Alighiero Boetti, life, style and works of the exponent of Arte Povera

Alighiero Boetti (Turin, 1940 - Rome, 1994) was one of the main protagonists of theArte Povera groupand one of the most appreciated Italian artists of the second half of the twentieth century. He began to take his first steps in art in the 1960s, very young, after leaving his university studies and deciding to follow his own passions. He soon joined the Arte Povera movement, only to succeed in gaining major international recognition right at the height of the collective’s success.

Boetti was a very prolific conceptual artist who used a variety of techniques to make his works, some even very manual ones such as embroidery or collage. He also made multiple versions of the same subject, producing them in rather large numbers. Clear examples of this are the works related to postal services, which have been reproduced over and over again by the artist to reason precisely about the concept of continuous mechanical realization. The conceptuality underlying Boetti’s works seems not to follow a particular strand, but to arise from various ideological cues ranging from the reuse of unconventional materials to geopolitics, from the concept of duplication to self-reflection, from Arab culture to geometry.

Very important for Boetti’s biography and artistic development was a trip to Afghanistan, a country where the artist returned periodically for a long time until the political events that led to the occupation of the country in the late 1970s prevented him from returning. Numerous exhibitions, both in his lifetime and posthumously, have been dedicated to him in major museums around the world, and a very substantial group of his works is part of the permanent collection of MoMA - Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The Life of Alighiero Boetti

Alighiero Fabrizio Boetti, a descendant of a family of noble origins (he was in fact a count), was born in Turin on December 16, 1940. His father, Corrado Boetti, was a lawyer, while his mother, Adelina Marchisio, was a violinist who later became an embroiderer. One of his ancestors, who lived in the 18th century, was the Dominican monk Giambattista Boetti, who called himself “Prophet Mansur” and was a missionary particularly active in the Caucasian lands. Boetti studied the arts as a self-taught artist in the 1960s, after leaving the University of Economics and Business in Turin to pursue his passions, which included literature, music and art. In particular, Boetti appreciated Paul Klee and Nicolas De Staël, and it was following the latter’s inspiration that he began to try his hand at landscape oil paintings in his early twenties. Shortly thereafter he moved to Paris to study and practice printmaking, and in 1962 on a trip to Vallauris with the intention of buying ceramics to take to Italy and resell, he met Annemarie Sauzeau, who two years later became his wife.

An important year for Boetti’s artistic career was certainly 1967, in which he debuted with his first solo exhibition at the Christian Stein Gallery in Turin and joined the Arte Povera collective, participating with them in a series of exhibitions in important Italian cities, including Genoa, Turin and Milan. It was precisely between the 1960s and the 1970s that he reached the height of notoriety along with the other Arte Povera artists, and he also began to exhibit abroad. A great lover of travel, meanwhile Boetti almost by chance went to Afghanistan for the first time, in 1971. He was so deeply fascinated by the country that he stayed there for more than a month and returned regularly at least twice a year until 1979, when the country suffered the Soviet invasion and it became impossible to return. Afghanistan had become almost a second homeland for him, and he devoted several energies as well as several works to this territory. In Kabul he decided to start a creative textile workshop, conceptually similar to Andy Warhol’s Factory, involving some local young embroiderers. He also took over a hotel in the Sharanaw residential neighborhood, named One Hotel.

Interestingly, in 1974 he brought with him on one of his periodic sojourns in the country a young man named Francesco Clemente, who would later be part of the Transavanguardia group and work side by side with Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat. In the fall of 1972 Boetti settled in Rome and began signing his works as “Alighiero e Boetti,” creating a kind of symbolic separation between his personality in private life, identified by his first name, and his personality in public life, represented by his last name. Subsequently, he participated in the XXXVI Venice Biennale and achieved several successes in New York, participating in John Weber’s “De Europa” exhibition and inaugurating his first solo exhibitions, held in 1973 at the Weber Gallery and in 1974 at the Sperone Gallery. He moved to the city for a long period and exhibited again at the Weber Gallery. International recognition continued in 1978 with a major anthological exhibition dedicated to him at the Kunsthalle Basel.

On his fortieth birthday in 1980, Boetti began a stable collaboration with the newspaper “Il manifesto,” producing a drawing a day published in the paper for about five months. In the 1980s he continued his intense exhibition activity all over the world, starting with his participation in the exhibition “Identité italienne - L’art en Italie depuis 1959” in the famous Pompidou Center in Paris curated by critic Germano Celant, continuing with his participation in other important exhibitions, “Documenta” in Kassel in 1982, the solo show “Ammazzare il Tempo” organized by Franz Paludetto in Turin in 1981, and Achille Bonito Oliva’s group show “Avanguardia transavanguardia” at the Aurelian Walls in Rome in 1982.

The years of major international exhibitions coincided, however, with some unpleasant episodes on a personal level, as Boetti’s health, already compromised due to unhealthy habits in the 1970s, deteriorated following a car accident in the Cinque Terre that led to after-effects for several months. In addition, he separated from his wife Annemarie. Between 1985 and 1986 he set up a new studio near the Pantheon, also in Rome. He continued to exhibit his works very frequently around the world, until he was diagnosed with cancer in 1993. He died on April 24, 1994, at his home in Rome. Several posthumous exhibitions were dedicated to the artist’s memory, especially in the United States.

Alighiero Boetti’s style and major works

Alighiero Boetti’s production is decidedly multifaceted, both in the techniques he uses, which range from drawing, reuse, painting, three-dimensionality to embroidery, and in the themes he deals with, which basically belong to the conceptual, ideological and philosophical sphere but do not focus on a particular strand, dealing with sometimes very different topics.

Boetti’s earliest works date from the 1960s, and they were drawings executed on paper with Indian ink that reproduced some recording equipment, such as microphones, movie cameras and cameras. In addition, fully adhering to the dictates of Arte Povera, he experimented with a range of different materials such as plaster, plexiglass, luminous devices and even eternit, with the intention of taking everyday objects and materials and making them into an art form. Following this concept, he gave birth to three-dimensional works such as Catasta (a series of eternit tubes arranged one on top of the other), Chair and Ladder (made entirely of wood), Ping Pong (two glass and wood squares with electronic devices that alternately illuminated the word “ping” and the word “pong”) and Annual Lamp (a lamp that lights once a year for 11 seconds at an unspecified time, thus celebrating not the event itself but the very idea of lighting), all dated to 1966.

Soon after, he made Manifesto 1967, in the same year as the title, a print that is deliberately hermetic and not easy to interpret. The peculiarity of the work, in addition to presenting symbols whose meaning has never been revealed, is inherent in the fact that it presents a list of names of artists close to Boetti, thus returning a snapshot of a generation of artists and specifically of the Arte Povera movement. Dating instead from 1968 is a particular postcard that Boetti had sent to about fifty friends, titled Gemini, where the front shows the artist holding an image of himself by the hand, an effect achieved through photomontage, while the back has several ironic phrases written on it, such as “De-singiamoci su.”

Soon after, he made a number of works on the theme of reflection and contemplation, including Niente da vedere, niente da nascondere (1969), a stained-glass window leaning against the wall that invites precisely contemplation, and the series Cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione (1969), a hybrid of opera and happening in which Boetti had reproduced squares of classic notebook sheets with a pencil on a canvas, replicating the work 25 times. He also recorded the sounds produced as he made each piece and timed the duration, in fact the first work in the series is titled 42 Hours.

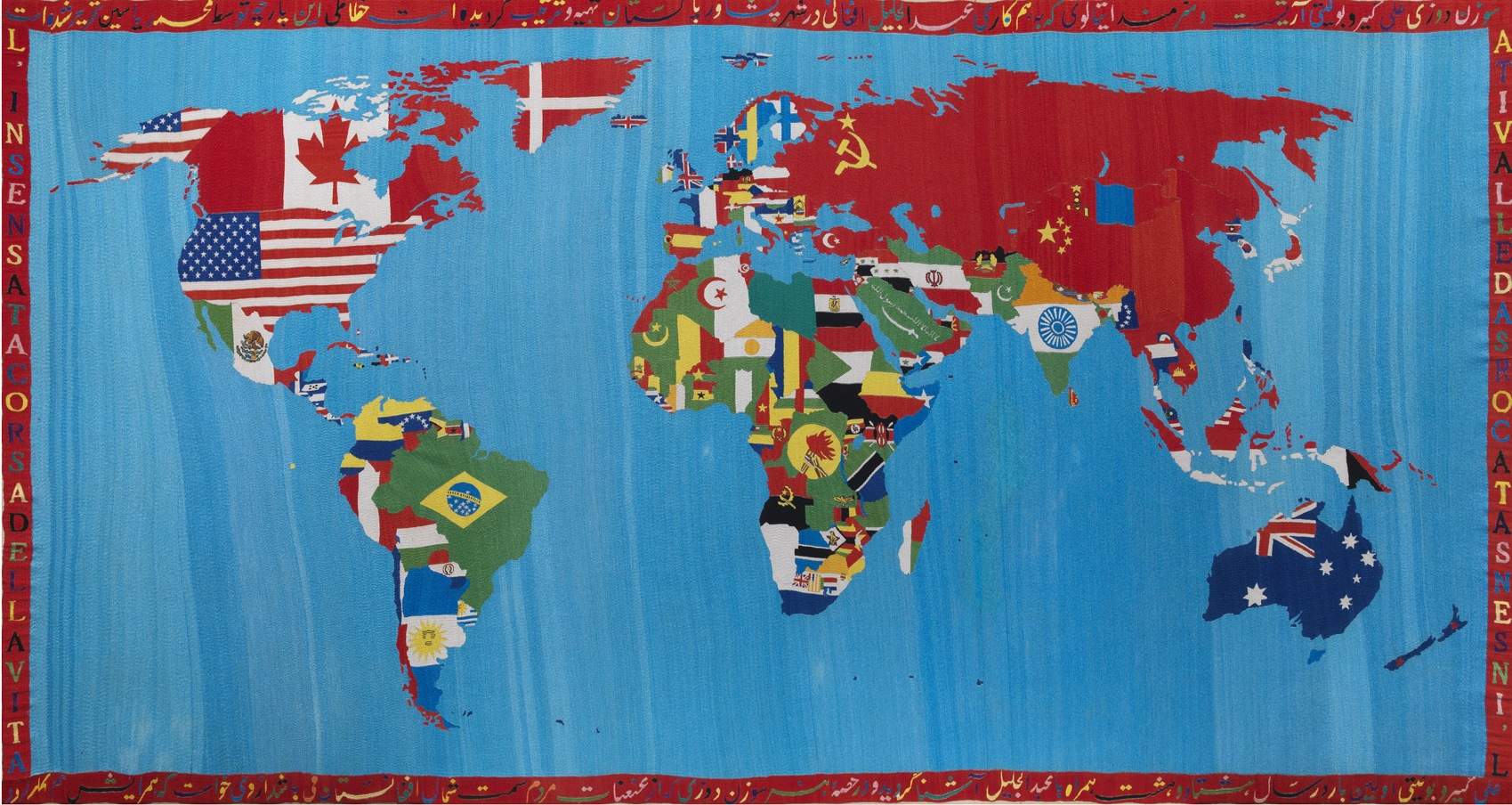

Boetti had a great interest in geopolitics, a subject he addressed in several works, especially in Maps, which happens to be among the artist’s best-known works. It is a reproduction of a planisphere, on which the territories of the various countries are not defined with the colors corresponding to the morphology of the terrain, as happens in real maps, but with their flags, thus reasoning about the sense of nationality. The first Map dates back to 1968 and was made on paper, while in 1971 Boetti produced a new embroidered version, during his stays in Afghanistan. Over the years he would make many more, now located in various museums around the world. The artist also added to each work an embroidered text in color consisting of his signature, the date, the place where it was made, plus there could sometimes be a dedication in Italian, Persian or Afghan. Still in the geopolitical sphere, in 1970 he devoted himself to the enterprise of cataloging the world’s rivers by length, also involving his wife Annemarie in the project, which was to become seven years later an artist’s book entitled Classifying the World’s One Thousand Longest Rivers (1977), published in 500 copies.

In 1970 he produced another series entitled Postal Journeys, in which he re-used letter envelopes to apply stamps of different colors and sizes to them as if they were for all intents and purposes colors on canvas, proposing numerous combinations. Beginning in 1973 Boetti greatly increased the volume of his production, never slowing down until the end. He often entrusted the practical realization of the works to other people as well, providing them with the sketch of his idea. An example is Piccolo, medio, grande from 1974, one of the works the artist made with the hatching technique by having two assistants help him, asking them to be a man and a woman. The assistants were tasked with coloring three panels of paper entirely using ballpoint pens, in this case black (but in other works based on the same approach the use of blue, green and red ink pens, i.e., commercially available colors, has been recognized). The alphabet, on the left side, and commas remain visible, and upon closer inspection of the work it becomes clear that the position of the commas is not random, but corresponds to one of the letters of the alphabet, and by reading them in sequence these reveal a message that is none other than the title of the work itself.

Several works that recur over the years, as early as the 1970s through the 1990s, are based on geometric and mathematical criteria, especially in the composition of the work itself. These works include Autodisporsi (1975), whose base is made up of the checkered sheets that Boetti had already used in the late 1960s, on which he draws geometric motifs; Da uno a dieci (1980), in which six squares enclose numerous smaller squares again with colorful geometric decorations, plus the addition of hands pointing with their fingers to the number of the corresponding square. Finally, geometries return in the embroidery Alternando da uno a cento e viceversa (1993), in which a black and white grid is surrounded by multicolored frames in which lines and arrows can be recognized.

The works dated to the first half of the 1980s turn out to be full of inscriptions made by Boetti with his left hand, recalling Arabic and Oriental calligraphy. In addition to calligraphy, the artist’s own hands often recur in the works of these years, seen from above and often interspersed with vertical marks. One of these is Per l’amor del cielo (For the Love of Heaven ) from 1986, in which the image of the artist (in addition to his hands, the head is recognizable) holding a pencil in his hands is replicated both at the top and bottom of the canvas, interspersed with vivid splashes of color expanding in the center, as a reference to the continuous flow of life. Also in the same vein is a work housed in the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Attracted by Sudden Center (1987), which takes up the same composition as Per l’amor del cielo but features more structured and articulated elements in the center. Meanwhile, Boetti’s embroidery work also continues with the help of Afghan women refugees in Peshawar, Pakistan. Up-to-date Maps , checkerboards with colored letters, and the large tapestries entitled Tutto, in which the fabric is completely filled with silhouettes of different colors and shapes, are made. In 1984 he presented the project Covers, or pencil tracings of the covers of the world’s leading news magazines. Boetti’s last works are the Extra strong series , produced with mixed techniques including colored ink, timbraure and collage on sheets of plain fax paper.

Where to see the works of Alighiero Boetti

Near Boetti’s hometown of Turin, and more specifically in the prestigious Rivoli Castle museum, it is possible to see a substantial group of his works consisting of Catasta (1966), Mancorrente m.2 (1966), Scala (1966), Sedia (1966), 8.50 (Zig Zag) (1966), La Bertesca (1967), Galleria dell’Ariete (1977), Tutto (1987). Staying in northern Italy, at MART - Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Rovereto and Trento, there is the work Per l’amor del cielo (1986), while at the Fondazione Prada in Milan there is Mimetico (1967). Two works, Ordine e disordine (1973), Non parto non resto (1984), are kept at MAMBo - Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. In 1977 Boetti decided to donate to CSAC - Centro Studi e Archivio della Comunicazione of the University of Parma the work Piccolo, medio, grande (1974), which can still be visited there. Other important works are at the Casamonti Collection in Florence.

Leaving Italy, it is possible to find Boetti’s works in Switzerland, such as the embroidery on canvas OGGI UNDICESIMO GIORNO SESTO MESE ANNO MILLENOVECENTOOTTANTANOVE (1989) at the Ghisla Foundation in Locarno, while in the Migros Museum of Contemporary Art in Zurich there is a Map (1983), and several works all made in 1986, namely four collages, two from the series Esercizi (Newsweek and Time Magazine) and two others respectively entitled Nella Limpida Chiara and Sentieri/Pensieri, finally two variations of Order and Disorder.

Five works are preserved in Paris at the famous Centre Pompidou: Untitled (Toward the South the Last of the Inhabited Countries is Arabia) (1968), What Always Speaks Silently is the Body (1974), Attracted by Sudden Center (1987) and another version of Everything (1987).

Finally, a large number of works can be found in the MoMA - Museum of Modern Art in New York, the most famous of which are, in chronological order: Postal Travels (1969-70), Manifesto (1967), Postal Dossier (1969-70), Two Hands and a Pencil (HEARING BETWEEN WORDS) (1977) and an alternative version of Map (1989).

|

| Alighiero Boetti, life, style and works of the exponent of Arte Povera |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.