïve” art: an expression that lately has tended to be set aside since it was used in the past more for fashion than for scientific intent (towards the end of the 1950s the so-called naïf artists literally exploded, dragged along by articles published in magazines and magazines with large print runs: many of them, Ligabue in the lead, were seen as artists very close to popular feeling, and for that reason their production began to be popularized, perhaps even beyond its due), and within the scope of which artists from the most disparate experiences were assimilated. Today it is, if anything, more correct to speak of outsider art or art brut, albeit with all the problems that these definitions entail. For example, an initial discrepancy between “outsider” and “naïve” might today be established on the basis of the artist’s awareness (“outsider” artists who are totally outside the system and disinterested, “naïve” those who know that a system exists and who, perhaps naively, aim to be recognized).

Ligabue, however, is not totally new: for example, in the early twentieth century, some critics(Ardengo Soffici above all) had expressed an interest in “that painting,” Soffici wrote, “which intelligent people say is stupid [...],” that is, that “naïve, candid and virginal” painting, the painting “of simple men, of the poor in spirit, of those who have never seen a professor’s mustache.” For critics, this was an essential quest, especially to know the innermost reasons that lead a human being to make art. Ligabue can be considered the quintessence of those outsiders who so fascinated Soffici and other leading critics. Moreover, Ligabue was probably the most prolificoutsider who was able to reach qualitatively higher results without ever having attended masters or other artists (other painters considered naïf instead attended schools or other authors).

As a result, in recent years, critics close to Ligabue have begun to carry out work to achieve full critical and scholarly recognition of the artist: Ligabue, after all, is still not part of the “official canon,” so to speak. And there are still very few major museums that preserve his works. Some entities, for example, the Ligabue Archive Foundation, the Antonio Ligabue Museum Foundation and the Ligabue House-Museum have long been doing careful and rigorous work to ensure an appropriate location for the artist: there are several exhibitions organized around Italy (often occasions to learn more about the artist, but very often not) with the intention of bringing the public closer to Antonio Ligabue.

Where to see the works of Antonio Ligabue

To get to know Antonio Ligabue, a stop in Gualtieri is a must: here you can visit the Ligabue Museum set up in the rooms of Palazzo Bentivoglio or the Ligabue House-Museum, which is housed in a building where the artist lived for some time, at the Caleffi family, which still owns the building. Also active in Gualtieri is the Ligabue Archive Foundation, which owns a good number of the artist’s works, which are often taken around for exhibitions.

Leaving Gualtieri, perhaps the most important nucleus of Ligabue’s works in a museum open to the public is at the Labirinto della Masone in Fontanellato, in the collection of Franco Maria Ricci. Other works by Ligabue can be found, for example, at the Museo Magi ’900 in Pieve di Cento, near Ferrara (one of the most important museums dedicated to the twentieth century that there are in Emilia-Romagna), at the Mallè Museum in Dronero (Cuneo), and at the Museo d’Arte Moderna “Rimoldi” in Cortina d’Ampezzo. A self-portrait by Ligabue is also kept in the Vasari Corridor self-portrait collection at the Uffizi Gallery. At present, there are no major museums of twentieth-century art that house works by Ligabue: in fact, critics are still very divided on his account and we are still a long way from full recognition of his figure.

|

| Antonio Ligabue: the painter, life, works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.